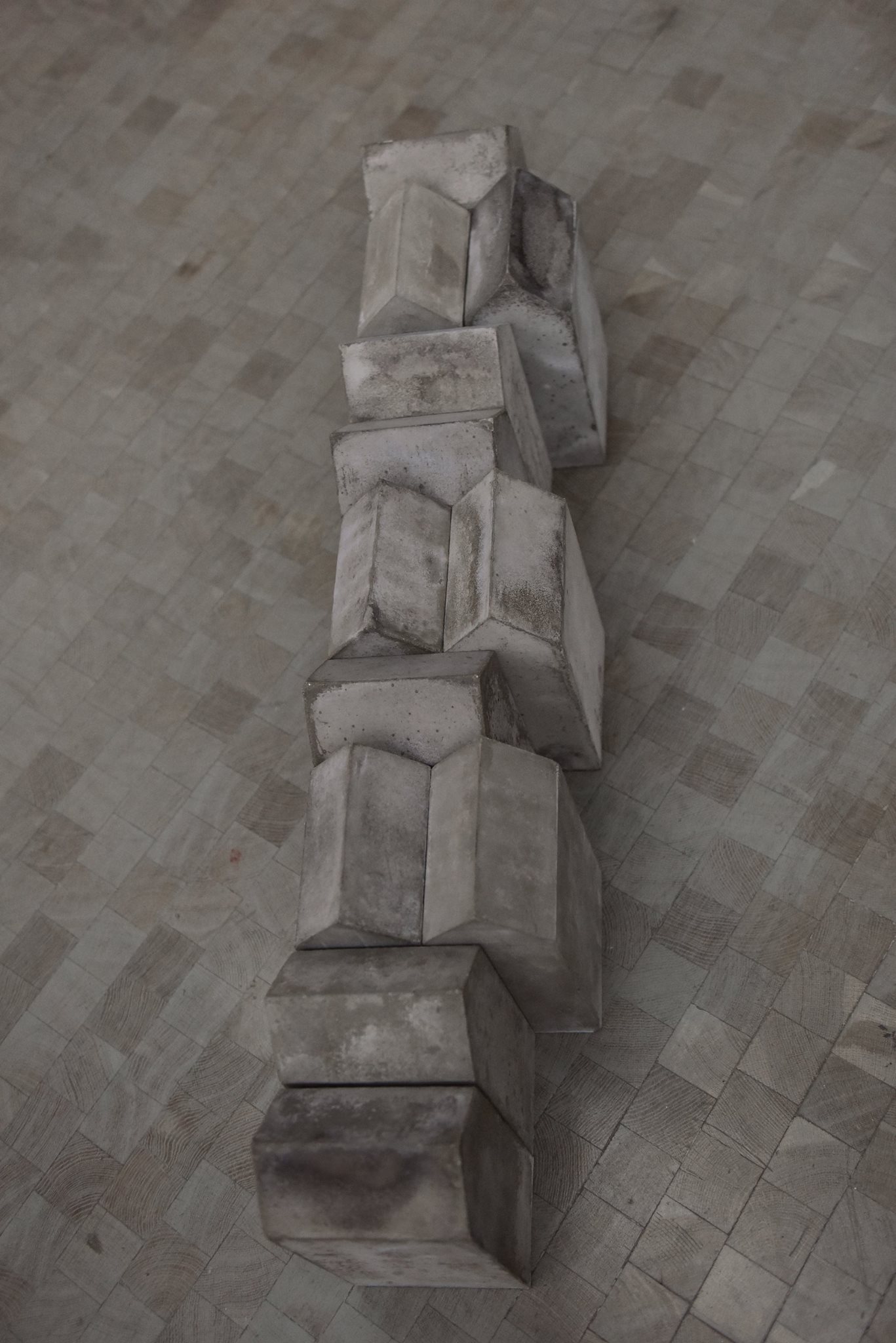

Werner Feiersinger, Untitled (Corviale), 2015

Long reviled, brutalism seems to be everyone’s favourite architectural style at the moment. The nostalgia for the late modernist architecture manifests itself through stunning coffee table books, brutalism appreciation society and plenty of campaigns to save some of its masterpieces.

If the rude charms and resolute geometries of brutalism have been somewhat rehabilitated, its utopian ambitions have not. Buildings made of the cement and stone amalgam still carry with them the stigma of the egalitarian commitments and social advances they promised but spectacularly failed to deliver.

Ron Terada, Concrete Language, 2006/2016

Instead of enriching people’s lives with carefully proportioned dwellings and safe green space for socializing, the structures ghettoised the poor and betrayed their top-down (if well-meaning) designs.

