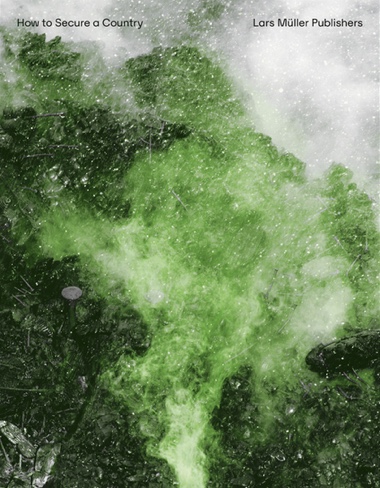

How to Secure a Country. From Border Policing via Weather Forecast to Social Engineering—A Visual Study of 21st-Century Statehood, edited by Salvatore Vitale and Lars Willumeit. With essays by Roland Bleiker, Philip Di Salvo, Jonas Hagmann, Salvatore Vitale and Lars Willumeit.

Lars Müller Publishers writes: Switzerland is well-known as one of the safest countries on earth and as a prime example of efficiency and efficacy. One of the central reasons that such a country exists is the development of a culture based on protection, which is supported by the presence and production of national security. When in 2014 Swiss people voted in favor of a federal popular initiative “against massive immigration,” Salvatore Vitale, an immigrant living in Switzerland felt the need to research this phenomenon in order to comprehend where the motives for this constant need for security originate and how they became part of Swiss culture.

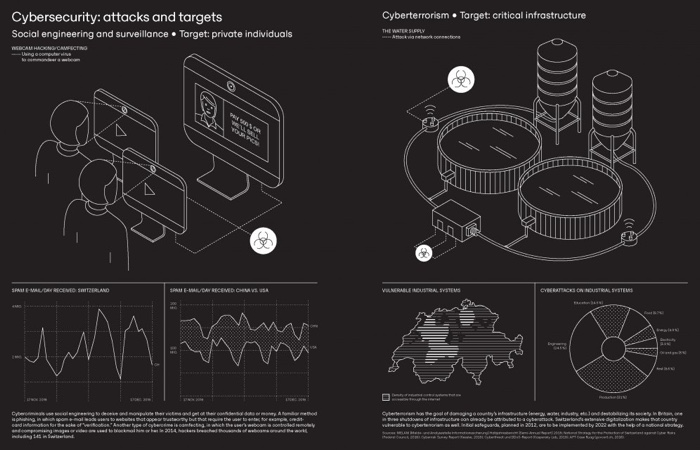

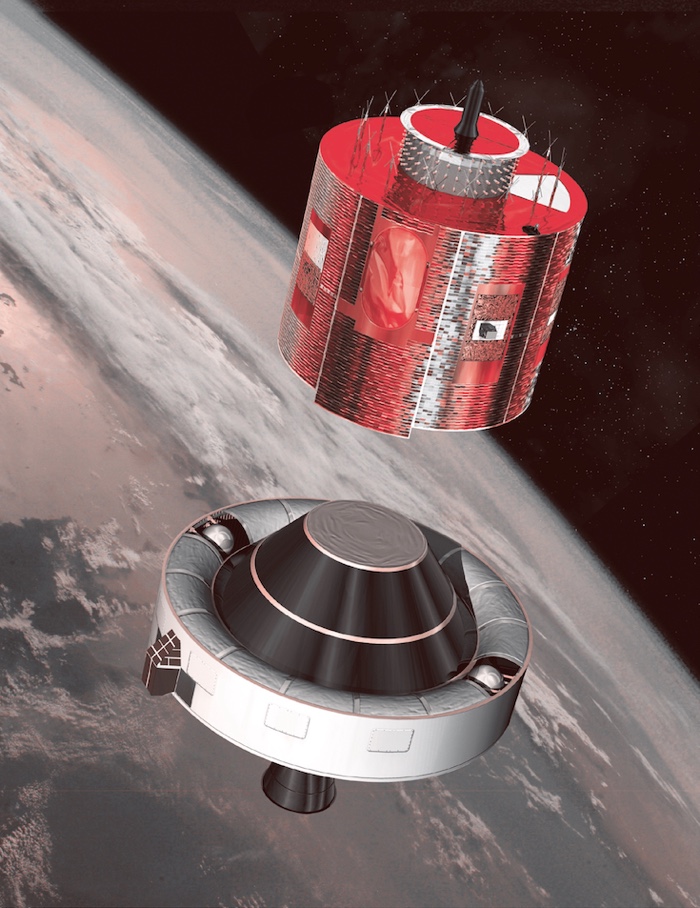

In How to Secure a Country Vitale explores this country’s national security measures by focusing on “matter-of-fact” types of instructions, protocols, bureaucracies, and clear-cut solutions which he visualizes in photographs, diagrams, and graphical illustrations. The result is a case study that can be used to explain the global context and the functioning of contemporary societies.

