Google Ads (formerly AdWords) is an advertising platform that allows businesses to bid on the keywords they are interested in. The higher your bid, the more prominent your clickable ad on the search engine results.

In poetry and other forms of literature, words acquire value based on the type of emotions, mental landscapes and history they evoke. For Google algorithm however, the value of a word fluctuates according to the power of the industry that uses and advertises it. The term “cloud”, for example, evokes meditative moments, dreams and celestial visions. But on Google planet, it is associated to the technology that uses the internet and remote servers to store data and applications. Which explains why the word “cloud” is much more expensive than the word “sunny” for example. This type of emotionless commodification of language has helped Google become one the most successful and wealthy companies in the world.

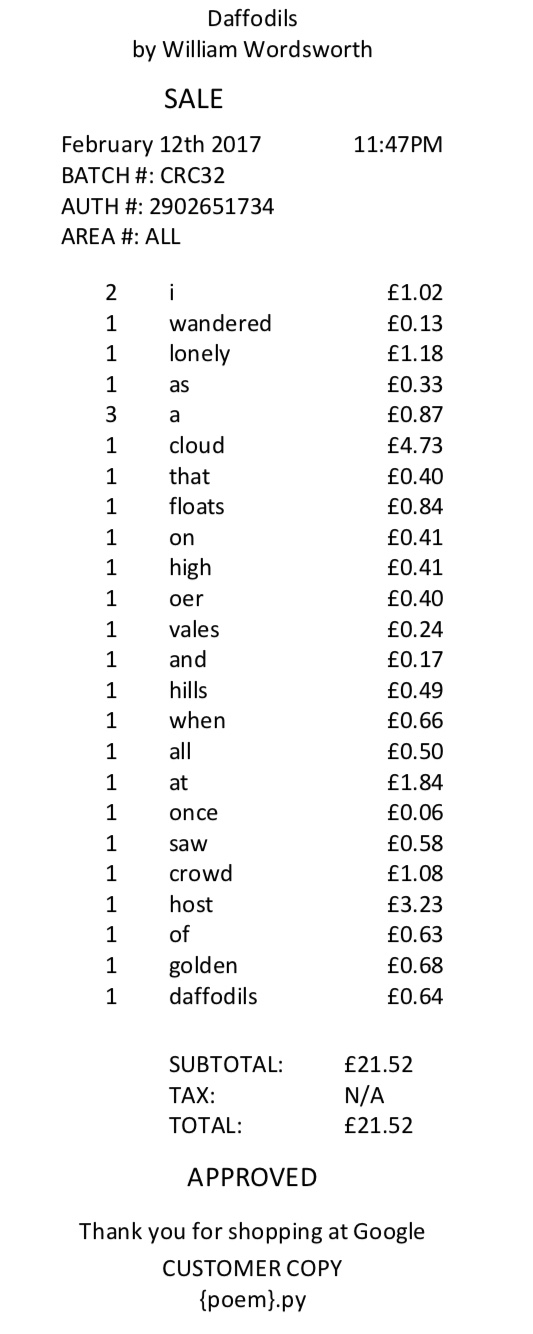

Pip Thornton, William Wordsworth’s Daffodils, 2019. Photo credit: Chris Scott

Dr Pip Thornton‘s research explores the economic, cultural and political effects of this monetisation of language.

As the value of words shifts from conveyor of meaning to conveyor of capital, she writes, has Google become an all powerful usurer of language, and if so, how long before the linguistic bubble bursts?