Béton, an exhibition that opened a few months ago at Kunsthalle Wien, is entirely dedicated to brutalism. Its title alludes to the etymology of the architectural movement: béton brut, which can be translated into ‘exposed concrete.’

The show doesn’t intend to debate on the merits and shortcomings of concrete and its uses in building and engineering. Instead, it invites us to revisit the radical ideas and social utopia that these working-class housing and public buildings attempted to embody .

Aiming to change society, brutalist architecture virtually gave shape to utopia. Today, many of the buildings built at the time are threatened with demolition; they are considered to have failed their purpose. In light of a modernism stained by dystopia, contemporary art once again carve out its original ideas, its euphoria, but also its failure. Not out of a nostalgic longing but for the sake of remembering that architecture was once more than enclosed space, and concrete was not merely a building material but was historically and ideologically charged.

While i was in town to visit AJNHAJTCLUB at Q21, i crossed the square of the MuseumsQuartier and spent a couple of hours walking through the Béton exhibition…

Liam Gillick, Pain in a building, 1999

The UK has its fair share of brutalist estates and buildings that didn’t live up to the democratizing aspirations of their architects and planners. Thamesmead in Greater London is a good example of what happens when commendable utopia has to contend with economic realities. Conceived in the 1960s as the town of the future, Thamesmead promised to combine city life with the joys of the countryside: green spaces, a nature reserve and an artificial lake. However, the experiment quickly turned sour. Plans to build a shopping center around a marina, a train station and other amenities had to be scrapped because of financial difficulties. Criminality rose quickly and in the late ’70s, the neighbourhood was used as a sink estate by the councils around.

Stanley Kubrick filmed some of the key scenes of his 1971 film A Clockwork Orange in Thamesmead. The town served as the setting for a dystopic London ruled by anarchy and violence.

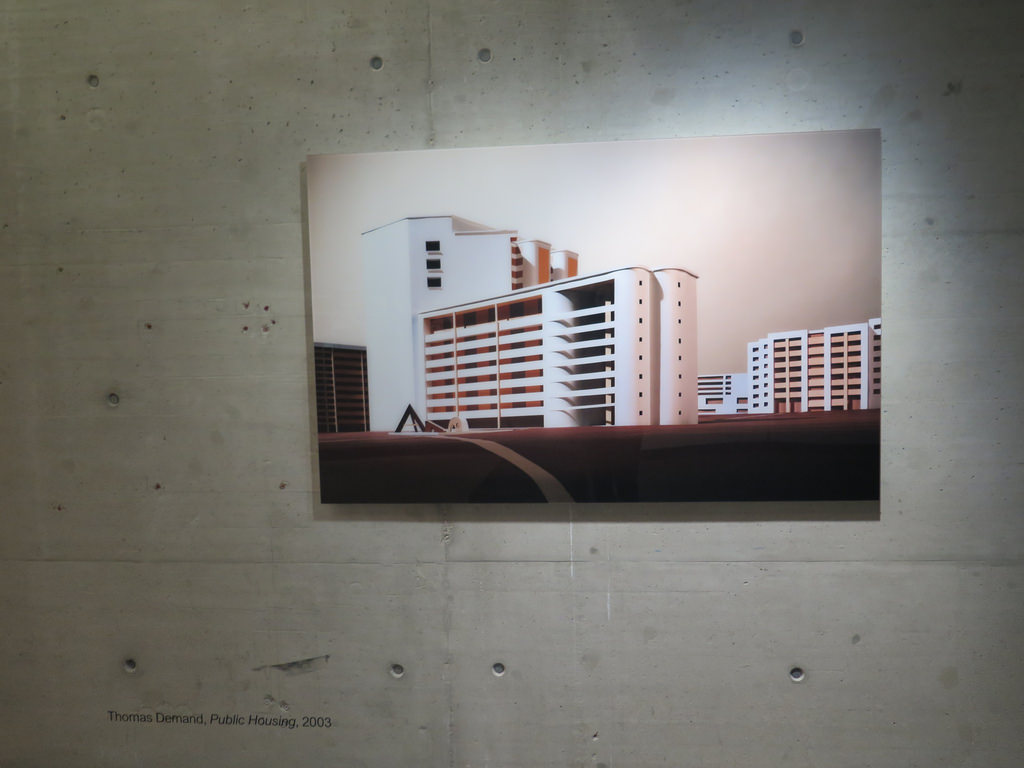

Thomas Demand, Public Housing, 2003

Public Housing, by Thomas Demand, demonstrates that not all good intentions end up in embarrassment and disappointment.

