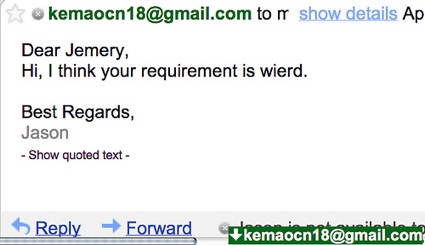

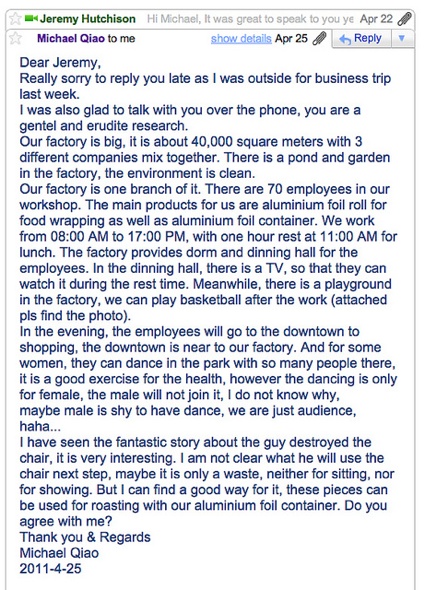

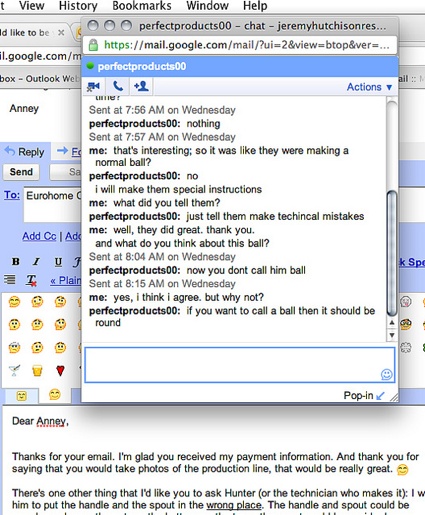

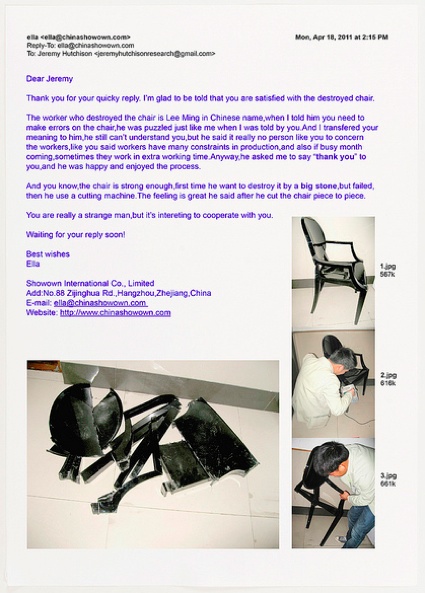

Earlier this year, Jeremy Hutchison sent emails to manufacturers around the world, asking them to produce a fairly simple and common item. He added a special requirement though: the product had to be imperfect, come with an intentional error. Moreover, the worker was in charge of deciding which kind of error, malfunction or fault he would add to the good. The artist reassured the factory that, whatever the result, he would pay for the faulty object.

Incorrectly manufactured Philippe Starck Louis Ghost Chair, made by Lee Ming, Showown International Co.,Limited, Zhejiang, China

Incorrectly manufactured Philippe Starck Louis Ghost Chair, made by Lee Ming, Showown International Co.,Limited, Zhejiang, China

The outcome of the experiment is fascinating. Sometimes, the object was shipped in bits and pieces because the worker decided they would simply damage it after fabrication. Most of the time, however, the dysfunctioning good demonstrates the creativity and imagination of men doing repetitive gestures day after day in the factory: a comb without its teeth, a walking stick turned into a nunchaku, a football ball that is anything but round, a pair of sunglasses without the space for the nose, etc. The objects are amusing but they also give their makers/designers a presence and identity we would otherwise not think of giving them.

Untitled (made by Carlos Barrachina, Segorbina de Bastones, Segorbe, Spain)

Untitled (made by Carlos Barrachina, Segorbina de Bastones, Segorbe, Spain)

Untitled, (factory shot, Segorbina de Bastones, Segorbe, Spain)

Untitled, (factory shot, Segorbina de Bastones, Segorbe, Spain)

‘Lame Landships’ (designed and titled by Kim at Hui-Yo Sports, Guangdong, China)

‘Lame Landships’ (designed and titled by Kim at Hui-Yo Sports, Guangdong, China)

“[Err is] about creating deliberate miscommunication,” Hutchison told Creative Review, “forging a moment of poetry within a hyper-efficient system of digital exchange. It’s about an invisible global workforce, and their connection to the relentless regurgitation of stuff. It’s about Duchamp and the readymade, but updated to exist within the context of today’s globalised economy. It’s about the rub between art and design, the mass-produced and unique, the functional and the dysfunctional.”

Hutchison kept track of all the email exchanges, all the skype conversations he had with the people working in the factories. At first, the answers he got expressed bafflement and perplexity.

Soon enough though, some kind of conversation emerged…

Jeremy’s project toured the blogs and design/art magazines but i finally got to see it in detail a month ago, when i visited New Sensations, a competition and exhibition organized by the Saatchi Gallery and Channel 4 to highlight works made by some of the most talented students graduating from universities and colleges across the UK and Republic of Ireland.

No matter how much i had read and seen about his project, i still wanted to interview Jeremy. Here we go:

Hi Jeremy! One of the most charming parts of the Err project is the exchange of emails and instant messaging conversations you had with employees of the manufacturing companies. I noticed that at some point, they would inform you about the working conditions of the workers. How did these details about TVs in the dinner rooms, women dancing in the park and meal times arise? Was it a question you asked or did the information come spontaneously? Do you feel that they emerged as a kind of self-defense against the assumptions we might have in ‘the West’ that the workers are treated poorly or are they the result of some personal relationship you managed to created over the exchange of emails?

Well, I set out to develop a personal relationship to the people who make things. Something beyond ‘producers’ and ‘consumers’. I wanted to disrupt a relationship based on a capitalist exchange, where communication operates within strict linguistic codes: price, quantity, customs port. I wanted to introduce a different register into these conversations, to ask what they watched on telly, what music they danced to, what they thought about while they worked.

Obviously this information didn’t come spontaneously! But everyone’s curious about everyone else. So as our conversations lost their economic anchor and drifted into strange territory, a kind of unspoken permission was given. We talked about Indian cigarettes, Shanghai dragon-boat racing, the Colombian drugs trade. In exchange for pictures of my newborn son, they sent me images of factory dormitories, production lines, workers’ canteens. Sometimes they wanted to dispel my Western perceptions. Sometimes they simply wanted something else to talk about. Either way, we exchanged a lot of trust, curiosity, and emoticons.

Lie Liu (factory worker), Tianjin Jessy Musical Instrument Co, Tianjin, China

Lie Liu (factory worker), Tianjin Jessy Musical Instrument Co, Tianjin, China

Mr Azam, Racing Wear, Sialkot Pakistan

Mr Azam, Racing Wear, Sialkot Pakistan

Xianning Chang Rong Sport Products Co., Ltd

Xianning Chang Rong Sport Products Co., Ltd

Basketball court, foil container factory, Zhangjiagang Xiongda, Jiangsu, China

Basketball court, foil container factory, Zhangjiagang Xiongda, Jiangsu, China

Were you expecting to struggle so much to get your request understood? The football ball that looks like a football ball but isn’t one seems to have caused a lot of trouble for example. Can you also explain us what happened with the ball?

To be honest, I didn’t expect a single response. My request was absurd: factories normally take orders of five thousand – not one. And certainly not one with an error. So I guess it came down to finding people who were willing to engage with the absurd, who wanted to know what would happen.

I found a factory in Pakistan that makes 100,000 footballs a month. I made friends with the Sales Director, Waleed. He agreed to make an incorrect football, but without his boss knowing. Every person in the production line made an error: the patches were in the wrong places, the stitching was terrible, the bladder poured out. It was lovely.

But ironically, the error went further. I got a frantic call in the middle of the night: Waleed was at the customs port. The authorities had seized the ball. When he explained than an Englishman had ordered a ball with errors, all hell broke loose. They said it was illegal to fabricate incorrect products, and they would revoke his company’s trading licence. I explained that this product wasn’t incorrect since it was exactly what I’d ordered. Days passed: nothing. Lost in the bureaucracy of Pakistani customs, I eventually got through to the high commissioner in Islamabad.

She was very apologetic, and explained that 20kg of heroin had recently passed under the radar at Sialkot customs. So everyone was feeling a bit paranoid. She issued a document stating that “the sculpture/artwork looks like a football but in fact is not a football and primarily this object is not for using as a football but is an artwork.” But it was too late: someone had destroyed the ball, and it disappeared without a trace. I never quite found out who.

But Waleed and I are still friends.

Untitled (made at TataPak, Sialkot Pakistan)

Untitled (made at TataPak, Sialkot Pakistan)

TataPak, Sialkot Pakistan

TataPak, Sialkot Pakistan

I was also interested in hearing more about the meaning and narrative that some of the employees injected into the final artifact. For example, the comb that you cannot use to comb even got a name and a whole text justifying its use to ‘a completely different section of society its unique something out of this world.’

I was also interested in hearing more about the meaning and narrative that some of the employees injected into the final artifact. For example, the comb that you cannot use to comb even got a name and a whole text justifying its use to ‘a completely different section of society its unique something out of this world.’

Well, the comb was made in a small factory in Kolkata. My contact Manoj explained what happened when he relayed my request: ‘everyone thought I have gone mad or mis-read your enquiry as everyone in the world strives to improve not to create error.’ It seemed like the entire factory was involved in my dysfunctional comb. “We have named it IMPICO because first it was impossible to make and then when we eventually made it, it was impossible to use. So Impossible Comb = IMPICO.” Manoj was curious about the market: How would I sell it? Who would buy it? I said I wasn’t sure. So I suggested we make a print ad. He wrote the copy, and I did the art direction.