Fake injured people during a military exercise while staging a terrorist attack happening in Switzerland, from the series ‘How to secure a country’ © Salvatore Vitale

Entrance of a bunker in an apartment building. Until the 80’s it was mandatory to build bunkers in private and public spaces to be ready for a possible nuclear war, from the series ‘How to secure a country’ © Salvatore Vitale

Photographer Salvatore Vitale spent 4 years investigating the security apparatus that ensures that Switzerland remains “the safest country in the world”. Both for its own citizens and for the private banks, pharmaceutical films, multinational companies and cryptocurrencies that rely on its data bunkers to keep their secrets safe.

How to Secure a Country is not a manual. Neither is it a documentary work or a piece of agenda-based activism. It is a visual research project made of photos, essays by political scientists and data visualisation works. Together, these elements give a presence to social, political, technological and psychological mechanisms that are otherwise invisible or simply too complex and abstract to flesh out.

Vitale gained access to places that are otherwise closed to the public. The ways he details the procedures followed by the police, the military, migration authorities, weather services, research institutions for AI build up an atmosphere of protection inhabited by dilemmas and tensions: How much freedom do citizens accept to relinquish in exchange for security and protection? And how do you determine which threats should be prioritized? Is the overuse of natural resources more alarming than cyberterrorism? Declining birth rate more dangerous than energy shortage?

A customised assault rifle transformed for sport purposes, from the series ‘How to secure a country’ © Salvatore Vitale

Lake police agent going on a patrol during a rescue mission, from the series ‘How to secure a country’ © Salvatore Vitale

The book is compelling, both visually and conceptually. It is about Switzerland with all its idiosyncrasies (a Swiss army knife is not considered weapon by the law, the country has enough nuclear fallout shelters to accommodate its entire population) but its content also concerns inhabitants of other parts of the world where predictive policing-software extensive is trusted more than human common sense, where digitalisation is accompanied by cyberterrorism and security practices are increasingly subject to political agenda-setting and influence-seeking.

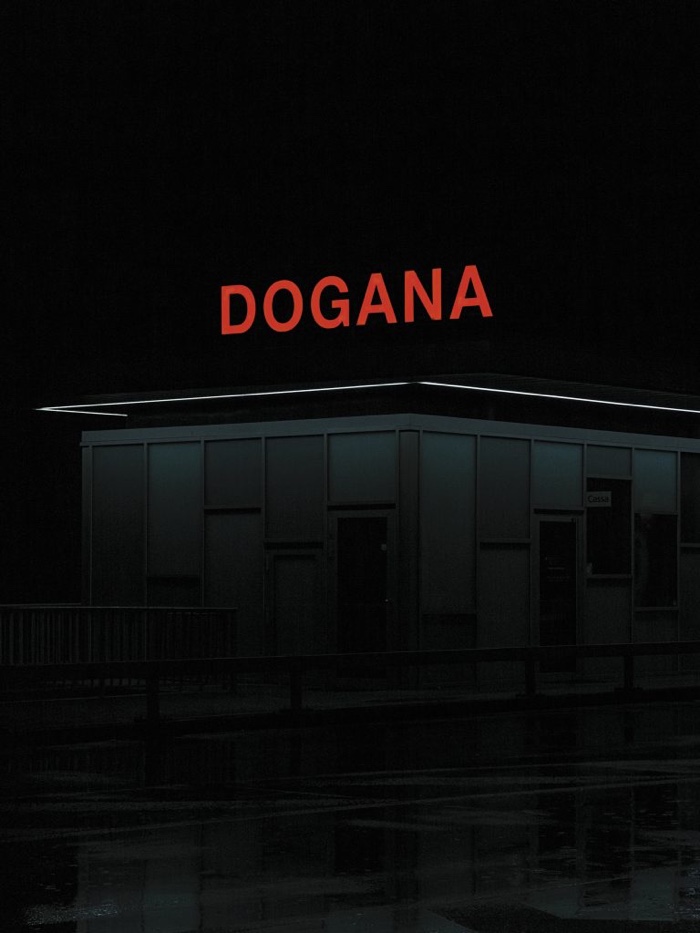

Sign of a custom at the CH–IT border, from the series ‘How to secure a country’ © Salvatore Vitale

Fingerprint registration during an immigration control at the Italian border for an Eritrean asylum seeker, from the series ‘How to secure a country’ © Salvatore Vitale

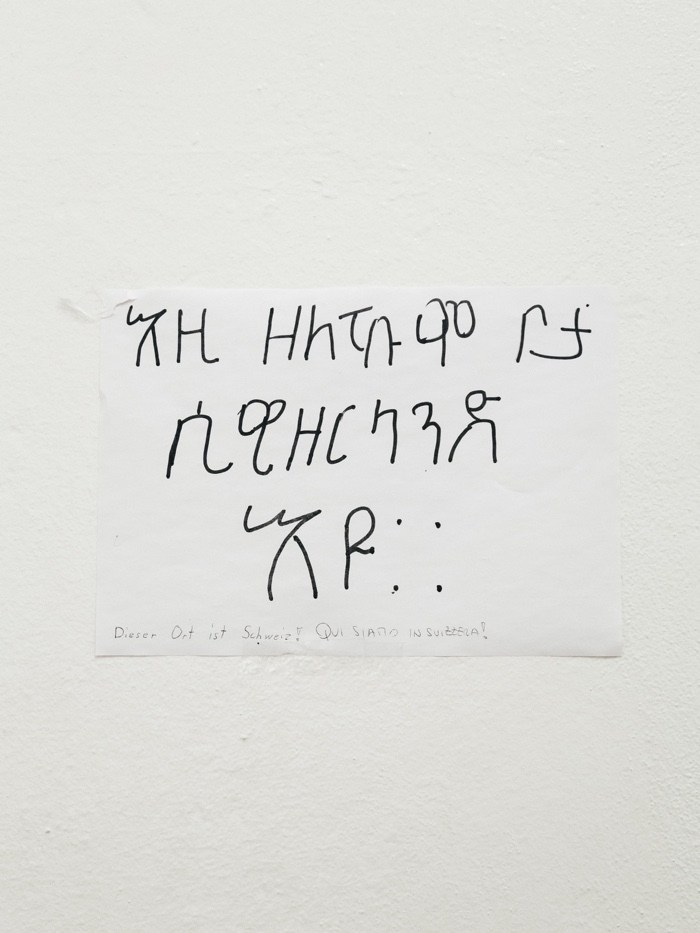

A sign written in Eritrean language at the border saying: “Here we are in Switzerland”. Placing these signs is needed as the majority of migrants aren’t aware they are crossing a border entering another country and they don’t speak any other language than their mother tongue, from the series ‘How to secure a country’ © Salvatore Vitale

A canine unit’s dog looking for drug during an operation in the Canton Zürich, from the series ‘How to secure a country’ © Salvatore Vitale

Security cell in a custom at the border, seeker, from the series ‘How to secure a country’ © Salvatore Vitale

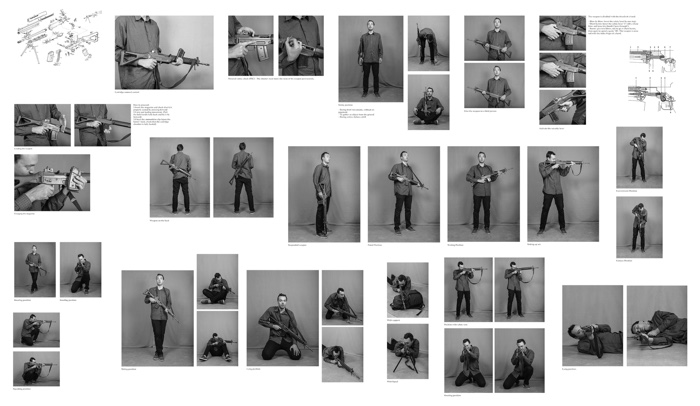

Reproduction of the positions indicated in the official instruction manual of the Swiss assault rifle SIG SG 550, the most common rifle between army and civilians in Switzerland, from the series ‘How to secure a country’ © Salvatore Vitale

Spreads from the book: