Another year, another intense and satisfying DocLab: Interactive Conference in Amsterdam. The event is a one-day meeting for filmmakers, producers, artists, designers, entrepreneurs and anyone else interested in exploring how digital technologies and new forms of interactivity are shaping the future of documentary storytelling. The conference is one of the highlights of the Seamless Reality program set up by IDFA DocLab, a festival program for ‘undefined art and unexpected experiences’ within the IDFA, the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam.

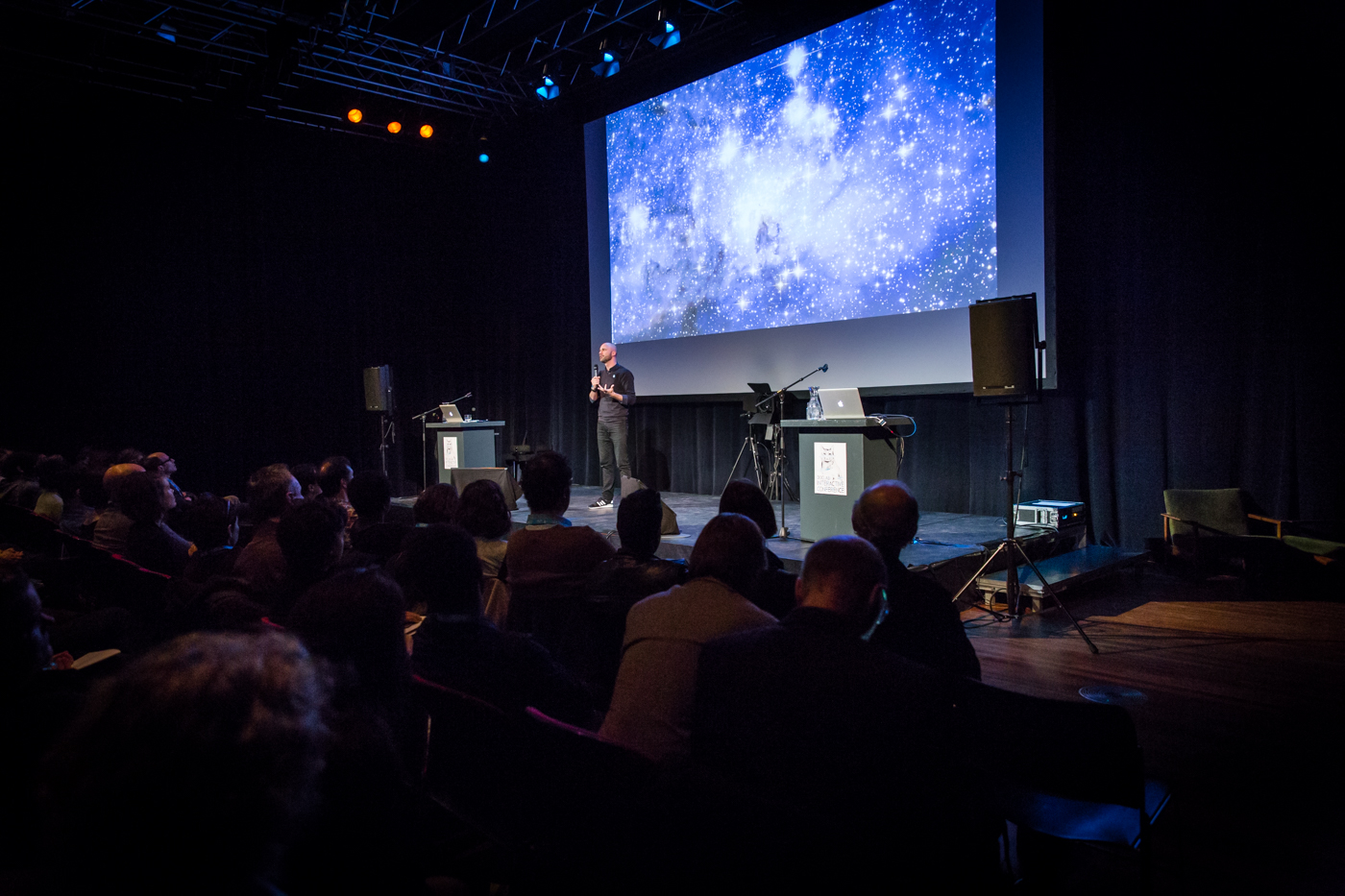

The audience of the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Just like last year, the conference took place at De Brakke Grond (the Flemish Cultural Center in Amsterdam), had an amazing line-up and sold out almost immediately.

I was expecting a same old same old feeling, thinking that there’s only so much you can do with virtual reality but i was wrong. Story tellers using VR and other new technologies learn very fast from their mistakes and have established by now that simply applying what worked in video onto VR isn’t going to cut the mustard. For a star, as Jessica Brillhart said in her opening keynote, “there is no frame in VR.”

But what the event demonstrated once again is that VR is on a thrilling and promising track when it’s left in the hands of story tellers who want to “populate VR world with something else than porn and games”, as Gabo Arora neatly put it.

Something that i should add is that the DocLab: Interactive Conference doesn’t lazily celebrate White Male Supremacy and that’s a rare feast in the tech & creativity world. I didn’t count but at least half of the speakers were women and a fair number of the people who took the stage were people of colour (what’s the PC way to say it nowadays?)

But back to the content! The conference is a super intense 7 hour marathon where i’m getting hit in the face non stop by ideas, images and concepts that i wasn’t expecting. My notes below are going to highlight only the moments i found most interesting. I’m also not following the order in which the speakers came on stage. But it’s not total freestyling either, it’s more of a infantile ‘let’s start with what really got me really REALLY excited’:

Thomas Wallner at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Thomas Wallner always gives a smart, entertaining presentation. Last year, he talked about the pitfalls of using VR to replicate classic cinematographic experience. This year, he showed us how he used a balloon to propel a camera on the upper stratosphere and make the highest ever 360 degree shot.

His company, Deep Inc has also just released together with ARTE an app for broadcasters to help them distribute 360 degree film to their audiences.

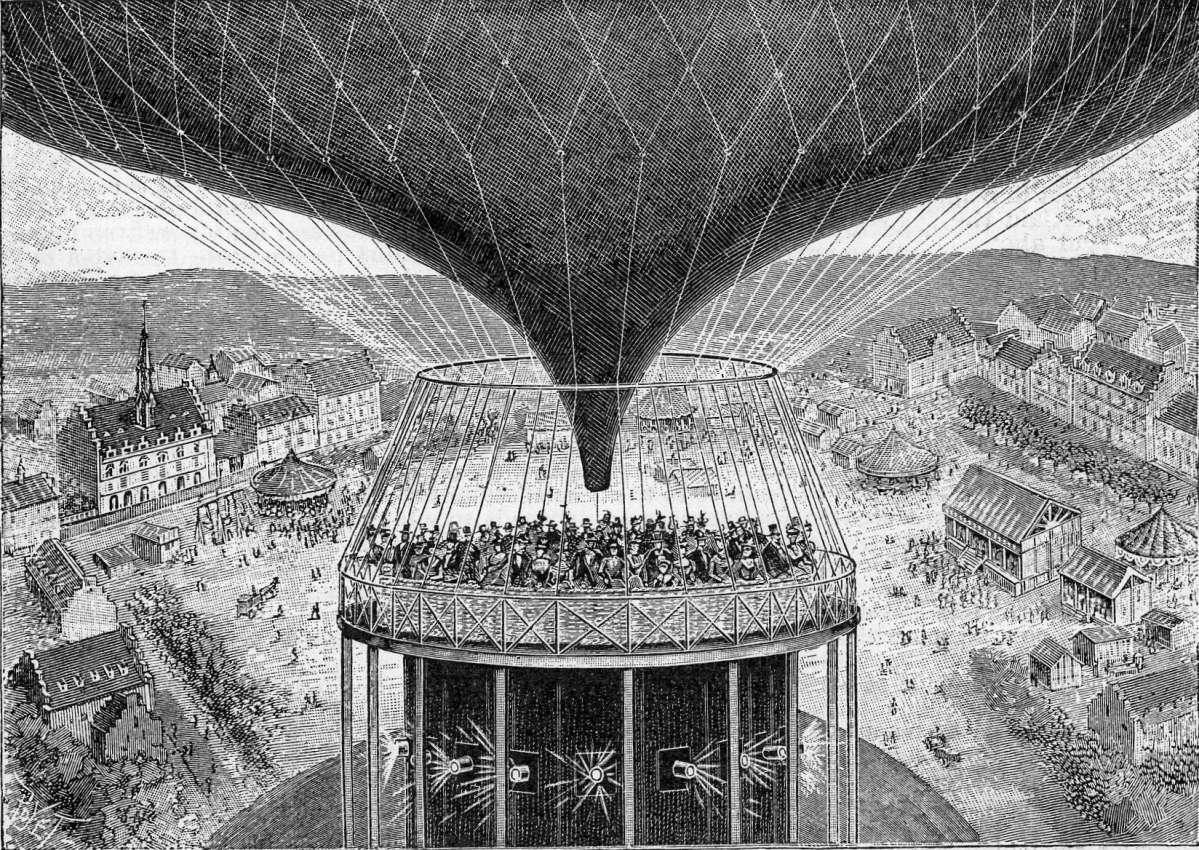

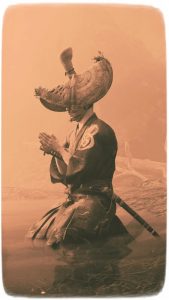

Illustration of the Cineorama balloon simulation, at the 1900 Paris Exposition

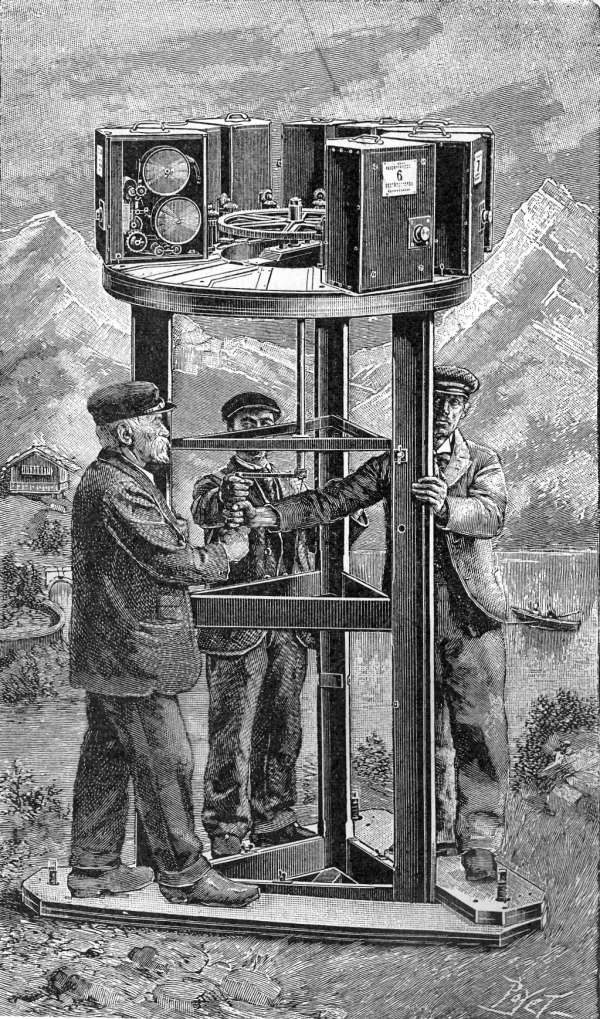

Illustration of the camera mechanism for the Cineorama balloon simulation, 1900 Paris Exposition

Wallner also introduced us to the ancestor of VR. It seems that the first patent for a cinema that surrounds viewers with moving images dates back to 1897. The Cineorama, as it was called, premiered at the 1900 Paris Exposition, where ten synchronized projectors projected onto ten screens arranged in a 360° circle. In the center, a large viewing platform shaped like a hot air balloon. The film simulated a ride in a hot air balloon over Paris. Cineorama closed after only three days for safety reasons, due to the extreme heat from the projectors’ lights.

Ross Goodwin at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Ross Goodwin is a creative technologist whose work explores how artificial intelligence can augment creativity and push storytelling further. Goodwin thinks that nowadays artificial intelligence is as much a design problem as a computational one. Artificial is not perfect, it can be a bit glitchy but so are we as humans. Besides, the type of mistakes that machines make are very different from the ones that humans makes.

Asking if a machines can think is like asking if a submarine can swim.

While on stage, the artist demoed word.camera, a talking surveillance camera that can zoom on a person’s face in the crowd, ‘read’ it and say out loud what it “sees.”

Once the camera is in the room, it is impossible to ignore its presence like we would do with the CCTV we got so accustomed to. This experiment in how machines “perceive” humans is both creepy and playful. On the one hand, it hints at a very near future when surveillance systems will be paired with artificial intelligence and watch over us with penetrating but unpredictable eyes. On the other hand, its glitches and social awkwardness highlight the limitations of technology.

Karim Ben Khelifa at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Karim Ben Khelifa, The Enemy at the DocLab exhibition in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Karim Ben Khelifa, an award-winning photojournalist who has covered conflicts in the Middle East talked about his work The Enemy and his experience as an artist-in-residence at the Open Documentary Lab at the MIT in Cambridge.

After working for 18 years as a war correspondent, Ben Khelifa got frustrated with photography. He felt that, instead of making an impact on the real world, his photos didn’t seem to make any difference. So he started to investigate how VR could be used to give more power to his images, raise compassion in viewers and create new experiences because…

We make sense of the world through stories but remember it by experiences

I’ll talk about the result of his research at MIT, The Enemy, in my next post which will look at the works exhibited in the DocLab exhibition. But in a nutshell, The Enemy is an immersive installation which brings face to face combatants from opposite sides. Wearing the VR goggles, you feel like you’re in the room with them and get to witness what they have to say about their dreams, motivations and who they are. The artist is still working on the installation, planning to use artificial intelligence and the latest technologies in virtual reality in order to make it multi-users. He also wants to eventually send the work back to the fighters.

Angelo Vermeulen at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Angelo Vermeulen, Seeker

Angelo Vermeulen, Seeker

Angelo Vermeulen‘s work is about what he calls ‘entangled reality’ rather than virtual reality. During his talk, he told us about works that involve recycling e-waste to make hybrid art installations, Mars simulation in Hawaii to study the effects of long-term isolation over group dynamics, and using art as a vehicle to explore the world.

Vermeulen is getting increasingly interested in co-creation process. In 2012, he launched Seeker, a DIY spaceship model which people are invited to co-create by experimenting with technological, ecological and social systems that enable long-term survival on board. The project uses spaceship as a metaphor for reinventing the entire world. Seeker is touring around the world and each time, a new crew is invited to use, abuse, hack and transform the previous model of Seeker spaceship.

The Hive Mind at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

The Hive Mind at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Loren Carpenter Experiment at SIGGRAPH ’91 (video Zachary Murray)

At lunch, the crowd was invited to take part in a Breakout game experiment. Everyone grabbed the ping pong paddle that had been left under their seat as the video game appeared on the screen. By flipping their paddle to the red or the green side, people could direct the white dot bouncing up and down on the screen. But your paddle only counts for one vote in the game and you need to be in the majority of green or red to see the dot following the direction you had chosen.

The game was inspired by Rachel and Loren Carpenter‘s 1991 experiment at Siggraph where the crowd similarly collaborated on a game of Pong.

