My first stop in Tokyo, once i had dropped my suitcase at the hotel was for the Mori Art Museum. The Roppongi art space has opened Medicine and Art, an exhibition which, despite its grandiloquent sub-title “Imagining the Future for Art and Love”, was every bit as brilliant as i had hoped.

Prosthetics, anatomical drawings by Michelangelo, an ornate amputation saw from ca. 1650, disturbing prints by Patricia Piccinini, diagrams by René Descartes, Tibetan anatomical figures, a painting by Damien Hirst, etc. Some 150 medical artifacts from the Wellcome Collection in London and works of old Japanese and contemporary art are exhibited side by side. Without any hierarchy nor anxiety. Each and everyone of them offers the most seducing spectacle about life.

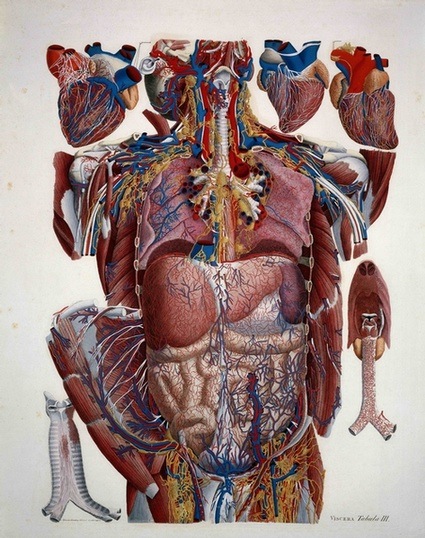

Paolo Mascagni, Anatomical Illustration. Credit: Wellcome Library, London

Paolo Mascagni, Anatomical Illustration. Credit: Wellcome Library, London

From ancient times humans have sought to unravel the secret mechanisms of the body, developing in the process a wealth of medical expertise. At the same time we have seen our own bodies as vessels for the representation of ideals of beauty, and long sought to depict our bodies in paintings and drawings.

The exhibition is bold, provoking and it has the merit of bringing together oriental medicine and our own western idea of the art and science of healing.

The first part of the exhibition is all about Discovering the Inner World of the Body: How did people around the world first acquire understanding of the mechanisms of the human body and the vast world it contains? The first section of the exhibition answers that question by tracing various scientific developments through a vast array of artefacts. One of the highlights of the show is a series of drawings by Leonardo da Vinci. For the Renaissance man, understanding the human body was a first step towards uncovering the mysteries of the outside world. Besides, his work epitomizes the spirit of the Tokyo exhibition. Da Vinci, better than anyone, managed to combine a scientific and an artistic approach to the study of the human body.

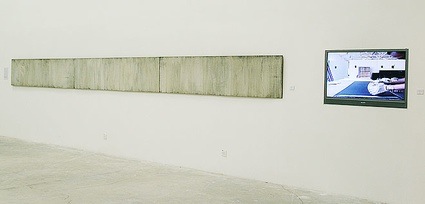

Exhibition view (image Mori Art Museum) featuring Bal Yiluo, Recycling, 2009

Exhibition view (image Mori Art Museum) featuring Bal Yiluo, Recycling, 2009

Iron model of the joints in a human skeleton, Italy, 1570-1700. Credit: Science Museum, London

Iron model of the joints in a human skeleton, Italy, 1570-1700. Credit: Science Museum, London

This 30-cm tall, fully articulated iron manikin is thought to have been used at mediacal schools during the 16th and 17th centuries for demonstrating the structure of joints and for teaching joint-related how to treat joint-related diseases.