Before taking the photos, Thomas Demand builds by hand paper and cardboard models based on pictures. The original image for “Public Housing” is printed on the pink $10 banknote from Singapore. The housing estate is typical of the low-cost, high-rise housing blocks built in 1965 when Singapore gained its independence from Malaysia and decided to address the poor living conditions and housing issues. By 1965 the percentage of the local population living in public housing rose from 9% in 1959 to 23%. Roughly 80% of Singaporeans now live in flats built by the Housing and Development Board of Singapore, a city-state usually associated with finance rather than with policies that protect the underprivileged.

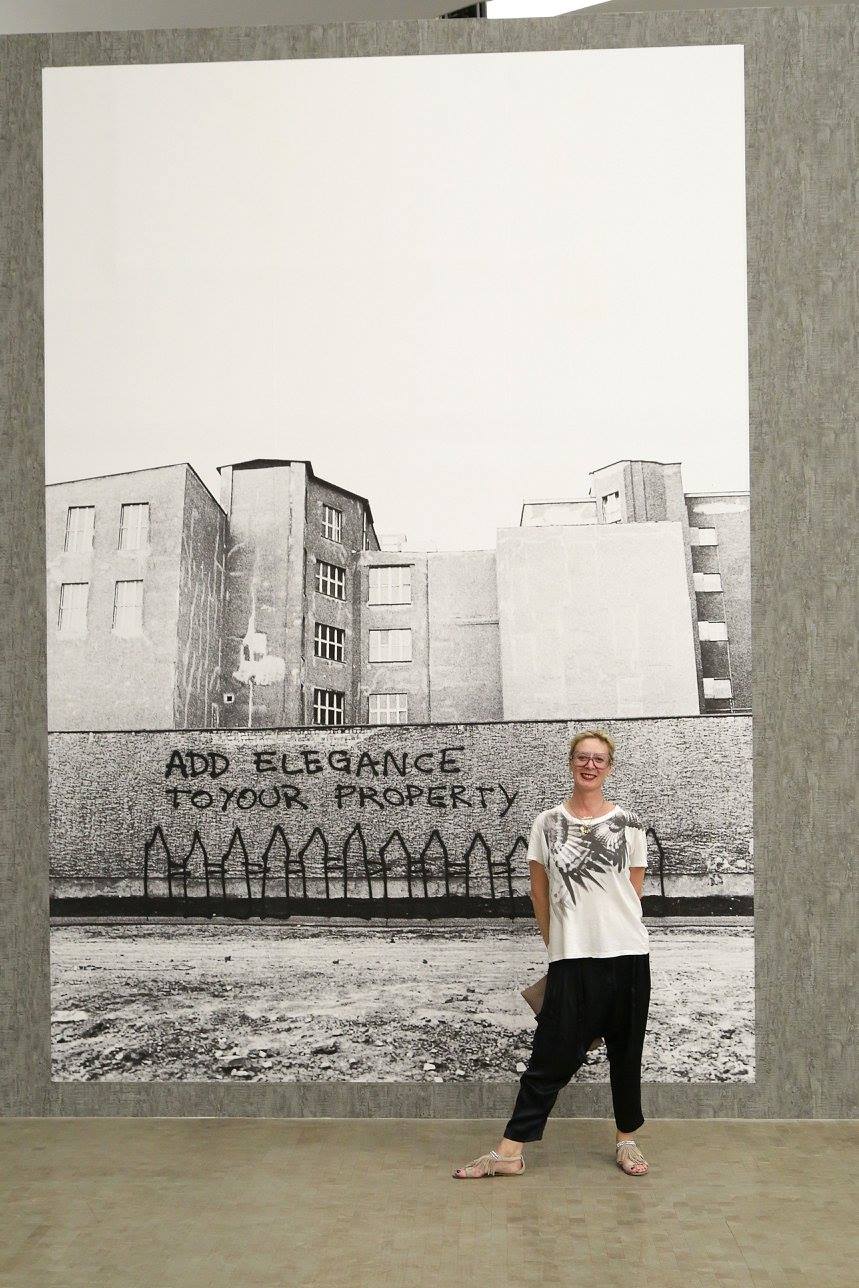

Monica Bonvicini, Add Elegance to your Poverty, 1990/2016. Opening of the exhibition. Photo: Joanna Pianka (eSeL.at) for Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier

Monica Bonvicini‘s “Add Elegance to your Poverty” questions cynical approaches to real problems. Sprayed on a wall in Berlin, the sentence is a direct reference to an advertising claim which is often used to sell real estate in California: “Add Elegance to Your Property”. It also echoes the famous “Arm, aber sexy” (poor but sexy) coined by Berlin’s former mayor Klaus Wowereit in an attempt to gloss over the city’s budget deficits.