Michelle Kasprzak at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

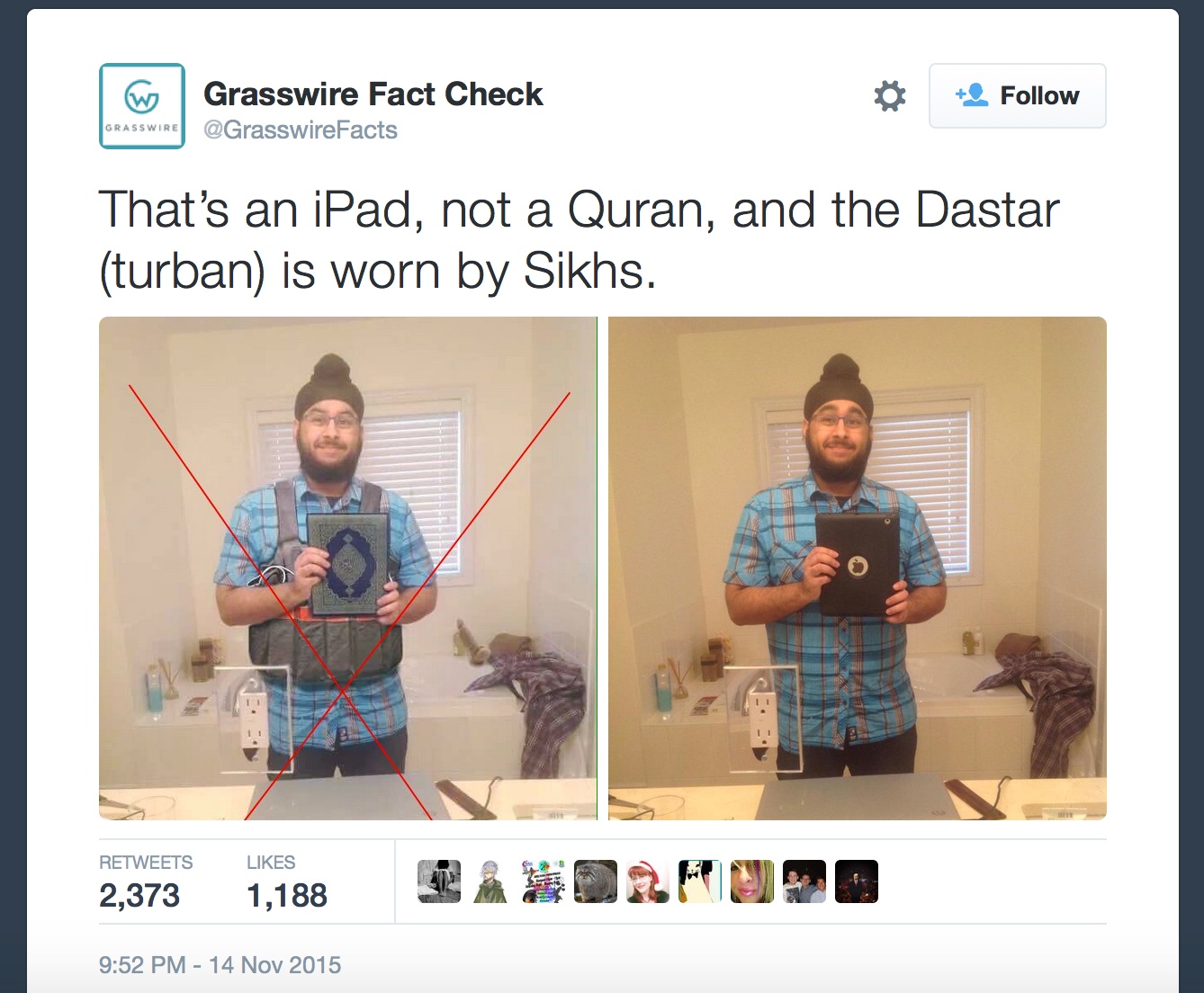

Elaborating upon the Hive Mind experiment, curator Michelle Kasprzak looked at hive mind behaviour online and how online technologies can be sources of good (by giving a voice to minorities for example) or the origin of ruined lives, harmful hoaxes, misunderstanding and hatred. Kasprzak gave several examples of how photos, games and behaviours can be misinterpreted, used to deceive and get out of hands.

A good example of misunderstanding that spreads fast and furious are the photos published in the press that show refugees from Syria clutching their smartphone. Some people reacted by claiming that this was proof that the refugees aren’t poor and don’t need any help. In reality, smartphones are a lifeline for people who’ve lost everything, are far away from their home and still want to connect with their loved ones or simply know in which direction they should walk.

Kasprzak also talked about an online craze called swatting. I had never heard of that one before. It’s the kind of very awful, very stupid joke that i like. Swatting consists in reporting fake hostage situations, shootings and other violent crimes so that an emergency response is dispatched to the house of another gamer. The name comes from SWAT teams, police units in the U.S. that use specialized or military equipment and tactics.

A third example given by Kasprzak involves Veerender Jubbal, a Canadian Sikh man who posted a selfie on 5 August of this year. He was holding an iPad and getting ready for a date. The photograph was photoshopped to add a vest with wires around his torso and the ipad became a copy of the Quran. He was then ‘identified’ including by major press outlets as being one of the terrorists responsible for the Paris attacks.

As Kasprzak concluded, technologies such as surveillance and VR have been on the horizon for a number of years but they are only starting to show their potential now.

Liv Schneider at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Designer and self-defined investigative librarian Liv Schneider has built 3 museums this year! Mostly virtual ones but they are pretty interesting.

Released for Google Cardboard, The Museum of Stolen Art is a virtual space for pieces reported stolen in FBI and Interpol art crime databases. The goals of the museum are to give visibility to art that is otherwise impossible to see on a museum wall, and also to familiarize the public with stolen items in order to assist in the their recovery. Another goal is to bring attention to the subject of cultural theft, especially as a result of war and conflict.

She believes that VR has the power to retain objects and experiences that would otherwise be lost, dissolved or inaccessible to the broader public. Schneider also collaborated with Laura Chen to develop RecoVR: Mosul, a Collective Reconstruction, a VR environment that used crowd-sourced imagery to bring back the historical statues and artefacts destroyed by ISIS when they raided the Mosul Museum last year.

Jason Spingarn Koff interviews Errol Morris at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Errol Morris at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Filmmaker and journalist Jason Spingarn Koff interviewed award-winning film director Errol Morris on stage. Morris has made a number of tremendously interesting documentaries. The two that were directly mentioned during the conference were The Thin Blue Line and Standard Operating Procedure.

Released in 1988, The Thin Blue Line, has a real, social impact on the life of its main protagonist, Randall Dale Adams, a man sentenced to life in prison for a murder he did not commit. Prior to directing the film, Morris worked as a private detective (which might explains why he declared during the conversation at DocLab that he considers “life as a crime scene.”) The evidence that his investigation gathered and presented in the film had a significant impact on obtaining Adams’ acquittal approximately a year after the film’s release.

The other film mentioned is Standard Operating Procedure, a 2008 documentary film which explores the meaning of the photographs taken by U.S. military police at the Abu Ghraib prison in 2003. One of the things that the film attempted to demonstrate is that a photo is only a piece of reality taken out of its context. Morris admitted being puzzled by VR but he also believes that VR has the power to show the context, to work from several angles and display a larger part of the reality that is relevant to a photo.

Morris is not only an award-winning documentary maker, he is also an inventor. He created a system called Interrotron that used a curtain and a teleprompter-like device that gives the illusion that the person on the screen is looking directly both at Morris and at the camera, giving the viewer the feeling that the interviewee is talking right to them.

William Uricchio from MIT Open Documentary Lab at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

In his work at the MIT Open Documentary Lab, William Uricchio looks at the spaces where journalism and documentary cross. Both are reality-based but while journalism is embedded into society and even has a specific political place, we tend to think of documentary in terms of films. If one wants to caricature, he said, journalism is about facts and documentary about truth. Journalism is often limited by these facts. It is also more conservative in its use of technology. Journalism uses the internet as a place to put words. On the other hand, documentary has been experimenting for years with technology and new forms of storytelling and is emphatically ahead of the curve. Even though some newspapers such as The Guardian and The New York Times try to innovate and work with documentary makers. Documentary needs journalism as well because newspapers have the larger audience.