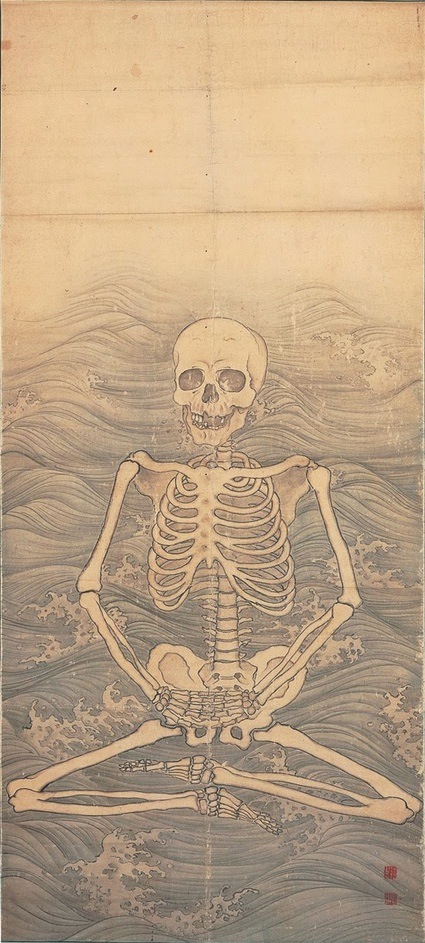

Maruyama Okyo, Skeleton Performing Zazen on Waves, c.1787 (Daijoji Temple, Hyogo, Japan)

Maruyama Okyo, Skeleton Performing Zazen on Waves, c.1787 (Daijoji Temple, Hyogo, Japan)

The second section, Fighting Against Death and Disease covers the way people have tried to fight against death and disease through the ages. In addition to presenting the history of medicine, pharmaceuticals, artificial limbs and organs, life sciences and scientific technology, this section poses philosophical questions about the nature of life and death with the various memento mori works.

Alvin Zafra, Argument from Nowhere, 2000

Alvin Zafra, Argument from Nowhere, 2000

One of the most striking pieces in the show is Alvin Zafra‘s ‘Argument from Nowhere’. It doesn’t look like anything else but an abstract painting. Until you read the notice and see the video of how the artwork came to life. Zafra vigorously grounded a human skull to powder against a seven-meter long panel of sandpaper, leaving a soft gradient of grey monotones. The operation took 14 days. Zafra said his motivation was “to paint a beautiful image of death.”

Tetsuya NOGUCHI, “Target Marks 1580” and “Target Marks 1610”, 2009

Tetsuya NOGUCHI, “Target Marks 1580” and “Target Marks 1610”, 2009

Tetsuya Noguchi crafted two figures. The first one represents a young warrior wearing armor in the style of the Warring States period, the second sculpture represents the same man, only he is thirty years older and lives therefore in the Azuchi-Momoyama period.

The armour worn by the figures is ambivalent. Made to protect the body and relieve warriors’s fear of death and misery, this armour also features several targets that invites death or injury to the body.

Ernst Pohl, Omniskop X-ray apparatus, 1910. Science Museum, London

Ernst Pohl, Omniskop X-ray apparatus, 1910. Science Museum, London

In the early 1920’s, Ernst Pohl created the ground-breaking Omniscope. This X-ray machine could be rotated completely around the patient which greatly enhanced the diagnostic and therapeutic potential. By the end of World War II, around 400 units had been manufactured and delivered throughout Europe, the USA, Japan and the Soviet Union (via.)

Set of fifty artificial eyes, Liverpool, England, 1900-1940

Set of fifty artificial eyes, Liverpool, England, 1900-1940

Damien Hirst, Surgical Procedure (Maia), 2007

Damien Hirst, Surgical Procedure (Maia), 2007

Kamata Keishu, Surgery for Breast Cancer, 1851. Credit: Wellcome Library, London

Kamata Keishu, Surgery for Breast Cancer, 1851. Credit: Wellcome Library, London

In 1851, Kamata Keishu compiled a ten-volume medical treatise called Geka kihai in which he described and illustrated the surgical techniques pioneered by his teacher, surgeon, Hanaoka Seishu. The illustration above shows the excision of a cancerous growth from a woman’s breast, an operation which Hanaoka Seishu first carried out in 1804 using general anesthetic.

Custom built iron lung, Cardiff, Wales, 1941-1950

Custom built iron lung, Cardiff, Wales, 1941-1950

The picture above shows the ancestor of respiratory nasal masks. The patient with respiratory problems was encased in the wooden box up to their neck. The air pressure inside the box was alternated by operating the giant leather bellows. This caused the lungs to inflate and deflate so the person could breathe. During black outs or period of unstable electrical power supply, nurses were said o have operated it by pushing the bellows with their hands.

To be continued…

The exhibition Medicine and Art runs until February 28, 2010 at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo.