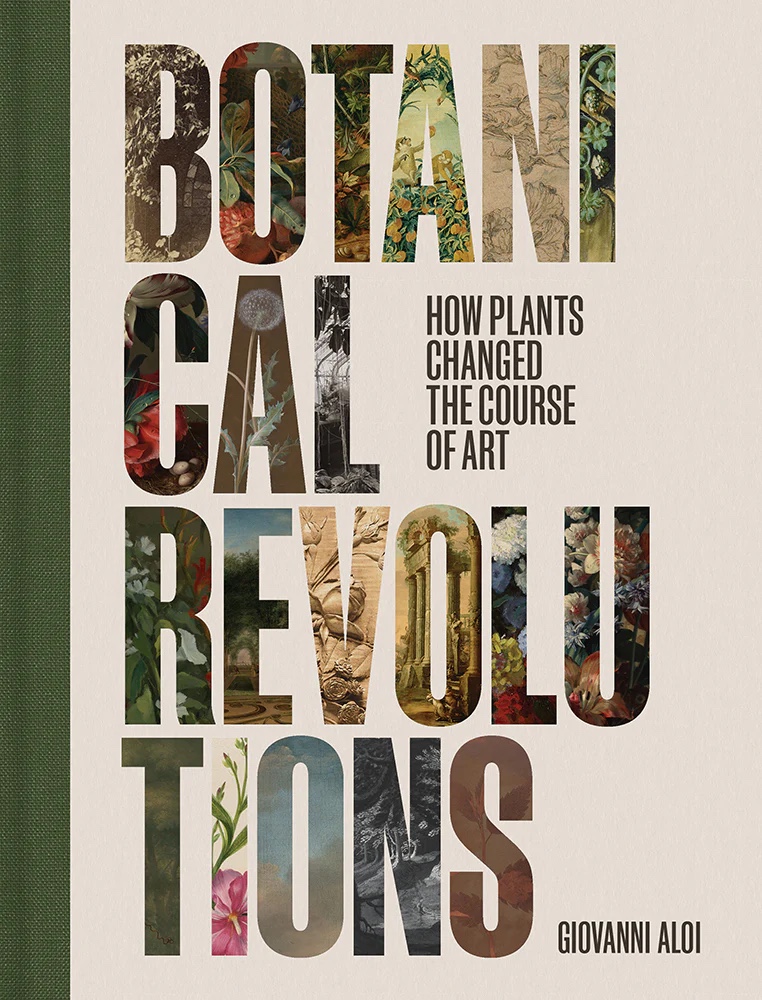

Botanical Revolutions: How Plants Changed the Course of Art, by Giovanni Aloi, an author, educator, and curator specializing in environmental subjects and the representation of nature in art. Published by Getty Publications.

Botanical Revolutions uses plants to guide us through the history of art. They are the main protagonists, the muses, the mediators, the mentors. The book takes the reader on a journey through time and space, illuminating how various cultures have used art to interact with the vegetal world.

Mona Caron, Shauquethqueat’s Eutrochium, 2021, mural

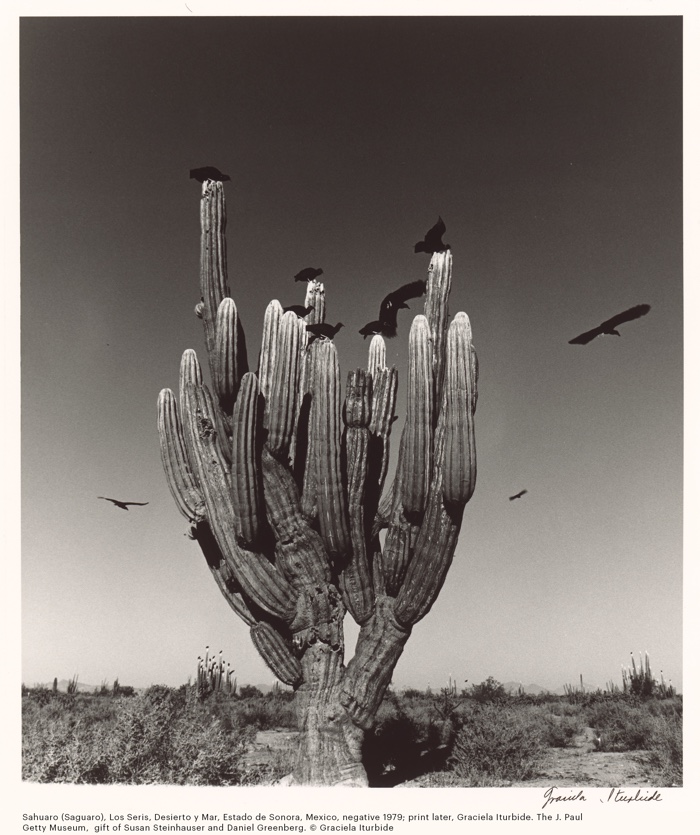

Graciela Iturbide, from the series Naturata

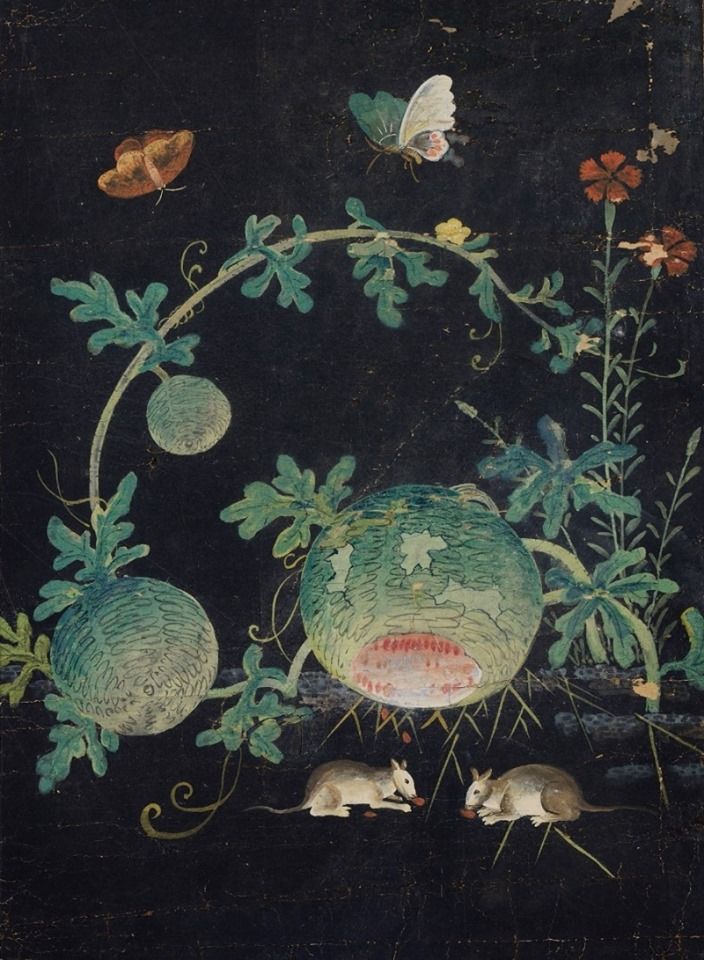

Shin Saimdang, 1504 – 1551 Korean: 申師任堂 초충도/草蟲圖 – Chochungdo (Pictures of Insects and Grass) 4, s.d. Pink Flower, Rat, Butterfly

The book gives a humbling and biting overview of Western culture’s poor understanding of the vegetal world throughout the centuries and how blind we’ve been to its intrinsic qualities, agency and ways of being in the world. Our presumed exceptional intellectual abilities have led us to believe that everything around us is passive and there for the taking. Recent years have witnessed the growth of new types of artistic, scientific and philosophical works that attempt to take their distance from anthropocentrism and recognise that the value of plants goes beyond what we can obtain, extract or produce from them.

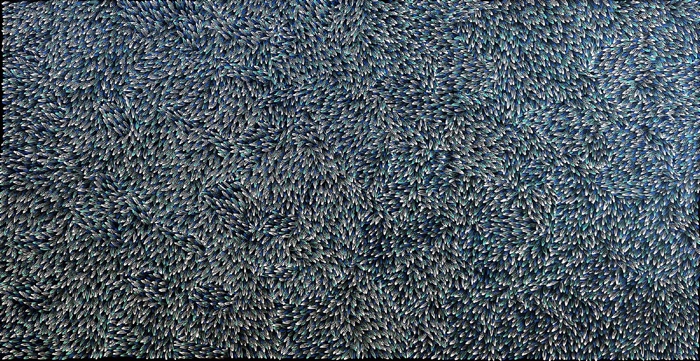

Whereas Western cultures have looked at plants as life forms that are devoid of any agency, sentience or intrinsic value, Indigenous peoples have a holistic vision of kinship between humans and other earthlings. Many of them even regard plants as custodians of identities and heritage, protectors and guardians. With every species of native plant lost, stories and traditions also vanish.

