What happens to design when it has to evolve from a world where designers do wonders with (seemingly) unlimited resources and energy to a world where their creativity can only rely on limited ones?

Gauthier Roussilhe interviewing David Gener, a citizen and electrician leading his village towards energy autonomy by 2022 (Prats EnR). Credits: Nicolas Loubet

Gauthier Roussilhe is a designer and researcher working on the effects of the Anthropocene. Which is quite a fashionable issue to specialise in these days. Unfortunately, very few designers today are able to address the urgency of the environmental threat with the thoroughness and the determination required. Roussilhe, however, is one of those rare thinkers and designers.

Roussilhe has spent the past couple of years wondering how his discipline could become a meaningful and positive actor in the fight against climate change. He believes in implementing systemic changes, not in ‘saving the world’ with reusable coffee cups, paper straws and other interesting but ultimately secondary gestures.

There are several reasons why I found his work important. First, Roussilhe puts the non-human (animals, plants, natural resources) back into the design reflection. Second, he is keen on sharing his research and reasoning with the next generation of designers but also with public institutions, local councillors, NGOs, private organisations, think tanks and lobbies striving to mitigate the effects of climate change on the planet and on society.

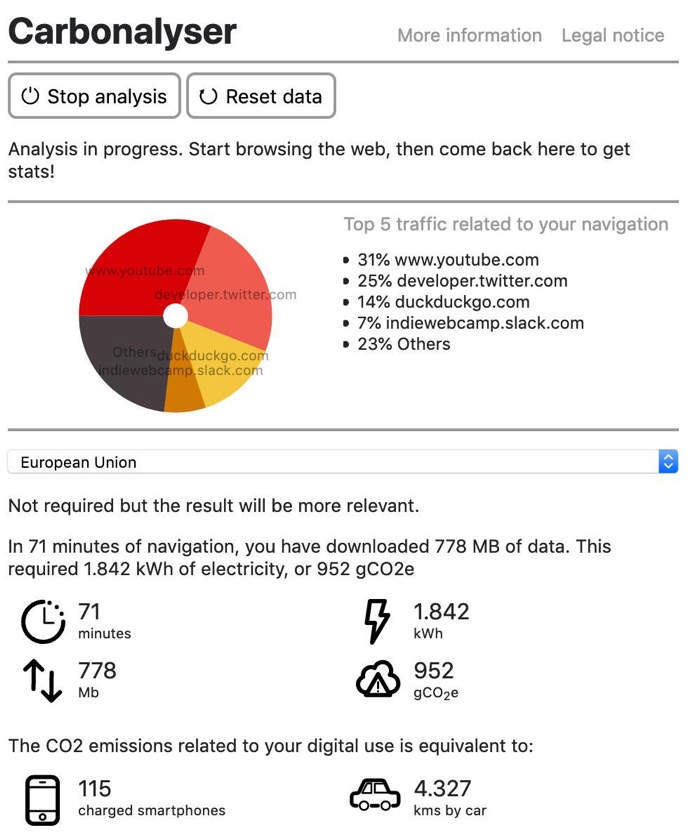

Finally, i found his approach to digital technology worth sharing. He released an eye-opening digital guide to low tech, he leads workshops with UX designers, asking them to design a website with an limited energy budget rather than a monetary budget and together with French think-tank The Shift Project, he recently worked on a report that details and visualises the unsustainable use of online video services.

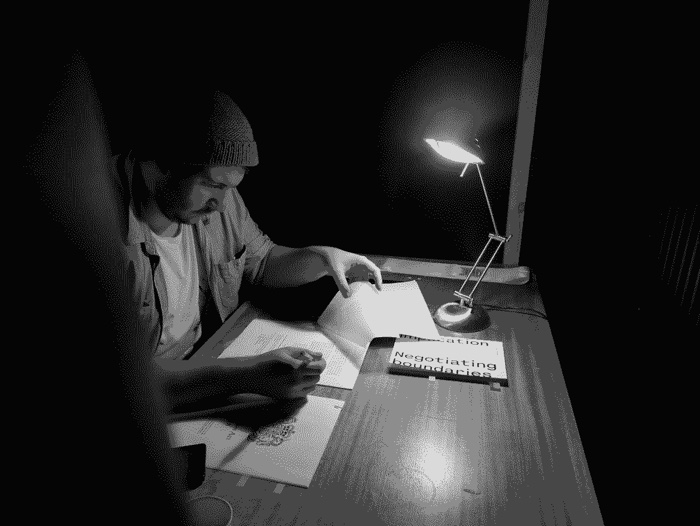

Gauthier Roussilhe leading a workshop for UX designers in Toulouse, asking them to design a website with an limited energy budget (kWh) rather than a monetary budget (€), credits: FLUPA Toulouse

The designer has been kind enough to answer my many questions over Skype a few weeks ago:

Hi Gauthier! Most designers nowadays are conscious that we need to do something about the ecological emergency. Yet, the idea of a green, sustainable growth made of reusable coffee cups and data centres powered by wind turbines still seems to be the feel-good answer for many designers, businesses and members of the public. What do you think are the main misconceptions around “sustainable design”?

