A People’s Art History of the United States. 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice Movements, by artist and author Nicolas Lampert.

Publisher The New Press writes: Called “important” by renowned art critic Lucy Lippard, A People’s Art History of the United States introduces us to key works of American radical art alongside dramatic retellings of the histories that inspired them. Richly illustrated with more than two hundred black-and-white images, this book by acclaimed artist and author Nicolas Lampert is the go-to resource for everyone who wants to know what activist art can and does do for our society.

Spanning the abolitionist movement, early labor movements, women’s suffrage, the civil rights movement, and up to the present antiglobalization movement and beyond, A People’s Art History of the United States is a wonderful read as well as a brilliant tool kit for today’s artists and activists to adapt past tactics to the present, utilizing art and media as a form of civil disobedience.

Asco, Decoy Gang War Victim, 1974. Photo: Harry Gamboa Jr.

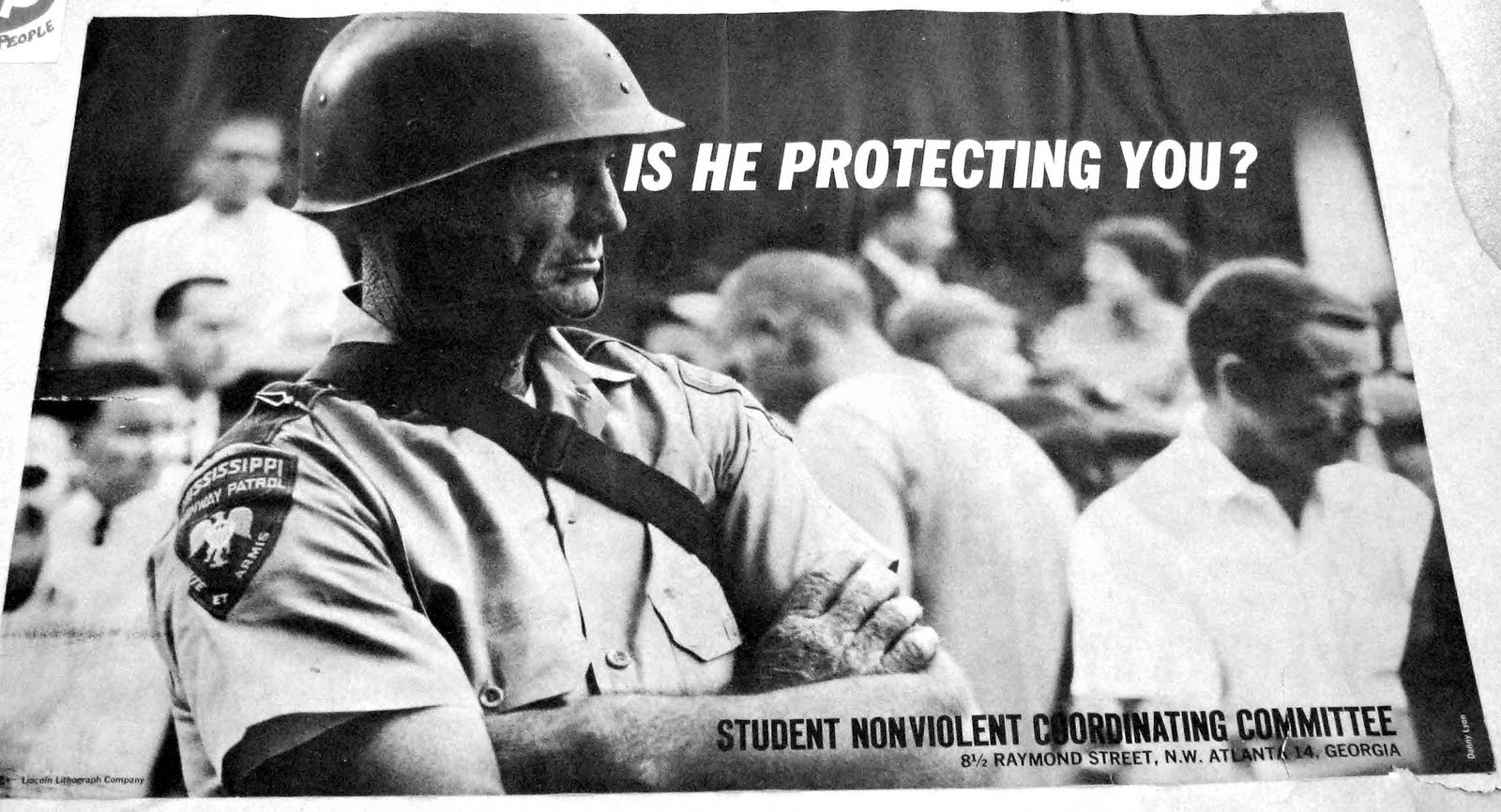

Danny Lyon, Poster—Is He Protecting You? Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee poster, about 1963

The book tells the history of artistic and popular resistance and recounts events that have changed society from the bottom up. Some of these events were initiated by activists who used visual tactics. Others by trained artists who joined a cause and anchored their art within an existing movement.

Each chapter zooms in on a specific political combat and explains with great details the tactics employed at the time by the activists. The tactics that triumphed but also the ones that flopped. Because it singles out specific political struggles instead of providing us with an all-encompassing survey of activism art, the book is also as an inspiring call to action for more artists to respond to contemporary crises and for more activists to use art in their interventions.

Nicolas Lampert is a talented writer and his book will take you on a memorable ride. One that goes from clergymen supporting the abolition of slavery to The Yes Men challenging unethical corporations. From women fighting for the right to have a say in politics to artists campaigning for museums and galleries to exhibit more women and people of color.

A People’s Art History of the United States is an invigorating book. It reminds us of the real impact that visual art can have on society, especially when it forgoes established art institutions, and roots itself in the communities and movements that push for social change. A book like this one is opportune and necessary at any moment in history and particularly in ours.

Stories, struggles and images discovered in the book:

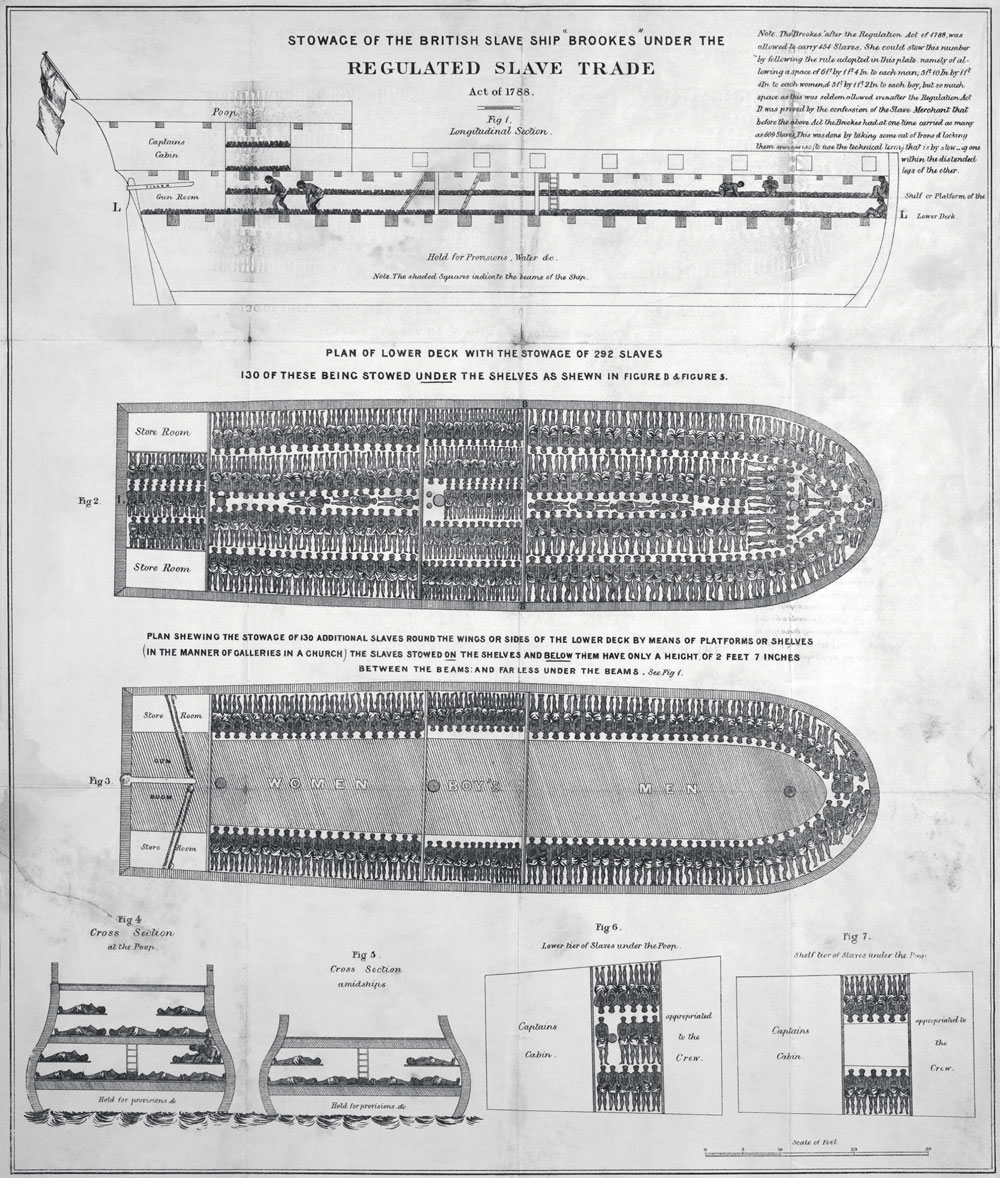

Description of the slave ship Brookes, 1788

In the late 1700s, abolitionists in England and USA used lithographs and illustrations in their fight against slavery. Their strategies differ though. In the USA, slavery was part of fabric of life and the campaigns there were more about moral persuasion. England had very few slaves on its soil so slavery was a more abstract concept for citizens.

In 1787, a young English clergyman called Thomas Clarkson started to investigate conditions of slave transport. He interviewed sailors, obtained equipment used on slave-ships, such as iron handcuffs, leg-shackles, thumbscrews, branding irons and even got seamen to testify before the Parliament. But it was an image that had the biggest political influence: the architectural rendering of the slave ship Brookes. Based on a detailed plan of a slave ship, he had an image drawn of chained black figures loaded on the ship, a view no English man could see when slave ships were docked in the harbours. The striking image was combined with texts that detailed the men’s ordeal, creating a sense of empathy for African slaves. London abolitionists had it printed on thousands of posters, and, in the years that followed, the diagram circulated in broadsheets, pamphlets and books in Scotland, France and the United States.

The graphic agitation produced results: the House of Commons passed the law against slave trade in 1792.

Richard Throssel, Interior of the Best Indian Kitchen on the Crow Reservation, 1910 (via Met museum)

Edward S. Curtis, Sioux chiefs, 1905

Another chapter looks at widely circulated historical photos that shouldn’t be taken at face value. The text brings side by side the works of white photographer Edward S. Curtis and the one of his contemporary, the lesser-known Native photographer Richard Throssel (Cree.)

Curtis portrayed Native people as untouched by white society, even though, at a time he was working, the reservation system and forced acculturation were firmly in place. Many of the scenes in his photos are staged, they erase any intrusion of modernity and perpetuate the ‘noble savage’ myth that people who bought his photos were so fond of. His images correspond more to what you would see in a Hollywood western film than to the reality of reservations.

Throssel, on the other hand, had been formally adopted by the Crow and his images of the tribe are the ones of an insider to the culture. This, of course, gave him additional credibility. He did produce staged image as well though. But with another objective, the one to discourage traditional living habits that were thought to be one of the main causes of diseases. Although they belong to a federal campaign to address the spread of diseases, his images responded to immediate needs and acted as a form of community activism. By showing Natives into more modern settings, they also offer a more realistic portrait of the Crows than the ones made for white tourists.

These two examples of approaches show the importance of looking at social conditions, politics, funding and motives behind images.

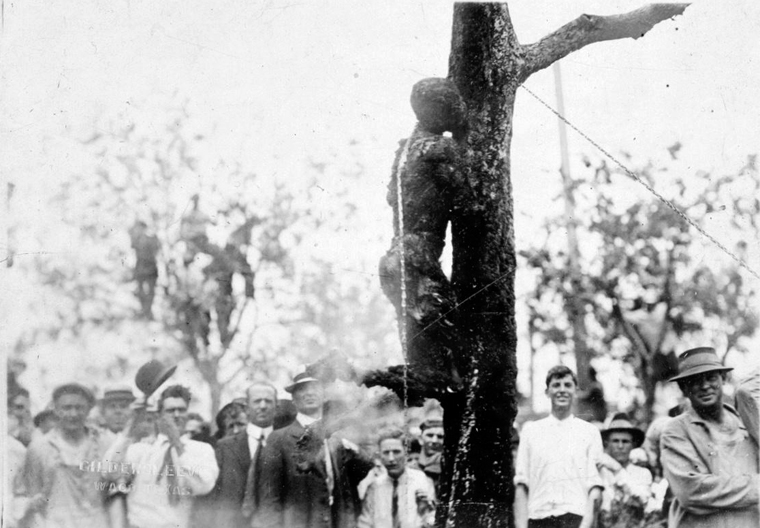

Jesse Washington, an African-American mentally handicapped teenager lynched in Waco, Texas, on May 15, 1916. He was accused of raping and murdering the wife of his white employer. Photo via DarkVictory’s fascinating flickr account

Another chapter zooms in on the personality of civil rights activist, author and editor W.E.B. Du Bois. The first African American to earn a doctorate at the University of Harvard, Du Bois was also one of the co-founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909.

Du Bois fought against a society characterized by segregation. At the time, the black working class was seen as a threat to the economic well-being of white working class and its members were demonized as being rapists.

This climate led to race terrorism, and in particular to lynch mobs that threatened African Americans, Jews, gay people, immigrants, catholics, radicals, labour organizers, etc. Some 4,742 people were lynched in US between 1882 and 1968. The vast majority of them were black.

Du Bois aimed to change the situation through the NAACP publication The Crisis. Progressive ideas were not only communicated through articles but also by photos showing successful African American businessmen, college graduates and other images aimed at uplifting the spirit of African Americans. The publication also printed horrific drawings and photos of African Americans being lynched. The images were accompanied by eyewitness accounts that aimed to provoke the federal government to eradicate the crime.

Du Bois also organized public actions such as large scale parades, silent demos, and the boycott of D.W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation which portrayed black men (some played by white actors in blackface) as half-wits and sexual predators.

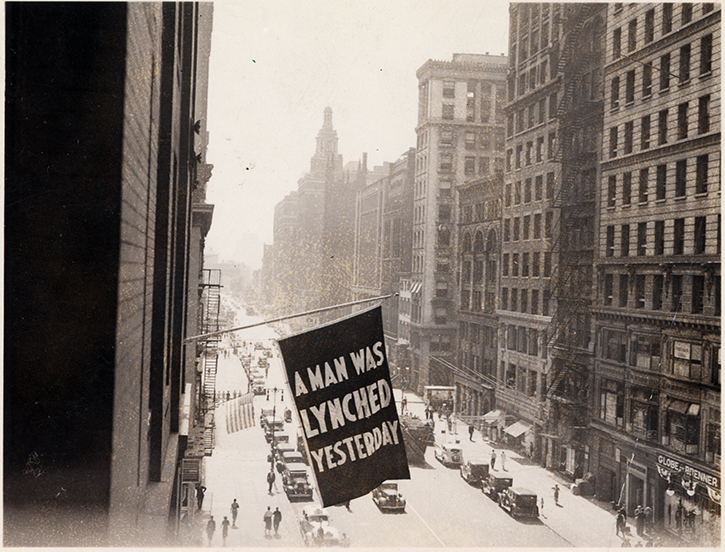

Lynching flag flying at NAACP headquarters, ca. 1938. NAACP Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Along with the anti-lynching campaign, in 1920 the NAACP began flying a flag with the words “a man was lynched yesterday” from the windows of its headquarters in New York city when a lynching occurred. Threatened to lose its lease, the NAACP had to discontinue the practice in 1938.

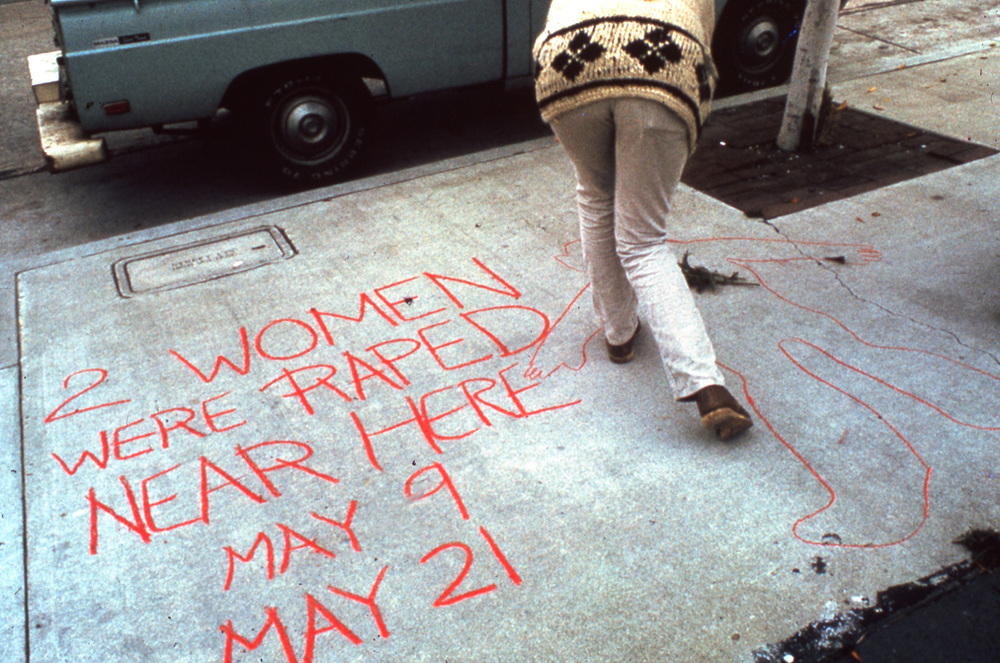

Suzanne Lacy, Three Weeks in May exposed the extent of re- ported rapes in Los Angeles during a three-week performance in May, 1977

ASCO, First Supper (After a Major Riot), 1974. Photo: Harry Gamboa Jr.

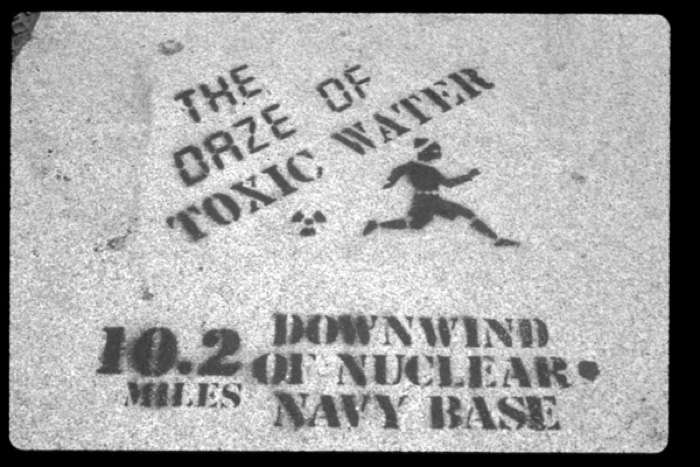

John Fekner, Groundwork: The Anti-Nuke Port Stencil Project, 1988. Image via justseeds

Iraq Veterans Against the War, Operation First Casualty, San Francisco, 2008

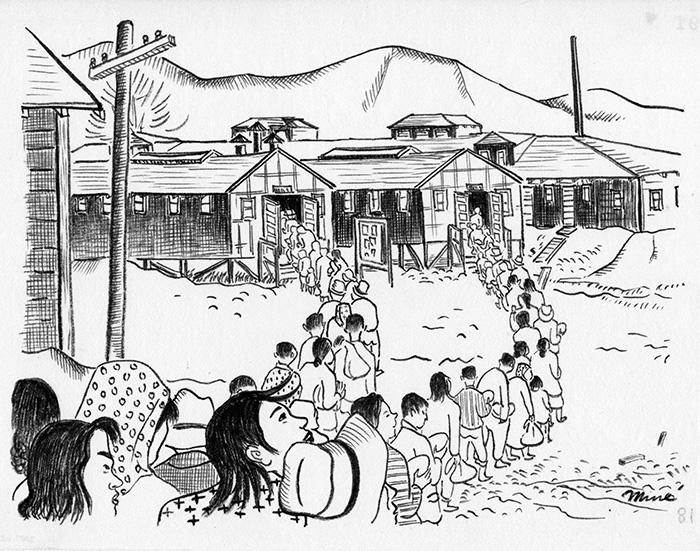

Miné Okubo, Waiting in lines, Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno, California], 1942. Part of Citizen 13660, a collection of 189 drawings and accompanying text chronicling the artist experience in Japanese American internment camps during World War II

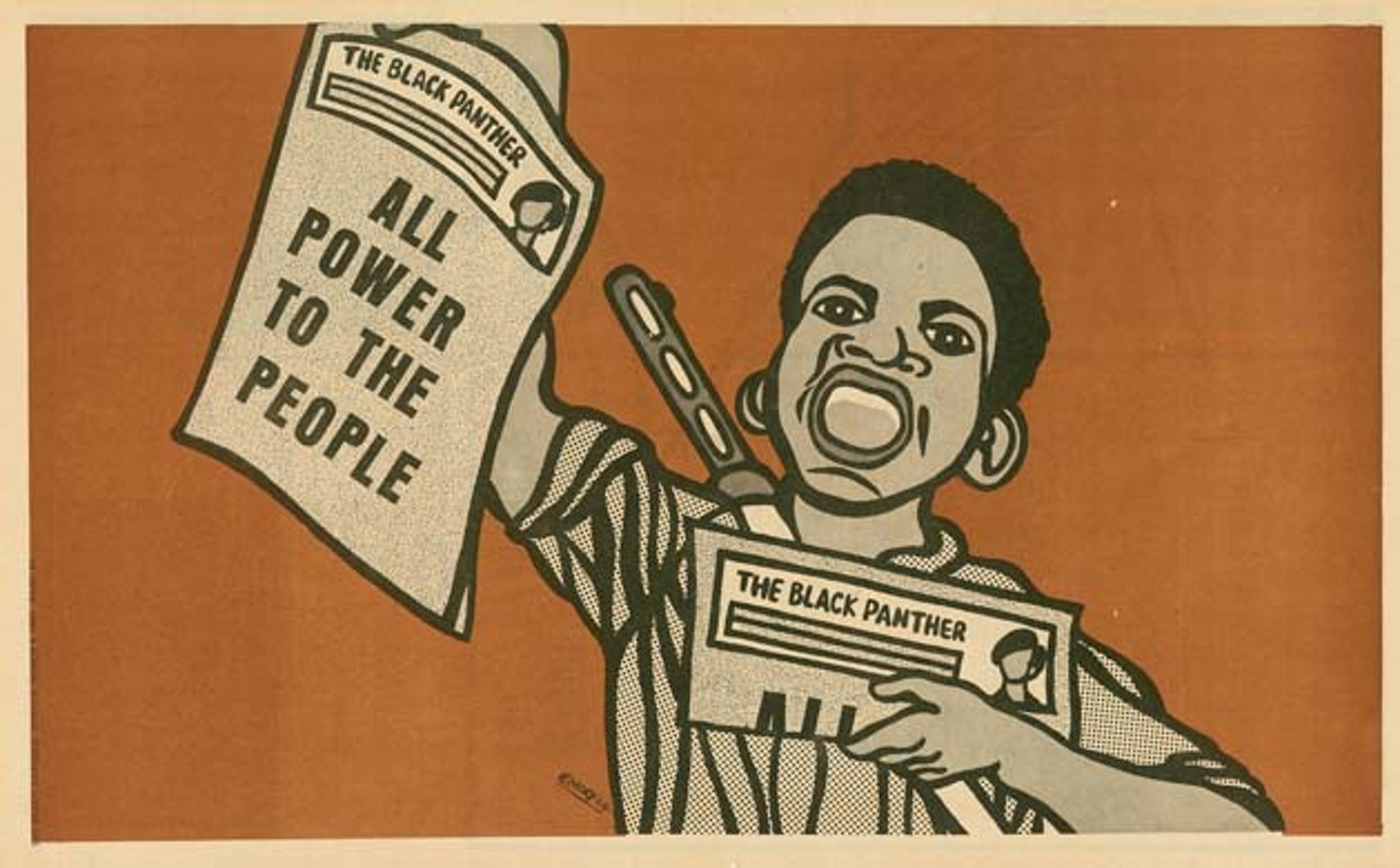

Emory Douglas, Minister of Culture and revolutionary artist for the Black Panther Party, March 9 1969: ‘All Power to the People’

