Whenever i’m in Amsterdam i head to Foam, the city’s museum of photography. Out of habit mostly. I actually think that Huis Marseille‘s programme is often bolder and more relevant to my own interests but this month Foam has a show titled Primrose – Russian Colour Photography and the word “Russia” always does it for me. The exhibition charts Russia’s attempts to produce coloured photographic images from the 1860s to 1970s. Room after rooms, the visitor realizes that photography is a cogent filter to reveal the history of a country in the course of a century.

Dmitry Baltermants, Men’s talk, 1950s

Dmitry Baltermants, Men’s talk, 1950s

Photo of the exhibition opening © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

Photo of the exhibition opening © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

You can read a text written by curator Olga Sviblova over here. It presents with great clarity the changes in technology and the socio-political vicissitudes Russia went through during the early days of colour photography. Not only am i no expert in Russian history nor photography techniques but i’m also an ultra lazy blogger. I hope you will excuse me if i just sum up (but mostly cut/copy/paste) Sviblova’s words below:

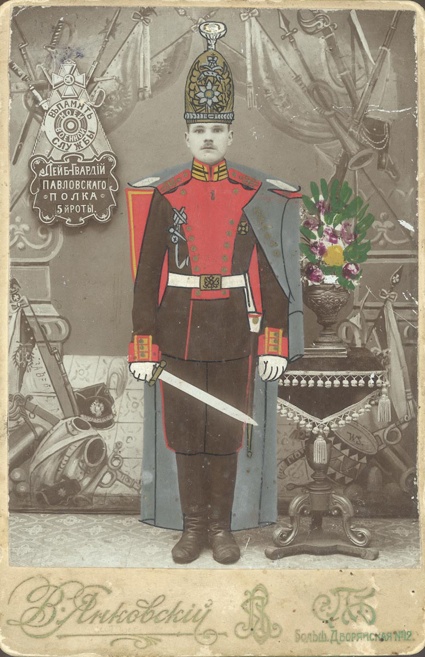

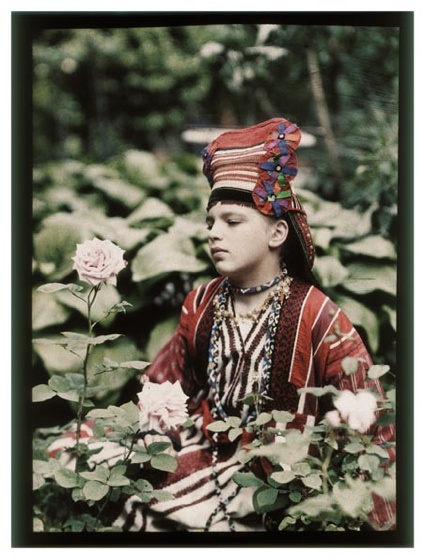

Colour became widespread in Russian photography in the 1860s. At the time, colour was added to photographic prints manually using watercolour and oil paints. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries Russia was undergoing two opposing trends: active europeanisation and search for a national identity that translated into tinted photographs that portrayed people wearing national costumes — Russian, Tatar, Caucasian, Ukrainian, etc.

V. Yankovsky “In memory of my military service”. Saint Petersburg. Beginning of 1910s Collodion, painting Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Moscow House of Photography Museum

V. Yankovsky “In memory of my military service”. Saint Petersburg. Beginning of 1910s Collodion, painting Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Moscow House of Photography Museum

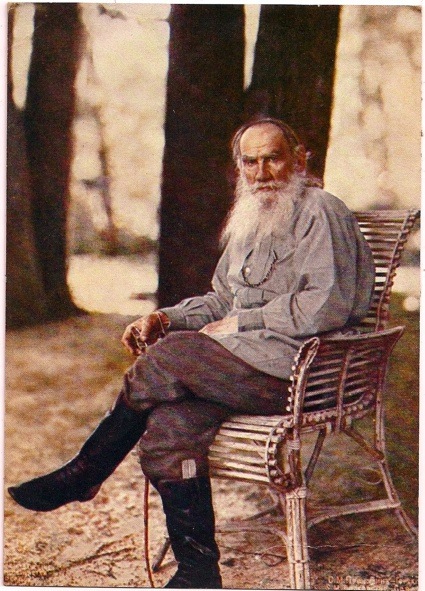

The photographic documentation of life in the Russian Empire in the early 20th century acquired the status of a State objective. In May 1909 Tsar Nicholas II gave an audience to the photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky who, in 1902, had announced a technique for creating colour photographs by combining shots taken successively through light filters coloured blue, green and red. Delighted with this invention, Emperor Nicholas II commissioned the photographer to take colour photographs of life in the various regions of the Empire.

Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, Portrait of Lev Tolstoy, 25 May 1908

Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, Portrait of Lev Tolstoy, 25 May 1908

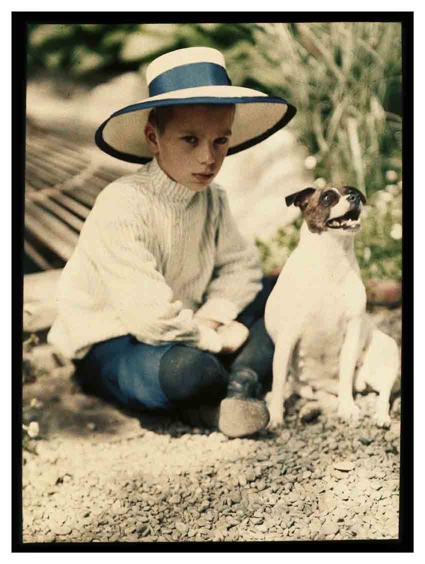

Meanwhile autochrome pictures by the Lumière brothers, with whom Prokudin-Gorsky worked after emigrating to France, became very popular in early 20th-century Russia. Autochromes, colour transparencies on a glass backing, could be viewed against the light, or projected with the aid of special apparatus. They were used by Pyotr Vedenisov, a nobleman whose hobby was to photograph his own family life. The private image later provided an excellent description of the typical lifestyle enjoyed at the time by educated Russian noblemen.

Piotr Vedenisov, Kolya Kozakov and the Dog Gipsy. Yalta. 1910-1911 Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Piotr Vedenisov, Kolya Kozakov and the Dog Gipsy. Yalta. 1910-1911 Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Piotr Vedenisov, Vera Kozakov in Folk Dress. 1914, Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Piotr Vedenisov, Vera Kozakov in Folk Dress. 1914, Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Piotr Vedenisov. Tania, Natasha, Kolia and Liza Kozakov, Vera Nikolayevna Vedenisov and Elena Frantsevna Bazilev. Yalta, 1910-1911

Piotr Vedenisov. Tania, Natasha, Kolia and Liza Kozakov, Vera Nikolayevna Vedenisov and Elena Frantsevna Bazilev. Yalta, 1910-1911

The onset of the First World War in 1914 and October Revolution in 1917 reduced to ruins the Russia whose memory is preserved in the tinted photographs and autochromes of the late 19th to early 20th centuries. Vladimir Lenin and the new Soviet government saw photography as an important propaganda weapon for a country where 70% of the population were unable to read or write. From the mid-1920s photomontage, used as an ideological ‘visual weapon’, was widespread in the Soviet Union, enthusiastically encouraged by the Bolsheviks.

From the mid-1920s Alexander Rodchenko regenerated the forgotten technique of hand colouring his own photographs. In 1937, at the height of Stalin’s repression, Rodchenko began photographing classical ballet and opera, using the arsenal of his aesthetic opponents, the Russian pictorialists, who by that time were subject to harsh repression. For Alexander Rodchenko soft focus, classical subject matter and toning typical of pictorial photography were a mediated way of expressing his internal escapism and tragic disillusionment with the Soviet utopia.

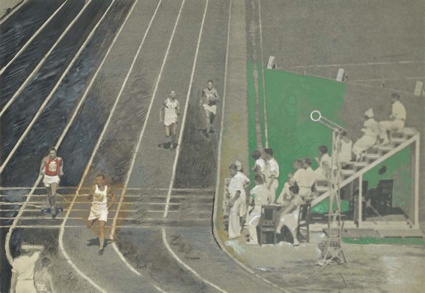

Alexander Rodchenko. Race. “Dynamo” Stadium. 1935. Artist’s gelatine silver print, gouache. Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow/ Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Race. “Dynamo” Stadium. 1935. Artist’s gelatine silver print, gouache. Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow/ Moscow House of Photography Museum

Varvara Stepanova, Red Army Men, photomontage for “Abroad” magazine, 1930 collection B Ignatovich

Varvara Stepanova, Red Army Men, photomontage for “Abroad” magazine, 1930 collection B Ignatovich

In 1932 general rules for socialist realism were published in the USSR, as the only creative method for all forms of art, including photographic. Soviet art had to reflect Soviet myths about the happiest people in the happiest country, not real life and real people.

In 1936 both Agfa and Kodak introduced colour film but Second World War delayed their broad distribution to the amateur photography market. In the USSR colour photography only appeared at the end of the war.

Until the mid-1970s, in the USSR negative film for printing colour photographs was a luxury only available to a few official photographers who worked for major Soviet publications. All of them were obliged to follow the canons of socialist realism and practise staged reportage.

Yakov Khalip. Sea cadets. End of 1940s. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Yakov Khalip. Sea cadets. End of 1940s. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

From the late 1950s, in the Khrushchev Thaw after the debunking of Stalin’s cult of personality, the canons of socialist realism softened and permitted a certain freedom in aesthetics, allowing photography to move closer to reality.