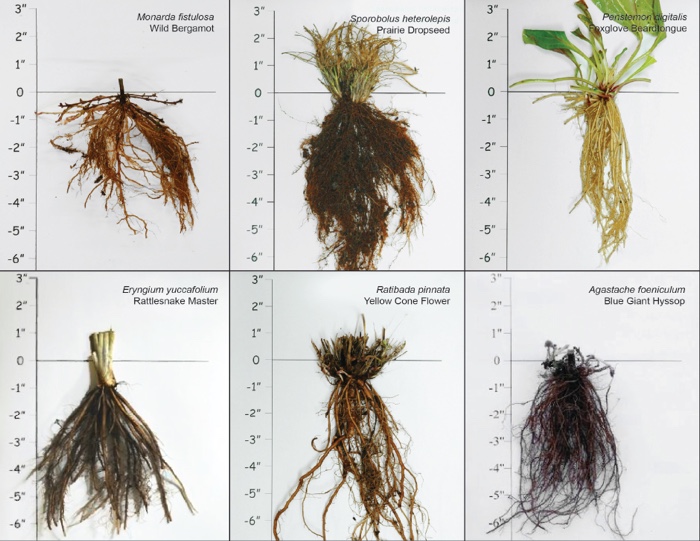

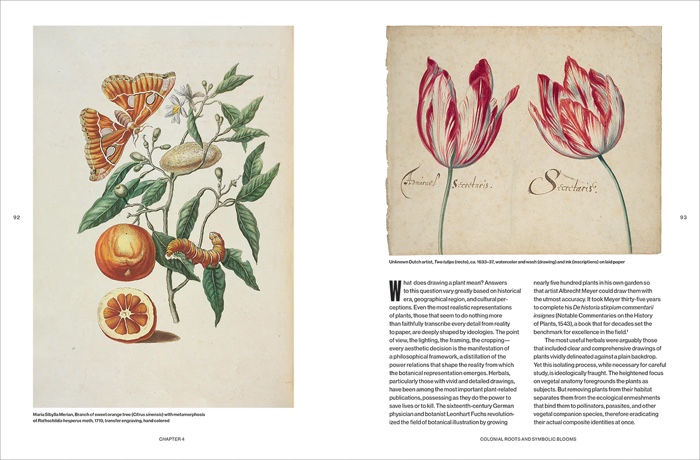

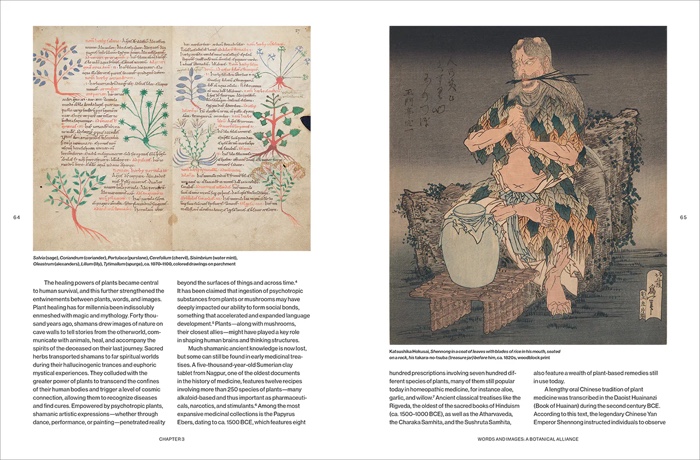

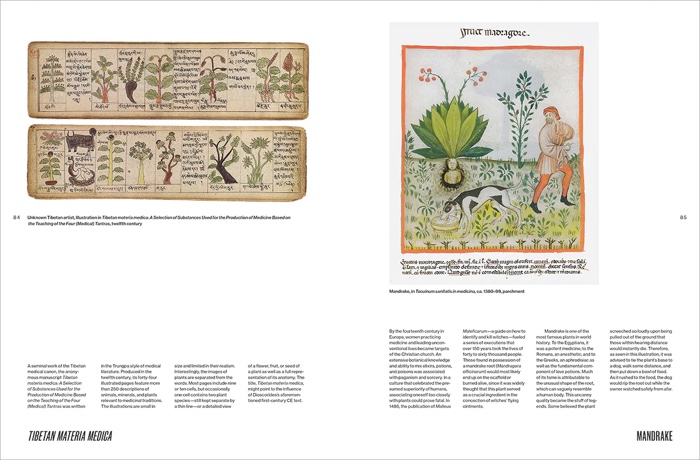

The history of plants in Western art has been marked by a pervasive neglect that reflects the power dynamics and hierarchical conceptions of colonialism and capitalism. Even the most realistic representations of plants are shaped by ideologies. The point of view, the lighting, the framing, the cropping— every aesthetic decision reveals the power dynamics that shape the reality from which the botanical representation emerges. The focus on vegetal anatomy, for example, suggests that plants are seen as subjects. Abstracting plants from their habitat separates them from the ecological enmeshments that bind them to pollinators, parasites and other vegetal or fungal companion species, therefore erasing their complex identities at once.

Jean-Baptiste Chapuy, Vue des 40 jours d’incendie des habitations de la plaine du Cap Français, ca. 1791, etching, color print

Bandolier (shoulder bag), Anishinaabe (Ojibwe), Gawababiganikak, late 19th–early 20th century

Manuela Infante, Estado Vegetal (Vegetative State), first staged in 2016

Since the early days of European colonialism, Western cultures have obsessively collected, catalogued and organised the vegetal kingdom. This thirst for knowledge stripped plants of all data deemed “nonscientific”. This approach led to the development of extremely valuable knowledge at the same time as it rejected other kinds of cultural knowledge that regarded plants as more than resources or beautiful objects.

