I didn’t get the chance to see Five Thousand Generations of Birds but the idea and its result are so seducing i thought i should write something about it. Five Thousand Generations of Birds was an exhibition located in the archipelago of Fitjar, on the West coast of Norway, – a landscape consisting of 381 islands, isles and reefs.

Curators Silje Linge Haaland and Andrea Bakketun assigned an island to each participating artist with the mission to produce a temporary and site specific work.

Roman Signer planted a pair of blue boots on poles on a reef. Not only is the reef in the middle of nowhere but it is not even visible when the tide is high.

Roman Signer, Ladder with Boots. Photo by Erik Reitan

Roman Signer, Ladder with Boots. Photo by Erik Reitan

Joanna Malinowska asked an opera singer to stand and sing on one of the isles.

Johanna Malinowska. Photo by Erik Reitan

Johanna Malinowska. Photo by Erik Reitan

Miks Mitrevics chose to spent 15 days in complete silence on one of the isles. All by himself and sleeping in a shelter he had built. He communicated through letters he sent on a floating mailbox in the sea. The locals brought him fresh fish to eat, sheep for company and magazines for entertainment on their own initiative.

Miks Mitrevics living on one of the isles for the project “15 days of silence”. (Photo: Juuso Noronkoski)

Miks Mitrevics living on one of the isles for the project “15 days of silence”. (Photo: Juuso Noronkoski)

Miks Mitrevics. Photo by Erik Reitan

Miks Mitrevics. Photo by Erik Reitan

Norwegian duo aiPotu measured an island, transporting a big tree from land by sea and using it as the measurement.

aiPotu. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

aiPotu. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

Five Thousand Generations of Birds showed art that interrupts, disrupts and transforms the landscape and the local community. In the end the exhibition -which lasted only a couple of days- all was back to normal. The islands, isles and reefs are ruling the landscape almost as if nothing ever happened. The only difference is that the local communities and visitors are probably looking at it with another eye.

Well, as i wrote, i wasn’t there to experience it but that didn’t prevent me from asking the curators to tell me about the project:

Idan Hayosh and Adam Etmanski transporting their work to one of the isles. (Photo: Juuso Noronkoski)

Idan Hayosh and Adam Etmanski transporting their work to one of the isles. (Photo: Juuso Noronkoski)

Hi, Andrea and Silje! The way you made Five Thousand Generations of Birds is probably as fascinating as what you made. Could you tell us about the challenges in logistics (transport, construction, shipping, etc) you encountered while preparing the exhibition?

Obviously, most of us were not used to these kinds of logistics. Working on tiny isles could be compared to working inside a bus, driving in circles in a roundabout, with the windows wide open, without seats, and without a driver. Still, it hasn’t been more challenging or time consuming than we expected. We wanted the logistics to be an intrusive part of the process.

On the other hand, to actually live there and never be able to escape the context was more of a challenge than what we expected. After work every day, the artists where shipped to their residence at a small island called Engesund, and had to stay there until the local boat drivers started their shift around 10 o´clock the morning after. Some said that at first it felt like some sort of a claustrophobic art prison, but after a few days, this prison created an unique atmosphere and an open dialogue between the artists.

The projects were in constant change, not only due to artistic freedom, but also due to the fact that the exhibition space was regularly modified by storms, heavy rain, wild sheep eating the art, etc. This lead to quite a few problematic practicalities that had to be solved during the last days. Thanks to resources that seemed to appear as if by magic, and a lot of enthusiastic people, we were able to make it happen.

Julien Berthier. Photo by Erik Reitan

Julien Berthier. Photo by Erik Reitan

One example is the work of Julien Berthier (FR). After finding the geographical center of Fitjar and detaching it from its ground, he wanted to transport the 3,2 meters in diameter and 650 kilos center with a helicopter to place it on his isle. Fortunately the first windmill for a huge windmill park in the Fitjar mountains was being shipped at this time, and there was a lot of helicopters cruising around in the area, so one of the helicopter drivers agreed on shipping the center of Fitjar in between the windmill-work.

Tori Wranes

Tori Wranes

Another example is Tori Wrånes (NO) diving board. She needed to mount the board on a cliff wall for her performance. A good climber was required for this task. After talking to some of the locals it actually turned out that an Australian free-climber was hanging out in Fitjar, just waiting for adventures, he was booked and was a great recourse during the rest of the project.

All in all, several projects could not have been realized without us partly relying on the strategy of chance. A strategy that is used by many of the locals in Fitjar, they say you just have to spread the word, and everything is pretty much solved within an hour.

Sigmund Skard. Photo by Erik Reitan

Sigmund Skard. Photo by Erik Reitan

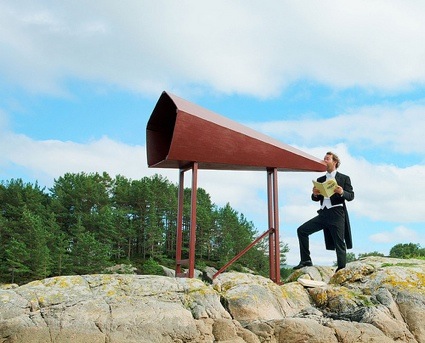

Siri Schippers Skaar, sound gong, 2012. Exhibition Weekend. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

Siri Schippers Skaar, sound gong, 2012. Exhibition Weekend. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

Ftgofbirds takes place on the archipelago of Fitjar which is made of 381 islands, isles and reefs. I suspect you must have met with some ecological concerns when you submitted the idea of organizing this weekend of site specific works. Did you have to meet requirements related to the land or the eco system for example? Did any of them force you and the artists to modify some of the projects or modes of operation?

As we started the process of getting permission to work at the islands in 2009, we already knew that we wanted to emphasize production on site, which meant no shipping of finished works from around the world. This strategy of course limited the amount of materials available, but increased the involvement with the local community and also saved the amount of transport needed.

Taking a look at the history of Fitjar and other places along the Norwegian coast, you don’t have to go more than 60-80 years back in time to find documents of how people who lived on the islands had to risk their lives when rowing out to buy materials for their farms and houses. There are plenty of stories of people who drowned as their boats were caught by bad weather, and the only traces left to find were pieces of wood floating on the water. The stories have set a dark, uncanny backdrop for us as artists in our constant hunt for materials.

Concerning requirements we were not allowed to make any permanent marks in the landscape except from drilling a few holes with a maximum of 12 millimeter diameter on each isle.

Øyvind Aspen. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

Øyvind Aspen. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

This rule shaped some of the artists work. One of them, Øyvind Aspen (NO), worked with the idea of a tiny drilled hole as the only permanent, physical mark anyone could make and drilled a 13 millimeter hole in his island. The performance based installation was titled; “One out of two mystical possibly magical passages tumbling the hell away from this godforsaken place.” His character Øy-vind (island-wind), a mixture of a hillbilly/magician/fisherman, was spotted cruising around in Fitjar on a scooter, flirting with the local teens, visiting the area, while handing out flyers with information of this proclaimed passage.

As the only inhabitants on the isles, the birds that usually live there were a big concern during the production, but as the hatching season was over, the birds easily relocated to the neighbour isles.

Exhibition Weekend. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

Exhibition Weekend. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

Exhibition Weekend. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

Exhibition Weekend. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

I’m also curious about the local communities. How did they react to the project?

The local community has been a very important part of the project.

We thought it would be a struggle to engage the local communities, but they proved us wrong every time we came up with a new idea. People have been curious and eager to work with us.

Ever since the municipality got involved, we have regularly visited Fitjar to have meetings with a local resource group who have been helping out with logistics, etc. Without this connection the project would have been very hard to conduct. A couple of weeks before the exhibition, we sent a very informal letter to all the residents at Fitjar, introducing us and the project and giving everyone an invitation to the exhibition. Approximately 2500 people visited Five Thousand Generations of Birds during the weekend, most of them from the area, and Fitjar is a small town of only 3000 inhabitants. We heard this after we left: “There is a new era in Fitjar. Before and after Erlend Helland, (the local taxi driver), attended an art exhibition.”

Kunstverein St. Pauli, a nomadic gallery that came from Hamburg to join the programme brought a tattoo needle with them, so that people could get free island tattoos. Several artists, the crew, volunteers and the audience got tattoos with one of the islands surrounding Smedholmen.

Kunstverein St. Pauli. Photo by Erik Reitan

Kunstverein St. Pauli. Photo by Erik Reitan

What guided the selection of artists? And according to what criteria did you attribute an island to each one?

We are both artists, and wanted the strategies to be based upon artists inviting artists. The selection has been made from several criteria related to our intuition, association, our common sense of humour, but most of all we have have been working together for so many years that we just created our own sense of logic related to this project. This logic or these rules are hard to categorize or even grasp, and they have been changing alongside the constant work in progress.

Other important aspects guided our selection:

– We wanted to approach the process in the same way as we would do in our artistic production. The site is also a logical choice based on our own artistic production.

– The artists we chose were selected based on who, in different ways, would be interesting to challenge with the restrictions an isle provides.

– Getting to know their existing practice, also knowing that most of them would work completely different faced with the landscape at Fitjar and the challenges of an isle.

– Some of the artists work a lot with documenting actions in landscapes similar to Fitjar, and what is left is the documentation of their actions. We wanted to show the action when it happened, showing their failing and trying, and then the audience could document it in their own way. Maybe it is exactly the fragility and honesty which is needed (to make the audience wanting to tattoo an isle on their chest after seeing the show) to move towards the reality of a site. Without being to pragmatic, and without meaning reality as something non-mystical or non-magic, rather the opposite.

Each of the works created was temporary and site-specific but do you think that they might also leave something permanent behind them?

We wanted the exhibition to be temporary. We wanted the works to be seen within two days by the audience. For a sculpture-based work, this is a relatively short time, but for a performative work, the duration had to be up to 8 hours since we wanted all the works to be present at the same time.

There might be some actual physical traces of the works left behind, even though we wanted the landscape to appear untouched after the show was over, it was a strong request from the locals that we would leave some of it there. Roman Signer donated his sculpture “Ladder with Boots” to Fitjar. This can hopefully be seen for many years, and it’s interesting to see what happens over time to a work that is meant to be temporary.

Other artists donated their works to the volunteers of the projects, some of the sculptural works can be seen in gardens around Fitjar.

The geographical center of Fitjar is also marked permanently with the pole Julien Berthier put down after ending his project.

The permanent effect will be easier to talk about later, after we have visited again, and after the stories related to the project have spread.

A local change should not be underestimated.

The documentation of the exhibition, and the tales of before and after, have been difficult, as the images and the words could romanticize this kind of artistic practice. The experience of being present during the exhibition was much more subtle and demanding.

Serina Erfjord. Photo by Erik Reitan

Serina Erfjord. Photo by Erik Reitan

Marla Hlady. Photo by Erik Reitan

Marla Hlady. Photo by Erik Reitan

Idan Hayosh. Photo by Erik Reitan

Idan Hayosh. Photo by Erik Reitan

Exhibition Weekend. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

Exhibition Weekend. Photo by Juuso Noronkoski

Axel Linderholm. Photo by Erik Reitan

Axel Linderholm. Photo by Erik Reitan

All images courtesy of the curators.