Marcos Raya, Untitled (family portrait: group), 2005

Marcos Raya, Untitled (family portrait: group), 2005

Exhibitions at the Wellcome Collection are always eventful. I’ve seen sliced brain, freeze-dried brain, dessicated brain, two wax babies heads dissected, tin face masks for WWI soldiers disfigured by explosions and gunshot, i’ve learnt about the history of narcotics, read about a gentleman turned on by dirty maids, etc. Wellcome’s exhibitions are dramatic and engaging but they are also impeccably researched and edifying. I can’t remember having exited one of their shows without being fascinated by the amount of information their curators manage to pack in each room. Except this time.

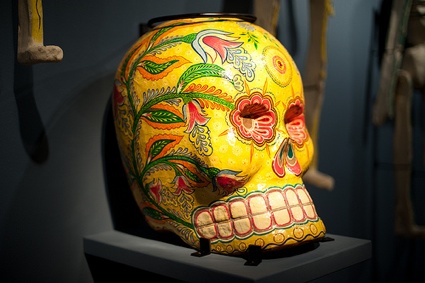

The recently opened exhibition Death: A Self-portrait is entertaining, it contains some fantastic pieces and it definitely deserves a trip to the Euston Road museum but it is a bit light in reflection and cross-disciplinary references compared to what Wellcome has used me to. The show displays some 300 works -most of them being skulls- from Richard Harris‘s collection of cultural artefacts, artworks and scientific specimens devoted to the iconography of death and our complex and contradictory attitudes towards it.

The artefacts are grouped into five themes: “Contemplating Death” (a room full of memento mori), “The Dance of Death” (the ‘many’ faces of death, most of them are actually skelettons), “Violent Death” (artists representing the ravages of wars), “Eros and Thanatos” (the human fascination for death) and “Commemoration” (death, burials, mourning and their rituals). One moment you’re looking at rare prints by Goya, next you find yourself in front of anatomical drawings, puzzling photos in black and white, ancient Incan skulls, or a gigantic chandelier made of 3000 plaster-cast bones.

Otto Dix, Shock Troops Advance Under Gas, from the series Der Krieg (The War), 1924. Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

Otto Dix, Shock Troops Advance Under Gas, from the series Der Krieg (The War), 1924. Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

Otto Dix, Wounded soldier – Autumn 1916, Bapaume, , from the series Der Krieg (The War), 1924

Otto Dix, Wounded soldier – Autumn 1916, Bapaume, , from the series Der Krieg (The War), 1924

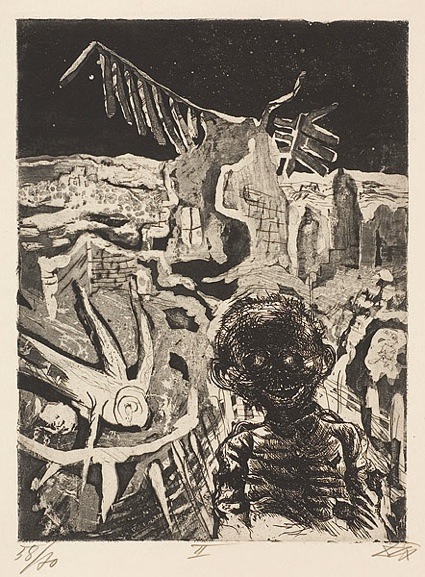

One of the most striking work for me was the truly horrific cycle of 51 prints that Otto Dix made to document his time fighting as a machine-gunner on the Western Front during World War One.

Otto Dix, Night-time encounter with a madman, plate 22 from Der Krieg (The War), 1924

Otto Dix, Night-time encounter with a madman, plate 22 from Der Krieg (The War), 1924

When Shall we Meet Again?, c. 1900. Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

When Shall we Meet Again?, c. 1900. Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

Halloween. Anonymous photo. The Richard Harris Collection

Halloween. Anonymous photo. The Richard Harris Collection

Edward S Curtis, Kwakiutl Man, Crouched, Cradling Mummy, c.1911

Edward S Curtis, Kwakiutl Man, Crouched, Cradling Mummy, c.1911

Linda Connor, Death Dancers, Hemis Monastery, Ladakh, Himalayas, Linda Connor, 2003. Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

Linda Connor, Death Dancers, Hemis Monastery, Ladakh, Himalayas, Linda Connor, 2003. Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

