ATMs fingerprint-based biometric technology in Malawi. Photo via African Business

Back in April, i was in Berlin for the Anthropocene Curriculum and very much looking forward to Truth Measures, an evening of talks and performances at Haus der Kulturen der Welt which examined the techniques and technologies for gathering data, truth, evidence and how they produce what is true and what isn’t. Unfortunately, right before that i had attended a fantastically informative workshop that involved walking for hours under the pouring rain and i had to chose between either going back to the studio i was renting and getting dry or getting the flu or whatever people get sick of when their brand new creepers make squishy squishy sounds with their every step. I thus missed the evening and the morning after everyone was telling me about this talk i would have loved.

It was called Biometric Capitalism: Infrastructures of Identification and Credit Risk on the African Continent in the 21st Century. I ended up meeting its author, Keith Breckenridge, a couple of days later. We were supposed to have a conversation but i ended up pestering him with questions about his work. Breckenridge is a historian, a Professor and Deputy Director at WITS Institute for Social and Economic Research in Johannesburg. My invasive cross-examination of him was one of the most exciting moments of my week in Berlin. HKW has recently uploaded on youtube the video of the presentation i had missed. Whoopee! Whoopee!

Biometric Capitalism: Infrastructures of Identification and Credit Risk on the African Continent in the 21st Century. Presentation by Keith Breckenridge

In this short presentation, Breckenridge explores what biometrics means in African countries, how it is used and by who, how it is affecting the poorest people in the world, how it fails, etc. And most importantly why we should be concerned about it.

Here’s the abstract:

A new and distinctive variety of capitalism is currently taking form on the African continent. States are being remade under the pressures of rapid demographic growth, intractable conflicts over boundaries, domestic and international security demands, and the offerings of multi-lateral donors and international data-processing corporations. Much of this turns to enhanced forms of state surveillance that is common to societies across the globe, but the economic and institutional forms on the African continent are unusual. Automated biometric identification systems present former colonial states with apparently simple and cost-effective alternatives to the difficult and expensive projects of civil registration. In many African countries, commercial banks are offering to bear the costs of building centralized biometric population registers, explicitly having in mind the development of a national identification database and commercial credit risk scoring apparatus, a combination that aims to transform all citizens into appropriate subjects for automated debt appraisal.

And here’s a few notes i wrote down while watching this video. I’m only adding them here in case anyone in this audience absolutely hates watching video….

For most of the last century, vastly more people in Africa have been involved in agriculture than in trade. The form of capitalism and the institutions that capitalism depended upon have been dependent on mining and on mineral extractions and in particular in the last 10 years on oil. That’s what dominated investments, state revenues, company revenues, individuals incomes especially property forms, etc.

George Osodi, from the series Oil Rich Niger Delta, 2003-2007

It is well established now that there are many different kinds of capitalism. So what is biometric capitalism?

Biometric Capitalism is a system of economy activity organised around the centralised unity database of biometrically ordered populations registration where the identification is done on the basis of people’s fingerprints or some other iris that can allow for unique identification (or close to unique identification.) It is justified morally and politically by the politics and the technologies of cash transfers.

In South Africa, 40% of the population receives a monthly cash transfer payment from the state through a biometric system. There are many attempts of similar basic income grants on the African continent for people who are locked out of formal work. Banks are often the ones who are funding the development of these population registers and they are developing shared infrastructures for credit surveillance that are derived from the original FICO scores.

The FICO algorithm has spread very widely around the world and it has been adopted very enthusiastically in the last 5 years. Non-governments and governments are pushing the development of tracking systems around cash transfer schemes and student loans. Last year, the big complaint of students in South Africa was that the debt that they have to cover their subsistence while studying at university is handed over to the banks. If they don’t service the loans they are blackmarked very quickly. That is the first thing an employer will query when a graduate goes and applies for work. If you haven’t been servicing your debts, you don’t get shortlisted for an interview. You thus lose your ability to pay back the loan. Those loan schemes exist in almost all countries on the continent. These systems are heavily influenced by infrastructures of biometrics, government and banking that were first developed in South Africa over the course of the last century. It’s important to understand that biometric capitalism confronts two fundamental problems about the nature of the state and the economy on the African continent:

The first problem is that unlike the conventional barbarian and Foucauldian understanding of power knowledge, states on the African continent have limited knowledge about their population. Most births and most deaths are still not recorded. Even South Africa has only started recording the majority of births in 2002.

Unlike India, African colonial states did not count their population. They had no interest really in anyone, except the white people who lived in the cities.

Hundred years ago already, the colonial officials said “Don’t listen to Africans, they lie about who they are. The only way you can know for sure is if you record their fingerprints.” And much the same juxtaposition exists today.

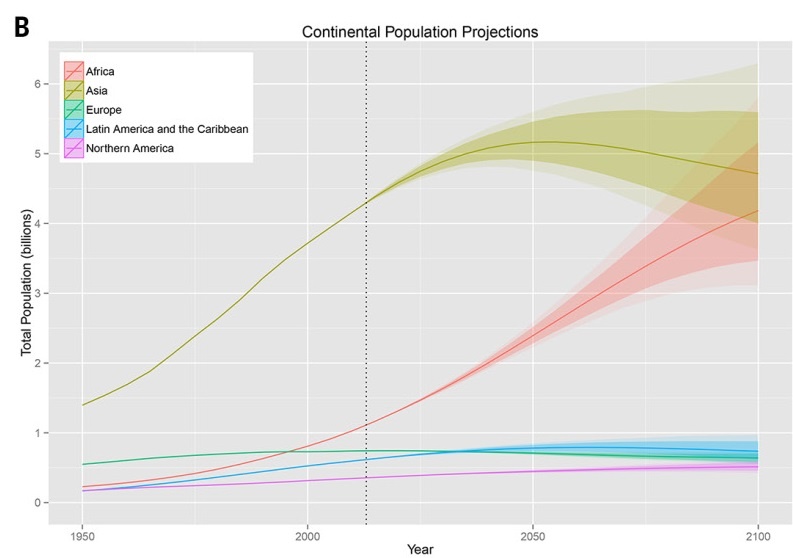

Projections of human populations to 2100, per continent

The second problem is demography. Most African states have experienced dramatic increases in population over the last generation, going from comparatively low densities to some the highest ever recorded. The current estimate is that in 20150 it will be between 2 and 2.5 billion and that by the end of the century there will be between 4 and 6 billion people on the continent.

Most states are scrambling to build bureaucratic mechanisms to get a grip on it. In each case we can see a convergence towards an administrative architecture that emerged first in South Africa. It’s radically centralised biometric identity registration, with privatised biometric cash transfers, universal credit histories, credit histories that come to serve as instruments of moralisation. So if nothing else really works, we can at least identify what kind of person you are by looking at your credit history.

I could have illustrated the ID project in India with a more relevant image but i just love that this dog in Madhya Pradesh got an Aadhaar card for itself

There are other examples throughout the world, the most important is UID project in India.

Two things stand out:

1. It’s not a card, it’s a number. The government only gives you a number. It’s intangible. People have demanded a card, some have laminated the paper receipts.

2. A billion people have been registered in the last 5 years which makes it by far the most successful registration project ever attempted.

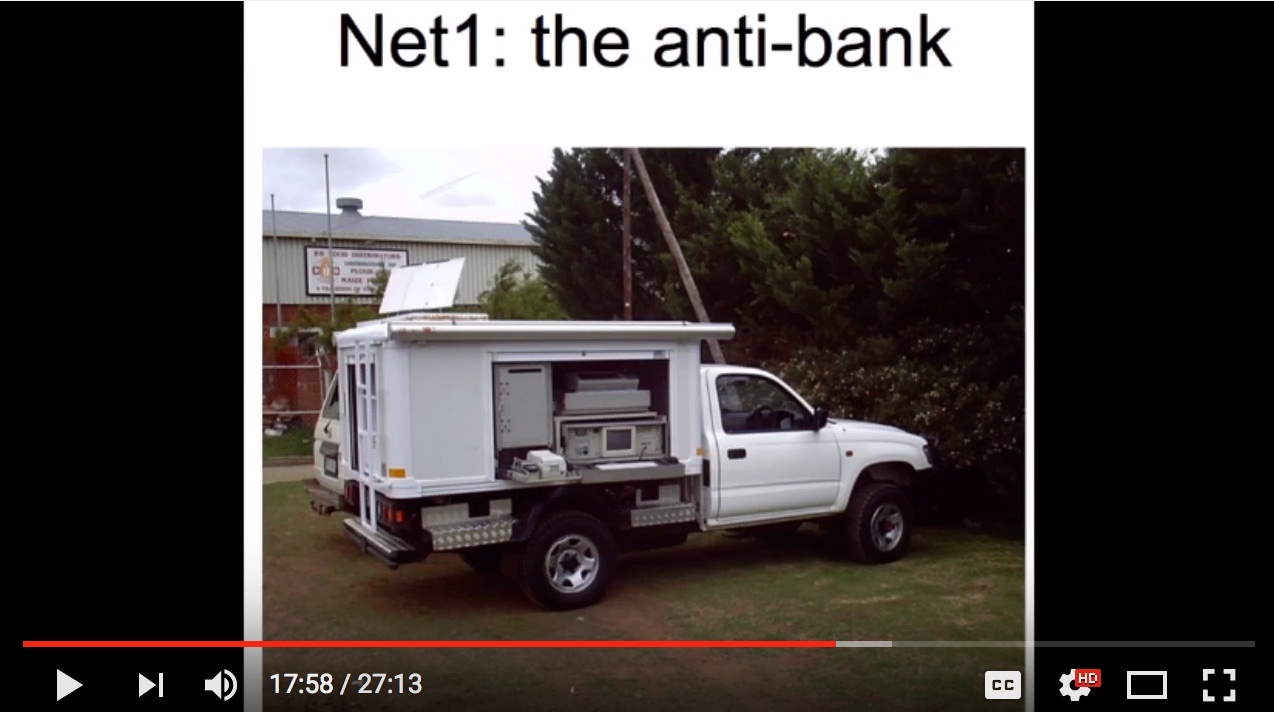

Screenshot from Breckenridge presentation

Pictures of how this works in South Africa:

The first large-scale application of fingerprint-based digital biometrics was in the delivery of pension benefits in the former KwaZulu homeland in the late 1980s. Incidentally, this was the first trial of sound recognition and officials say they couldn’t get the people to be calm enough about it. They were initially reluctant to use fingerprint, thinking that people would associate it with the Apartheid state. But in the end they used fingerprint simply because that was a technique that everybody understood, the subjects and the officials.

The kits used in the 1990s were the same standardised equipment you can find today. It’s essentially ATM machines that are hooked up to a little biometric device.

Screenshot from Breckenridge presentation

Net1 UEPS, ‘the anti-bank’, is a private company that is now the direct agent of the South African model of biometric government. It has contracts for government grants and pensions in Namibia, Botswana, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Ghana, etc. This company is explicitly targeting offline, illiterate bank customers, what are called ‘unbanked populations’. The company has been subject to many legal disputes, but there’s no mistaking its momentum in Southern Africa and around the world. There are 22 million people inside the Net1 database itself. This is a separate system, it’s not the same one used by the government. Their business model involves providing a banking infrastructure so they are lending to the people who are paid grants by the government and of course they have access to all the income these people earn so they can lend to them without any risk at all. Last week, the World Bank bought 10% of the company for a hundred million dollars.

These biometric systems in South Africa are connected very closely to credit surveillance which didn’t really exist in the country in 1990. Between 1990 and 2016, we’ve seen the extension of the American system of automated information about your credit: not only what you borrow but also what you pay off on your utility bills as a means of gathering information about your suitability as a bank customer. The credit reference bureau collects your name, your identity number, your address, who your employer is, your debts and payments on your telephone account, your cable tv, cell phone contract, your utility bills, your credit cards and mortgages. This is a model used everywhere now. The distinction is that in South Africa, the state uses it as a moralising instrument. If i am an employee of a local municipality, i will decide whether you are a virtuous tenant by looking at your credit history. There are something like 20 million individual profiles in the system in South Africa and 50% of them are what we would call blacklisted customers. They can’t get access to credit, they can’t typically get access to any of the things that they are asking for, whether it’s access to a rent or the opportunity for employment.

Over the last 5 years, this system has started to move rapidly around the continent.

The fantasy of capturing the unbanked lays behind the first system of biometric cash or biometric money ever implemented on the planet. In 2007, Net1 was contracted by the central bank of Ghana for a national banking switch (the E-Zwich) that requires all bank transactions to be biometrically authenticated (in theory because it didn’t work like that in practice.) So you put your fingerprint on the reader, somebody else has to do the same in order to move money from one account to another. The scheme has been a dismal failure: the machines don’t work very well, they don’t access the cellular network and generally people have been very reluctant to use it. Ghanians haven’t taken very kindly to the idea that they should be submitted to a different technology to the one that they would use when they are in London. So there has been resistance from the rich and as for the poor, they don’t have any money.

