Green Revisited: Encountering Emerging Naturecultures, edited by Rasa Smite, Jens Hauser, Kristin Bergaust and Raitis Smits. Published by RIXC, in collaboration with FeLT – Futures of Living Technologies and MPLab – Art Research Lab. Part of RIXC’s Acoustic Space series.

Green Revisited presents both a series of essays as well as an overview of the exhibitions that took place in 2020 and 2021 around the Greenness studies developed by Jens Hauser.

The contributors to the book challenge anthropocentrism by reconsidering the relations between humankind and non-human agencies, nature and techno-science, and suggest steps towards a more sustainable coexistence with our environment. I have reviewed a fair number of books that have similar ambitions. This one, however, comes with a perspective that I found original, thought-provoking and compelling. And it is mostly due to Jens Hauser’s curatorial vision.

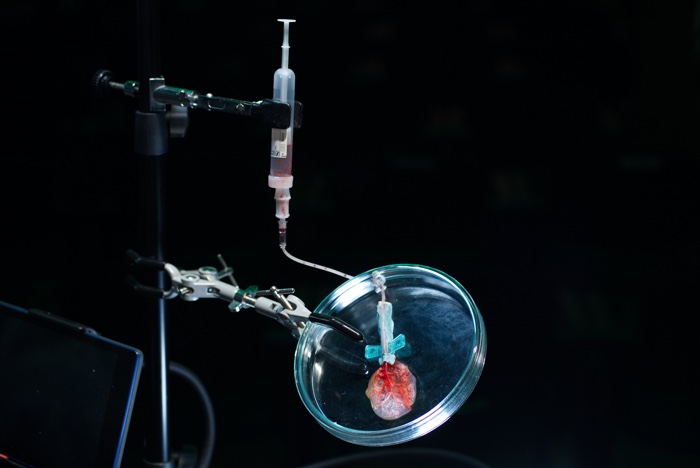

Karine Bonneval, Domestic Tropics

Robert Hengeveld, Kentucky Perfect, 2009/2012,

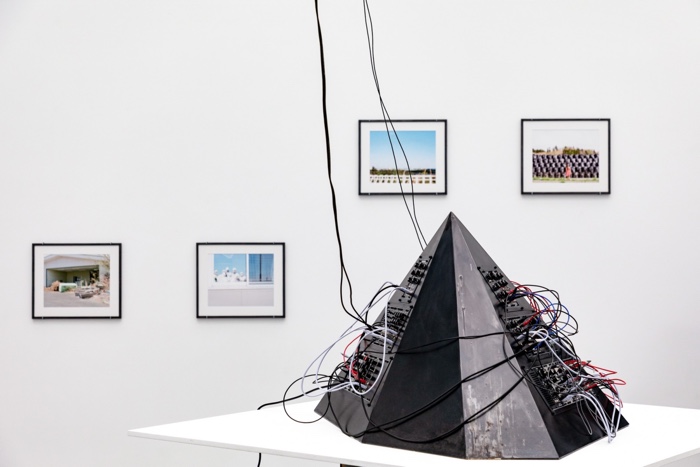

Voldemars Johansons, Uncertainty Drive, 2017

Eva-Maria Lopez, I Never Promised You a Green Garden, 2019. Photo: Kristine Madjare

Bureau d’études, Alien capitalism, Laboratory planet, n°5, Journal, 2016. Photo: Kristine Madjare

Jan-Peter E. R. Sonntag, X from the GAMMAvert cycle, 2019 (GAMMAvert 2006–2019)

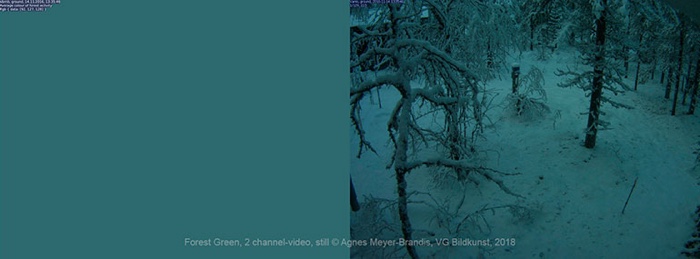

Agnes Meyer-Brandis, Forest Green (Sleeping and Awakening) – Värriö, ground, 12.09.2016, 13:35:51, 2018

The first section of the book Ungreening Greenness. Encountering Emerging Naturecultures includes overviews of the Green Revisited exhibitions (UN/GREEN and OU\ /ERT) curated by Hauser as well as essays that question the claim that green is synonymous of natural. The texts and images assert that today’s understanding of ‘green’ is often little more than a ploy to mask and hide the technical and capitalistic exploitation of living systems, ecologies and the biosphere at large.