In the East, this was far less the case. Throughout history, Asian artworks portraying plants have conveyed a sense of tranquillity, introspection and intimate connection with the vegetal kingdom, rooted in its fundamental nature.

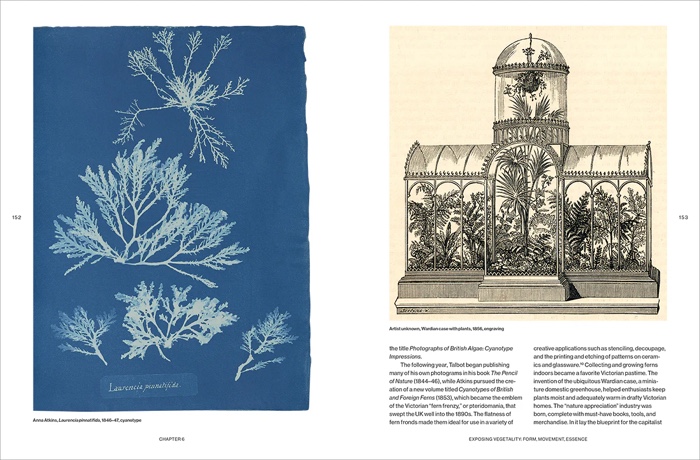

The 19th century’s emergence of a widespread appreciation of plants was often less a blessing than a curse. Western enjoyment of “nature” gave rise to an industry churning out must-have books, tools and merchandise. In it lay the blueprint for the capitalist models that today shape gardening and hobby markets. Conservatories and greenhouses, which gained in popularity among the higher classes in northern Europe, promoted trade in exotic plants. The specimens were often uprooted from colonial territories with little concern for the ecological damage caused. In that period, the appreciation of nature reached hysterical levels with pteridomania, or fern fever, and orchidelirium. Both fads were fuelled by the new illustrated publications featuring plants. The indiscriminate harvesting of ferns led to significant reductions in the wild populations of a number of the rarer species.

Unknown artist, Paradise garden mural in the Augustine convent at Malinalco, Mexico, sixteenth century. Photo: Enrique López-Tamayo Biosca

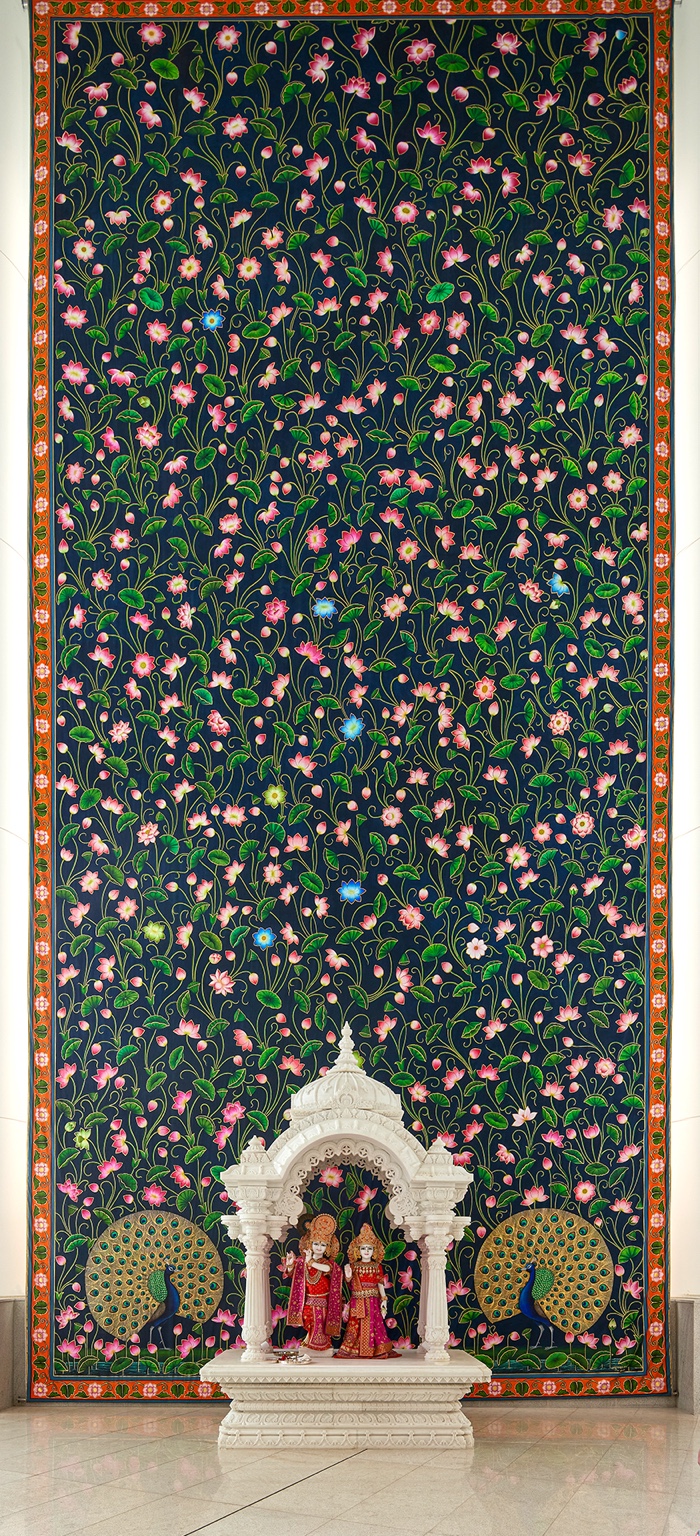

Raghunandan Sharma and Pichwai artists from Nathdwara, Kamal Kunj, 2019–20, Nathdwara pichwai painting on textile

Giovanni Aloi is a wonderful narrator who juggles geographies and historical periods with assurance. His book is packed with historical details, meditations and references to contemporary fields of research that range from philosophy to neurobiology and from queer ecologies to ethnobotany. Yet, the text flows and remains coherent. The book is informative, quietly political and very very pretty to look at.

Botanical Revolutions covers too many grounds to mention them all, but i particularly enjoyed the chapters that looked at the “adventures” of indigo. Used in the textile industry in Europe, indigo was cultivated by enslaved Africans in large-scale plantations established throughout the Caribbean, West Africa, South America and beyond. In 1791, enslaved people forced to process indigo in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) led the first and only successful slave-led revolt in history. The event led to the abolition of slavery in Haiti and its establishment as a republic independent from France. Around that time, the indigo monopoly had been broken owing to the first modern synthetic pigment: Prussian blue, which was produced by oxidation of ferrous ferrocyanide salts.

Abie Loy Kemarre, Bush Medicine Leaves, 2020

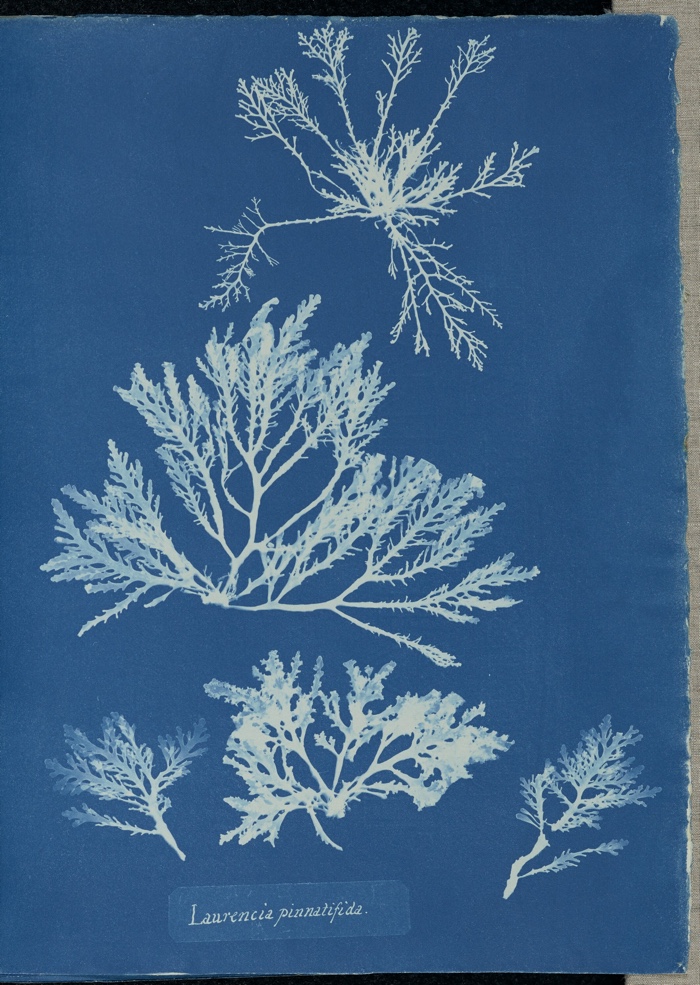

Anna Atkins, Laurencia pinnatifida, 1846–47, cyanotype

And then there are about a billion anecdotes i had never heard about. For example, i had no idea that in 1903, the Lumière brothers patented an autochrome process that used granules of potato starch dyed orange, green and blue-violet. The innovation gave images a more stable and accurate colour range.

And i knew about Tulipmania, of course. But what i ignored was that the craze is at the origins of a new publishing model: the commercial catalogue. Flowers were accurately painted against a white background, with the tulip’s and grower’s names listed together with bulb costs often indicated at the lower margin of the illustration.

One last fun fact! (At this stage, i fear that i’m only showing off my crass ignorance!) Starting in the sixteenth century, floral still lifes became extremely popular in Northern Europe owing to the Protestant Reformation’s prohibition on depictions of religious figures. Many artists started embedding divine messages in flowers, foliage and fruits.

The most important aspect of the book for me is that it explores the commodification of nature but it also details other ways of relating to plants. Alloi balances the West’s stubborn extractivism with the Islamic, Indigenous, pre-Columbian, Asian and other approaches which show an appreciation of plant life that transcended any kind of practical application. Botanic Revolutions is a book that reminds you that there are other, more respectful ways to engage with the vegetal world.

Finally, I discovered so many wonderful artworks in Botanical Revolutions. I’ll end this quick book review with some of them:

The Crow Canyon Petroglyphs, the American Southwest’s most extensive collection of Navajo rock art from the 16th through 18th centuries. Some represent corn, the most sacred plant in their creation story. According to myth, white corn emerged along with First Woman (Áłtsé asdzą́ą́ ) and yellow corn with First Man (Altsé hastiin)

Frances Whitehead, Slow Cleanup, 2008 – 2012. She enlisted the help of plants to regenerate polluted soil surrounding abandoned gas stations

Andrea Conte, Future Landscape, 2019. Installation view, Auditorium Parco della Musica. Photo: Musacchio / Ianniello / Pasqualini

Newton Harrison and Helen Mayer Harrison, Installation view of Portable Orchard, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 1972–73, mixed media

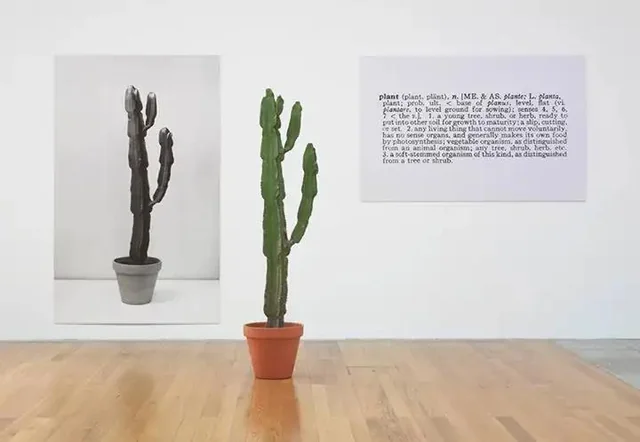

Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Plants, 1965, mixed media

Graciela Iturbide, Sahuaro [Saguaro], Los Seris, Desierto y Mar, Estado de Sonora, México, negative 1979, print later, gelatin silver print (photo)