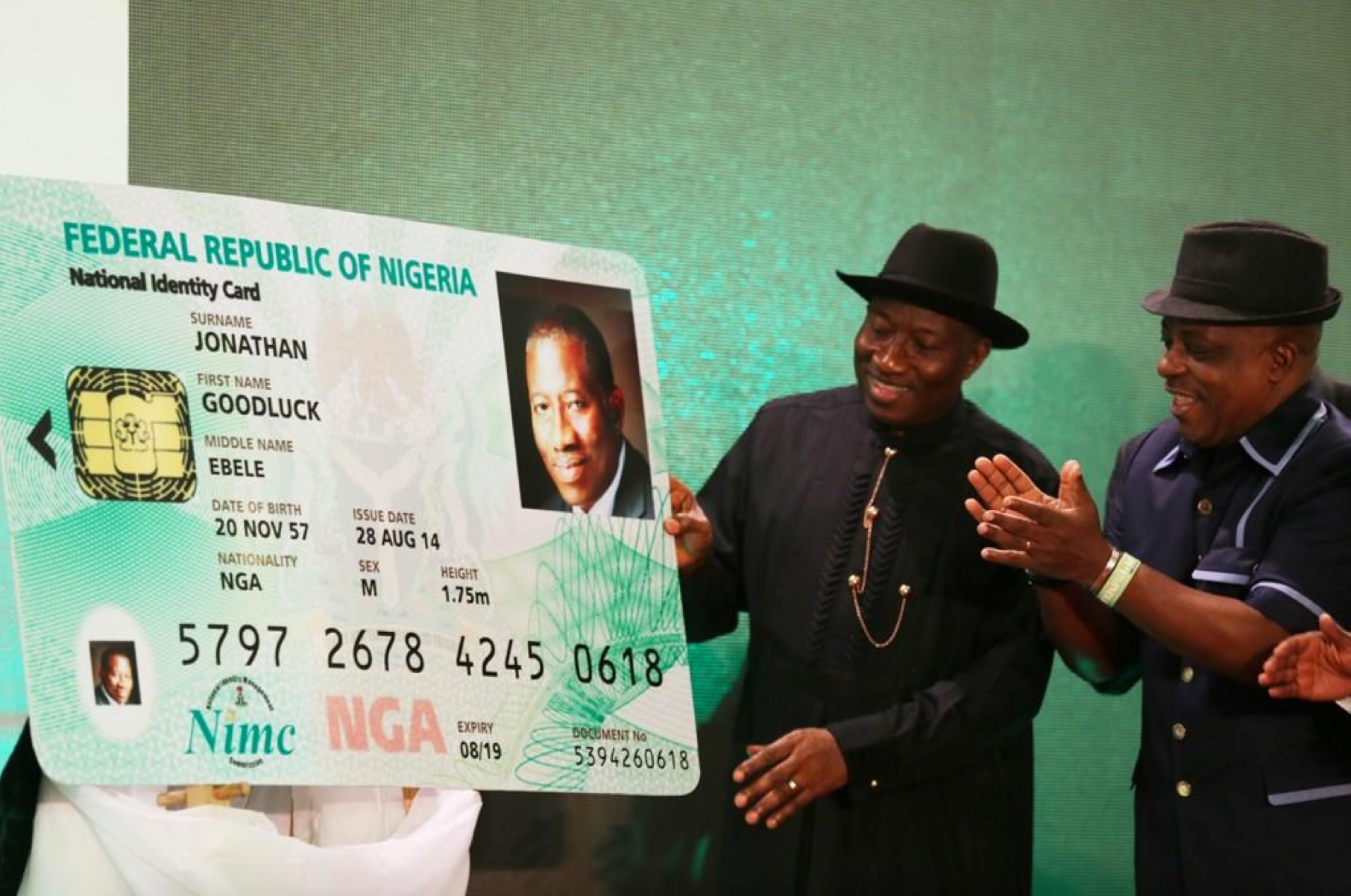

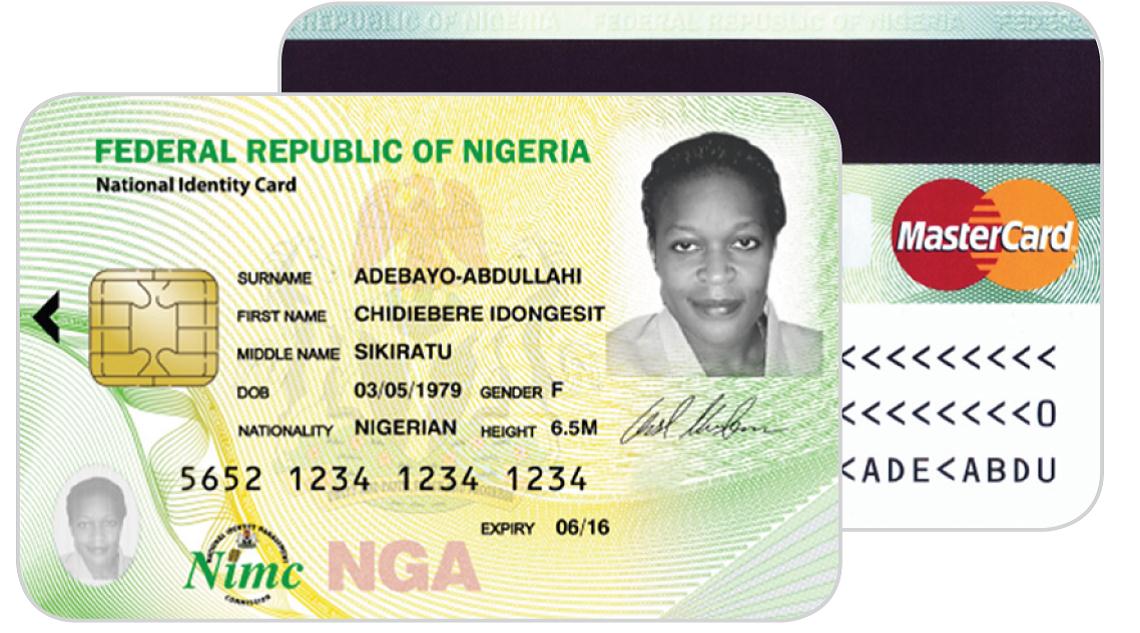

Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan looks at the replica of his electronic identity card during the launching of the cards in Abuja

MasterCard-branded National Identity Smart Cards with electronic payment capability

The most outrageous of these schemes was the announcement in 2013 that MasterCard would be issuing the Federal Republic of Nigeria identity card. It sets in place an astonishing precedent and there is very little legal apparatus to deal with it.

Of course many of these things don’t work as flawlessly as scheduled.

A group of youths display their disfigured fingerprints at Maili Saba quarry in Bahati, Nakuru. More than 40 youths working at the quarry have no Identification Cards. Photo: Kipsang Joseph/Standard

People working manually, like bricklayers, often present damaged fingerprints and they are never going to be biometrically captured. There isn’t currently a way to deal with this

Then there’s the problem of efficiency: after a decade of issuing identity cards, Nigeria have only issued them to 10 million people. There are 180 million Nigerians…

The model, however, remains in place. There’s no sign in other word of official hesitation or of remorse.

Breckenridge then read this article about the biometric registration of Kenyans. The process will involve scanning of existing identification documents, facial scans and taking of finger prints. Children under 12 years will have their irises scanned. The register will also capture land details, assets and registered companies, with a view of enlisting those within the tax bracket who are not paying duty.

So what is Biometric Capitalism and where is it happening?

Banks and states are now in an intimate embrace, funding each others’ work. Global corporations, donors, kit manufacturers all act together in a network.

Laura Mann has recently finished her PhD on this topic, focusing on Kenya. She describes an industrial policy that favours the creation, accumulation and sharing of data (currently without meaningful privacy limits); hinged on the creation of biometric national population registers that are hooked into the credit history system.

This apparatus is antagonistic to the strategies of subsistence and accumulation that have dominated on the continent to this date: resource extraction.

There are some sinister and in fact distressing new forms of coercively imposed civic virtue that will require people to act as individualised entities and be preoccupied with their algorithmically generated reputation.

Personal debts, debt service and the risks around the servicing of those debts are becoming the dominant forms of property and profit on the continent. In an economic landscape where mineral titles have long predominated. This is capitalism in a world with very weak states, where growth is demographic and where personal debt is the most valuable resource.

Videos from the same evening:

Truth Measures | Technosphere Truth?,

Truth Measures | The Common Sense,

Truth Measures | Contra Diction: Speech Against Itself.

Related stories: Confessions of a Data Broker and other tales of a quantified society, MSA: The Microbiome Security Agency, Obfuscation. A User’s Guide for Privacy and Protest, etc.