The Oaxaca Valley in Mexico is regarded as the heartland of corn diversity. Not only can cultivation of the plant in the region be traced back to over 6000 years ago, it also presents the highest genetic diversity of corn in the country.

Yet, this rich and ancestral biodiversity is threatened by the introduction of genetically modified seeds in the region. In November, 2001, David Quist and Ignacio Chapela from the University of California, Berkeley published an article in the journal Nature in which they reported that some of Oaxaca native corn had been contaminated by pollen from genetically modified corn. Unsurprisingly, the essay was heavily criticized by academics who had suspicious ties with the biotechnology industry.

BIOS Ex machinA: Serán ceniza, mas tendrá sentido ligeramente tóxico

BIOS Ex machinA: Serán ceniza, mas tendrá sentido ligeramente tóxico

Marcela Armas and Arcángel Constantini, Milpa polímera

Marcela Armas and Arcángel Constantini, Milpa polímera

An exhibition at the MACO, Oaxaca Contemporary Art Museum, reflects local attempts to preserve Oaxaca’s rich genetic heritage. The ‘corn issue’ cannot be reduced to a fight against the transgenic industry, it is also a battle to preserve a whole culture, an identity and a certain vision of the world.

Bioartefactos. Desgranar lentamente un maíz (Bioartefacts. Slowly treshing corn) presents 9 installations which highlight the ‘artefact’ nature of corn. The plant is a biological artefact because it is the result of a human domestication that took place thousands of years ago and it has in turn shaped the whole country over as many years.

The works exhibited include a robot that 3d prints then plants seeds made of a biopolymer created from corn (PLA), an installation that monitors and visualizes the breathing of corn as well as a series of corn plants connected with electrodes to record the interaction between plants and humans.

Macedonio Alcalá street in Oaxaca. Photo courtesy of Arte+Ciencia

Macedonio Alcalá street in Oaxaca. Photo courtesy of Arte+Ciencia

I haven’t visited the show but the theme, the works selected and the political undertones deserved to be further investigated so i contacted María Antonia González Valerio, curator of the exhibition and director of Arte+Ciencia (Art+Science), asked her for an interview and she kindly agreed to answer my questions.

Hi María! Could you explain the political and economical context of the exhibition?

The exhibition faces a difficult political and economical context in Mexico. Political decisions, in general, are being taken without including the actual living conditions and opinions of Mexican people. This makes us ask how is a community organized, how is it build. Which, of course, has no easy answer. It depends not only on the cultural context of the community, but also on the economical context. Diversity of possibilities of organization is something that we want to stress with the exhibition. Given the political context, that is very artificial and faraway from everyday life, and given the economical conditions, that in general terms and related to politics are benefiting the big and international enterprises, we need to find a way to preserve cultural diversity and biodiversity. This is not an easy task. But if we can show that there are many ways to dwell in this world, and that the capitalism-Western style is still not the only one, but a possibility among others, then we are making a strong point. It is then very important to highlight the complexity of the problems, the many perspectives, the way in which they are related and co-dependent, that is, that economical and political context have a lot to do with cultural diversity and biodiversity.

BIOS Ex machinA: Desde adentro

BIOS Ex machinA: Desde adentro

Why does the exhibition focuses on corn, rather than any other cereal or edible plant?

Corn is a special plant for Mexico. It has many layers for us. Corn is related to cultural identity, land, food, religion, mythology, rites, family, economy, animals, etc. By stressing the ways in which corn is produced, grown and used in different contexts, we want to meditate on the different aspects that constitute also different worldviews.

Corn is still the basis of Mexican nourishment. What is the relationship that we have to our food? We can at least point to the industrialized way in which it is being produced in the north of the country, the traditional way like in rural Oaxaca, and the indigenous way also taken Oaxaca as an example. From the very much-mediated relationship to food that we have in the cities where everything comes from markets and supermarkets, to the self-subsistent system of corn growth and consumption in rural Oaxaca, we can think about the different ways in which we build our world. Instead of thinking of opposites, I believe that people from the cities have a lot to learn from the countryside, not only in respect to food consumption, but also from the different ways of life. In the same sense, the city has a lot to teach to the countryside.

