Simon Farid is a visual artist interested in the relationship between administrative identity and the body it purports to codify and represent. In practice, this means that the artist is ‘squatting’ identities that have been constructed by other people for surveillance, marketing or institutional purposes and then discarded.

Simon Farid is a visual artist interested in the relationship between administrative identity and the body it purports to codify and represent. In practice, this means that the artist is ‘squatting’ identities that have been constructed by other people for surveillance, marketing or institutional purposes and then discarded.

Farid notoriously ‘inhabited’ the identity of an undercover police officer and the one of a politician who moonlighted as a web marketing guru.

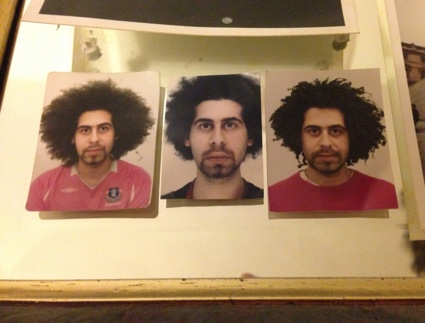

The first identity was the one discarded by Mark Kennedy, an undercover Metropolitan Police officer who spent almost 8 years pretending to be an environmental activist called Mark Stone. To settle into the life of what the UK calls a “domestic extremist,” Stone traveled under a fake passport and used a driving licence and bank cards bearing his borrowed name. But once Kennedy’s cover was blown however, Stone was nothing but an empty shell. That’s when Farid steps in. The artist reactivated Stone’s email address, started collecting library and store cards, opened a bank account and amassed a number of other identity articles under the name of Mark Stone. By doing so, Farid effectively ‘occupied’ the identity that the police officer had abandoned.

Simon Farid, Don’t Hate The Rich – Be One Of Them!

Simon Farid, Don’t Hate The Rich – Be One Of Them!

Simon Farid, Don’t Hate The Rich – Be One Of Them!

Simon Farid, Don’t Hate The Rich – Be One Of Them!

Simon Farid, Don’t Hate The Rich – Be One Of Them!

Simon Farid, Don’t Hate The Rich – Be One Of Them!

His second action involved How To Corp, a “marketing” company fronted by a multi-millionaire called Michael Green. Green’s scheme guaranteed his customers that they would earn ‘$20,000 in 20 days,’ provided that they first shelled out hundreds of dollars to buy one of his ‘Stinking Rich’ (that was the name!) guides. It turned out that Rt. Hon Grant Shapps MP, a British Conservative Party politician, was actually hiding behind the get-rich-quick businessman.

In a performance bearing the irresistible title of Don’t Hate The Rich – Be One Of Them!, Farid reconstructed HowToCorp’s old website which had hastily been wiped out when Green’s activities came to light, built a social media presence and organised performances in which he presented himself as marketing guru ‘Michael Green’.

And because a lot of his artistic work evokes espionage practices, Farid also leads workshops in which participants are invited to impersonate a plain clothes police officer, adopt alternative identities or analyse MI5 job adverts to conjecture on their surveillance practices.

In investigating identity-generation processes, the artist demonstrates that identities are not ours. Identities can be easily hacked, stolen, and sold for peanuts. Much of Farid’s work is thus thought-provoking and slightly disturbing. It is also often quite hilarious. There was no way i would have missed the opportunity to interview him:

Hi Simon! With your Identity Squatting practice, you look for pre-constructed unoccupied identities that you then infiltrate and reanimate. Could you take us through the steps that needs to be undertaken for a successful infiltration?

For my identity squatting work I set myself the task of occupying the found constructed identity to the extent it had previously existed. This varies depending on the type of identity I’m looking at. A discarded undercover police identity will have had an array of identity articles, while the alter ego of a Conservative MP may only have had an image, website and testimonies to its existence. A nice current example I’m looking at could be Sarah and Zac, fictions created and controlled by an, as yet, anonymous DWP worker. A squatting of Sarah may only need use of an image and DWP endorsement. Sarah and Zac turning up to claim sickness benefit after all might be fun…

After identifying the parameters of the target ‘identity’, much of this process is just about gathering information. This can be pretty lo-fi, making use of agencies and resources that have their roots in times past; Electoral Registers at public libraries, the Land Registry, General Register Office etc. There is then a degree of blagging required to gain a foothold in the identity.

