Photo by Nick Ballon

Photo by Nick Ballon

Interaction designer Nelly Ben Hayoun (whose works, Super K Sonic Booooum and The Soyuz Chair, you might remember) and geography researcher Dr Alison J Williams teamed up for Airspace Activism, a project that investigates the geographies of UK military airspaces which are used by air forces to train and prepare for combat situations.

One of the outcomes of Nelly and Alison’s collaboration is the Theatre of the Air. A video using interviews with military pilots and navigators to understand how they perceive the geometries of the spaces through which they fly.

These airspaces exist in 3D volumes of space that can be activated and deactivated at different times. However, aviators only have two-dimensional air charts to ‘see’ these spaces, so they have to translate these mappings into three dimensions in their minds in order to be able to safely fly through them.

In order to make these invisible airspaces visible, Nelly and Dr. Williams worked on another project which will be the focus of this post. It’s a 4 meters high windfarm that civilians could use to create radar white noise and prevent aircraft flying overhead, therefore reclaiming their piece of sky. An “audio-locator” –which a size is far more manageable that the acoustic locators used during the war before the invention of radar– warns the user of any incoming aircraft and so that he or she has time to set the wind farm in motion.

The wind mill was exhibited this week in London and will be up again in another exhibition, in Newcastle this time, from 28th June until 7th July.

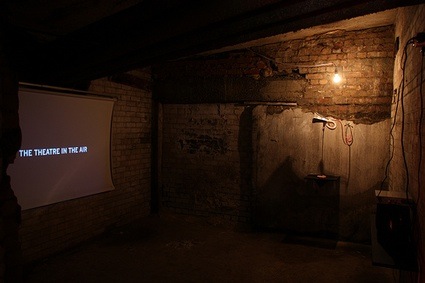

Inside the WWII bunker. Photo by Nicolas Myers

Inside the WWII bunker. Photo by Nicolas Myers

Can you tell me something about the location of your pieces? One is in London and the other in Newcastle? The London one doesn’t seem to be a typical white space gallery though. Who chose the locations and why?

Nelly: A few words about the project itself, which I think will make sense with the location where it is presented in a disused WWII air raid shelter in Dalston for London and in an art space at the Exlibris Gallery, Newcastle University, in Newcastle.

This project seeks to make the invisible airspace visible. It achieves this through the construction of a vertical object that empowers us to take back control of these spaces reserved for military purposes.

During the early years of aviation aircraft flew at a relatively low altitude. However, laws existed that gave land-owners ownership of the entirety of the vertical space above the footprint of their house, including the air. This led to a myriad of problems for aviators and landowners who became locked in battle over payment for access to these spaces.

More recently, wind farms have become a contentious issue. Environmentalists either protest their building in areas of natural beauty, or cry out for their erection to reduce our dependence of fossil fuels and nuclear power. The military dislikes wind farms because they create no fly-zones in the sky, because of their production of radar white noise, which prevents aircraft flying over them.

This project synthesises these ideas, proposing an activism approach the focuses upon the idea of being able to generate and enact your own airspace though the deployment of a personalised wind farm. This creates a form of mechanical imperialism, through enabling control of an individual airspace.

A two-horn system of acoustic location at Bolling Field, USA, in 1921

A two-horn system of acoustic location at Bolling Field, USA, in 1921

The project is composed of a wind farm to use on your rooftop, and an audio locator that amplifies the sound of an aircraft engine. This enables the wind farm owner to hear an aircraft at distance and erect the wind farm in time to prevent the aircraft flying overhead.

Audio Locator. Photo by Nick Ballon

Audio Locator. Photo by Nick Ballon

A few weeks ago, while I was already working with Dr Alison J Williams on completing the design pieces for the Interventions exhibition in the The Exlibris Gallery in Newcastle, I was contacted by Space In Between, an arts-based collective operating in London. Space In Between was created in 2009 by the three young and very dynamic curators/artists Hannah Hooks, Laura MacFarlane and Ida Champion, who enjoy challenging emerging artists and designers by asking them to exhibit in unusual spaces such as this WWII air raid shelter bunker. This was really an opportunity not to be missed! Spaces such as this one really bring sense to the work and inform it as well with history and context.

It seems to me, that design is more than simply objects and should be embedded in an experience, something that will last in your memory like when you see a painting and you remember the tone of it. Those kinds of exhibition spaces really help to achieve that. They are performative by themselves, and prepare the audience to get into the experiences.

The pieces are now on their way to Newcastle University as part of the Interventions project, a project set by Joe Malia and Dr. Mónica Moreno Figueroa at Newcastle University’s Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. This project and exhibition pairs 6 designers with 6 social scientists from Newcastle University to come up with provocative, speculative and creative overlap between social and cultural research and design.

Inside the WWII bunker. Photo by Nicolas Myers

Inside the WWII bunker. Photo by Nicolas Myers

How did you come to collaborate with Dr Alison J Williams?

Nelly: We met though the Interventions project, over 8 weeks, we began our collaboration by Alison sharing her research with me, sending her written work and transcripts of interviews with military pilots and navigators. From this I identified several key elements that could inspire a design proposal. We discussed them and over the course of two days developed ideas to take forward.

