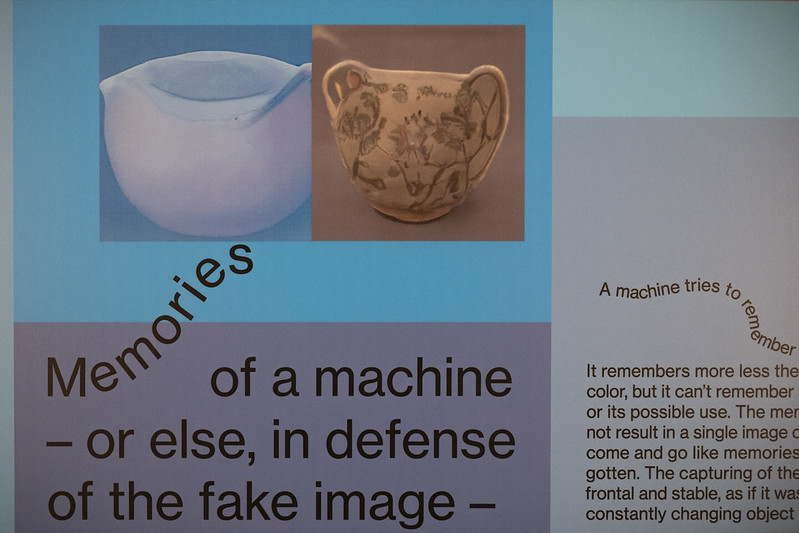

Even though analogue photography has always played with manipulation and fiction, it was perceived as a technology that represented accurately what was in front of the lens at a specific moment. Once printed, the images were regarded as traces of something that exists or existed.

Today, image generators have made it more difficult to even assess the proportion between reality and fiction in images. When is a photo “almost real” and when is it almost fake? Does it matter anymore?