For curator Jens Hauser, ‘green’ is actually the most anthropocentric of all colours. Conjuring lexicology, philosophy, biology and other disciplines, Hauser challenges the suitability of green as the ultimate symbolic colour for political ecology. For example, he explains how a plant only appears green to us because its chlorophyll absorbs high-energy red and blue light photons but reflects the rest of the spectrum, including the dominant green, as ‘leftover’ or ‘waste’ that the human eye distinguishes preferentially. Humans, therefore, seem inclined to take this spectral excess as the essence of the plant. Another example of this anthropocentric quality of green is the monoculture, especially when newly planted. They are valued as being “green” but that greenness comes at the cost of biodiversity.

The exhibitions he curated dismantle the ubiquitous greenwashing rhetoric and show the important role that art can play in times of environmental crisis.

Adam W. Brown, Shadows from the Walls of Death, 2019-ongoing

In another (great) essay from that chapter, Adam W. Brown explains the background and significance of Shadows from the Walls of Death, a performance series that investigates the historical, chemical and material agency of Paris Green, one of the most toxic pigments ever produced. The title of the artwork comes from a book published in 1874 by Dr. Robert M. Kedzie. In an effort to raise public awareness about the dangers of arsenic-pigmented wallpaper, Dr. Kedzie sent one hundred copies of his book Shadows from the Walls of Death to Public Libraries across the state of Michigan. Each book contained wallpaper samples. Most of the 100 hundred books were destroyed because of the danger they posed to readers. In his text, Brown shows that the further we removed ourselves from nature the more our attempts to connect with it lead to its destruction.

Ursula Biemann, Acoustic Ocean, 2018

Francois Knoetze, Cape Mongo: VHS|Glass|Plastic|Metal|Paper|Cell, 2013–2015

Rasa Smite, Raitis Smits, Atmospheric Forest. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

The second section of the book, “Ecodata. Technologies of The Ecological” includes artworks and texts that look at green from an ‘ecosystemic perspective’, revealing complex connections between biological, social and techno-scientific systems, living and digital data, artistic and scientific approaches.

In her essay, Yvonne Volkart, curator of the Ecodata exhibition, analyses how artists are using sensing technologies to help us perceive other-than-human modes of existence. The importance of their work lies less in the use of innovative technologies than in developing aesthetic experiences of possible co-existence with our fellow beings.

In All That is Solid Melts into Air. The Atmosphere as Living Space and Visual Field, Jacopo Rasmi comments -among other things- on Italian philosopher Emanuele Coccia‘s invitation to rethink ecology from the point of view of the atmosphere (that is from the connections due to living respiration that plants make possible) in order to define an environmental paradigm that is not founded on the proprietary concept of land or home. On that basis, Coccia proposes to substitute the indoor term “ecology” (home) with different outdoor terms like “atmospherology” (air) or “uranology” (sky). This paradigm shift challenges us to inhabit the unstable and sometimes inhospitable ecosystem of our atmosphere.

In Vertical Fabulations: The Clouds, The Tree and the Cloud, Felipe Castelblanco, examines how the relationship between culture, technology and nature unfolds along a vertical axis of contested spatial relations that connects the ground and the airspace. The paper looks at how the cartographic gaze both instrumentalises and excludes the air space while concealing power and violence operating high above the ground. Knowledge from the ground, however, also brings power. “Unlike most of us elsewhere,” Castelblanco writes, “only familiar with an image of the rainforest taken from high above, Indigenous and farming communities there learn how to perceive the forests from within: Either by planting it, ingesting it, walking it or looking up through its foliage and into the Amazonian sky.”

Vanessa Lorenzo, Mari mutare, 2020. Photo by Konstantin Mitrokhov @Otherwise festival

knowbotiq, Thulhu, Thu, Thu, before the sun harms you, 2020

Clement Valla, pointcloud.garden, 2020

Rihards Vītols, Forest, 2021

Kristīne Krauze-Slucka, Vibrations of the Material Universe, 2020-2021

Kristīne Krauze-Slucka, Vibrations of the Material Universe, 2020-2021. The PostSensorium exhibition, The National Library of Latvia, 2021. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

The last section of the book, “PostSensorium. Futures of Naturally-Artificial Environments”, revises the notion of green from a much broader perspective, inquiring about the mediums, technologies or practices better suited to reveal our sensorium–mediated being and extended reality.

Adnan Hadzi‘s paper Machine Learning and Environmental Justice analyses and challenges the argument that the adoption of AI technologies benefits mostly the selfish needs of a powerful elite.

Even though the author doesn’t contest the utilitarian and authoritarian trend in the way AI is conceived and implemented, he proposes to apply the ethics of care to AI technologies but also to adopt an alternative approach to the current legal system by looking into restorative environmental justice for AI environmental crimes.

Green Revisited: Encountering Emerging Naturecultures was edited and published at the closing activity of the GREEN project. The volume can be ordered by writing at [email protected] (19.00 EUR, plus 6.50 EUR postal costs) or on amazon.com.