I was really lucky in meeting Alison through this project, her research stimulated my existing interest in airspace and in designing for the invisible. I was fascinated by the vocabulary she uses and how imaginative it can be. She talks about how ‘ The aircraft ENACTS the air’ , developing its own performance. How the aircraft is an ‘assemblage’, she explains about those ‘hidden geographies’ those ‘ vertical geopolitics’ , how pilots ‘ book’ their piece of air, what does ‘flying in theater’ means, ‘volumes of airspace’, the ‘aerial sovereignty’ of the aircraft… the airspace with Alison is a ‘lived spatiality’, ‘a craft network’. So, yes, you can imagine my excitement when reading and meeting her in Newcastle!

Photo by Nick Ballon

Photo by Nick Ballon

Do these geographies of military airspaces have any impact on the life of ordinary people like us? Could my ryanair flight from Turin to Brussels pass through them? Are they located above cities for example?

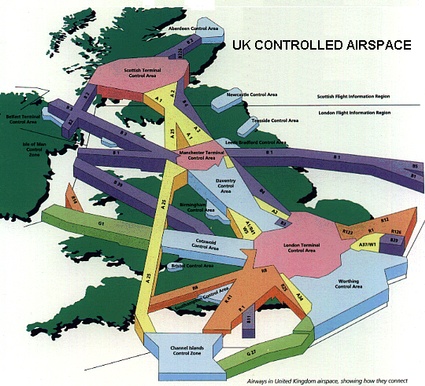

Dr Alison J Williams: The geographies of UK military airspaces do have an impact on the general public in many ways, through low flying and through flying though airspaces that other airspace users also want to use. This only really affects the private pilot community however. UK airspace is segregated so there are civil airspaces which commercial aircraft use to travel from airport A to airport B. These are like aerial motorways that link airports, and are usually known as air lanes. There are other airspaces that are used by both private pilots and the military. These are found in rural areas of the UK, in Wales, North Yorkshire, East Anglia, North Scotland, Northern England, Cornwall. You can get more detailed information on these spaces from the website of the Civil Aviation Authority. All this information is in the public domain. The military trains in these spaces. In some of these areas segregated airspaces exist. These are usually called danger areas and are where the military can train but private pilots and commercial aircraft are not allowed to enter without authorisation. These are usually over military ranges or training facilities.

Your flight from Turin to Brussels would not be affected by UK military airspace as you wouldn’t be flying through UK airspace. In any case UK airspace operates a system that keeps civil, private, and military aircraft separated. Civil aircraft would not fly through UK military airspace that is being used.

Nelly: The airspace is such a complex, regimented space. It’s made of corridors of different heights. Each force has some piece of air reserved that they book for the day. Military aircraft are guided with different frequencies than touristic aircraft.

All of this is controlled so nobody crashes into each other. Somehow the visualization I have of it is like a swan lake choreography!

They don’t have a clear impact on our daily life, except if you are a pilot, we all have a passive access to these airspaces, which I think is really unfair! We aren’t able to perform in it. My practice is a lot about giving access to amateurs to expert domains. That’s really what is the project about, making this invisible, inaccessible air Active to us, making it real and physical in our daily life.

Nelly Ben Hayoun, The theater in the Air

I’m sure my question will seem very naive but why is ‘radar white noise’ a problem for these planes?

Nelly: When you are ‘flying’ a plane you received radio signal from radar to tell you your strict position that stop you from messing up with others people’s pieces of air ( usually military forces such as navy) and give you an indication on your height in the air. When windfarm create those microwave radiation they stop radars (positioned usually on earth) to deliver those data, they create white noise in their radar which become then NO_FLIGHT zone for the pilots.

Alison: Radar white noise is a problem because it in essence blinds the radar in the aircraft, so the pilot can’t use their radar to see what is around them. Wind farms generate white noise because they are large metal structures and as such military aircraft don’t fly over them because it disrupts their radar systems.

Do you expect some retaliation for the UK military for the way that your windmill interact with their spaces?

Alison: This project, although based on research on military airspace, is not only about military airspace. The idea is to show how we can exert control over the airspace above our heads and through this prevent aircraft flying through it. It’s not about targeting military aircraft flights. Military airspaces aren’t above cities so the windmill would not be directly targeting military airspaces if it were placed in a suburban garden. Given these parameters I see no reason why the UK military would have any issue with the work.

Nelly: That will be very interesting. And ultimately the aim of the project, what will happen next? Will this DIY wild wind farms become the new target on military aircrafts?! No, but seriously, I do think that design must be engaged, It’s ‘Revolution time’ for designers to assume their creative responsibilities, what is the point of putting another thing out there if there is no message? That can be poetic, aesthetic, functional, provocative, emotional, performance based… In any case, I will be there, reclaiming my piece of sky, waiting on the top of my pink windmill for a wild military aircraft to pass by!

Thanks Nelly and Dr. Williams!

Where beats this Human Heart/ Space in Between. Exhibition ran 19/06/10 ‐ 23/06/10. The Bunker @ The Print House, 18 Ashwin street, London E8 3DL.

and

Interventions Project / Newcastle University. Group show with Michiko Nitta, Grit Hartung, Dane Whitehurst Joe Malia, Robert Phillips, Ben Singleton, Stuart Munro

Exhibition runs 28th June-7th July at The Exlibris Gallery, The Quadrangle, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne.