Previous episodes of Bodily Matters: Human Biomatter in Art: Part 1. The blood session; Part 2. At the morgue and Part 3: On expendable body parts.

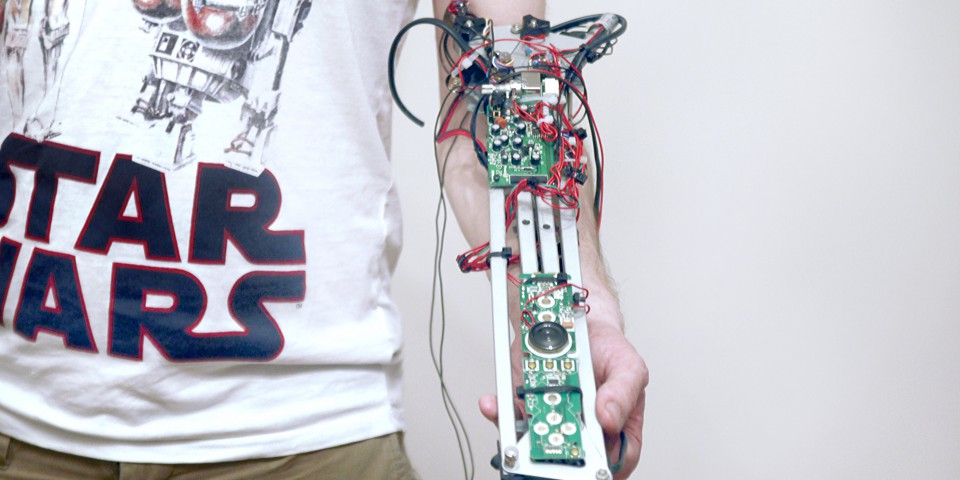

::vtol::, reading my body

Bharti Parmar, Shag (detail), 2012. Credit photo: ©Bharti Parmar

Part four (only a couple more to go) of the notes i took during Bodily Matters: Human Biomatter in Art. Materials / Aesthetics / Ethics, a symposium that took place a month ago at University College London. The impeccably curated event explored how artists use the human body not merely as the subject of their works, but also as their substance.

Session 4. Liminal Matters: Self-portraiture, Body Surface & Memory was one of the most fascinating sessions for me. Full of weirdness and wisdom. It started with a 19th century sculptor who made a life-like statue of himself complete with his own hair and teeth, proceeded with a set of artists who work with tattoo and the latest technology and ended up with artworks, socks and other artifacts made of human hair.

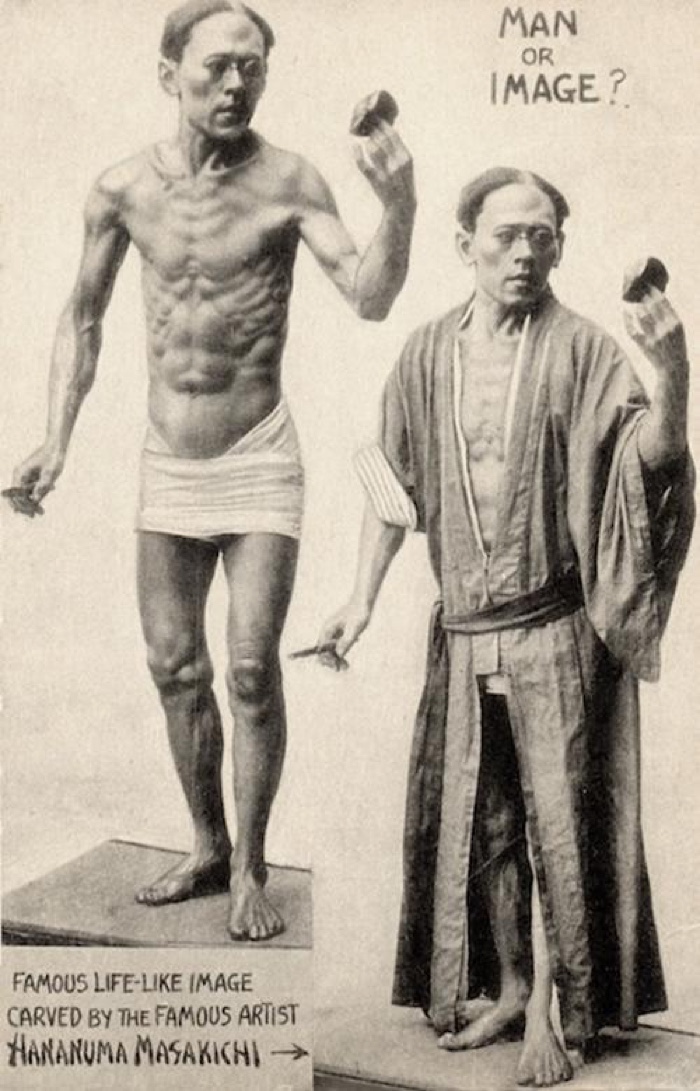

Hananuma Masakichi, the artist and his statue. Or vice versa. Photo via Oddity Central

Ana Dosen (PhD candidate (Singidunum University, Faculty of Media & Communication)’s talk Reverse Pygmalion: Hananuma Masakichi’s True ‘Ruin’ looked at a Japanese sculptor who in the late 19th century made a life size statue of himself. Learning he had tuberculosis, Hananuma Masakichi decided he had to make an hyper realistic self-portrait that his girlfriend could love after his death. The statue was made of over 2000 pieces of wood seamlessly assembled using wooden pegs, joints and glue. It was lacquered and painted the same colour as the artist’s own flesh and to make it even more life-like, Masakichi is said to have pulled his own hair, fingernails, toenails and teeth and incorporated them into the artwork. He actually posed next to the sculpture and had people guess which one was the original and which one was the replica.

He died 10 years later, aged 63.

Dosen wanted to analyse the statue in the context of Jacques Derrida’s belief that any self-portrait is always a departure from the original. The artist is either looking at himself or at his canvas and can thus only draw or paint from memory. If an image is always a departure from the referent, especially apparent in self-portrait’s impossibility of emanating the experience of self observing, how selected biological materials of the artist, integrated in the work of art, contribute to “reality” of phantasm? Does human biomatter decrease the temporal distances of ruin in self-portraiture?

Professor Hiroshi Ishiguro of Osaka University in Japan and his own robot double. Image via Wired

Interestingly, someone in the audience drew parallels between Hananuma and Professor Hiroshi Ishiguro who made a robot copy of himself and who undergoes plastic surgery so that he can keep on looking like his robot.

In Killing the Zombie: The Transformation of Contemporary Abstraction through the Translation of the Tattooed Body, Karly Etz, PhD candidate (Penn State University, Art History Department) explored the work of three artists (Alison Bennett, Dmitry Morozov, and Amanda Wachob) who use technology to explore skin as a surface to create art, revive abstract art and challenge the usual dynamics of the art market.

Through their art objects, these artists recognize the importance of the human body as a site of socio-cultural critique and resistance, and utilize that space as a springboard for their commentary, not only on the status of the contemporary art object but also on the place of the human body in an ever-expanding, technological world.

Etz pointed that these artists’ works are highly innovative, they are not the first to use skin as a site of social commentary:

Santiago Sierra, 160 cm Line Tattooed on 4 People El Gallo Arte Contemporáneo, Salamanca, Spain, 2000. Photo Tate

In 2000, Santiago Sierra paid four heroin addict prostitutes the price of a shot of heroin to give their consent to have their back tattooed with a line. The performance not only illuminates the desperation of these women, it also shows the ability of tattoo to highlight the power dynamics at the heart of capitalism.

Mary Coble, Blood Script, 2008

In 2008, Mary Coble had a tattooist write down on her skin (but without ink) all the hate speech she had been exposed to. The beautiful calligraphy shows the pain inflicted by the hurtful words but it also enables the artist to take ownership of the insults.

Now the artworks at the core of Etz’s talk are Shifting Skin, Reading My Body and Skin Data.

Alison Bennett, Shifting Skin, Deakin University Art Gallery, 2013

Shifting Skin explores the blurring boundaries between material and virtual via the skin. Images of human tattooed skin were captured by moving a flatbed scanner directly over the body. When gallery visitors view the work through an app on a mobile screen, the body that had been flattened gets its third dimension back.

The experience merges the virtual and the physical, the embodied and the digital. The viewer must be physically in front of the print and move before it in order to trace the contours of the 3D virtual object.

::vtol::, reading my body

::vtol::, reading my body

::vtol::, reading my body

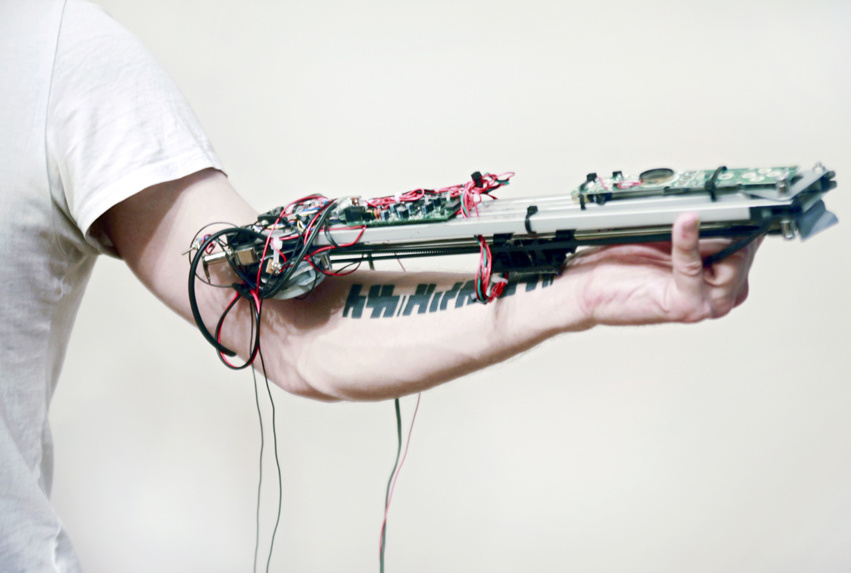

In his work Reading My Body, artist Dmitry Morozov turned his tattooed arm into a sound controller. The tattoo can be replicated on other bodies but it is incomplete without the accompanying machine. What makes the work interesting is that the artist has created a new kind of abstract work that will evolve as he ages, as his skin wrinkles and thus produces a kind of soundtrack for his own body disintegration and for the gradual obsolescence of the technology he is using.

This artefact combines human body and robotic system into a single entity producing an adaptive system that benefits mutually from each other producing a new creative hybrid.

Amanda Wachob, Skin Data. Photo via Motherboard

Amanda Wachob, Skin Data. Photo via Motherboard

Above: the mapped data from each of Wachob’s tattoo designs. Below: the tattoo design. Image: New Museum, via Motherboard

Amanda Wachob, Skin Data. Photo via The Wild Magazine

Tattoo artist Amanda Wachob collaborated with neuroscientist Maxwell Bertolero to collect and analyze data produced by her tattoo equipment while she is tattooing a subject. The machine (which is otherwise employed in medical context to record brain activity) recorded the time and voltage spent to ink each participant to the project. The information was then translated into colourful motifs.

The three works create an intimate connection between technology and the body, they also provide abstract art with a social dimension that was missing in the last decades.

Bharti Parmar, Shag, 2012. Credit photo: ©Bharti Parmar

Chiengora socks. Photo via Ecouterre

Ploca-cosmos; hair, entanglement and the universe, the talk by artist & independent scholar Dr. Bharti Parmar investigated artworks and research projects in which human hair features as a central trope.

The title of the talk stems from a book written in 1792 by London hairdresser James Stewart. A neologism combining plocos (hair in greek) and cosmos (universe), ‘plocacosmos’ encapsulates how worlds are reflected in metaphors about hair: bigwig, hair’s breadth, barnet fair, high brow/low brow, etc.

In Victorian times, wearing or crafting jewellery made of or with the hair of a loved one wasn’t anything strange. But nowadays, the idea of using human hair as a fashion, art or design material repels us. Not only because of its association with the horrors of the Holocaust but also because our relationship to ‘dead’ body parts has changed over time. However, Parmar spent 9 months hand-knotting a large shagpile carpet made of human hair using traditional wigmaking techniques. The work is deeply upsetting because of the way it attracts and repels equally.