It might be interesting to first go back in time and look at the path that lead me to think about climate change and obviously at the Anthropocene as a framework.

I used to run a small design studio and when i split with my business partner, after 4 or 5 years of collaboration, I started traveling in Europe to shoot a documentary called Ethics for Design. I felt a bit lost and it was a way for me to meet my peers, reflect on the question of design responsibility and turn it into a documentary for other designers who might be asking themselves the same questions as I was. The main take from the documentary for me was that ethics alone means nothing because it’s a vector that leads to politics. Which got me wondering about what kind of critical engagement I should get into. The most urgent thing (not that there’s any hierarchy), the one i felt I could have the most impact on was the the concept of the Anthropocene and the climate emergency. From there, I started to redirect my whole practice towards using this issue as the main framework of my practice.

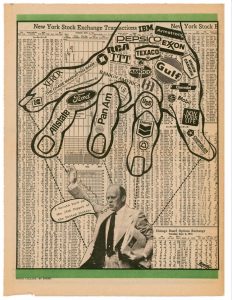

For a long time, I had been wondering why designers were so bad at accomplishing (or even understanding) something regarding this issue. It took me a long time to reflect upon this and I will hopefully publish a research paper on that very topic soon. The paper will be looking at design through economics because I think it is the main lens through which we should look at the design industry. Not that design is anything but economics but we need to see that economics shapes the way that design sees the world.

I’ve pinpointed 3 economic myths that exist within design, first through my own practice and later on through academic research.

First, designers always thought they were working for humans which is completely false. Maybe some design practices have been looking at that but mostly designers are working for an economic persona thought as a rational being, a historical human being that optimises its exchanges to maximise happiness. That’s what is at the heart of design and it’s deeply problematic because the human shouldn’t be at the centre all the time, it should be put back into the ecosystem.

The second economic myth is that design historically appeared within a paradigm of apparently unlimited energy and resources. The rise of the digital industry made it very clear that no matter the experience of the designer, if you ask them “can you design a website for 3 watts an hour?” Nobody can answer that direct question.

The third problem is that designers do not take into account externalities, such as waste, pollution, social issues. They know about it but don’t engage with it. They see it as a failure of the system, not a constituent part of the system. The reason for that is that in neo-classical economic thoughts, you cannot think of externalities as a constituent because it would upset the equilibrium of price and demand. Designers rarely take externalities as the main basis for their work and succeed by doing so.

Because of these three myths, which are mostly associated with Occidental design and very targeted at urban development, and at the social reproduction of Western, capitalistic development more specifically, design as it is practiced today makes no sense regarding the transition because its framework has been influenced by mainstream economic thinking and economic world view.

In consequence, if you look at design through an Anthropocene framework, you have to change everything when it comes to economics. You have to include more than humans, you have to include non-growth economics, you have to shift the regime of property (from private to commons), etc. You have to release a lot of new imaginaries and tools to foster this practice. We are yet to create those.

Gauthier Roussille, Ethics for Design

Do you feel people are getting more conscious about these issues? Are you scaring off the students and other designers you meet? Or do you tap into something they are already concerned with?

In France, I first came in contact with students and professional designers through ethics, that was my entry point into the field. When I was giving conferences or screening the documentary, I was actually pinpointing something that students felt but were not able to express. Even if ethics is part of the curriculum, it’s never enough and professors cannot dwell too much on ethics because they have a pedagogical agenda to follow. Even in the context of continuous training, designers who are already in the professional field are not really talking about ethics, politics, non-occidental word views, they sometimes think about energy and climate within design but they also feel powerless. They don’t have any tools nor do they know how to reframe the ones available in order to work towards the issues that need to be urgently addressed. Since Modernism, design has been mainly thought as a universal practice that can be applied all over the world and that uses the city as its main scale. I come from the countryside so I was already aware of that urban-minded approach. I could see that mainstream design methodologies and tools were neither appropriate nor efficient in rural areas…

Could you give an example of what you mean by that?

For example, my PhD research is based in my village. Over there, it’s completely pointless to say I’m a designer. Nobody knows what it means and nobody cares about designers. If I was actually trying to make some design practice in this village, what title would people give me? Maybe I’d be called “deputy mayor”, that might be the closest thing to designing for them. Is it even important to be called designer as long as you work towards the territory needs and interests? At least, it counters social reproduction of the “designer”.

The fact that we think of digitalising everything makes no sense in specific territories where social links don’t need to be digitalised and people don’t want to depend on technical structures to communicate. Most of the things we have been told in design have been completely challenged in the rural context. Designers have mostly been urban-centred. All their methods and tools have not been very successful when implemented in the countryside, especially if you think about commercial design. You can’t brand a village. You don’t produce standardised digital tools for a village, you can’t erase all the specificities of these territories.

I’m going to play the devil’s advocate. What if i told you that the rural way of life belongs in the past, that it needs to adapt to the changes society is undergoing?

It’s only my hypothesis but I think that people are largely mistaken about how urban and rural areas interconnect with each other. In France, more and more somewhat privileged, well-educated young people, if they have a chance to move, go back to rural areas, only to understand that “ruralilty” as they had thought it doesn’t exist. They are sometimes dragged out of the false binary of rural/urban to have a more precise view of a territory in which they live. Once there, they change their practice. I don’t think rural areas will have to dissolve into urban lifestyles. Quite the opposite. I believe what we call “rural areas” are where changes can happen. Because everything is territory-based there and that’s important.

Cities are becoming increasingly uninhabitable. At least for me. I want to be part of a specific territory. In rural area you can see for yourself what your life depends upon. The city doesn’t show you that.

I’ve started working on a PhD. The first year of the PhD, I will try and answer the question: What does the village depends on? I will work with people in the village who have an amazing amount of skills to collaborate and create a giant cartography that will show what the village depends on. It will be the size of the wall in the municipal council and every political decision should be reflected on this cartography. I need to look at energy, water infrastructure, garbage and waste system, soil production, geology, farming, cultural life, etc. It will be my first exercise of this kind but I want to make it in a way that will make it possible for people to assess it, reproduce it and adapt it to their own territory.

After that, I’ll go to China for another part of the PhD to articulate local and to question possible autarkic views of independence or autonomy in a globalised world. Then I’ll go back to the village again to try and imagine what daily life is when there is less energy, less resources in this very specific context while bridging the historical inhabitants of the village and the newcomers.

Underneath this practice-based research is the need to completely rethink what design is for me. I don’t think that the main function of design nowadays is to produce things. We should however adapt existing systems. I see more value in investigation than in production. I’m now working on a triptych that is investigation, negotiation, production. Production comes as a last step and can only be relevant if the previous step have been performed correctly.

In parallel, I’m organising an Adult Education Scheme in design in Paris. It is a free pedagogical programme that will take place once a month and is aimed at young designers. We are trying to figure out what will be the basis of design education in the framework of the Anthropocene. I’ve lost faith in design education, at least as it is conceived in France, but that’s another story. There will be 10 classes, I’ll give 3 classes that will look at the history and theory of economics in design. I will also cover ethics and cosmopolitics. Others classes will look at energy, techniques and engineering. Furthermore, I will ask other designers to talk about decolonisation, maintenance, etc. Just to set up the main guidelines of a new curriculum for design. It will be free and open to everyone. We’ll document the interventions on videos. They’ll be open source and available online.

You’ve lead workshops with UX designers, asking them to design a website with an limited energy budget (kWh) rather than a monetary budget (€). Your own website is an elegant and striking example of what this means. Apart from lower image resolution, where else can UX designer intervene?

I think people have a very standardised imaginary of what a low-tech website can look like. Mostly because, so far, no brain power has been invested in this area. People are comparing low-tech web design with a practice of design that’s been thriving for the past 20 years on unlimited energy and very limited structural constraints. We cannot compete with that because it was a design produced without any concern for planetary boundaries. But now we should also start investing time and thinking into what low-tech websites should actually look like. We still have a lot to investigate and explore in that area. I’m actually getting a lot of job offers on that very specific topic.

We are now looking at how we can add an map to a website. Usually, when you want to add a map, you just embed Google Map. However, in a scenario where we have limited energy, we have to look for the easiest way to produce a map in a very specific context. You need to pick up the scale of the map so it is consistant with the information the user is looking for. This means that you are not relying on standards anymore. You have to push back all the standards you’ve been relying on so far and question everything you use while building a website. Using a standardised map tool (like Google Maps) is actually reproducing a non-choice. It also means that you don’t think about what a map means and how it shapes the understanding of a territory and a culture (the geopolitics). Developing new ways to use maps on digital tools is utterly important to de-standardise the use of maps and design new kinds of maps that are based on a specific territory and culture.

I recently did a workshop with the Low Tech Lab in Brittany to help them set up their website. We used a plug-in we recently released that shows the impact of your navigation. When we opened the website we realised that just opening the homepage required 8 megabytes, half of it were eaten up by a little Facebook timeline which was embedded into the website. It was not only absorbing half the energy, it was also taking in the data of the website. Even a simple-looking Facebook widget is both energy-hungry and a tracker that enables Facebook to follow you. Instead of relying on the available icons, it makes more sense, in terms of privacy and energy, to write down the text and add an hyperlink.

This is just an example but it shows that you need to rethink everything you’ve learnt in web design once you’re given limited energy. In addition, some of the issues we commonly have with web design (addiction, privacy, etc.) are completely fading away once you rely on limited energy. Which shows that a lot of the problematic issues we associate with big tech companies are linked to abundant energy.

I would compare a website to a house. In french we talk about “passoire thermique” (“thermal strainer.”) I want to isolate a website, a bit like you would spot and stop the leaks in order to isolate a house. Most websites are passoires thermiques. We released a report on online video recently with a think-tank called The Shift Project.

Many people are contacting me, they sound very concerned about the issue. The most recent company that got in touch was a national French television channel. Their design team is looking for new ways to reduce the impact of their streaming services. They realise that their business model is not good and want to do something for the climate, at the scale of their company. I’m going to advise them to do a workshop with their developers and we’ll go through the process of trying to design a website with an energy budget.

Why put yet another technological layer on top of the others when designing a website? Why not use energy as your guiding constraint instead? With creativity and innovation, especially visual innovation, we can find way to present what is usually represented through standards. Simply embedding a Google Map on your website doesn’t require any creativity nor any reflection on what exactly is a map.

But it seems to me then what you want to achieve is actually going in the exact opposite direction of the path that the tech and communication industry wants to follow. What you’re telling me is not compatible with 5G, the internet of things, Netflix, etc.

People seem to be living in a techno-fantasy dream. Mostly because they don’t understand the infrastructure on which it is relying. Eventually, the physical world with its energy limits and planetary boundaries will catch up with these dreams. I’ve been dedicating a lot of time in conferences and workshops explaining to people why autonomous cars will not be possible. Once you open the black box and reveal the infrastructure, people understand what is behind their dreams. You can break the spell, even in the French start-up scene.

A city I will advise this year is also trying to reduce the ecological repercussions of its digital strategy for the next 5 years. Their first concern is to set up sober digital tools that would help lower the environmental impact of the digital industry. Other cities are starting to get interested in these issues too. So i would say that the consciousness of the price that the environment is paying is growing in France.

The Shift Project, Carbonalyser, the browser extension (add-on) that makes visible the invisible climate impact of web browsing

Does a low tech life necessarily imply a return to the past, a downgrade of our ways of life? Is there any way we can make low tech appealing?

First, i think we need to deal with the term “Low tech” we’ve inherited. It’s not an exciting term indeed. We usually understand it as being in total opposition to High Tech but the reality is a bit more nuanced. James Auger was telling me recently that in the UK, they don’t differentiate ‘technology’ and ‘technique’. It’s important to be precise and understand what we are talking about: techniques or technology? In this sense, high tech is low technique and high technology, knowing that technology lies within techniques. On the other hand, the way low tech is thinking is high techniques, low technology.

Techniques implies know-how, learning the tools in a specific context to be able to engage with them, etc. It’s not automation and devices that hide all the machinery. Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life: A Philosophical Inquiry by Albert Borgmann is a great source of inspiration. It’s also far more readable then Heidegger. Another good book to think about techniques and technology is The Shock of the Old by David Edgerton. If we look at the history of techniques and of technology based on a sole inventor that invents something, we assume that this invention will be in the world as a whole. However, the use of a technique or technology can appear, disappear, reappear then fade away again and then reemerge in a different space. We need to think of the richness of techniques and technology. You cannot follow just one line of technological progress. That’s part of my teaching when I’m talking with people who live in this techno-dream.

When it comes to low-tech, that’s the term we’re left with so we’ll work with that. We might change it later on and find a better word. I know that there is the term wild tech. In any case the way we think of techniques through low-tech is so much more exciting but you need time, engagement and to some extent you also need to make it specific to the context, in the sense that it will work well on the specific territory where it operates compared to the technology that aims to be applied indiscriminately upon the whole world. The more precisely it responds to the needs of a territory, the more attractive this kind of technology will be.

Of course developers have been looking into efficiency and other issues for many years but it’s still very new in design. Design practices are structured to stimulate the rebound effect. Designers are still mostly economic lubricants. On the other hand, when developers look into efficiency, they don’t think about the ease of use or the rebound effect, they don’t care how people will use the technically nice tools they make.

Digital low-tech is also about materialising. Perhaps more importantly, digital technology has never been linked to a territory, it has always talked about “the global village”. We need to learn how to make a digital service territory-specific, which means that it will be linked to its own energy production, to weather and other parameters we need to consider. It’s much more exciting than just designing digital services where you only need to follow trends.

Thanks Gauthier!