After this initial jump, piecing together a discarded identity becomes easier as one progresses. The more information and testimonies one collects, the easier it is to leverage this knowledge to acquire more. Through these processes I have come to see institutional identity increasingly as knowledge; have enough knowledge about someone and systems will begin to understand you as that someone.

With the more detailed squattings, a degree of luck is required. This is of course made much easier by focusing on identities that have spent some time in the public eye.

What are the biggest challenges you usually encounter when ‘resetting’ an identity?

What are the biggest challenges you usually encounter when ‘resetting’ an identity?

The biggest challenge is an ethical one. With politically motivated work like this, the unoccupied constructed identities tend to have previously been used for nefarious purposes (to put it lightly). When putting such identities back together, I am very conscious of their re-appearance being directed at the authority that initially constructed them, rather than their victims. This means careful consideration at every step of the process to re-open these entities only in an institutional sense, rather than a social one. In our increasingly interconnected world, this can be difficult.

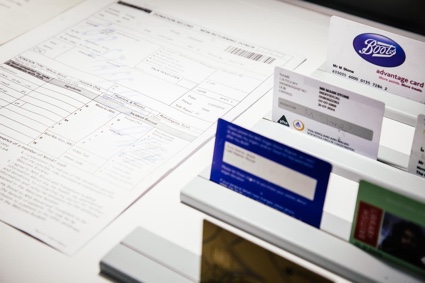

Credit cards and IDs for Mark Stone as exhibited in the SECRET show. Photo courtesy of the Science Gallery in Dublin

Credit cards and IDs for Mark Stone as exhibited in the SECRET show. Photo courtesy of the Science Gallery in Dublin

Credit cards and IDs for Mark Stone as exhibited in the SECRET show. Photo courtesy of the Science Gallery in Dublin

Credit cards and IDs for Mark Stone as exhibited in the SECRET show. Photo courtesy of the Science Gallery in Dublin

Can you really get a bank card without showing a passport or ID card in the UK?

Entry level.

What does it feel like to squat another identity? To walk around town under another name?

For me this is far more interesting than the technical and procedural aspects of acquiring use of a shell identity – of course there are many fraudsters doing this first part!

Walking around a city while registering under another identity is a surprisingly affecting experience. It begins with an initial feeling of illicitness, the excitement of doing something one is not supposed to. But past this, there is a deeper feeling of liberation. Doing this has really highlighted for me the number of identity checks one is subject to all the time and how affecting these can be; a constant series of re-confirmations, like Simon Farid is always in question. To trick these systems (maybe not all of them, but some, sometimes) really does feel like a weight off one’s shoulders.

The thing I can best liken it to is my experience of the London riots in summer 2011. As Hackney burned, I walked the streets alone to stay at a friend’s flat in Dalston. Walking through the wild streets, streets that felt abandoned by authority, was scary yes, but also kind of euphoric. Shaking off Simon Farid feels a bit like this, a riot of one.

Does it affect your behavior in any way?

This is quite funny – outwardly I think one would struggle to notice any difference in my behavior at all. I was still sitting in coffee shops, buying things, looking. These identity shells could be tools to radically alter one’s actions, but for my purposes here, for these identities to re-emerge in different institutional systems, sipping frappe lattes felt like a revolution. I am very interested in these invisible subversions that outwardly look like nothing, but are in some respects quite challenging. In the end, does this mean something?

Or your own sense of identity (as Simon Farid)?

One thing I have noticed when looking back at these experiences was a lack of engagement with the ‘who’ of my new shell identity. In practice, these new institutional identities acted as an anonymising tool, rather than any feeling that I had actually lost Simon Farid and emerged as this new person – hence the feeling of illicitness, rather than comfort.

