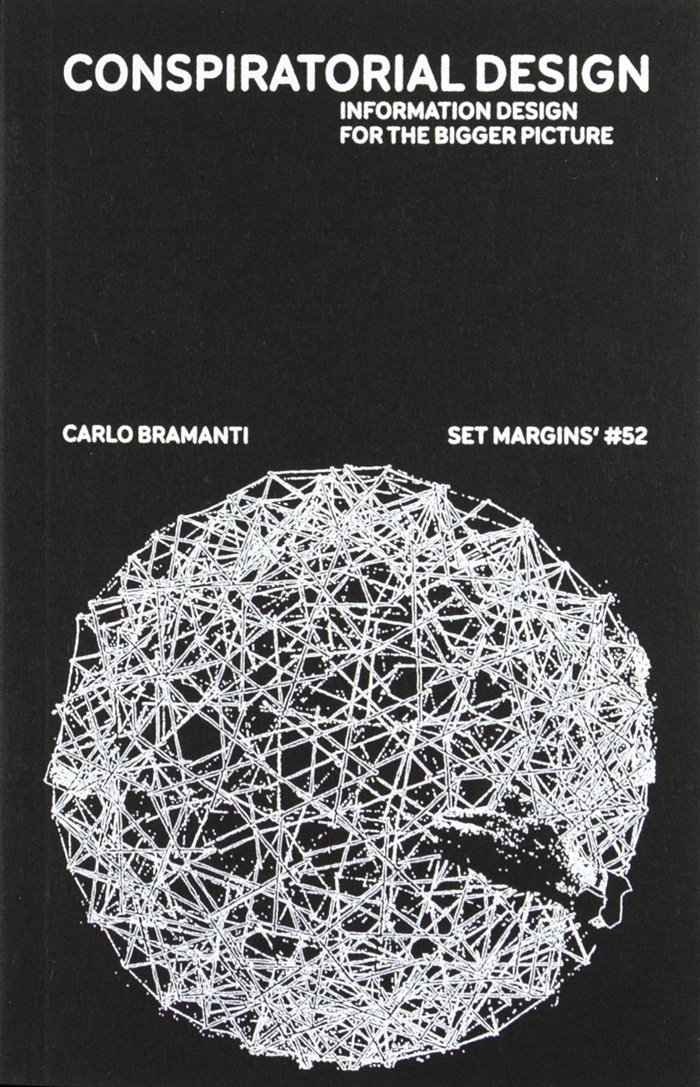

Conspiratorial Design. Information design for the bigger picture, by Carlo Bramanti. Afterwords by Silvio Lorusso.

Bringing two concepts we usually regard as antithetical, visual designer Carlo Bramanti examines how design and conspiracy theory intersect in their practices and output. Design is generally perceived as a discipline that makes the complex intelligible; it illustrates reliable facts and streamlines information. Conspiracy theories, on the other hand, stretch facts to their most grotesque limits; they create chaos and confusion. And yet, for Bramanti, both attempt to address the same human aspiration for meaning and order.

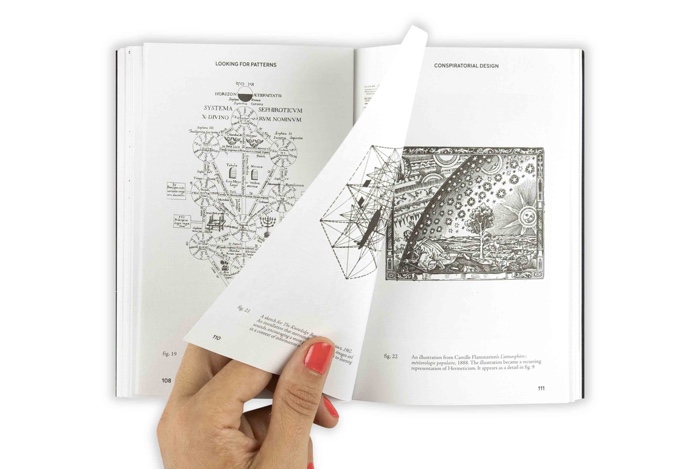

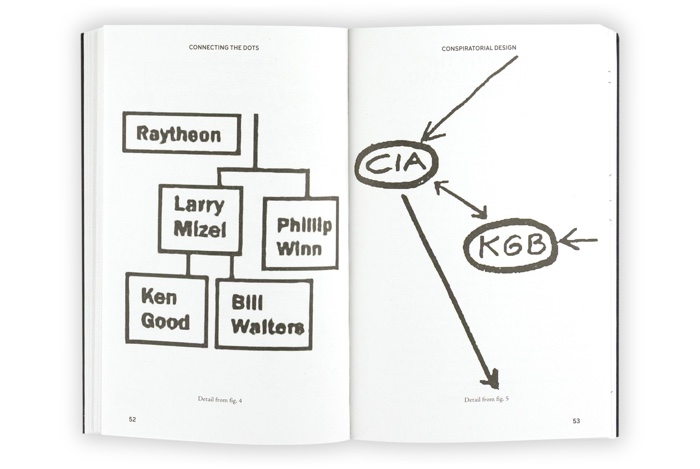

Design (in particular information design) and conspiracy theory, he says, share a tendency to think in terms of large-scale systems. They both look for strong and seductive narratives that will reveal “the bigger picture”. Designers process vast amounts of information and synthesise them in an engaging way. To do so, they look for patterns and new connections, which makes them vulnerable to conspiracy. But while design strives to “raise awareness”, conspiracy theory talks about “awakening”.

Bramanti finds the connections between design and conspiracy theory so compelling that he coined a term for the common ground that they share: Conspiratorial Design.

