September 2004. My first Ars Electronica. I knew nothing about media art and loved everything i saw there. When i look back i’m a bit less elated, though i still won’t listen to the party poopers whose favourite game is to sneer at what they see in Linz. Each year i feel like a kid in Wonderland at Ars. Anyway, three years after my first ars, i still believe that the Seven Mile Boots are one of the most extraordinary piece of art i’ve ever seen at the festival. This pair of boots allows their wearer to wander through virtual space. When walking, users stroll through the net, when standing still they can listen to several chat rooms simultaneously. They were created by Laura Beloff, Erich Berger and Martin Pichlmair.

September 2004. My first Ars Electronica. I knew nothing about media art and loved everything i saw there. When i look back i’m a bit less elated, though i still won’t listen to the party poopers whose favourite game is to sneer at what they see in Linz. Each year i feel like a kid in Wonderland at Ars. Anyway, three years after my first ars, i still believe that the Seven Mile Boots are one of the most extraordinary piece of art i’ve ever seen at the festival. This pair of boots allows their wearer to wander through virtual space. When walking, users stroll through the net, when standing still they can listen to several chat rooms simultaneously. They were created by Laura Beloff, Erich Berger and Martin Pichlmair.

A few weeks ago, i was participating to the Mobile Music Workshop together with Martin and lucky me! he agrees to answer a few questions.

Martin Pichlmair is a media artist, practitioner and theorist whose art works have been exhibited at prestigious festivals such as ars electronica, ISEA and microwave. He is also working as assistant professor at the Institute of Design and Assessment of Technology at the Vienna University of Technology. His research focuses on theory and practise of interactive art and design – from game design and physical interfaces to open source development models and community media.

You received a doctoral degree in informatics and work as assistant professor at the Vienna University of Technology. This is a serious background and i suspect that your current job is keeping you busy. So how did you get into art? And how does your work at the University connect with your art practice and vice-versa?

You received a doctoral degree in informatics and work as assistant professor at the Vienna University of Technology. This is a serious background and i suspect that your current job is keeping you busy. So how did you get into art? And how does your work at the University connect with your art practice and vice-versa?

I always knew that I want to do art. I chose to study computer sciences because I thought that learning technical skills is more important than what an art university can teach me … That kind of thoughts you have when you are nineteen. Before studying I did drawings and etchings, programmed some simple computer games, and wrote poems and theatre plays. After some years of studying informatics I had to re-approach art from a more technical perspective. Through a friend I got the opportunity to join the Ars Electronica Futurelab for a couple of months. That was like a crash-course in media art. The supervisor of my doctoral thesis, Peter Purgathofer, also kept pushing me towards media art. Through him I was able to marry my profession and my other profession.

Of course my job is keeping me quite busy. But I was hired to research and teach exactly what I need for my art practice – and the other way round. Everything connects quite well. On good days it feels like getting paid to do your own media art projects. On bad days I realise that I often have to travel afar to get inspiration from fellow artists, since my university is a technical university.

I first got across your work at ars electronica when they exhibited the seven mile boots that you developed together with Laura Beloff and Erich Berger. Can you explain us what was the impetus for that project and what were the biggest challenges in developing the piece?

Like so many of my art pieces it all started with a device. Laura brought along an iPaq, a pocket PC, after we both agreed that we want to do a mobile piece together. While both of us embrace technology we are still concerned with the lack of imagination in technology and especially mobile communication (you can see that clearly in Laura’s

Like so many of my art pieces it all started with a device. Laura brought along an iPaq, a pocket PC, after we both agreed that we want to do a mobile piece together. While both of us embrace technology we are still concerned with the lack of imagination in technology and especially mobile communication (you can see that clearly in Laura’s

recent pieces like the fly farm). So we wanted to make a critical, even nasty, piece of art. The three of us developed several iterations of wearable pieces. One could say we did a lot of prototyping. In the end we settled for the unpredictable, capricious boots. A non-locative mobile piece about the personal experience of being surrounded by mass communication. Instead of boiling down mobility to the personal experience at a specific place and time, as it is done in so many locative art pieces, we wanted to broach the issue of the ubiquity, unpredictability, permanence, and location-independence of communication. Of course that is only a part of the whole picture.

There were a lot of challenges while doing this art piece. That’s why it took so many years. The biggest was for sure that we are living in different countries. Laura and Erich lived in Norway most of the time, back then. We only met every couple of months, but then we worked very intensely for a few days or weeks. Then there were of course the expected, typical technical challenges of mobile art pieces: weak machines that use too much power, unreliable sensors and cabling, the choice of the right materials, etc. We had to switch sensors a couple of times, and I think I programmed the software at least thrice. When it comes to exhibiting the piece, the most interesting challenges are the preconceptions people have about boots. But those are a part of the art piece. People quickly attach to them and project their very own expectations and imaginations on the boots.

FAMULUS is an intelligent modified vacuum cleaner meant to substitute the desktop metaphor feature of the trash bin. How does it work technically? What inspired the project?

FAMULUS is an intelligent modified vacuum cleaner meant to substitute the desktop metaphor feature of the trash bin. How does it work technically? What inspired the project?

Technically it works over cable. So it is not mobile in that sense. A vacuum cleaner without cable is not a vacuum cleaner anymore. The cable is connected to a server that does all the work of receiving spam mail and turning it into noise. My problem with this piece is that the original device I started with is stronger than any art piece I can build out of it. The vacuum cleaner model I use, produced by the Styrian company Famulus in the 1930s, is already such a perfectly beautiful piece of design, it is very hard to retrolutionise. The project was of course inspired by both – the stupidity of the desktop metaphor and the masses of spam I receive every day. I think I have to redo this piece as FAMULUS2 before I ever show it.

Another project you worked on together with Laura Beloff is called Tratti. The devices generate noise and sound and music according to what the kid is looking at. Can you explain us how this colour code works?

The colour code started off as a technical necessity. The piece should be controllable to a certain degree. But we did not want to have any controls on the instrument itself. The colour system turns the surroundings that you play with into an interface, into a score. Different colours trigger different manipulations of the audio you speak into the device. Of course the mapping between a specific colour it is pointed to and what it generates out of it is arbitrary. That is how musical instruments work: If you train and stay disciplined you get an exact tune. But often it is more fun and rewarding to just fiddle around. Both ways of playing should be possible with the system we are designing.

A few weeks ago, at the Mobile Music Workshop, you mentioned that Tratti might look too much like a design piece. Is that a good or bad thing? Can you elaborate on that?

A few weeks ago, at the Mobile Music Workshop, you mentioned that Tratti might look too much like a design piece. Is that a good or bad thing? Can you elaborate on that?

I would not say that TRATTI looks too much like a design piece for us, but it might do so for others. It is a very straight-forward musical instrument. Since it is aimed for kids it has to be manufactured to be very rugged. It has no decoration beside the colour of the plastic parts. And it features a very timeless – maybe even retro – style. You could shoot beautiful photos of TRATTI for glossy design journals. For this piece I think that fits very well.

It is interesting to see how differently and art piece is perceived when it is designed in that way. People compare it to devices and toys rather than to other art pieces. And they are asking us what is the reason for doing this piece and what the piece is for. No one would pose these questions if TRATTI was clearly an art piece. Personally, I do not care too much about the invisible permeable border between art and design but if we shift or cross it we should do so attentively and purposeful.

I’m quite intrigued by your clocks that spin faster than time. What are they exactly?

I’m quite intrigued by your clocks that spin faster than time. What are they exactly?

The clocks were done for an exhibition on Alice in Wonderland that I did together with the off-theatre group toxic dreams called “Jabberwocky“. This piece is not interactive simply because you should not interact with time. I bought a bunch of clocks (I think there are seven) at flee markets and antique stores, opened them up and exchanged parts of the clockwork with a slow geared electrical motor. It is hard to tell what it is about them that makes them immediately fascinating. If you are in a room where seven clocks spin at different speeds, all of them faster than real time, it makes you feel odd in a very substantial way.

Is there anyone or anything you would like to work for?

Not really. I am not good in working for anyone but myself. Of course there are people I would like to work _with_. In the moment I am trying to get used to the fact that people work for me.

Any upcoming project you could share with us?

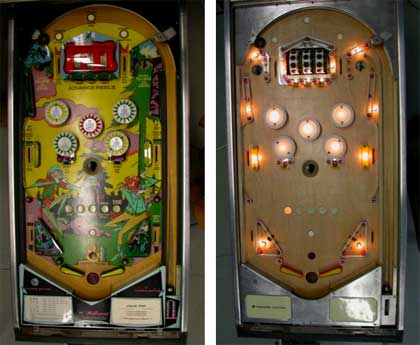

Pinball before and after appropriation

Pinball before and after appropriation

Of course. I would like to take this opportunity to point you to my (nearly finished) newest piece. It is called Bagatelle Concrète and based on a pinball machine from the 1970s. The piece is another musical instrument, a pinball machine that constructs music. It samples itself and manipulates those samples according to how you play pinball on it. We removed all competitive and all decorative elements of the pinball game and put digital electronics into this analogue electro-mechanical machine. While the gameplay is technically unaltered – all the bumpers and traps are still in place – the effect of playing is a composition instead of a highscore. Bagatelle Concrète is related to and inspired by musique concrète and Japanese musical media art pieces like Fujihata’s “A small fish”, Toshio Iwai‘s music games, and Maywa Denki‘s instruments. I am submitting the piece to a number of

festivals. Before it goes on any show there will be a public beta test here in Vienna at the end of June at a dorkbot event.

(video)

You seem to be a pretty successful young artist, having exhibited internationally and at the most prestigious festivals. Do you have any advice for young would-be media artists?

Thanks for the flowers. I do not think that I am particularly successful or well known, but if I am it is only because I work with the right people. Those come from very diverse backgrounds: photography, music, theatre, fine art, philosophy, film, sociology, design, etc. All of them are professional in what they do. That is maybe the most important advice I can give: Work with the pros while you are young. Learn from them.

Martin’s studio/office

Martin’s studio/office

It also helped me that I decided some years ago that I rather want to do few large art pieces than many small ones. That protects from getting distracted. Another important thing (that sounds quite trivial) is: work as good as possible. While critique of curatorial practices in media art is sometimes appropriate, one thing is sure; strong pieces supersede. That of course also involves doing pieces that attract and challenge the audience at the same time. The last advice: being a workaholic and having fun helps a lot. (Now I really feel like a professor ;-).

Thanks Martin!