Caps Lock – How Capitalism Took Hold of Graphic Design, and how to Escape from it. Author: designer and researcher Ruben Pater. Publisher: Valiz.

Ruben Pater‘s The Politics of Design. A (Not So) Global Manual for Visual Communication is still, 6 years after its publication, one of the few books I keep recommending and offering as a present again and again. Caps Lock is equally sharp, visual and keenly attentive to socio-cultural contexts.

Caps Lock tells the long story of the intertwined relationship between graphic design and capitalism. Looking back at history, sharing practical examples, explaining key movements and concepts but also detailing a vision of graphic design practice that would emerge outside of this often uneasy alliance with capitalism, the book offers the kind of uplifting read I desperately need right now. I’d recommend it to everyone who loves design, everyone who is tired of design and everyone who has heard too often that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.”

Ruben Pater identifies 12 roles that designers play in relation to capitalism. These roles are distributed into 3 main sections:

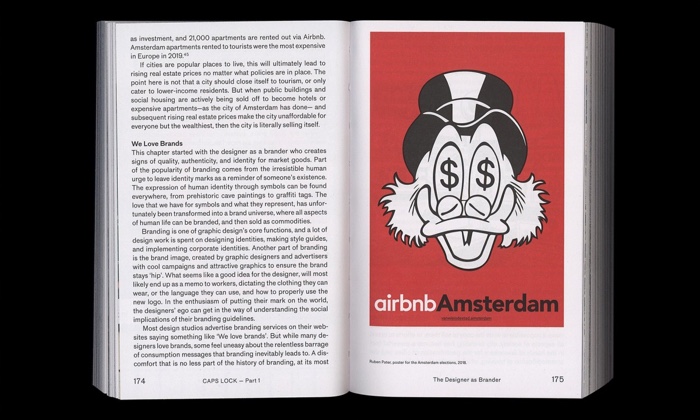

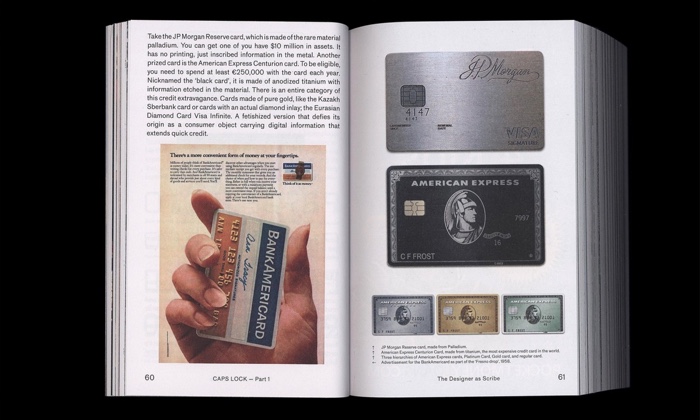

The first part looks at how the work of graphic designers serves capitalism. The designer as scribe can be traced back to earlier times, when scribes and clerks kept financial records, designed coins and banknotes, created graphic notations, etc. Today’s scribes use software but they still have the same mission: instilling trust in the financial system. The designer as engineer brings order to markets with graphic documents such as forms, contracts, passports, maps, infographics, shipping containers, barcodes, etc. These documents go through a process of standardisation that facilitates colonial expansion, control of movements, outsourcing and, more generally, the functioning of international markets across vast distances. The designer as a brander and a salesperson works towards the commodification of all parts of society. They create brands, logos, ads, corporation identities and interfaces.

The second part of the book shifts the focus from what designers make to how they work. The section dissects the culture of exploitation behind the glamour of design. The chapters on the designer as worker and as an entrepreneur offer the picture of a job loaded with burnouts, unpaid internship, precarity, privileges, mental health issues, exploitation of freelancers, etc. These 2 chapters also suggest possible alternatives to toxic work conditions that platforms like fiverr normalises and amplifies. The designer as amateur reminds us that the majority of design in the world is done by people who do not call themselves design and whose creativity is therefore not even acknowledged. The designer as educator details how education prepares designers to work in capitalist conditions. It questions how knowledge is produced, shared and commodified but it also presents some of the alternatives that challenge the view of design education as a costly and privatised factory that churns out design workers.

.

Dennis de Bel and Roel Roscam Abbing, Packet Radio

The third part looks at strategies within design that challenge capitalism. The section opens on the designer as hacker to detail how hackers’ ethics can inspire designers to use technology not for profit but for the benefit of society. Starting with tools and platforms that respect users’ freedoms and community. The designer as futurist, usually an adept of speculative design and/or design fiction, looks to improve society by thinking beyond what is currently feasible. That same strategy is increasingly being co-opted by consultants and trend watchers to provide multinationals with ideas for new products, services and markets. Speculative design and design fiction still have an important role to play when it comes to imagining societies with fewer products and with social relations that are driven by inclusiveness, intergenerational thinking and respect for all cultures. The designer as philanthropist uses their skills to help others. With the risk that a good intention ends up amplifying the power of capitalism and keeping inequality in place. The designer as activist plays a meaningful role in society when they donate time and resources while challenging the power structures in place. Otherwise it runs the risk of falling into the “cause washing” trap.

To illustrate what design outside of capitalism can really achieve, Pater portrays 6 design collectives whose practice is not just ethical, it also aims to give designers decent salaries and labour rights through various strategies that go from local development funds to micro-donations, from grants to commissions, etc.

In order of appearance in the book:

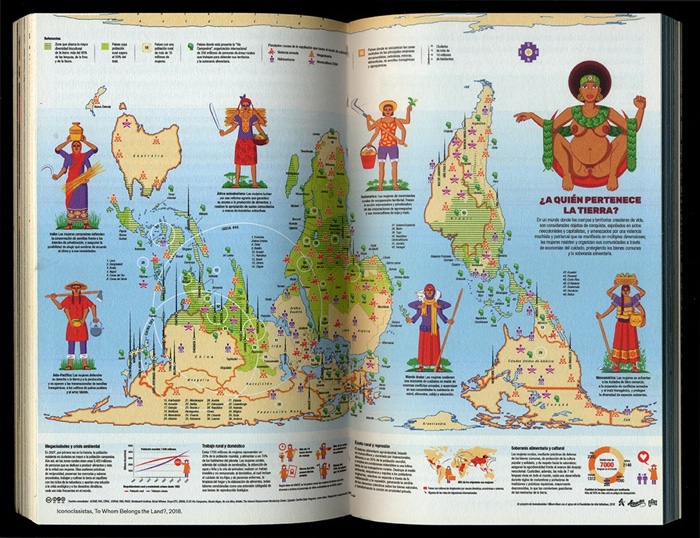

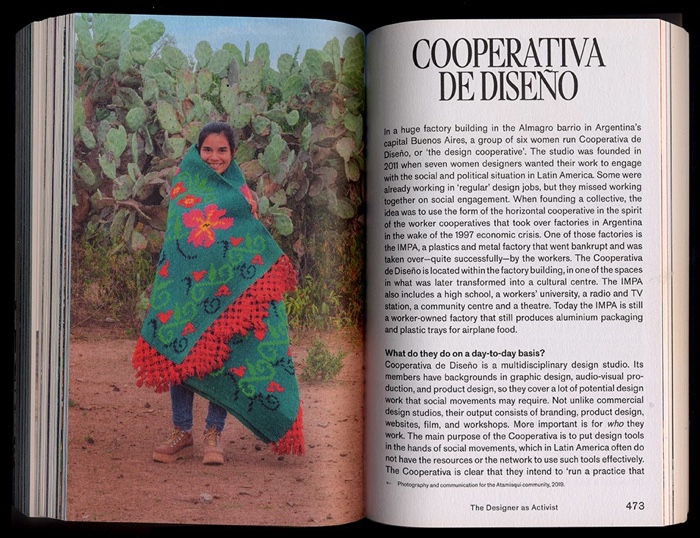

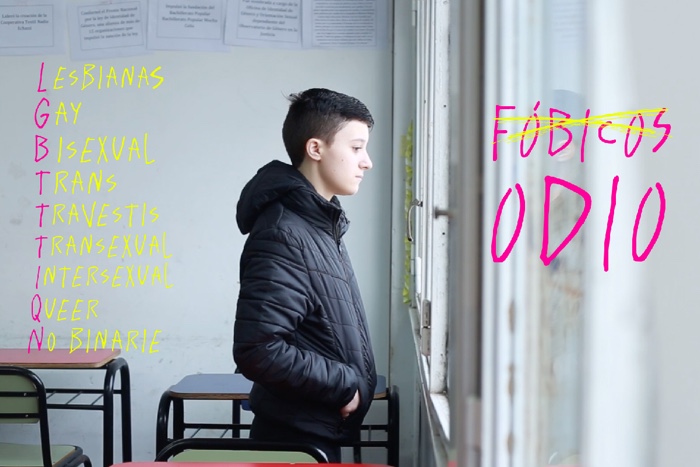

Italian design studio Brave New Alps whose locally-rooted practice involves a community academy at a local train station, sparkling drinks projects, a Precarity Pilot website to help designers set up alternative practices, etc. Common Knowledge, a workers coop from the UK that explores how digital tools can support activists organisations and radical politics. Cooperativa de diseño, a Buenos Aires-based design cooperative run by women who want to put design tools in the hands of social movements. The journalists, filmmakers and designers of Midia Ninja (an acronym for Independent Narratives, Journalism and Action) use social media to cover the stories that Brazil’s main media outlets ignore: they report on indigenous struggles, corruption, climate crisis, deforestation of the Amazon and more. In Brussels, Open Source Publishing creates graphic design works using only FLOSS and offers typefaces, publications, workers’ knowledge and texts free to use, adapt, redistribute. Finally, members of The Public in Toronto identify as POC and/or queer or trans. Their practice blurs the boundaries between designers and non-designers by means of co-creation.

Cooperativa de diseño, Pibxs

What these design studios do is far more than simple pro bono work: they are deeply invested in the communities they work for, they believe in mutual aid principles, in co-creation and in sharing their findings, knowledge and resources. They demonstrate that a shift from competition to care is possible and gratifying.

Previously: Drones, pirates, everyday racism. An interview with graphic designer Ruben Pater, Graphic design for social change, The Politics of Design. A (Not So) Global Manual for Visual Communication, etc.

Image on the homepage: Brave New Alps.