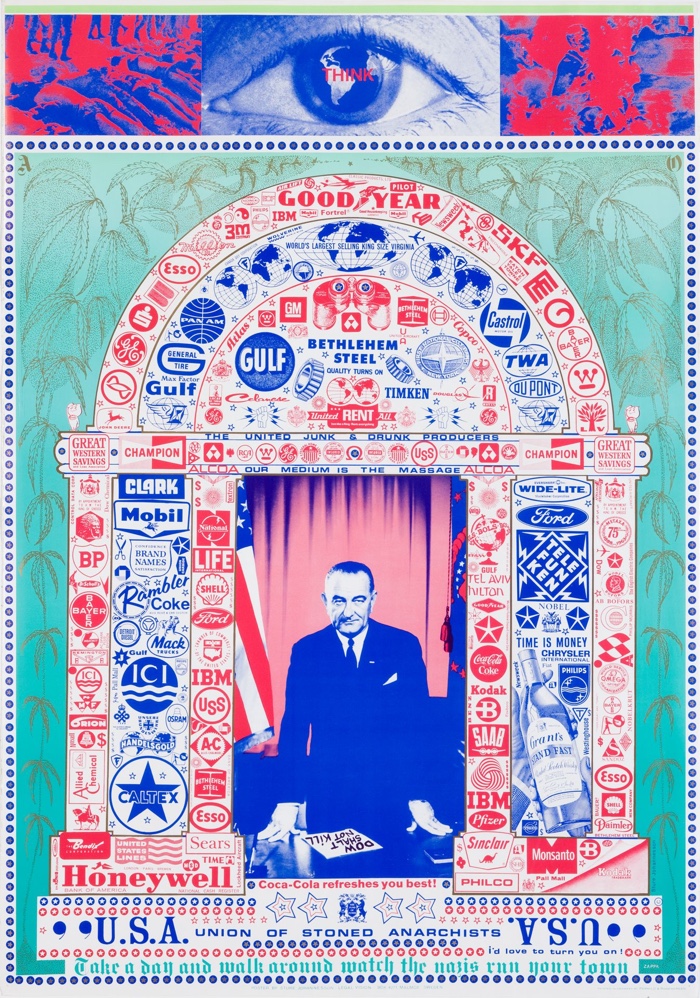

Sture Johannesson, Dow Shalt Not Kill! U.S.A. – Union of Stoned Anarchists, 1967

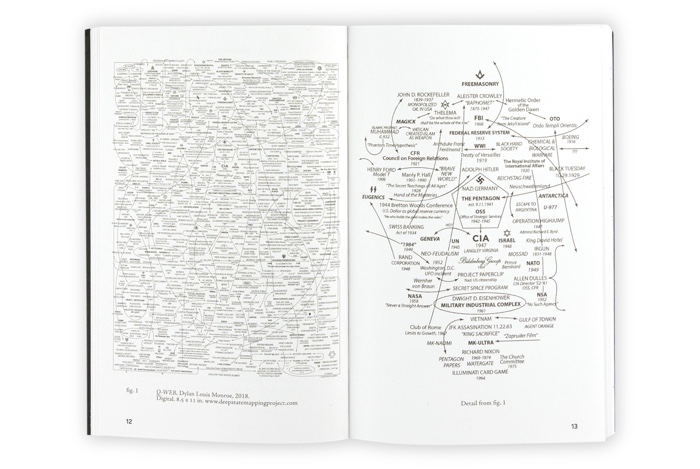

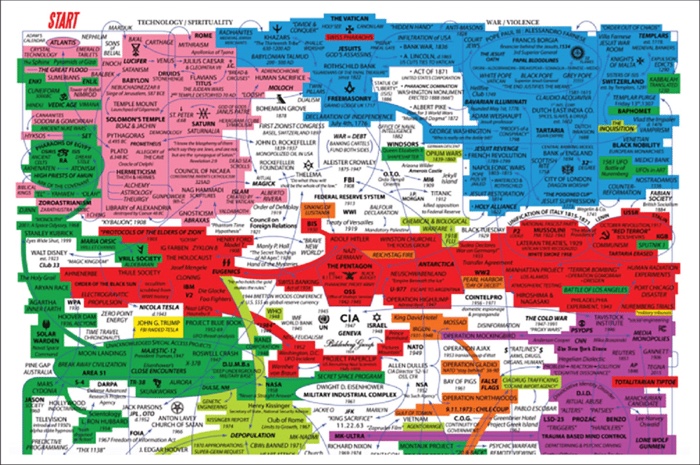

Dylan Louis Monroe, The Q Web or Deep State Mapping Project, 2018

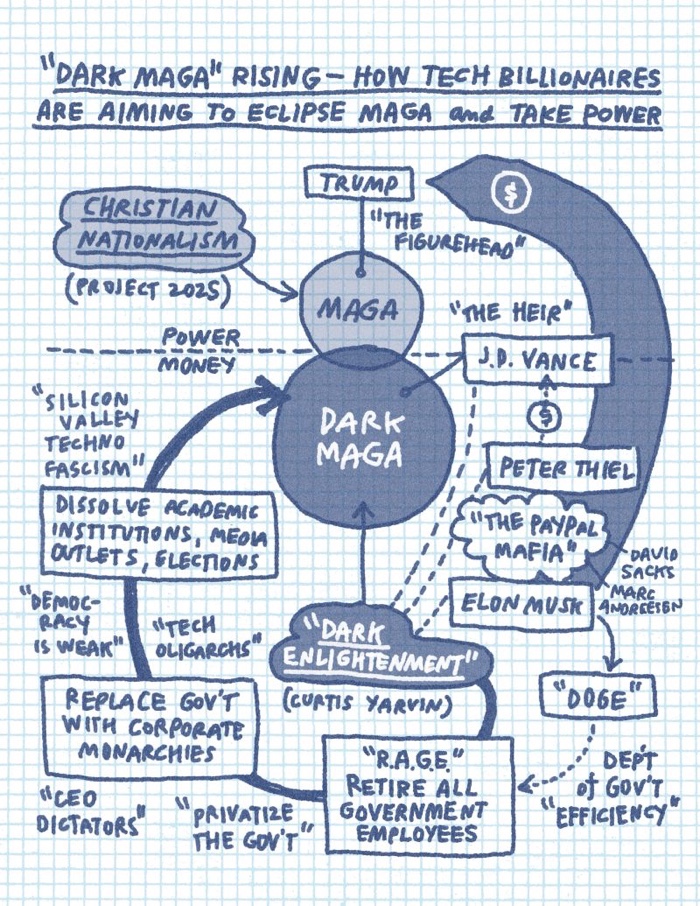

Conspiracy Design is characterised by a desire (or rather an illusion) of control over uncontrollable amounts of information, a reliance on the community and its acceptance of a certain degree of fiction and parody. Parody allows for a level of ambiguity regarding how much we truly believe in the narratives, and it’s precisely the community that keeps together the suspension of belief. Bramanti compares the phenomenon to kayfabe, the portrayal of staged events or storylines as genuine in pro wrestling. This suspension of belief involves the performers, the audience and the organisers of the wrestling events. It’s easy to see how kayfabe translates into conspiracy theory where degrees of belief vary to the point that truthfulness becomes insignificant. For Bramanti, certain forms of design that like to recreate the sensation of research and criticality also engage with kayfable, the conclusions in the case of design become irrelevant as long as “awareness” is raised.