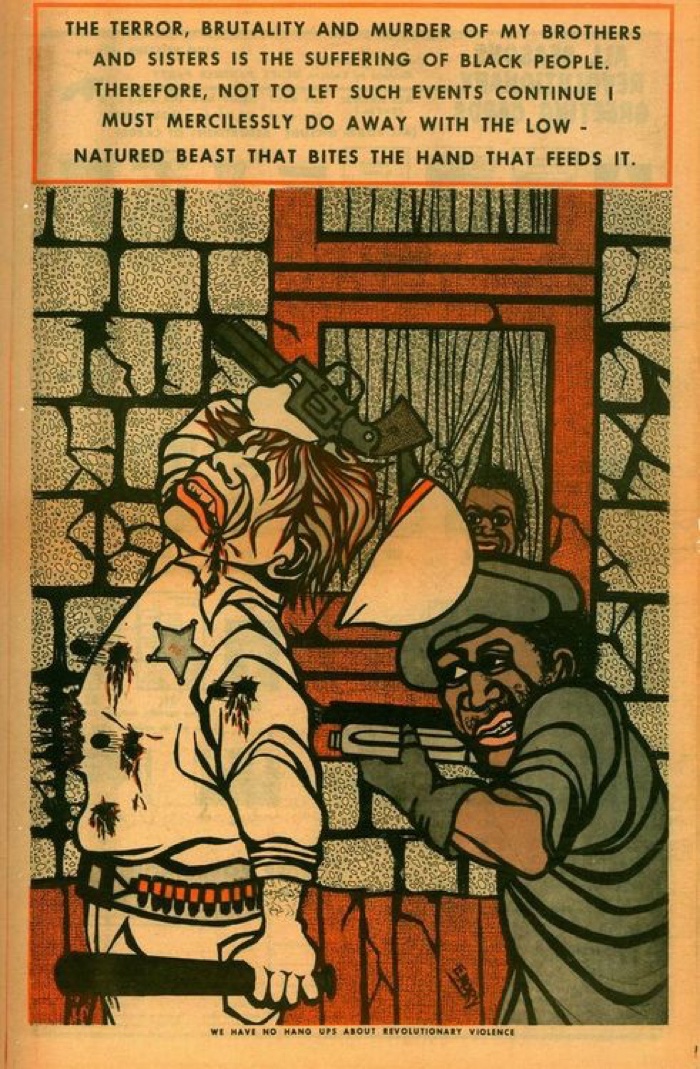

Emory Douglas, poster from The Black Panther, December 19, 1970, (copyright 2013 Emory Douglas/Artists Rights Society [ARS], New York