In the postwar period, during the 1950s to 1960s life gradually improved and coloured souvenir photo portraits again appeared on the mass market. They were usually produced by unknown and ‘unofficial’ photographers, since private photo studios that used to carry out such commissions were now forbidden, and the State exercised a total monopoly on photography by the 1930s.

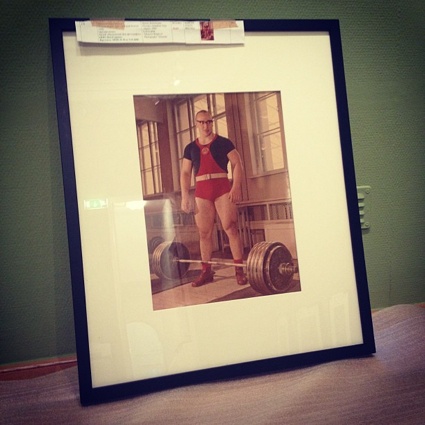

Dmitry Baltermants, Portrait of Olympic champion Yury Vlasov, 1960. Installation shot by Foam

Dmitry Baltermants, Portrait of Olympic champion Yury Vlasov, 1960. Installation shot by Foam

Dmitry Baltermants Show-window. Beginning of 1970s Colour print Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Dmitry Baltermants Archive © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Dmitry Baltermants Show-window. Beginning of 1970s Colour print Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Dmitry Baltermants Archive © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Dmitry Baltermants Meeting in the tundra. From the “Meetings with Chukotka” series. 1972 Colour print Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Dmitry Baltermants Archive © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Dmitry Baltermants Meeting in the tundra. From the “Meetings with Chukotka” series. 1972 Colour print Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Dmitry Baltermants Archive © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Dmitri Baltermants, Rain, 1960s

Dmitri Baltermants, Rain, 1960s

Dmitry Baltermants. Moscow. 1960s. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

Dmitry Baltermants. Moscow. 1960s. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

Robert Diament. He has turned her head. Beginning of 1960s. Colour print. Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow/ Moscow House of Photography Museum

Robert Diament. He has turned her head. Beginning of 1960s. Colour print. Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow/ Moscow House of Photography Museum

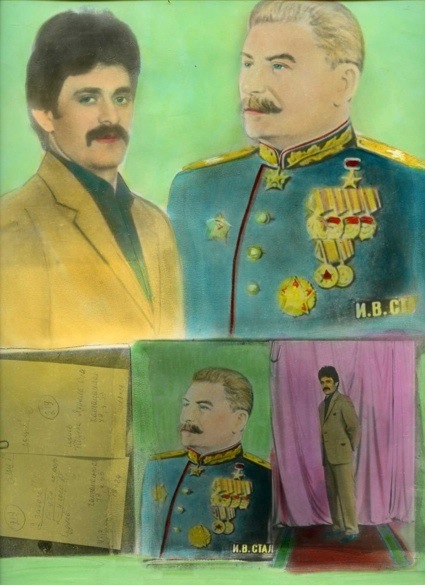

Boris Mikhailov copied, enlarged and tinted these kitsch photo souvenirs to supplement his income at his photo lab in the early 1970s. Revealing and deconstructing the nature of Soviet myths in the process.

Boris Mikhailov, From the series Luriki, end of 1970s – beginning of 1980s

Boris Mikhailov, From the series Luriki, end of 1970s – beginning of 1980s

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled (from the series Luriki), 1971-1985

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled (from the series Luriki), 1971-1985

Colour transparency film, which could be developed even in domestic surroundings, appeared on the Soviet mass market in the 1960s and 1970s. It was widely used by amateurs, who created transparencies that could be viewed at home with a slide projector. An unofficial art form emerging in the USSR at this time developed the aesthetics and means for a new artistic conceptualisation of reality, quite different from the socialist realism that still prevailed, although somewhat modified.

More than half a century of Soviet power after the 1917 Revolution radically altered Russia. The photographer was certainly not required or even allowed to take nude studies as corporeality and sexuality were seen as inherent signs of an independent individual. In photographing Suzi Et Cetera Boris Mikhailov disrupts the norms and reveals characters, his own and that of his subjects. It was impossible to show these shots in public, but slides could be projected at home, in the workshops of his artist friends or the often semi-underground clubs of the scientific and technical intelligentsia, who began to revive during Khrushchev’s Thaw after the Stalinist repression. Boris Mikhailov’s slide projections are now analogous to the apartment exhibitions of unofficial art. By means of colour he displayed the dismal standardisation and squalor of surrounding life, and his slide performances helped to unite people whose consciousness and life in those years began to escape from the dogmatic network of Soviet ideology, which permitted only one colour — red.

Photo of the exhibition opening © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

Photo of the exhibition opening © Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

More photos in Le Journal de la Photographie and Multimedia Art Museum Moscow.

Primrose – Russian Colour Photography is at Foam in Amsterdam until 3 April 2013.

Related posts: Soviet Photomontages 1917-1953 and

Russian Criminal Tattoo portraits.