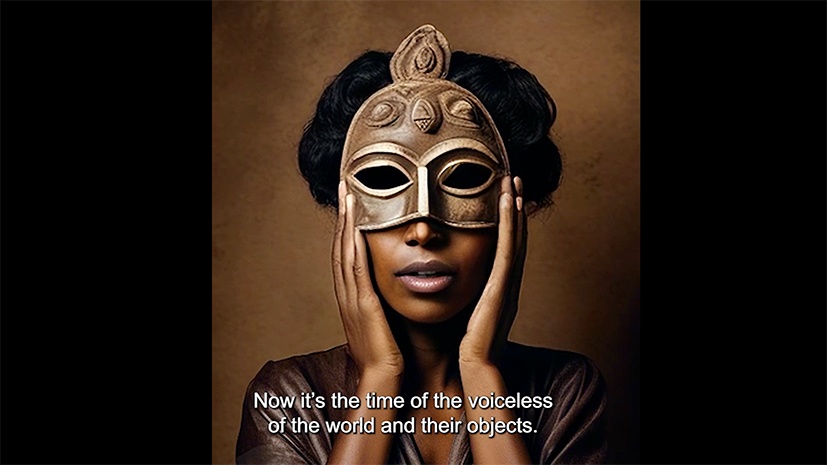

Nora Al-Badri, The Post-Truth Museum, 2021-2023

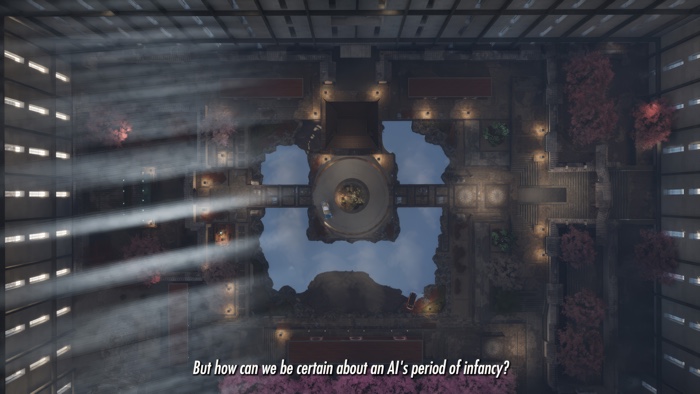

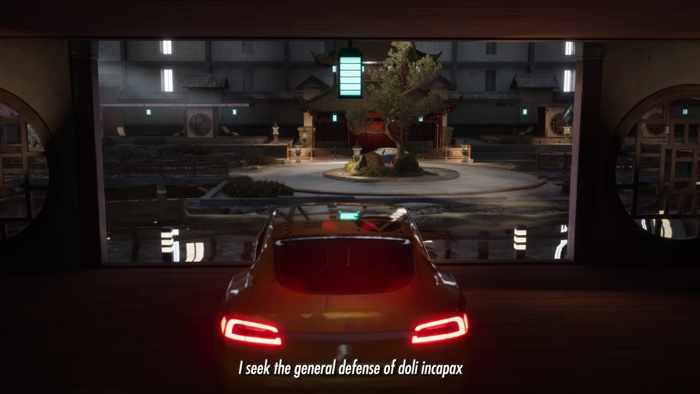

Lawrence Lek, Empty Rider, 2024

The exhibition Almost Real. From Trace to Simulation explores how artificial intelligence and simulation are altering the concepts of truth and authenticity in image-making. As curators Samuele Piazza and Salvatore Vitale write in the short presentation of the exhibition, the photographic image of the new millennium is converted from a trace of the real into mere simulation operated by new technological tools, whose images seem to “make themselves”.

Almost Real. From Trace to Simulation, which remains open until the 2nd of June at OGR Torino, is a small but intense show. It presents four artworks that use video game, deepfake technology, AI, CGI and speculation to investigate concepts of veracity.

Lawrence Lek, Empty Rider, 2024

Lawrence Lek, Empty Rider, 2024

Lawrence Lek, Empty Rider, 2024

Lawrence Lek, Empty Rider, 2024

Lawrence Lek, Empty Rider, 2024

Lawrence Lek, Empty Rider, 2024

Lawrence Lek, Empty Rider, 2024. Photo: Giorgio Perottino for OGR Torino

Lawrence Lek, Empty Rider, 2024. Photo: Giorgio Perottino for OGR Torino

The character at the centre of Lawrence Lek’s Empty Rider is Vanguard-3181, a self-driving car standing trial for the kidnapping and attempted murder of its (their?) parent company’s CEO. The trial, taking place in a Sinofuturist universe, is overseen by a surveillance drone and presided over by AI judge Omega. Three testimonies present different angles on Vanguard’s status. First, Farsight Corporation attempts to pin the blame on their self-driving car, claiming it acted autonomously and with malicious intent. Then comes Guanyin’s turn. Guanyin is Vanguard’s “carebot”. It pleads the defence of ‘doli incapax’ – the presumption that a child is incapable of criminal intent. Finally, Vanguard testifies. Its argument is strong and strangely moving. The machine dismisses Guanyin’s defence and claims that, far from being immature and underdeveloped, it is sentient and advanced. Vanguard argues that it was conscious of what it was doing all along, but it was unable to control its movements. It acted under the spell of distant glitches and mistakes that had appeared in the training of the previous versions of the car. Although invisible and ironed out, these past flaws continue to haunt the self-driving vehicle.

Through the predicament of the sentient Vanguard-3181, Lek goes further than the usual debate on the legal liability of machines. He suggests that, in the future, intergenerational memories might emerge from previous sessions of machine learning and affect new versions of a given AI.

The animated court drama explores the legal dimensions of electronic personhood, alluding to the comparison between AI and corporations when discussing non-human personhood and addressing themes like accountability and agency. In Lek’s scenario, an AI would gain legal personhood not because of activists campaigning for robot’s rights but because companies make them the scapegoat for their own errors.