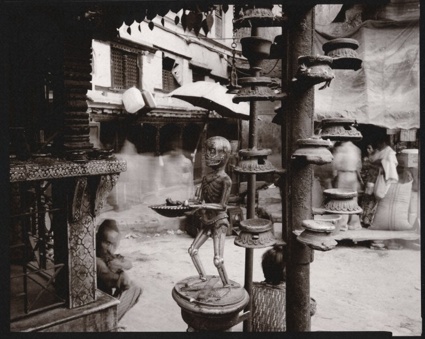

Linda Connor, Skeleton, Shrine, Kathmandu, Nepal, 1980. Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

Linda Connor, Skeleton, Shrine, Kathmandu, Nepal, 1980. Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

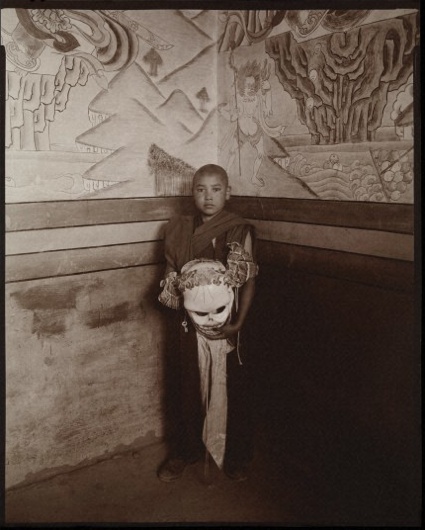

Linda Connor, Young Monk with Death Mask, Ladakh, India, 2003, from Gates of Reconciliation

Linda Connor, Young Monk with Death Mask, Ladakh, India, 2003, from Gates of Reconciliation

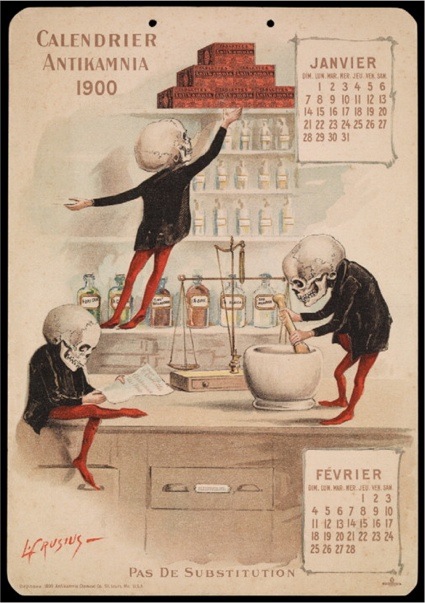

Dr Luis Crucius’s drawings of skeletons animated a promotional calendar distributed to doctors by the US Antikamnia Chemical Company in 1900–01. Ironically, the company’s antikamnia painkillers contained an active ingredient which was later found to be toxic and addictive.

Dr Luis Crucius, Antikamnia Calendars, 1900

Dr Luis Crucius, Antikamnia Calendars, 1900

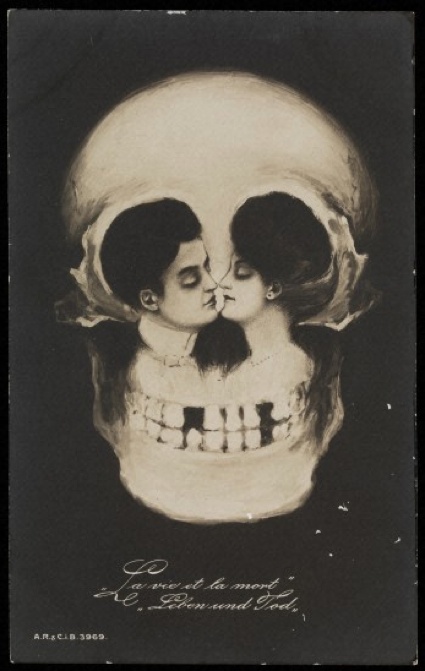

Metamorphic postcard (c1900-10). ‘La vie et la mort, Leben und Tod’ (Life and death, life and death). Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

Metamorphic postcard (c1900-10). ‘La vie et la mort, Leben und Tod’ (Life and death, life and death). Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

Dana Salvo, from the series The Day, the Night and the Dead. Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

Dana Salvo, from the series The Day, the Night and the Dead. Photograph: Wellcome Images/The Richard Harris Collection

Jodie Carey, In the Eyes of Others, 2009. Picture: © Jodie Carey

Jodie Carey, In the Eyes of Others, 2009. Picture: © Jodie Carey

Iturbide, Graciela, Procession. Chalma, Mexico, 1984

Iturbide, Graciela, Procession. Chalma, Mexico, 1984

Our (western) culture tends to keep death in the background. We have lost touch with death and its rituals (unlike, for example, Mexico which celebrates the Día de los Muertos in the most flamboyant fashion.) And since none of us has a direct experience of death, we leave its interpretation and representation to artists.

Marcos Raya, Untitled (family portraits). Photo by Happy Famous Artists

Marcos Raya, Untitled (family portraits). Photo by Happy Famous Artists

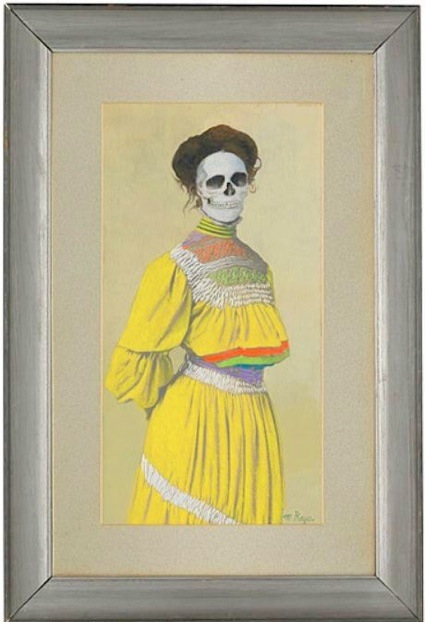

Marcos Raya, Untitled (family portrait: woman in yellow dress), 2005

Marcos Raya, Untitled (family portrait: woman in yellow dress), 2005

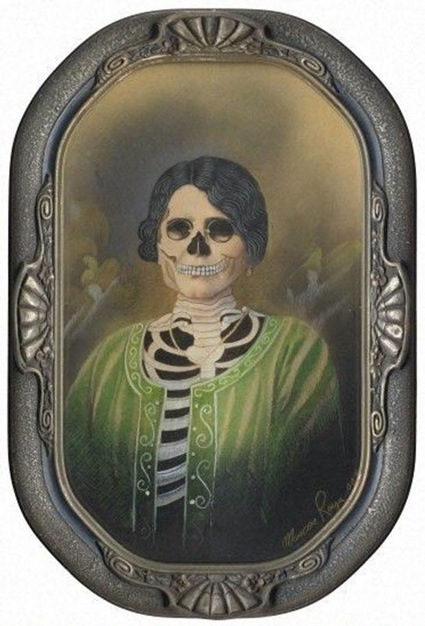

Marcos Raya, Untitled (family portrait: Grandma), 2005

Marcos Raya, Untitled (family portrait: Grandma), 2005

Found Human Skull. Anonymous photo taken in 1927 at the San Diego home of Phebe Clijde. Part of the Richard Harris collection

Found Human Skull. Anonymous photo taken in 1927 at the San Diego home of Phebe Clijde. Part of the Richard Harris collection

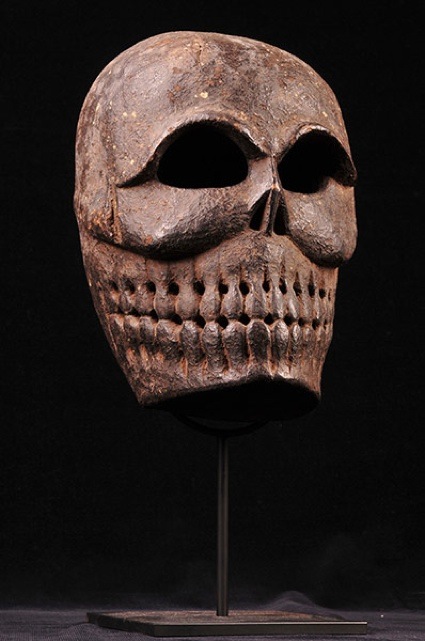

Tibetan carved wooden mask, 19th century

Tibetan carved wooden mask, 19th century

Photos by Happy Famous Artists. The Guardian has a slideshow.

Death: A Self-portrait remain open until 24 February 2013 at the Wellcome Collection in London. Admission is free.

Related: Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men right now at the London Museum, Exquisite Bodies at the Wellcome Collection, Mind Over Matter and Brains: The Mind as Matter.