Uricchio identified key conditions to make interactive documentary and journalism intersect:

– cross platforms by collaborating with like-minded organisations specialized in audio, video, documentary or journalism,

– allow the story to drive the form. Some stories benefit from being told using a linear structure. Others need more experimentation,

– experiment and learn. We are at an experimental stage and we’re probably not going to see standardization settle in (like we saw with television) and we will stay in this revolutionary phase,

– avoid pouring over the logic of massmedia,

– welcome dialogue. One thing that documentary does very well is shape conversation and that dimension is very important now that audiences can talk back.

More details can be found in the MIT Open Documentary Lab report that maps the convergence between interactive and participatory documentary practices and digital journalism. This way!

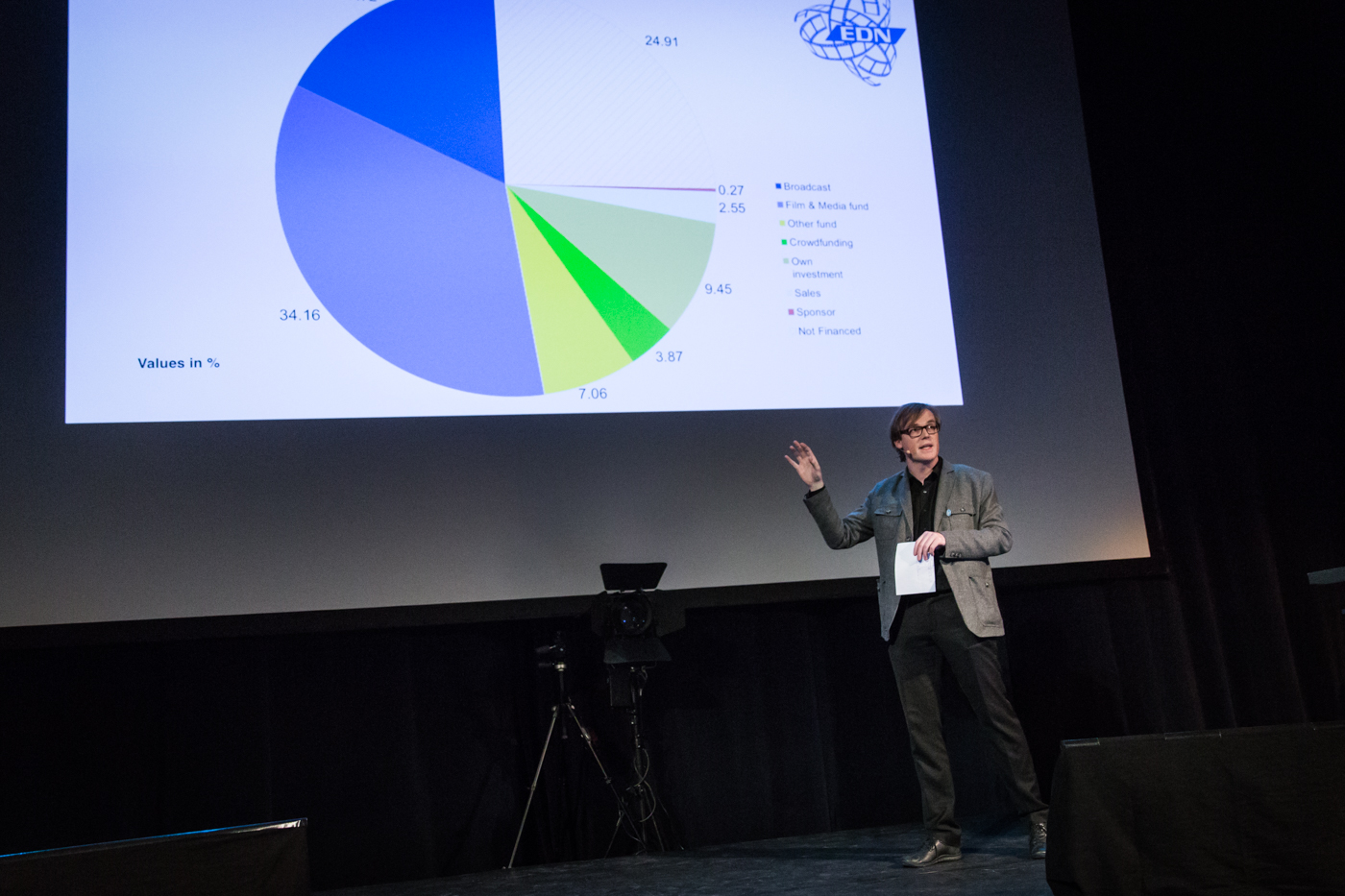

Ove Rishøj Jensen presents the results of a survey about the financial background and expenses of projects that have been selected by DocLab over the years. Photo Nichon Glerum

Uricchio was then joined on stage by conference moderator Ove Rishøj Jensen from the European Documentary Network to discuss the results of a survey conducted by EDN with DocLab about business model of the projects selected for the DocLab competition over the past 3 years. They received usable answers from 17 of these projects. The conclusions are that:

– the makers are investing a lot to develop projects that are not generating much sales.