Linda Tegg, Grasslands, 2014

F. Percy Smith, The Birth of a Flower, 1910

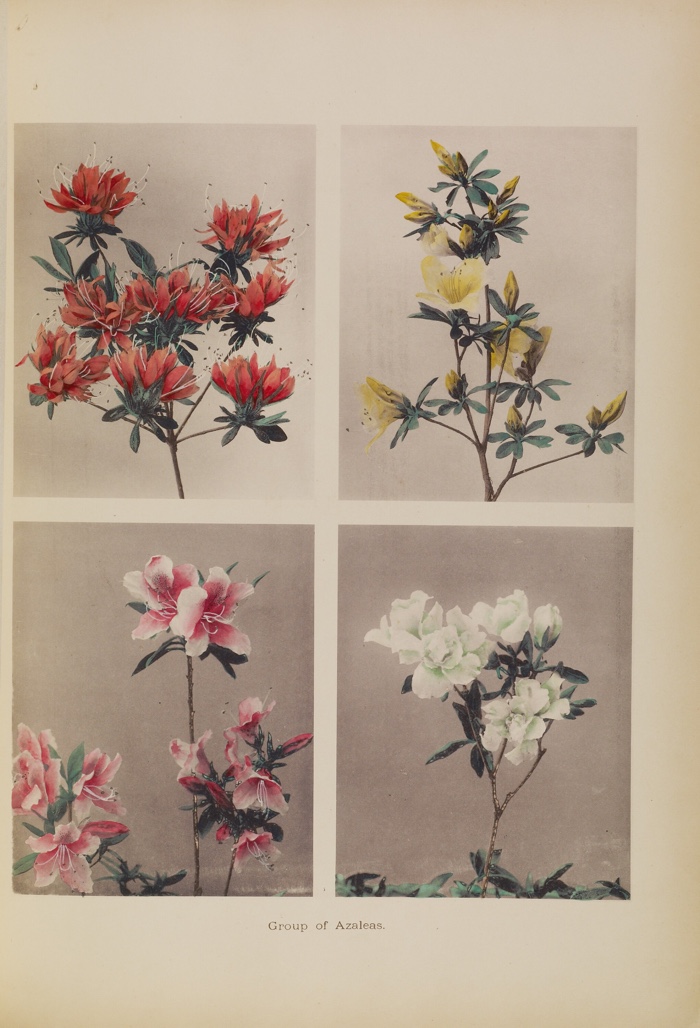

Kazumasa Ogawa, Group of Azaleas, 1896, colored collotypes

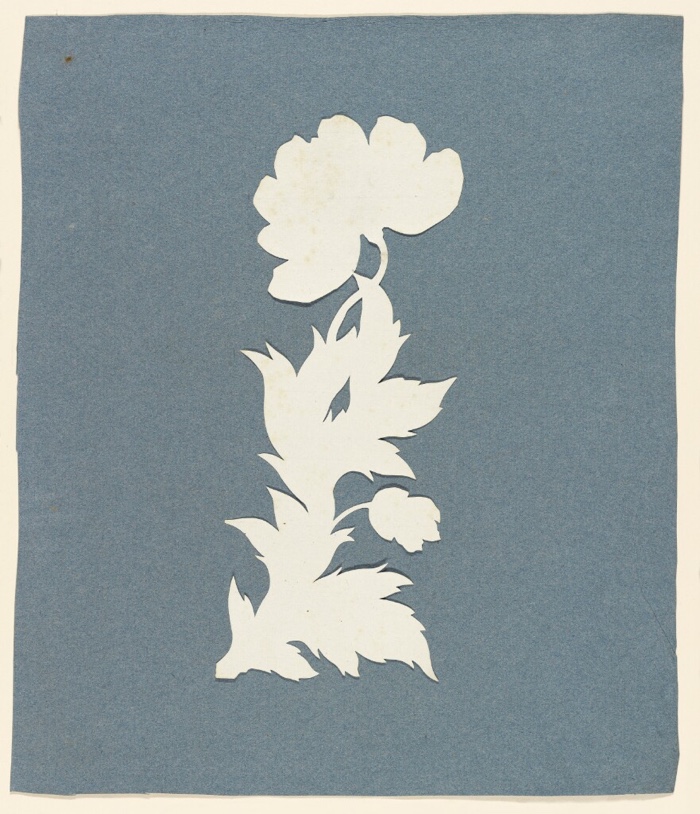

Philipp Otto Runge, Poppy, ca. 1800–1803, paper cutout affixed to paper

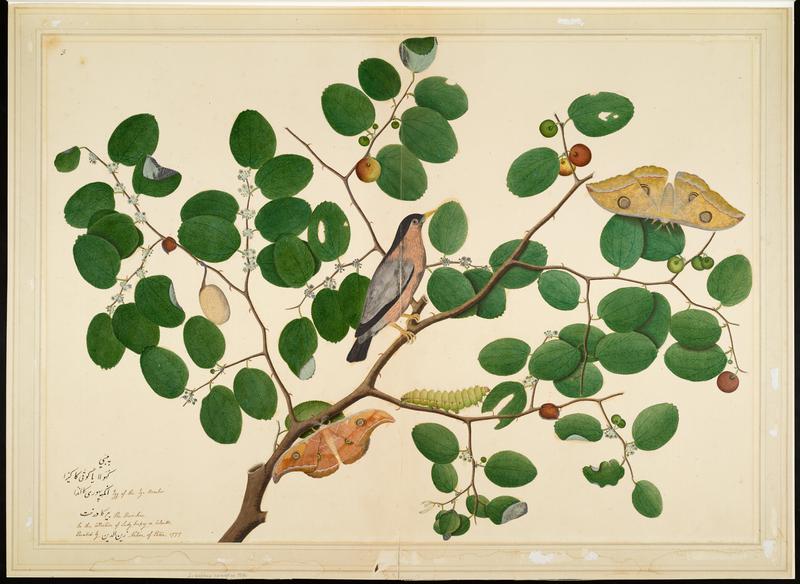

Sheikh Zain al-Din, Brahminy Starling with Two Antheraea Moths, Caterpillar and Cocoon on Indian Jujube Tree, 1777

Vishnupersaud, Potentilla fulgens, ca. 1821, drawing

The British East India Company gave rise to a new hybrid style in floral representation that combined European approaches with the detailed linearity of local Mughal art. Most Indian artists trained to produce botanical drawings for the colonisers remained anonymous, except for Vishnupersaud whose illustrations were much sought after by European collectors.

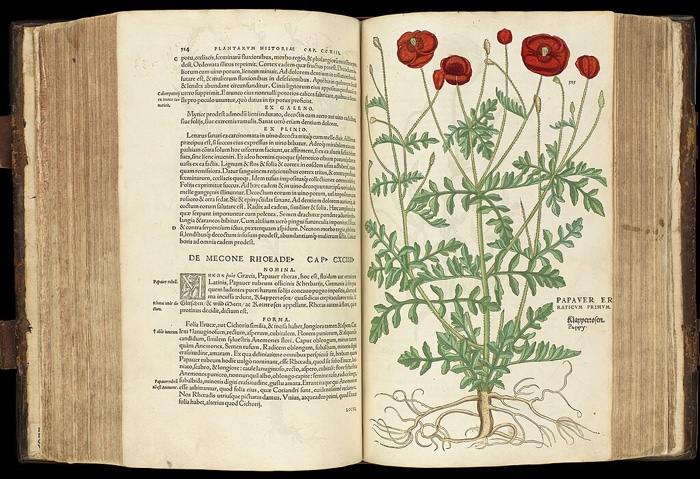

Leonhart Fuchs, De historia stirpium commentarii insignes, 1543, Papaver {poppy}

Physician and botanist Leonhart Fuchs revolutionised the field of botanical illustration by growing nearly five hundred plants in his garden so that Albrecht Meyer could draw them with the utmost accuracy. It took Meyer thirty-five years to complete his De historia stirpium commentarii insignes (Notable Commentaries on the History of Plants.)