We cannot face the problem of corn, food, GMO’s, biotechnology, etc. only thinking about economical, biological or scientific issues, the cultural aspect is very important. When we talk about different ways of producing corn, from rural to industrialized, we are not talking only about machines or monocultures, but really about cultural diversity.

Art is one of the better ways to show this cultural diversity that at the same time is intimately related to the natural world, which for us now means also the production and designing of “bio-artifacts”. Corn is a bio-artifact. But we have to learn to see degrees, nuances and be more specific in the kind of analysis that we make when we draw a border between the natural and the artificial.

El Banco de Germoplasma de Especies Nativas de Oaxaca (gene bank of Oaxaca’s native species). Photo courtesy of Arte+Ciencia

El Banco de Germoplasma de Especies Nativas de Oaxaca (gene bank of Oaxaca’s native species). Photo courtesy of Arte+Ciencia

El Banco de Germoplasma de Especies Nativas de Oaxaca (gene bank of Oaxaca’s native species). Photo courtesy of Arte+Ciencia

El Banco de Germoplasma de Especies Nativas de Oaxaca (gene bank of Oaxaca’s native species). Photo courtesy of Arte+Ciencia

In Europe, GMO are submitted to very strict regulations. The U.S.A. are notoriously far more favorable to GMOs. How is the situation in Mexico and what is the state of the debate about ‘native’ corn vs transgenic corn?

For the moment, there is a prohibition in Mexico to continue with the planting of transgenic corn, not even for experimental purposes, because it has been demonstrated that all our country has corn biodiversity, not only the south, and that therefore all the territory must be protected from contamination. Being also the center of origin of corn, puts us in the special condition of watching for biodiversity.

But it is very important to say, and we have previously demonstrated this, that we are importing corn seeds from the USA, some of them are transgenic and germinal. Non-human animals are being fed in Mexico with transgenic corn. There is not an adequate surveillance from the Mexican government in regard to the importation of these seeds. And since we are bound to buy corn to the USA, because of the NAFTA, and the USA is producing transgenic corn, we are very worried.

It can be said that there is no problem with transgenic food, but there is no consensus in the scientific community about this. And this should be enough to have more precaution. But I insist, what is at stake is not only the way in which we produce food and what for, but also how we dwell in this world, and what cultural diversity are we willing to preserve and respect.

The example of high fructose corn syrup allow us to see how things are related to each other in more profound and complex ways that what we usually are seeing. The production of this syrup has signified for Mexico a financial crisis regarding the sugar cane industry. The consumption of these products is also a health problem. Why are we eating everything so sweet? How and why have we changed so profoundly in the past century our relationship to the land, the planet, our bodies, our cultures, etc.? What does technology means seeing from this perspective?

How can art contribute to the discussions around the issue?

The nine pieces that we are presenting are dealing with many of the topics afore mentioned. BIOS Ex machinA: Serán ceniza, mas tendrá sentido ligeramente tóxico/ It will be ashes, but will make sense (slighty toxic). Is an experiment to detect contamination of transgenic corn in seeds in Mexican soil. We test the resistance to the herbicide glyphosate or Roundup produced by Monsanto.

BIOS Ex machinA: Serán ceniza, mas tendrá sentido ligeramente tóxico

BIOS Ex machinA: Serán ceniza, mas tendrá sentido ligeramente tóxico

BIOS Ex machinA: Serán ceniza, mas tendrá sentido ligeramente tóxico

BIOS Ex machinA: Serán ceniza, mas tendrá sentido ligeramente tóxico

BIOS Ex machinA: Polinización cruzada/Cross-pollination is a video documental that presents interviews to different actors in the current debate regarding transgenic corn in Mexico. It exhibits the capacity of the discourse to say true or to lie.

BIOS Ex machinA: Polinización cruzada

BIOS Ex machinA: Polinización cruzada

BIOS Ex machinA: Desde adentro. Experiments in situ to teach the reaches and limites of DIY biology.