Craighton Berman, Dark MAGA, 2025

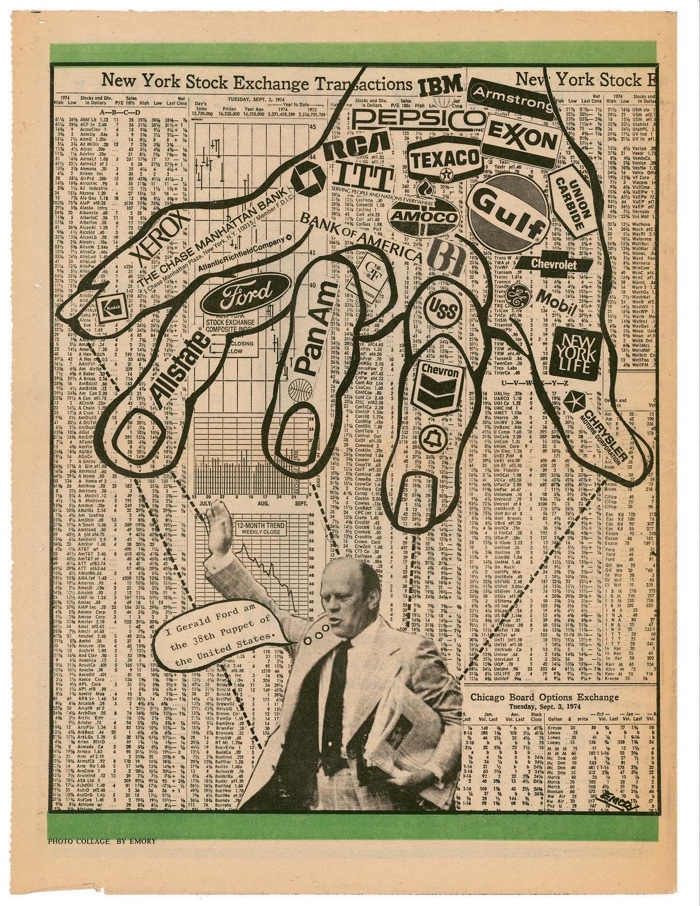

Emory Douglas, Untitled (I Gerald Ford am the 38th Puppet of the United States.), 1974

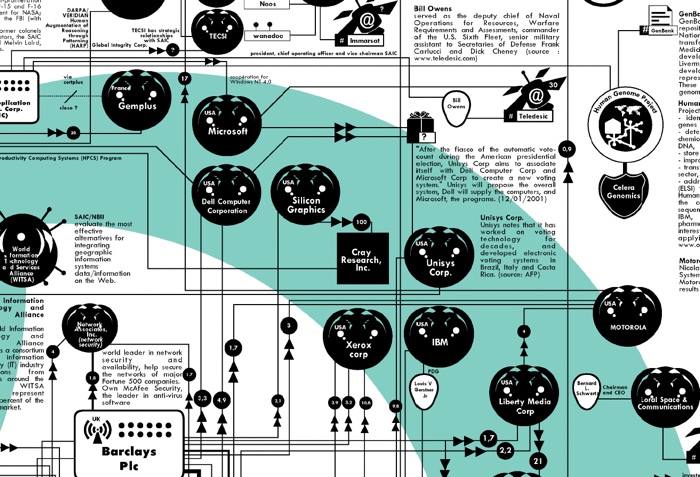

Bureau d’études, Atlas of Agendas (detail from one of the maps)

I greatly enjoyed the book, its critique of design and its ambition to study conspiracy theory without prejudice. Its wittiness, thought-provoking ideas and rigorous research (the sections about the history of conspiracy theory and the development of their imagery were particularly enlightening). The author never trivialises the impact that conspiracy theories have on society and politics, but he believes that we cannot afford to ignore them. Understanding better how they work can help us open conversations on our knowledge systems.

I only have one minor critique: I wasn’t completely convinced by the way the author blurs art and design. There’s nothing new in that kind of connection. In my experience, designers like to think of themselves as artists. The opposite is not so common.