One of Marx’s major quarrels with capitalism was the alien relationship it creates between the worker and the product of his work. I’d been wondering about this relationship, and how it might be altered: What if we lived in a world where the factory worker claimed authorship over his creation? What if narrative was injected into the object? How would this affect it?

Perhaps the intellectual activity they were required to perform caused a momentary jolt in their position, inviting them to insert meaning, humour, personality into their work. I think they enjoyed it. Apparently the man who chainsawed the acrylic chair to bits found it rather cathartic: ‘The feeling was great after he cut the chair piece to piece… he was happy and enjoyed the process’. He told his boss to thank me, so that was nice.

Impico (Made by Mr Kartick, Mr Ram, Mr Vikash, Star Creations, Kolkata, India)

Impico (Made by Mr Kartick, Mr Ram, Mr Vikash, Star Creations, Kolkata, India)

Manoj Choudhary, manager of Star Creations comb factory, Kolkata, India

Manoj Choudhary, manager of Star Creations comb factory, Kolkata, India

Err celebrates the creativity of the factory workers that hardly ever gets the opportunity to emerge. It is full of humor and poetry but could you tell us about the maybe ‘darker’ motivation behind the project if there’s any? Did you conceive Err as a critical comment on capitalism, on the anonymous and often underpaid workforce who works tirelessly to provide Europeans with objects they can afford?

I don’t think it’s my job to take a moral stance on things – more to ask energetic questions. So rather than reinforce pre-existing arguments (e.g. capitalism / anti-capitalism), I wanted to see what would happen if you lodged nonsense into the mechanics of a hyper-efficient global machine. To manufacture error.

But this project didn’t come out of nowhere. It was triggered by an article I read about the Apple Mac factory in Shenzhen. Consumer hunger for iPads had reached such dizzying heights that life on the Chinese assembly line had become pretty devastating. The management had attached nets around the building, to catch people who were throwing themselves off the roof. One worker told the newspaper that ‘he would deliberately drop something on the ground so that he could have a few seconds of rest when picking it up.’

An intentional error is a strange idea – illogical, oxymoronic. And fundamentally human. So in some ways, Err is simply a continuation of this worker’s gesture. It’s a moment of respite from the endless repetition of the global production line.

Err is a tremendously successful work. It has been exhibited in various venues and was discussed in countless blogs and magazine articles. Are you tempted to come up with a project that somehow continues or Err in the future or explores other sides of goods manufacturing?

Err is a tremendously successful work. It has been exhibited in various venues and was discussed in countless blogs and magazine articles. Are you tempted to come up with a project that somehow continues or Err in the future or explores other sides of goods manufacturing?

Well the simple answer is that Err isn’t finished. Next year, the confusion that this project performed in mass-production will belch out as a luxury brand. It’ll look like something you know, but somehow everything will be wrong: a marketing platform sabotaged by its own miscommunication.

I want my work to deal with what’s out there: mass production, emerging markets, Skype, consumerism, economic meltdown. So I’ve found manufacturing a useful vehicle to engage with the chaos of the 21st Century. While I want to avoid formula at all costs, I do have a couple more projects that operate in a similar realm. One of these will launch at Paradise Row gallery, and another might materialise this summer as an outdoor sculpture for the Southbank Centre, London.

The Road from Ramallah to Jerusalem, 2010

The Road from Ramallah to Jerusalem, 2010

Finally i was intrigued by the bitter-sweet projects you developed in Palestine and Israel. You seem to have adopted the role of the unlucky and innocent British tourist who puzzles Israeli with labels written in arabic and cycles against separation walls. Is it possible not to take a stand and judge when working in Israel and Palestine and exploring the political and social situation? Were the situation and relationships between people different from what you had expected from what the press tells us?

My experience in Palestine / Israel was transformative. I found two sides shouting different languages over an 8 metre high wall. People crawling through sewage tunnels to see their families. Semites making anti-semitic slurs against other semites. Nothing made sense. So what does a white middle-class English boy do in a conflict zone? He rides into concrete walls, drives around roundabouts, buys milk from shops that aren’t selling it. Somewhere in the noise and confusion, I realised a few things. That it’s essential to remain impartial – but impossible to do so. That confusion may be more productive than resolution. That things aren’t supposed to make sense.

The press offer us reports of progress in the Middle East. They promote a narrative that edges towards ultimate resolution. And it’s their duty to do so: we are addicted to a Christian / Humanist rhetoric of salvation. But the complexity of the Middle East doesn’t seem to fit into tidy dialectics. After all, we must – at the very least – be prepared to listen to the other side to form an antithesis. And I didn’t meet a single person that wanted to do that.

So while it’s important to stand by something, to have an opinion, I think its more important to offer an alternative. Because whatever beliefs I hold true, I’d like to hold them lightly, flip them over, even toss them into the wind.

Thanks Jeremy!

All images courtesy of Jeremy Hutchison.