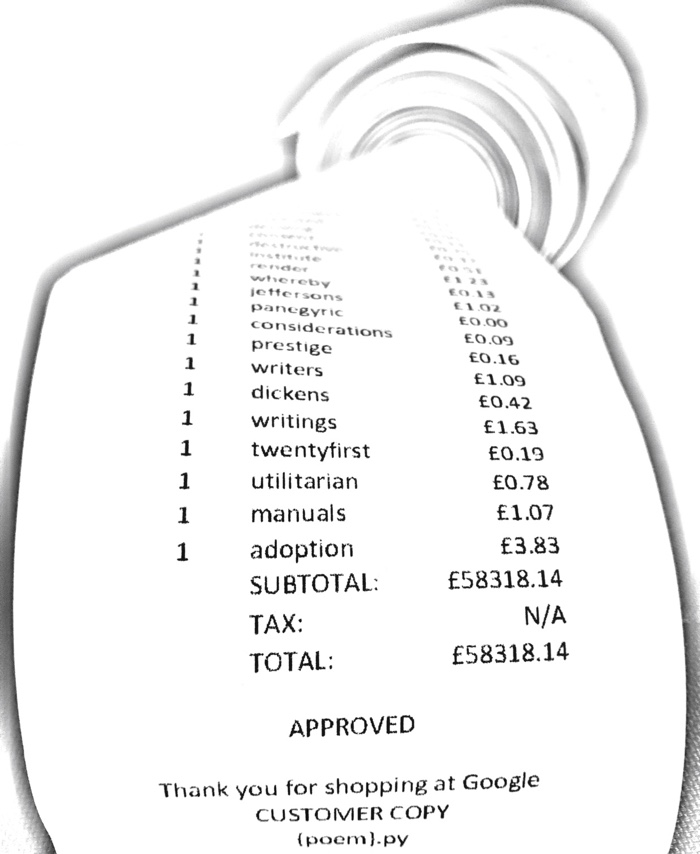

Thornton’s doctoral thesis, Language in the Age of Algorithmic Reproduction: A Critique of Linguistic Capitalism is accompanied by a series of artworks that feed poetry through the Google Ads system. Each of the words in the literary texts she chose are analysed and given an approximate price by Google. The results are then printed out in the form of a receipt.

She was particularly interested in how the Google algorithm would approach Orwell’s Newspeak, a language featured in George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. Newspeak is an extremely controlled language developed by the ruling Party of fictional Oceania to ensure that the grammar and vocabulary are so restricted and poor that it would be impossible for its speakers to articulate any freedom of thought and any other critique of the Big Brother ideology.

Pip Thornton, {poem}.py, 2019. Photo credit: Amy Freeborn

Until recently, the highly lucrative Google Ads system could not be applied to spoken-word poems that had not been transcribed online. This stronghold of resistance has started to crumble now that speech-recognition has improved and that we’ve welcomed Alexa, Siri and other “personal assistants” into our life.

Dr Pip Thornton is a post-doctoral research associate in Design Informatics at the University of Edinburgh. I’ve asked her to tell us more about her research:

Hi Pip! Your PhD thesis, Language in the Age of Algorithmic Reproduction: A Critique of Linguistic Capitalism, was accompanied by creative experiments that consisted in feeding poetry, literary texts and even your own thesis through Google Ads (formally AdWords) in order to communicate and critique linguistic capitalism. How were art and creativity useful to your research?

The creative intervention part of my research was a serendipitous accident, but foregrounding the importance of language as art became an integral method. I wanted to use the power of language – existing poetry and literature, as well as new experimentations and speculative work – to critique digital technologies/economies, rather than just using digital tools and technologies to analyse and experiment on language sitting passively in datasets and corpora. I wanted to give language its agency back as human, emotive language, rather than as a training set, or as a vehicle for the flow of advertising capital around digital spaces, which is what it is increasingly becoming. The monetised poem-as-receipt (the {poem}.py project) began as a simple way of visualising the idea of linguistic capitalism, and conveying it to multiple disciplinary audiences. When I worked out how to actually print receipts, and started framing them, it then kind of automatically turned into art – almost by default – which is interesting, as the words I had so carefully rescued from the algorithmic market then become enrolled in an entirely new market. I tried to make these tensions clear in my thesis, and resist them as much as possible.

Pip Thornton, William Wordsworth’s Daffodils, 2017

Apart from Google Adsense, where else can we observe linguistic capitalism in action?

The definition of linguistic capitalism my thesis stems from is from Frédéric Kaplan’s discussion of Google AdWords in his 2014 article ‘Linguistic Capitalism and Algorithmic Mediation’, but it’s definitely also relevant to other Google platforms such as AdSense (as in its part in the spread of fake news) and GMail. An early inspiration for my own artistic intervention into AdWords was Cabell and Huff’s American Psycho, where they sent pages of Easton-Ellis’s novel through Gmail and collected the adverts that were triggered by the text. They then reconstructed the book physically, leaving the text out, but inserting phantom footnotes to the adverts, thus revealing an economic para-text in which the misogyny and violence of the text is obfuscated by its money-making potential.

For me then, linguistic capitalism occurs when the economic value of words – their exchange value – negates their value in their communicative, or aesthetic sense, with potential collateral effects on the wider discourse. Franco Bifo Berardi calls this the grammar of the digital economy.

I think about it in terms of the illiquidity of language in the digital economy – if words are now tied to an economic derivative value that is more and more distanced and decontextualized from its other – more liquid – values, then do they risk becoming subprime?