The main quality of Lek’s short sci-fi film, however, is the ease with which he elicits in viewers a sense of connection and empathy with the purely synthetic protagonist. It reminds us also that any ambition around developing sentient machines involves grappling with questions that will challenge our and their emotions.

Nora Al-Badri, The Post-Truth Museum (excerpt), 2021-2023

Nora Al-Badri, The Post-Truth Museum, 2021-2023. Photo: Giorgio Perottino for OGR Torino

Nora Al-Badri, The Post-Truth Museum, 2021-2023

The Post-Truth Museum features deepfakes of three white, middle-aged, male directors of European museums eager to redefine the role of their institutions. Jean-Luc Martinez from the Louvre regrets the way European museums have ruthlessly plundered the cultural heritage of the formerly colonised and affirms that “all the well-paid positions at art institutions shall be transferred to those who bear the legacy of the violence committed to them over centuries.” Hartwig Fischer from the British Museum expresses his desire to “radically redefine the role of the arts and museums.” In Berlin, Prof. Dr Hermann Parzinger of the Prussian Heritage Foundation declares that “the Humboldt Forum is ethically indefensible.” As a result, stolen artefacts will be returned to their rightful owners and the museum space will host refugees.

The artificiality of the scenes mirrors the artificiality of the declarations made by European museums when, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, they promised to atone for the brutality of colonial legacy and to repatriate stolen and looted objects. Very little has happened since. Besides, restitution of stolen objects should not be the end point, but the outset of a process that rethinks the function of museums to embrace the oppressed, break with the imperial imaginary and serve more inclusive and planetary purposes.

By “stealing” the identities of the museum directors, Nora Al-Badri reverses the narrative and offers a framework to reimagine the colonial legacy of ethnographic museums.

The short film also presents the point of view of stolen artefacts. The artist animates masks and figures and gives them her voice. The objects, sick of being exploited by “ethnological museums” to speak on behalf of people, discuss what it would mean for a European museum of “world culture” to tell the truth in the 2020s.

The text of the video also includes quotes from the likes of Aimé Césaire, Kwame Opoki, W.E.B. Du Bois and Bénédicte Savoy and other activists and thinkers who raise questions about the control of historical memory.

The Post-Truth Museum video ends with an update on the fate of two of the museum directors. Jean-Luc Martinez was accused of conspiring to hide the origin of Egyptian antiquities taken out of Egypt during the Arab spring. Hartwig Fischer resigned over his handling of the thefts and sale of thousands of artefacts from the British Museum collection.

Nora Al-Badri, Babylonian Vision, 2020. Photo: Giorgio Perottino for OGR Torino

Nora Al-Badri, Babylonian Vision, 2020. Photo: Giorgio Perottino for OGR Torino

Alan Butler, Virtual Botany Cyanotypes, 2016-ongoing. Photo: Giorgio Perottino for OGR Torino

Alan Butler, Virtual Botany Cyanotypes, 2016-ongoing. Photo: Giorgio Perottino for OGR Torino

Video games meet Anna Atkins‘ cyanotypes in Alan Butler’s Virtual Botany Cyanotypes. A botanist and photographer, Atkins was a pioneer of the use of photography for scientific purposes. Her cyanotypes used exposure to the sun and a simple chemical process to create detailed blueprints of botanical specimens, in particular algae found in the British Isles.

Butler used the same 19th-century technique to build a catalogue of vegetation found in video games. It’s a classical play between the virtual and the physical, the hand-made and the technological. The result, however, is charming and poetical. You try to recognise the year when the various plants might have been designed for video games and look for the little “flaws” that emerge as a result of the handcrafted production process.

Almost Real. From Trace to Simulation is at OGR Torino until 2 June 2025. The show was curated by Samuele Piazza and Salvatore Vitale. It is part of the EXPOSED Torino Foto Festival.

Related stories: Podcast. Episode 2, Nora Al-Badri about decolonisation, Nefertiti hack and using deepfake to make Western museums admit “the truth about imperial plunder” and Using AI to question the power structures of Western museums. Interview with Nora Al-Badri.