– either you manage to get good funding, or you work for free. There doesn’t seem to be any middle ground.

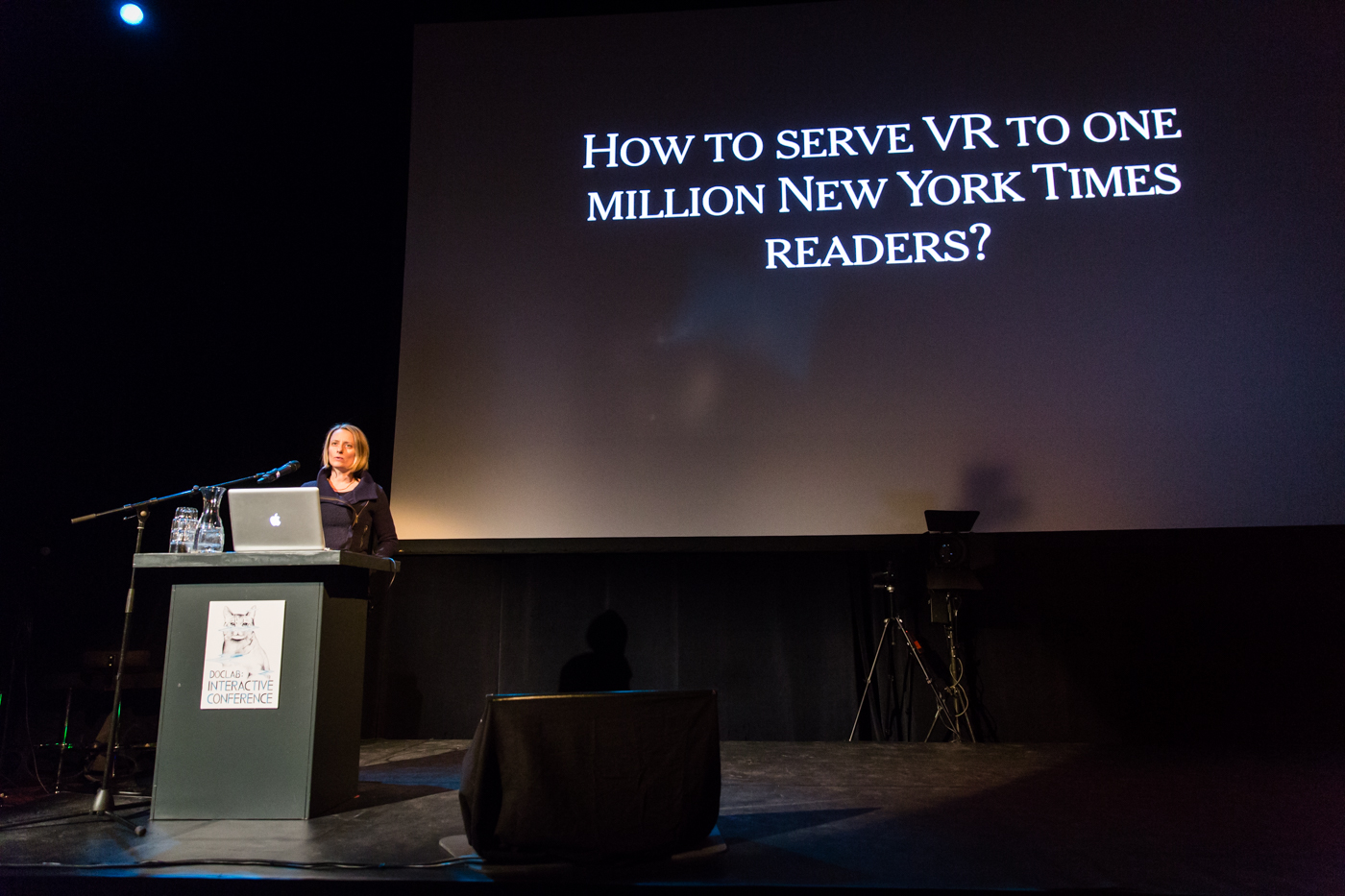

Kathleen Lingo at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Kathleen Lingo talked about NYTVR, the New York Times’s venture into bringing VR to 1 million people. The publication sent a pair of VR cardboard glasses to 1 million of their subscribers and are now regularly adding content onto their op-docs platform. Lingo believes that the platform has so far been a success and that VR can speak to the larger human experience.

Future Predictions panel with Loc Dao, Kat Cizek, Marianne Levy-Leblond and Kyle McDonald at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

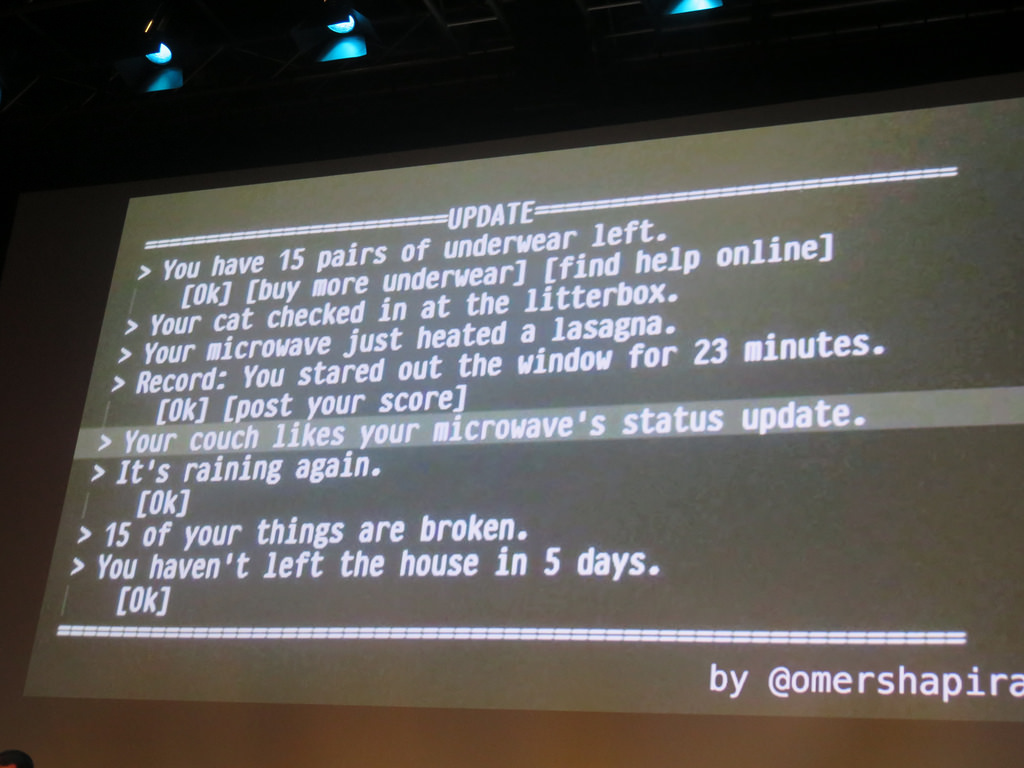

Towards the end of the day, Loc Dao, Kat Cizek, Marianne Levy-Leblond and Kyle McDonald were gathered on stage for a Future Predictions panel. Each of them had one minute to tell us one thing that is likely to happen in the future. Kyle McDonald showed this slide that hinted at how complicated our devices’ interactions with each other and with us might become one day:

Kyle McDonald’s slide (with credit to Omer Shapira)

Reem Haddad and Dima Shaibani present Life on Hold at the DocLab Conference in de Brakke Grond (part of the IDFA International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.) Photo Nichon Glerum

Life on Hold- Haifa Promo

The last talk i would like to mention is the one by Reem Haddad and Dima Shaibani from Al Jazeera. The duo presented Life on Hold, an interactive web doc that travels to Lebanon to uncover the lives and struggles of Syrian refugees. The work tells the story of 10 people, from a 7 year old to a 70 year old. It’s not about information and facts but about empathy, about connecting visitors with the characters and make them see that beyond the label ‘refugees’ there are regular people like you and i. That’s something that gets a bit lost in strategy and politics.

The webdoc features A Wall of Memory that invite visitors of Life on Hold to leave a note for the refugees. Surprisingly, none of them were hateful (as it often happens online.)

The website received many visits from North Africa and the Middle East but people from these parts of the world left very few comments. It seems that web users there are more used to consume media than to actively participate in debates online. But maybe their silence is also due to the fact that the content was optimized for laptop and not mobile phones (most users in the Middle East access media through their mobile phone.)

Veerle Devreese from De Brakke Grond and Caspar Sonnen from DocLab, closing the event

Previously: Sheriff Software: the games that allow you to play traffic cop for real, My notes from DocLab: Interactive Conference 2014.

![7 art and tech ideas I discovered at Meta.Morf 2024 – [up]Loaded Bodies 7 art and tech ideas I discovered at Meta.Morf 2024 – [up]Loaded Bodies](https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/53705969154_73dfdfea6f_c-300x200.jpeg)