BIOS Ex machinA: Desde adentro

BIOS Ex machinA: Desde adentro

Arcángel Constantini and Marcela Armas working with BIOS Ex machinA: Milpa polímera/Polymer milpa. Is a robot-3D printer that prints PLA in form of

corn seeds. The ultimate degree of industrialization of corn, is use it to produce plastics.

Marcela Armas and Arcángel Constantini, Milpa polímera

Marcela Armas and Arcángel Constantini, Milpa polímera

Marcela Armas and Arcángel Constantini, Milpa polímera

Marcela Armas and Arcángel Constantini, Milpa polímera

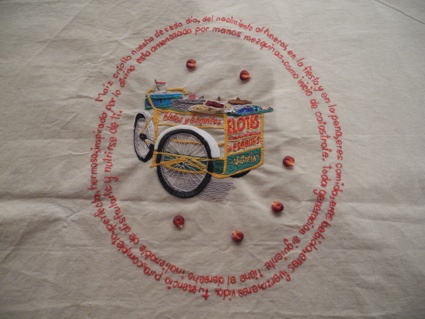

Lena Ortega‘s La dulce vida/La dolce vita deals with the problem of high fructose corn syrup, the way in which families are fed nowadays, and the transformation from the rural world to the cities.

Lena Ortega, La dulce vida

Lena Ortega, La dulce vida

Alfadir Luna’s Containers reflects about the problem of transforming corn into a commodity that is being transported in containers along with fuel, concrete, steel, etc.

Alfadir Luna, Container

Alfadir Luna, Container

Collective MAMAZ. Códice del maíz exhibits textiles that tell the story of what corn represents to local women in Oaxaca and in other places of Mexico.

Colectivo MAMAZ, Códice del maíz

Colectivo MAMAZ, Códice del maíz

Colectivo MAMAZ, Códice del maíz

Colectivo MAMAZ, Códice del maíz

Collective Zm_maquina Media Lab: Installation that senses the respiration (production of CO2) of corn plants and engraves a copper disc with this data.

Collective Zm_maquina Media Lab

Collective Zm_maquina Media Lab

Minerva Hernández and Héctor Cruz: Zea mays. Installation that reflects on how the corn plants are altered by the presence of humans.

Minerva Hernández and Héctor Cruz, Zea mays

Minerva Hernández and Héctor Cruz, Zea mays

Minerva Hernández and Héctor Cruz, Zea mays

Minerva Hernández and Héctor Cruz, Zea mays

I read in an online article that visitors will be able to work with scientists to determine whether a corn is transgenic or not. Could you tell us more about the setting and the participation of the public?

There are two possibilities for actual interaction of the public with the exhibition. The day of the inauguration we set a lab of DIY biology. We wanted to show to the public how to extract a DNA molecule out of a corn seed. Also, we wanted to show how to do a process of electrophoresis and of replicating DNA with a PCR. For this we used DNA from E. coli.

The other possibility is bringing corn seeds to the museum. Here we will plant them and grow them to test the resistance to Roundup. In case that we have resistance to the herbicide, we will take the surviving plants to the lab, to test if they are transgenic or not.

The exhibition seems to feature works in which artists have collaborated with scientists and engineers. Was this art/science collaboration one of the main thread of the curatorial process? How did you select the artworks that participate to the exhibition?

This exhibition has an important antecedent in a previous one, Sin origen/Sin semilla (Without origin/Seedless) that we presented in 2012-2013 in the museums MUCA Roma and MUAC at UNAM in Mexico City.

We have been working with scientists, engineers, artists, scholars, students, editors, designers, etc. We strongly believe that the interdisciplinary work is the way to approach complex issues, because it permits a wide perspective that can relate different layers. This is how we have been working on the issue of corn, and so far we have very good results.

In the group Arte+Ciencia (Art+Science) based at UNAM we have been building a path to intertwine arts, science and humanities.

Thanks María!

All images courtesy of Arte+Ciencia.