Miki Kratsman, Abu Dis 2003, 2003. Photo: Chelouche gallery

Israel’s self-defence law requires the installation of shelters in all buildings, including private houses. It also regulates the upkeep of bunkers in homes and factories. After the First Gulf War, steel concrete with access to the individual flats within a building were also added, providing thus easy access to a space of safety in case of chemical weapon attacks by neighbouring countries. Miki Kratsman’s photos show how these safe rooms are integrated into the urban landscape, outsiders would find it difficult to identify these shelters as structures created for situations of violence.

The intentionally unsensational view of these extremely politically and socially charged elements of the urban landscape alludes to the omnipresence of this conflict, precisely because of the incidental nature of Kratsman’s approach.

Kratsman also documented frontier posts along the Road 443. Although the road partly leads through Palestinian territory, it is only accessible to Israeli. In 2002, Israel prohibited Palestinians from using the road, by vehicle or on foot, for whatever purpose, including transport of goods or for medical emergencies.

I couldn’t find photos of either series online so i’ve picked up another one to illustrate his work.

Ingrid Martens, Africa Shafted, 2012

Ingrid Martens, Africa Shafted (trailer), 2012

Ingrid Martens, Africa Shafted (trailer), 2012

Ingrid Martens spent 5 years filming people who live in Ponte Tower, ‘the tallest and grandest urban slum in the world’. Conceived as a luxury residential complex for white people living in Johannesburg in the 1970s, the brutalist tower is built around a hollow inner core that provides light thanks to the windows that encircle the inner and outer exterior.

In the 1990s, the area surrounding the 54-storey building started to be associated with gang crimes. Most of the white privileged families moved to supposedly safer suburbs and the owners of the building left it to decay. Soon, South Africans of colour, as well as immigrants from neighbouring countries, moved in. The residential block grew to become densely populated, and acquired the reputation of being a ghetto. Today, after renovation and tightened security, the situation at Ponte is considered to have greatly improved.

Africa Shafted is a fascinating documentary that takes us on a ride up and down one of the lifts of the building. Documentary maker Ingrid Martens has the residents talk to the camera but most importantly talk to each other. They discuss the bad reputation of the building, the joy of living in an apartment that overlooks the whole city, the political and economic reasons why some of them had to leave their own country, the prejudices they encounter in their adopted country, etc.

The multitude of voices on African issues portrays a metaphor of Ponte as “Little Africa”, providing perspectives that not only cover the problems and dreams of prosperity of the continent, but poignant as well as provocative opinions on contemporary life.

Werner Feiersinger, Untitled (Morandi), 2010

Opening of the exhibition. Photo: Joanna Pianka (eSeL.at) for Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier

Werner Feiersinger, Untitled (Fregene), 2015

Werner Feiersinger, Untitled (Musmeci), 2015

Werner Feiersinger’s series of shots of Italian buildings from the 1950s to the 1970s reminds us of the power and audacity of the architectural applications of futurism. Even left to decay, these example of post-war architecture demonstrate that sometimes the past can be more radical than the present.

Dante Bini’s concrete domes, which were constructed with the help of moored balloons, are juxtaposed with shots from the ten-storey housing complex Corviale on the outskirts of Rome, and Vittorio Giorgini’s expressive concrete summer house in Baratti. The designs of these structures of the 1960s and 1970s reflect the emphatic commitment to a cosmopolitan society. This undeniably experimental architecture is defined by vitality and lightness, and bears testimony to the economic and cultural upswing in a time characterised by the belief that the future could be shaped with architectonic means.

Tercerunquinto, Gráfica reportes de condición, 2010–2016. Installation view: Béton, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Tercerunquinto, M-19 (Gráfica reportes de condición), 2010

Tercerunquinto‘s photo series Gráfica reportes de condición is a collection of so-called status quo reports (reportes de condición). The Mexican artist collective commissioned a specialist on restoration and structural preservation, and a group of students, to produce reports on the condition of graffiti throughout the city of Bogotá and in particular the ones that protest against social inequality and governmental misdeeds: “no more state terror”, “Neither your, nor my government”, “When hunger is the rule, rebellion is a right”, “Don’t vote – there is no space for our dreams in your ballot boxes.”

The slogans were then printed onto photographs of Bogotá in which the degree of social discontent is generally reflected in the urban landscape.

As in many countries, the public sphere is the billboard for those who wish to mobilise like-minded people or to express their dissatisfaction with existing circumstances. Like ethnologists of everyday life, Tercerunquinto commission inventories in order to study the interrelationship between society and urbanity.

Jumana Manna, Government Quarter Study, 2014; Mark Boyle, Secretions: Blood, Sweat, Piss and Tears, 1978. Installation view: Béton, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Jumana Manna’s sculptures are full size replicas of three concrete pillars found at the entrance of the Høyblokka (“H-Block”), a brutalist building located in Regjeringskvartalet, the government quarter in Oslo. Built in 1958, in a period of Post War optimism and aspirations of the Nordic model of the Welfare State, the building was partly destroyed in 2011 in the Norway attacks orchestrated by right-wing extremist Anders Breivik.

Following the bombing, the decision whether to preserve or demolish the Høyblokka and a building in the same quarter is at the center of an emotionally intense national debate.

Tobias Zielony, Le Vele di Scampia, 2010

Tobias Zielony, Le Vele di Scampia, 2010

Le Vele di Scampia is the popular name of a Brutalist housing complex in Naples made famous by the movie Gomorrah which used some of the district as its backdrop. Designed between 1962 and 1975 in brutalist style, the gigantic building complex was supposed to provide families with functional facilities for life in a residential community but it has long been controlled by the Mafia. With over 50% unemployment, the area has a very high crime rate and is considered to be one of Europe’s biggest drug dealing venues.

In Tobias Zielony‘s part social documentation part artistic experiment images, night shots of the architecture are interrupted by portraits of young people.

More images from the exhibition:

David Maljkovic, Missing Colours, 2010

Opening of the exhibition. Photo: Joanna Pianka (eSeL.at) for Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier

Opening of the exhibition. Photo: Joanna Pianka (eSeL.at) for Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier

Olaf Metzel, Treppenhaus Fridericianum, 1987. Opening of the exhibition. Photo: Joanna Pianka (eSeL.at) for Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier

Olaf Metzel, Treppenhaus Fridericianum, 1987. Opening of the exhibition. Photo: Joanna Pianka (eSeL.at) for Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier

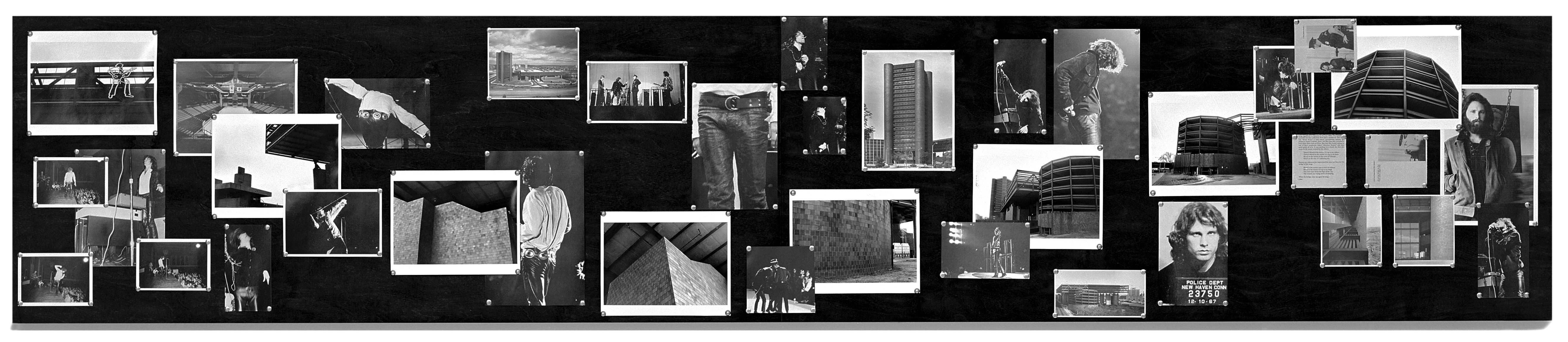

Tom Burr, Brutalist Bulletin Board, 2001

Hubert Kiecol, Zeile, 1981. Opening of the exhibition. Photo: Joanna Pianka (eSeL.at) for Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier

Hubert Kiecol, Zeile, 1981. Installation view: Béton, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Installation view: Béton, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Installation view: Béton, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Andreas Bunte, Still from O.T. (Kirchen), 2012

Kasper Akhøj, 999, 2015

Béton, curated by Nicolaus Schafhausen and Vanessa Joan Müller, is at Kunsthalle Wien until 16 October 2016. The exhibition guide is available for download in PDF format.

Every Saturday, urbanist Eugene Quinn invites locals and tourists to Vienna ugly, a guided tours of Vienna’s most unattractive squares .

Related stories: Utopia London, Brutal and Beautiful: Saving the Twentieth Century, Balkanology, New Architecture and Urban Phenomena in South Eastern Europe.