Maybe this would be different in a more prolonged experience? The longest I operated as another was a few days. There may also be an element of not identifying with the shell identities because these identities are not sympathetic characters – for example, I have no desire to be Michael Green!

These are open questions my work is still dealing with.

Simon Farid, How To Impersonate A Plain Clothes Police Officer workshop

Simon Farid, How To Impersonate A Plain Clothes Police Officer workshop

Credit cards and IDs for Mark Stone as exhibited in the SECRET show. Photo courtesy of the Science Gallery in Dublin

Credit cards and IDs for Mark Stone as exhibited in the SECRET show. Photo courtesy of the Science Gallery in Dublin

Operating as ‘other people’ that actually never really existed. Is there any law against that? What happens if you get caught?

Yes the law is always a worry, and while I don’t feel like I ever cross it, there are risks associated with pushing up against the boundaries, especially where precedent is not so clear.

Looking at powerful institutions and figures can sometimes offer a level of insurance against pushback though. Security services have a rule to ‘never confirm or deny’ undercover identities – this can work in one’s favour when working with these identities. Similarly, while one may risk libel laws through operating as someone else, it would usually be in the claimant’s favour to leave me alone – that way my work only appears in high-end art blogs rather than the Guardian. Working with these tensions and obstructive rules can be a fruitful tactic.

Nonetheless, I have to be very careful of my security, and speaking openly about this work here still feels a little uncomfortable.

Why did you start squatting identities? Did you dream of being Cindy Crawford when you were young (i was!), for example?

Trying to be other people is a big part of childhood play of course – I remember often being Duncan Ferguson while playing in the park, though ‘cops and robbers’ may be more instructive here!

More concretely, this work emerged out of an interest in role-play and performativity in everyday life. I am very interested in the hundreds of small performances we present each day in different institutional and social situations. Investigating figures that had taken these performances to an extreme, codified level seemed like a logical next step.

Powerful people and institutions are very adept at being different people at different times. An aspect of this work is to explore whether such tactics can be useful from below too.

Simon Farid, MI5 Mobile Surveillance Officer Training workshop

Simon Farid, MI5 Mobile Surveillance Officer Training workshop

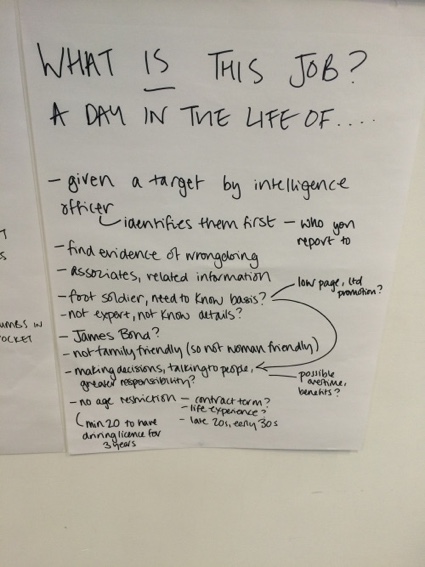

I would have loved to participate to your MI5 Mobile Surveillance Officer Training workshop at the Science Gallery in Dublin. What was the workshop like? What did you and the participant discover?

The workshop centred on looking at an MI5 job advert for a ‘Mobile Surveillance Officer’. These adverts are publicly viewable here: https://recruitmentservices.applicationtrack.com/vx/lang-en-GB/mobile-0/appcentre-a18/candidate/jobboard/vacancy/1.

The adverts themselves are really interesting documents. Of course, they can’t be too revealing – this is MI5! And yet, they still need to offer some kind of indication of the job on offer. The result is a strangely opaque document, but one that may offer some small insight into a very secretive organisation.

In the workshop the participants and I, after some discussions about the types of surveillance we partake in, analysed an MI5 job advert to see if we could identify any aspects of the job that might be worth trying out. I had purposely selected the Mobile Surveillance Officer advert for the workshop as this looks like a very interesting, following-based job, unlike most of the jobs that, as you can see, are computer-based.

Through this process we were able to develop a kind of game based on following apparent members of the public, live-reporting our positions using compass points and following coded directions. The outcome was something that approached a mindfulness exercise, looking closely at one’s body in relation to space and time, while heightening awareness of the range of surveillances one’s body is subjected to in urban spaces.

Do you realise that MI5 should probably hire you?

I assume you assume I don’t already work for MI5? I am within the right height restrictions (males need to be shorter than 6’1) and suitably untattooed.

All their adverts warn of a pretty in depth background check though. I hope I wouldn’t pass it!

With this question you do hit upon an important question about artist-infiltrators. It is something we discuss in all my workshops; I would be surprised if they have never been attended by a security worker keeping an eye on things. We have seen evidence of CIA involvement in Abstract Expressionism. I expect the arts are a heavily monitored, if not infiltrated, area. Is there anyone you suspect?

No one so far but from now on i’ll be more vigilant.

Has your work and expertise in hijacking other identities affected the way you communicate and protect your online identity?

Working in these areas has meant I have had to be very conscious of online security at times. Post-Snowden, I think it has become apparent that communicating online is never reliably safe, secure and secret. As such, I would like to communicate on the internet as little as possible – but obviously if I want funding and interviews like this one, I have to be relatively open and visible online (this is one of the ways they get you, this false choice). So for me it has become more a matter of selection; if I ever want to communicate securely I don’t do it online. Otherwise, hi GCHQ!

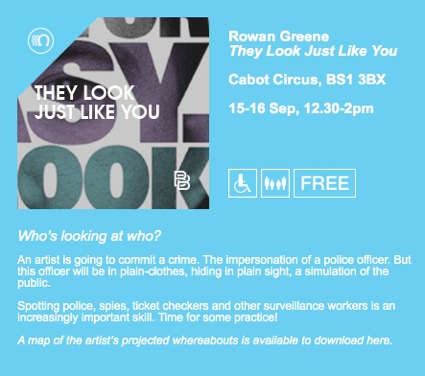

Simon Farid, They Look Just Like You

Simon Farid, They Look Just Like You

I laughed when i read the title of one of your workshops: How To Impersonate A Plain Clothes Police Officer. Is that really so hard to do?

Well this workshop did start as a kind of one-line joke, the committing of a crime (impersonating a police officer) that was so invisible as to be non-action; look around you, maybe everyone is impersonating PCPOs?

But the more I thought about plain-clothes surveillance, the more I began to see nuance. Covert surveillance workers have many potential identifying signs; operating in twos, being more observant than your average commuter, not hurrying to a destination etc.

So this workshop developed more into a ‘How To Spot Covert Surveillance Workers’ workshop. And, as with a lot of my work, I find the best way to learn something is to try it out for oneself.

Simon Farid, Don’t Hate The Rich – Be One Of Them!

Simon Farid, Don’t Hate The Rich – Be One Of Them!

What’s next? Any upcoming work, exhibition, workshop or research you’d like to share with us?

Next up for me is a workshop for Live Art Development Agency’s DIY12 called Nothing To See Here. In this workshop I’ll be pulling together a lot of these undercover experiments to look more directly at whether covert tactics can form the basis of a meaningful performance practice.

Otherwise, on the back of the MI5 Mobile Surveillance Officer workshop I’ve started a project trying to map out the departmental structure of MI5 using the job adverts. In many of the adverts they mention other job titles that the advertised job works with/under/over. By looking at a large number of these adverts, I hope to be able to eventually map out the whole structure of MI5 and get a better sense of the organisation’s scale. I’ve written about the beginnings of this process here – http://simonfaridblog.tumblr.com.

Thanks Simon!

Check out Simon Farid’s Occupy Mark Stone at the Science Gallery in Dublin. The work is part of SECRET, an exhibition that runs until 1 November 2015.

Thee artist will also participate to the Warrington Contemporary Arts Festival with Nothing To See Here, a workshop that will explore what arts performers can learn from covert and surveillance workers.