In 2005, someone who posed as an Iraqi insurgent group posted online a photograph of a captured US soldier named John Adam. They threatened to behead him if prisoners being held in US jails in Iraq were not freed. The US military took the claim seriously but couldn’t locate a John Adam within their ranks. It eventually emerged that John Adam was Special Ops Cody: a souvenir action figure of both African American and Caucasian likenesses. The dolls were available for sale exclusively on US bases in Kuwait and Iraq, and were often sent home to soldiers’ children as a surrogate for a deployed parent.

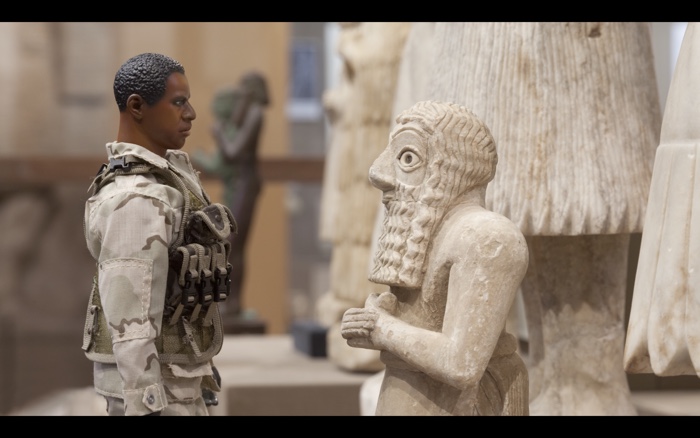

Michael Rakowitz, The Ballad of Special Ops Cody, 2017. Film still. Courtesy the artist and Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Torino

Michael Rakowitz, The Ballad of Special Ops Cody, 2017. Excerpt

In Michael Rakowitz’ stop-motion film The Ballad of Special Ops Cody, an action figure breaks into a vitrine at the Oriental Institute in Chicago in order to meet small votive statues from Mesopotamia. It is Special Ops Cody, the toy soldier associated to the Iraqi hoax.

Ancient votive statues have something in common with the action figure: they were surrogates too. Commissioned by the Mesopotamian elite as images of themselves to embody them in religious contexts, they allowed the person they represented to have a spiritual presence when their physical body was away.

In the video, Cody urges the statues to go back to their homes. The artworks, however, remain petrified and silent.

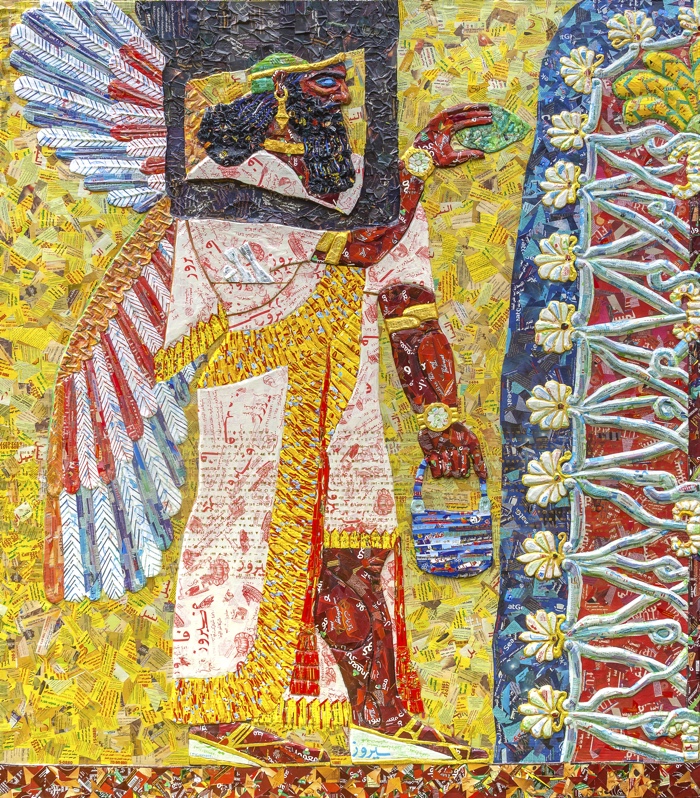

Michael Rakowitz, The invisible enemy should not exist, 2007-ongoing

Michael Rakowitz, The invisible enemy should not exist (detail), 2007-ongoing

Michael Rakowitz, paraSITE, 1997-ongoing. Shelter for George L., Cambridge, 1998. Photo Michael Rakowitz

The film is part of Michael Rakowitz. Imperfect Binding at the Castello di Rivoli Museum of Contemporary Art near Turin, Italy. The exhibition is conceived as a survey of the artist’s over-twenty-year practice traversing architecture, archeology, cooking practice and geopolitics from ancient times to nowadays. I’ve been a fan of Rakowitz since i discovered the inflatable shelters he designed for and together with homeless people some 20 years ago. He hasn’t done anything remotely dull, uninspiring or dispassionate ever since. His work is inhabited by ghosts, invisible and invisibilised communities, generosity and his own heritage as the grandson of Iraqi-Jews who were forced to emigrate from Baghdad to the U.S. in the mid-20th century.

Michael Rakowitz, The invisible enemy should not exist, 2007-ongoing. Photo Andy Keate

Michael Rakowitz, The invisible enemy should not exist (detail), 2007-ongoing

Michael Rakowitz, The invisible enemy should not exist (detail), 2007-ongoing

One of the most spectacular works in the exhibition is The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist. The series attempts to reconstruct the thousands of archeological artifacts looted from the National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad, in the aftermath of the US invasion of April 2003, and the continued destruction of Mesopotamian cultural heritage by groups such as ISIS. The pillage and the destructions horrified everyone. In Iraq, in the U.S. and in the rest of the world, people felt like a vital part of the world cultural heritage had just been violated. Suddenly, it didn’t matter whether you were for or against the war. The indignation, however, didn’t extend to the local populations who had lost their livelihood, family or even their lives during or after the U.S. invasion of the country.

In Rivoli, long tables are covered with sculptural replicas of artifacts stolen from sites in Iraq and Syria. Rakowitz and his team have spent the past 13 years gathering information about the missing objects from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago’s database and the Interpol website. All of the stolen objects are then handmade in the artist’ studio using the packaging of food products produced in northern Iraq -in particular date cakes (maamoul) and date syrup- as well as from Arabic newspapers found in cities across the United States and Europe, places where Iraqis have sought refuge from the conflicts that continues to plague their country.

A general amnesty was declared for anyone willing to return stolen objects. About half of the 15 000 objects were recovered. Small objects came first, mostly brought in by locals who apologised, saying they had taken them for safekeeping. Even copies of objects for sale in the museum gift shop were returned. There is still a long way to go for Rakowitz and his team though. Since they started the reproduction endeavour in 2007, they have reconstructed “only” 700 artifacts.

Michael Rakowitz, The invisible enemy should not exist (Room N, Northwest Palace of Nimrud), 2018. Photo Robert Chase Heishman

Michael Rakowitz. Installation view at Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea. Photo Antonio Maniscalco. Courtesy Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Turin

In an interview with Malmö Konsthall, Rakowitz gives a moving outline of his background and the motivations behind the colossal quest of faithfully replicating lost artifacts:

Michael Rakowitz at Malmö Konsthall

The title of this body of work, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, is the direct translation of Aj-ibur-shapu – the ancient processional way that ran through the Ishtar Gate, the eighth gate to the inner city of Babylon. The gigantic and colourful brick gate was constructed in about 575 BCE by order of King Nebuchadnezzar II.

Rakowitz used the same papier maché technique he had deployed to replicate the small artifacts to reconstruct some of the large stone reliefs that used to adorn the Northwest Palace built by Neo-Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) in the ancient city of Nimrud located on the Tigris River in northern Iraq. Prior to its demolition by members of the so-called Islamic State in 2015, the palace’s many rooms were all decorated with 2m 30cm high limestone reliefs depicting figures and ornamental flowers.

The reconstructed reliefs adopt the colour schemes believed by archaeologists to have been painted on the limestone when the panels were carved in the 9th century BC.

Just like the toy soldier and the ancient votive statues above, the replicas serve as stand-ins for priceless objects lost in a tragedy of cultural pillage that started long before 2003 with Western archaeologists deciding that these ancient artifacts were so valuable they ought to be shipped to Western countries where they were added to the collection of museums.

Michael Rakowitz, The invisible enemy should not exist (Lamassu), 2018. Trafalgar Square, London, 2018. Photo Gautier DeBlonde

The invisible enemy should not exist made a spectacular entrance into public space in March 2018 when a reconstruction of the Lamassu destroyed by ISIS in Nineveh, was installed on the Fourth Plinth in London’s Trafalgar Square. The human-headed winged bull is made from 10,500 empty Iraqi date syrup cans. This references another dimension of Iraqi loss. Aside from the destruction of historic sites begun by the US-led bombardment, invasion and occupation, the country is now also deprived of one of its leading industries and traditions: the production of dates which greatly suffered from the military attacks and the trade embargo.

Michael Rakowitz. Legatura imperfetta/Imperfect Binding is a captivating invitation to reflect on diaspora, war trauma and violence, dispossession, globalization and objects that are welcome to enter a country while humans are not. Only Rakowitz could make such heavy topics both heart-breaking and joyful.

More images from the exhibition:

Michael Rakowitz, Dull Roar, 2005. Installation view at Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea. Photo Antonio Maniscalco. Courtesy Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Turin

Michael Rakowitz. Installation view at Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea. Photo Antonio Maniscalco. Courtesy Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Turin

Michael Rakowitz. Installation view at Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea. Photo Antonio Maniscalco. Courtesy Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Turin

I wish i could have found the audio of what became the soundtrack of the exhibition for me: Smoke On The Water. Not the famous Deep Purple version, but a cover by New York-based Arabic band Ayyoub. It still talks about absurd violence but the Arabic instrumentation makes it more dancey and haunting.

Michael Rakowitz. Legatura imperfetta/Imperfect Binding was curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Iwona Blazwick and Marianna Vecellio. The exhibition remains on view at Castello di Rivoli Museum of Contemporary Art near Turin until 19 January 2020.

Previously: The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own, Michael Rakowitz’ Dull Roar at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven (NL), Enemy Kitchen, paraSITE shelters, etc.