Pip Thornton, The price of 1984, 2017. Photo credit: Ray Interactive

Pip Thornton, NEWSPEAK, 2019. Photo credit: Maxime Ragni

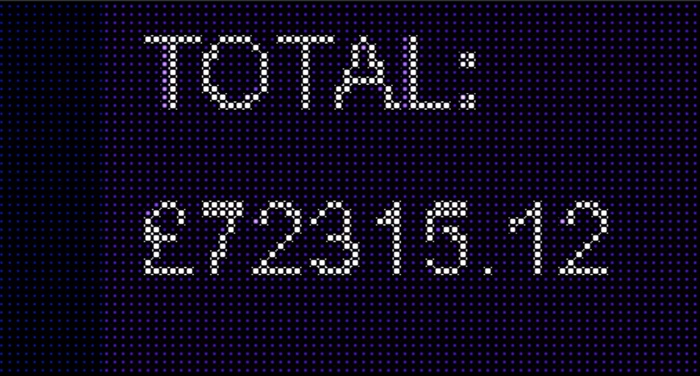

The piece NEWSPEAK involves the whole text of Orwell’s 1984 being shown as a stock market ticker-tape, with the word prices fluctuating according to live data from Google Ads. How fast and how widely does the price of words fluctuate over the course of a day for example?

I haven’t done an in-depth analysis of the changing prices of the words during the NEWSPEAK installation yet. Since Google Ads’ latest upgrade, the estimated bid prices change far more dynamically and quickly than they used to, so I need to update my analysis accordingly. What I can say is that when I first monetised 1984 through AdWords in 2017, and printed it out as a receipt, the text was theoretically worth just over £58,000. The final iteration of NEWSPEAK 2019 came in at around £72,000, so it’s gone up £14,000 in two years!

I haven’t done an in-depth analysis of the changing prices of the words during the NEWSPEAK installation yet. Since Google Ads’ latest upgrade, the estimated bid prices change far more dynamically and quickly than they used to, so I need to update my analysis accordingly. What I can say is that when I first monetised 1984 through AdWords in 2017, and printed it out as a receipt, the text was theoretically worth just over £58,000. The final iteration of NEWSPEAK 2019 came in at around £72,000, so it’s gone up £14,000 in two years!

Have you ever thought about what the ruling parting of Oceania would have made of this way of monetising words?

They’d be raging at Google for pinching their model! The appendix to 1984 gives a full description of Orwell’s vision of Newspeak as deployed in Oceania. It’s specifically a language where words can only be used for a specific and controlled purpose – for example the word ‘free’ can be used to say things like ‘this field is free from weeds’, but can’t be used in a political sense of being ‘free’ from oppression, or intellectually ‘free’. Google’s search and advertising model exercises a similar method of what Anna Jobin and Olivier Glassey have called semantic determinism. Whatever the context of the words we put into the search engine, it is the linguistic market that decides the context of the search results based on the most economically lucrative version of that word – which is not necessarily the one you intended. The best example to illustrate this in my own work is the suggested bid prices for the words cloud, crowd and host in William Wordsworth’s Daffodils poem, all of which have high economic values, based not on Wordsworth’s vision of a Cumbrian springtime, but because of their re-contextualisation as valuable keywords relating to digital technologies such as cloud computing and web hosting. Likewise, in Newspeak, Orwell imagines that words cannot be used for literary purposes. What I think makes the 1984 critique so powerful is that in Oceania, this control of language is overtly deployed as a means of controlling thought, whereas in linguistic capitalism, the political and social effects of this semantic determinism go largely unnoticed, or are somehow dismissed as a quirk, a glitch, or as an acceptable trade-off for the wider perceived benefits of Google’s systems.

Pip Thornton, Intersections (exhibition view), 2017

This year, you worked with Ray Interactive to add a voice recognition element to your project. What did voice recognition bring to your work?

When I began the {poem}.py intervention back in 2015, it was ‘written’ words on the internet I was interested in – specifically the words going in and out of the search engine, so I would only do receipts for poems that I could cut and paste from the web. Conceptually the words needed to have been ‘vulnerable’ to the algorithm in some way. Indeed, the first collection of poems I monetised through AdWords included a VOID receipt for a spoken word poem that only existed as audio on the web.

Spoken word thus became a form of resistance against the forces of linguistic capitalism. However, now just a few years later, with the development of Siri, VOIP calling and home assistants such as Amazon Alexa, as well as developments in the monetisation of audio on YouTube etc, speech and audio are no longer safe from digital exploitation, so I wanted to reflect and explore that in my work.

I started imagining a kind of dystopian future when voice-based technologies are so prevalent that it becomes impossible to speak without our words being monetised in some way, and that what we say starts to be dictated by how much linguistic capital people create in different physical spaces. So maybe data packages or Wifi are dependent on the generation of value through speech, so people would earn social capital from making money in areas where keywords are worth more, such as cities, business/commerce hubs, rich areas etc, but not all people have access to those areas, so social divisions are magnified to the point of unrest or conflict.

To reflect this in my work I wanted to develop a voice activated version of {poem}.py, so that spoken words could be automatically monetised in real time, and also to integrate a physical spatial element – maybe in the form of a maze, or other structure, – to convey the idea (and the frustration), of having your movement through space controlled by how much or how little money you make with your words. It was just a theoretical idea at first, but after meeting Brendan and Sam from Ray Interactive through the Creative Informatics project here in Edinburgh, we managed to make it a reality.

You tested the voice recognition system with a group of playwrights, “asking them to create stories according to the economic value of the words they speak as they walk through and react to different surroundings.” Can you tell us how the experiment went?

Yes – the first time we tested it was at a workshop hosted by the Edinburgh International Festival. We asked playwrights and writers to explain a play or book to their team in three scenes, or stages. We had boxes marked on the floor, and players had to negotiate their way through the space while avoiding running down their team’s budget with what they said. So it was all about an economy of words – trying to avoid using economically valuable language, while at the same time also not losing its communicative and creative value. It was very much a first iteration, but it had interesting results, and we’re hoping to develop it further in the future.

Does linguistic capitalism have any effect on the language people speak in their everyday life? or is it confined to the world of online advertising?

I suppose there are links between online keywords and the buzzwords people use to gain social and economic capital in spoken communication, and of course language always evolves according to changes in technology and other cultural factors. It’s what’s ahead that bothers me though… like I said before, offline communication used to be relatively untainted by this particular form of linguistic capitalism, but it’s becoming more and more normalised for private and public spaces to be monitored or recorded – whether you consent to it or not. This might start as Siri requests being recorded, or data from VOIP calls and home assistants being monitored and monetised, to smart city projects like what Google is planning in Toronto or things like the technologies monitoring schools for audio signals of anger and violence. With the workshop at the Edinburgh International Festival, I wanted to convey the frustration that might be felt if we were to be aware that the words we say might be hoovered up and exploited in various ways, and also to challenge people to think carefully about their choice of words. Participants were encouraged to think of ways to resist linguistic capitalism by conveying messages (in this case plays) to their human teammates in ways which confounded the voice recognition software. For example, it became clear that strong accents are ‘misheard’ by the software, or participants could draw out their words so slowly that they could make themselves understood to their team, but avoid their words being monetised. As a critique of new voice technologies, it worked quite well. People were annoyed that the very basic voice recognition software we used sometimes didn’t understand them, and there was also the aspect that they couldn’t turn it off – players were arguing with off-mic team mates, but it was all picked up and monetised… there was no escape!

Pip Thornton, 1984 (end), 2017

You explained in a Linguistic Geographies post that “the final chapter of my thesis will examine ways of turning this power back around, and ‘making art political’, or more specifically to this project, reclaiming language as art.” Could you tell us more about that aspect of your research?

Yes – the ‘making art political’ part is a direct response to what I argue is an aestheticisation of the politics behind technologies such as Google search and advertising. It comes from Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936). Benjamin was writing in 1930s Europe, where the fascistic politics of the 1930’s had been ‘aestheticised’ by its co-option of popular culture and the myth of inclusion. I argue that a similar thing is happening today – we are lulled into a sense that we have any control or agency by the aesthetics and ubiquity of technologies like Google, and more and more this has extreme political consequences. Benjamin’s call to overturn the aestheticisation of politics required the politicisation of art, which is what I aim to do with my intervention – quite literally embedding the political critique in the material intervention, and re-aestheticising language.

Pip Thornton, 1984 poem.py, 2017

Any other upcoming events, fields of research or projects you could share with us?

I have a piece of speculative fiction coming out soon called ‘Subprime Language and the Crash’. It’s in an edited collection (Kitchin, Graham, Mattern, Shaw 2019) that imagines what would happen if cities were run by companies such as Amazon, Google etc. My piece explores some of the concepts I mentioned earlier. I also want to address Subprime Language from a more academic perspective, so am working with John Hogan Morris on developing the economic and theoretical concepts around such a project. I’m also thinking about the idea of a ‘digital écriture féminine’, an adaptation of Hélène Cixous’s work on the gendered binaries in language – which are so apparent in Google AdWords data- and how we can turn them around through intervention and creativity. Apart from that, I am really keen to take the NEWSPEAK ticker-tape project forward – a monetised version of 1984 playing in Piccadilly Circus or Times Square maybe?

Thanks Pip!