“How do the Rave-o-lution of 12 March 2018 in front of the Georgian Parliament in Tbilisi and anti-fascist protests in Berlin relate to ancient Dionysian rituals, and why does the soundtrack to these events come from the drums of African Americans? And to what extent does dance club culture reflect the current socio-political situation and the struggle of individuals or of groups?”

Dance of Urgency, exhibition view. Photo Sam Beklik

If ever you find yourself in Vienna this Summer, don’t miss Dance of Urgency, an exhibition at Q21 that looks at dance as a political, social and economic phenomenon. The show was curated by Bogomir Doringer, an artist and curator whose interest in the connections between dance culture, crowds movements and politics stems from his experience of dancing and looking for ways to feel free inside a techno club in Belgrade while NATO was bombing his city in 1999. Perhaps it’s this personal experience that makes the exhibition so compelling, entertaining and thought-provoking. That and the music of course.

The show looks at club culture under all its facets. It opens with examples of underground spaces where young people shape countercultures and ideals that eventually spilled into the streets as protests against reactionary governments. And it closes with a spectacle of the massive (and massively lucrative) electronic music festivals that have become mainstream Summer entertainment.

All it takes to create change sometimes is just one guy:

Derek Sivers, First Follower: Leadership Lessons from Dancing Guy, 2010

Writer Derek Sivers used the viral video of a guy dancing alone at a music festival in the USA to explain How to Start a Movement, in a TED talk. The humorous instructional political video is used as an introduction to the section in the exhibition that explores the connections between dance floors and activism, and how ideas resonate, from the dancing body in public spaces to the outside world.

Jan Beddegenoodts, Ayed, 2018

Jan Beddegenoodts, Sama

Jan Beddegenoodts interviewed by MuseumsQuartierWien for Dance of Urgency

Jan Beddegenoodts‘s short documentaries follow some of the strong creative minds who gave rise to collective cultural movements in their own countries.

NAJA is dedicated to Naja Orashvili, one of the icons of Tbilisi #raveolution and of young Georgians’s yearning for a new, progressive country. The artist and activist is one of the founders of BASSIANI, a queer nightclub which was under threat of closure by the Government until thousands of ravers protested in the streets of Tbilisi and forced the authorities to step back. She is also one of the main figures behind the White Noise movement, a political group founded in 2015 with the objective to decriminalize drugs.

AYED is a portray of Ayed Fadel, a member of Jazar Crew, a movement of young cultural activists dedicated to empowering music and culture in Palestine.

SAMA follows Sama Abdulhadi, a producer, sound artist and DJ who organized the first techno nights in Ramallah. She’s since been touring the globe, giving techno music workshops to kids and raising awareness around the violence of the Israeli occupation of Palestine (sometimes by introducing the issue shrewdly into her work but mostly because her interviewers keep on asking her about it.)

Dan Halter, Zimbabwean Queen of Rave, 2005

Dan Halter, Zimbabwean Queen of Rave, 2005

Opponents of the apartheid in South Africa used music and dance to make their voice heard and motivate fellow demonstrators to keep protesting against discrimination and segregation. Dan Halter’s video uses archive material to demonstrates one of the activists tactics: a war dance called toyi-toyi. Characterised by its rhythmic, stomping movements, it was used in political protests in South Africa during the Apartheid. As one activist puts it, “The toyi-toyi was our weapon. We did not have the technology of warfare, the tear gas and tanks, but we had this weapon.” After the Apartheid, people in South Africa kept on using toyi-toyi to express their grievances against current government policies.

The images of mass protest are mixed with archives showing the white young people of 90s rave culture dancing carelessly in public spaces.

The soundtrack of these images is Rozalla’s 1991 hit single Everybody’s Free (To Feel Good). The Zimbabwean electronic music performer became known as ‘The Queen of Rave’. No matter their skin colour and cultural experiences, people danced to her music at the time and understood its call for freedom.

Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Himey, Documenting Cxema (still from the film)

Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Himey, Documenting Cxema (extracts from the film). Music by Stanislav Tolkachev

Initiated by DJ Slava Lepsheev after the EuroMaidan revolution in which almost 100 citizens were killed by the police while demonstrating against the government, Cxema is the biggest rave event in Ukraine. The 2014 uprising has left a mark on youth culture. “The Euromaidan brought people together and created a community, but once it finished we wanted to continue that,” explained one of the organisers in an interview. “This is what CXEMA is about. The rave is political even if people don’t realise it themselves, it’s about community”.

Cxema offered a space for its participants to shape Kiev’s post-revolution identity. And even the less politically-active among them could dance and experience moments of normality, togetherness and freedom in a country where their future looks chaotic.

Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Himey, created an hypnotising movie that attempts to reflect on the atmosphere of Cxema, from swarms of individuals dancing in unison to the moment when they exit one by one and go back to the the light of the sun and the daily grind.

Events like Cxema move from illegal to semi-legal venues. Many of them abandoned spaces on the outskirts of the city. The kind of spaces Nikolaus Geyrhalter toured the world to film…

Nikolaus Geyrhalter, Homo Sapiens

Nikolaus Geyrhalter, Homo Sapiens

Nikolaus Geyrhalter, Homo Sapiens

Nikolaus Geyrhalter, Homo Sapiens (trailer)

Geyrhalter’s Homo Sapiens films features train stations, shopping malls, hospitals, amusement parks, power plants, schools, churches, whole streets, monuments and other ruins of our industrial age devoid of any human presence. These are the kind of locations that get invaded for one night or longer by ravers. Their choices don’t go unnoticed. Nowadays, cities are following the moves of club culture and other rituals of gathering as they see them as key parts of urban regeneration projects. In Amsterdam, for example, new temporary clubs are often harbingers of gentrification.

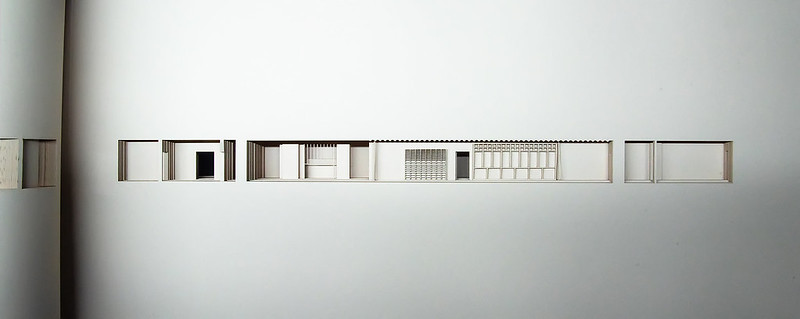

Francesco Pusterla, in collaboration with Dimitri Hegemann, commissioned by Bogomir Doringer, Tresor – Berlin 325 Longitudinal Sections, 2019

Francesco Pusterla, in collaboration with Dimitri Hegemann, commissioned by Bogomir Doringer, Tresor – Berlin 325 Longitudinal Sections, 2019

The Tresor club in Berlin is an iconic example of an industrial ruin that became a cultural space. Inaugurated in 1991, the club played an important role in uniting German youth after the fall of the Berlin Wall. It served as an experimental space where new relationships were established through collective dances to the sound of electronic music. Music without words, with repetitive beats, united people and healed unspoken traumas.

Tresor closed its initial location on 16 April 2005, after several years’ prolonged short-term rent. The city sold the land to an investor group to build offices.

The original architecture of the legendary techno club has been reconstructed as a laser-cut book sculpture produced by architect Francesco Pusterla with the help of Dimitri Hegemann, the owner of the Tresor club.

Anne de Vries, Critical Mass: Pure Immanence, 2015

The extravagant displays of lights and artificiality pictured in Anne de Vries’ video Critical Mass: Pure Immanence shows another, more commercial side of techno culture. One that has been politically sanitised and rebranded subculture as a lucrative entertainment. The work highlights how far some techno events are from the 1970s electronic music values that came from an urgency to empower and unite its small (often queer) and alternative communities. Current electronic dance music events, in particular the ones dedicated to the genre known as Hardstyle, can reach grandiose proportions, with spectacular audio-visual productions mounted by promotional companies. In the film, swarms of tens of thousands of bodies in concert locations are filmed with the zoom-in and zoom-out of a sporting event cam.

The voice-over of a text inspired by the 1995 essay Pure Immanence by Gilles Deleuze accompanies the film and comments on the philosophical dimension of crowd-based experience. The film is as overpowering as the experiences it depicts. It demonstrates the power of the music industry’s spectacle and its potential to alter states of consciousness and control crowds.

More works and views of the show:

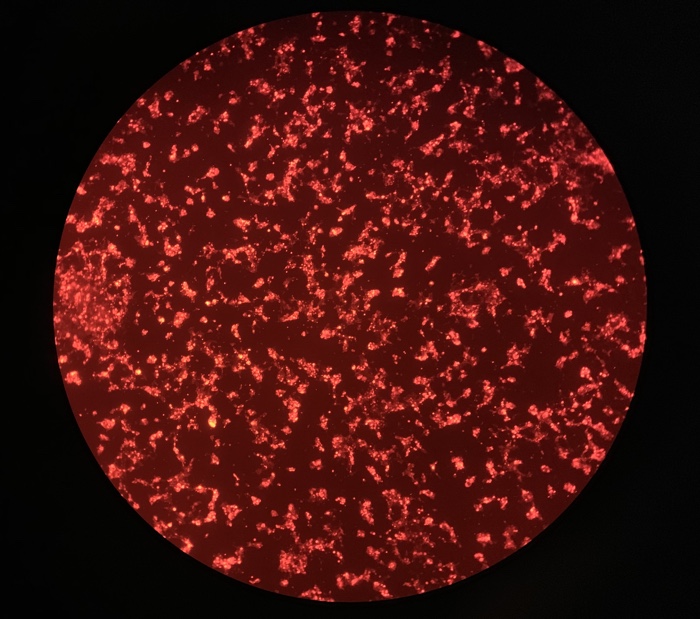

Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Lovesick. The Transfection

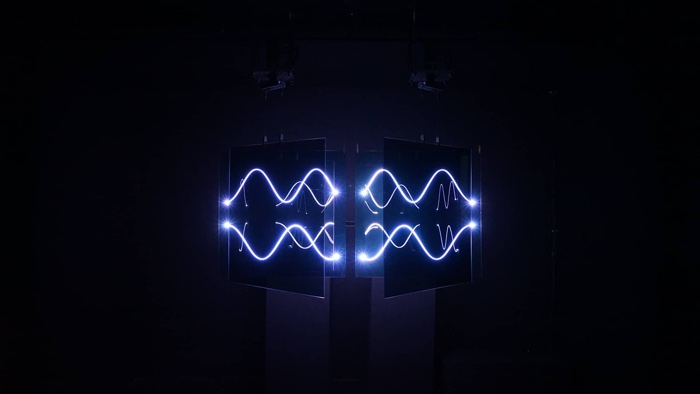

Shohei Fujimoto, Power of one Surface

Dance of Urgency, exhibition view. Photo Sam Beklik

Dance of Urgency, exhibition view. Photo Sam Beklik

Dance of Urgency, exhibition view. Photo Sam Beklik

Sampo Hänninen, Empiric Study Panorama Bar

Dance of Urgency, curated by Bogomir Doringer, remains open until 1 September 2019 at frei_raum Q21 exhibition space MuseumsQuartier Wien in Vienna.

Participants of the exhibition have contributed their favorite tracks to Dance of Urgency playlist!