Gherardo Cibo, Plantain, in Extracts from Dioscorides’s De materia medica, ca. 1564–84, watercolor and gouache on paper

Albrecht Dürer, The Great Piece of Turf, 1503

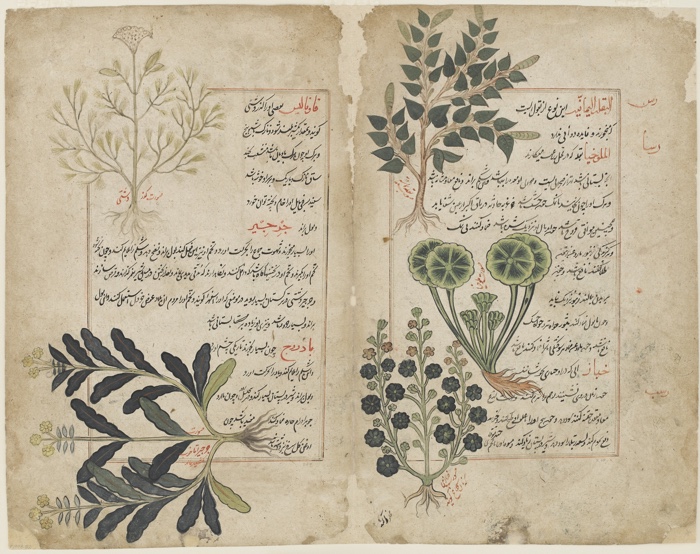

Double folio from a Kitab-i hasha’ish (The book of herbs), 1595

Unknown North Italian artist (Lombardy), Illustration in Tractatus de Herbis, ca. 1440, parchment

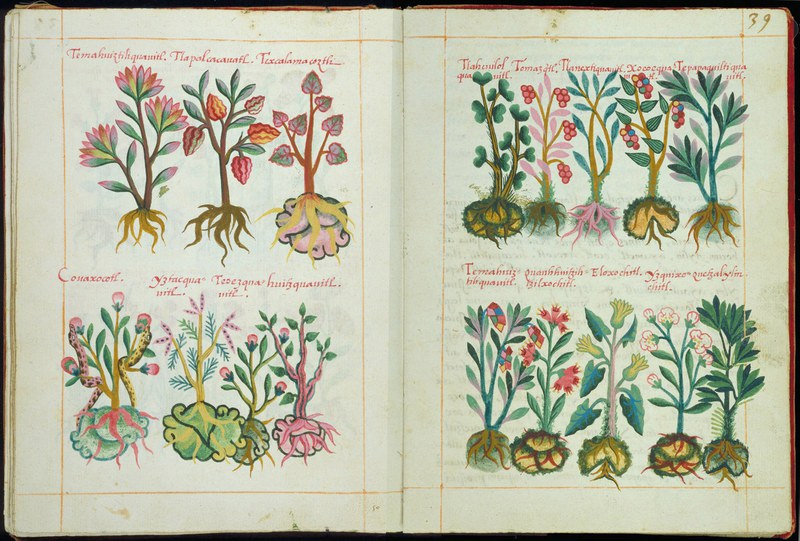

La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España (today known as the Florentine Codex), the book features more than two thousand illustrations made by twenty-two Indigenous Nahua artists working under the guidance of Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, 1540-1585

Martín de la Cruz, illustrations in the Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis, 1552, Aztec manuscript

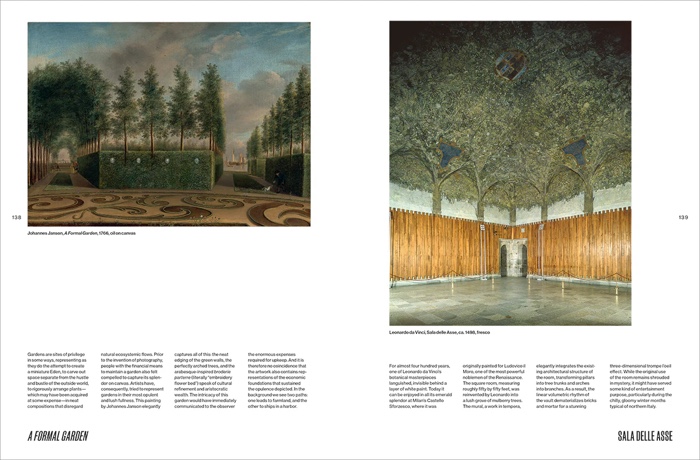

Book spreads:

Related book: Film X Autochthonous Struggles Today, Art and Creativity in an Era of Ecocide, Vegetal Entwinements in Philosophy and Art, etc.