While picking up my badge at ISEA2022 in Barcelona last month, I braced myself for 4 days of interesting but intense academic gravity. My first hours at the symposium, however, taught me that the venerable event could be a place for racy ideas. I got a first hint of that during Joan Fontcuberta‘s keynote.

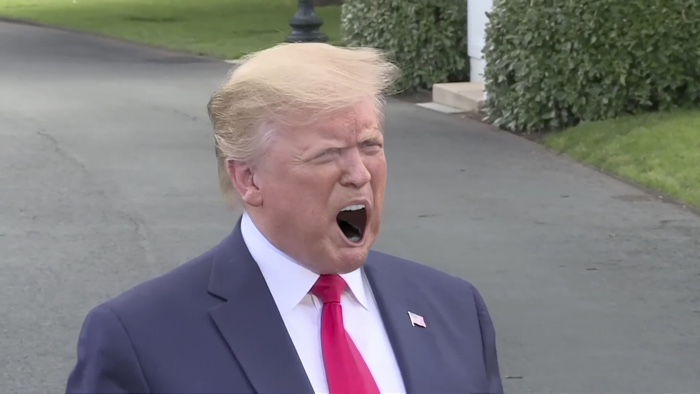

Joan Fontcuberta and Pilar Rosado, Beautiful agony, 2020-2021

Joan Fontcuberta and Pilar Rosado, Beautiful agony, 2020-2021

Joan Fontcuberta’s keynote at ISEA 2022. Photo by Joan Casto, Iconna / UOC (Universitat Oberta de Catalunya)

Throughout his career, Joan Fontcuberta has developed a conceptual photography practice that merges humour with technological experiments and a critical reflection on the concept of evidence. The Age of Monsters, the title of his talk at ISEA, echoes Antonio Gramsci‘s words who, while while he was locked in a prison by Mussolini’s Fascist regime, wrote: Il vecchio mondo sta morendo. Quello nuovo tarda a comparire. E in questo chiaroscuro nascono i mostri / “The old world is dying. The new one is slow to appear. And in this chiaroscuro monsters are born”. Fontcuberta applied the quote to photography, reflecting on the relationships between analog photography (the old world) and the images generated by AI (the new world). For the artist, we should reassess the photographic medium at a moment when analogue photography has shown its inability to respect its promise of delivering truth and memory while the new photography sides with virtuality, machines and algorithms. The term “monsters” can also be interpreted literally. Most of Fontcuberta’s works, after all, explore the strange and the uncanny.

Joan Fontcuberta’s keynote at ISEA 2022. Photo by Joan Casto, Iconna / UOC (Universitat Oberta de Catalunya)

Joan Fontcuberta’s keynote at ISEA 2022. Photo by Joan Casto, Iconna / UOC (Universitat Oberta de Catalunya)

For one of art pieces he described in his ISEA opening keynote, Fontcuberta collaborated with Pilar Rosado to work with a dataset of video-selfies uploaded online by people while they were having an orgasm. The duo used GAN (Generative Adversarial Networks) technology to initiate a process of deep learning aiming to generate false portraits of (non-existent) persons at the moment of climax. This process makes it possible to identify the expressive models characteristic of orgasm and to transfer their expressive typology to any face.

These characteristics were transferred to the faces of four powerful political figures: Donald Trump, Silvio Berlusconi, Dominique Strauss-Kahn and Spain’s former king Juan Carlos I. Each of them has been associated with sex scandals and abuses of power. In the films that Fontcuberta and Rosado made, we see the men experiencing an orgasm in the middle of an official discourse. It’s funny and cringe. Obscene and pitiful. The GAN technology, however, has been applied in a deliberately crude way. The artists’ deep fake experiment was never intended to deceive. What the artists wanted to do with this parody of deep fake was to reveal the mechanisms of deception.

Joan Fontcuberta and Pilar Rosado, Beautiful agony, 2020-2021

Joan Fontcuberta and Pilar Rosado, Beautiful agony, 2020-2021

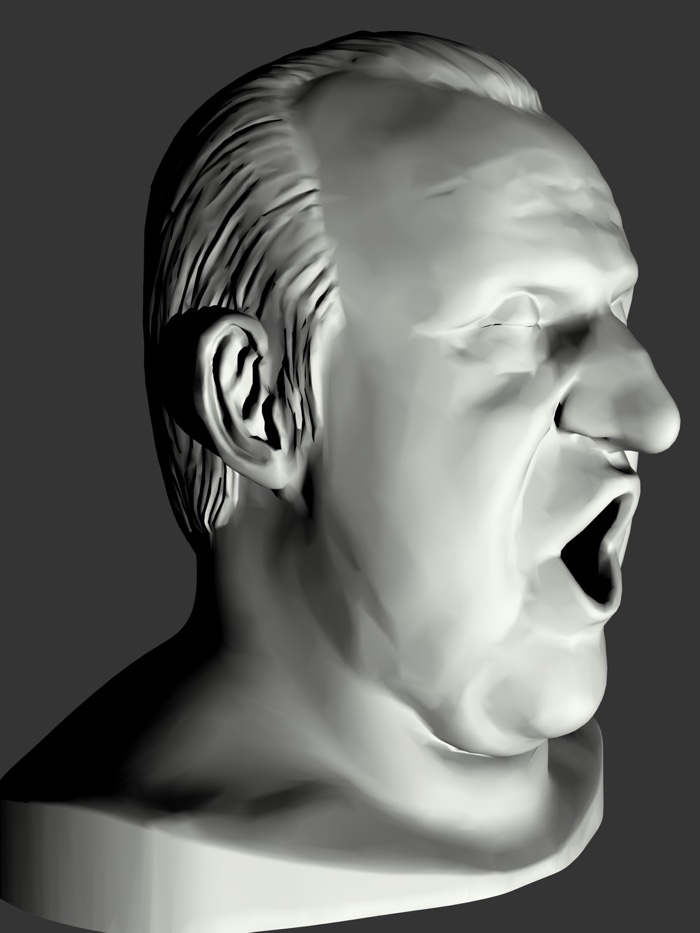

The work is completed by 3D busts of the powerful figures, their faces petrified, as if they had locked eyes with Medusa in the middle of an orgasm.

Unfortunately, the videos are not available online, due to a matter of intellectual property rights. What a pity!

Right after Fontcuberta’s keynote, I attended Ecologies and biotechnical relationships. One of the highlight of the session was Ecopornography in Digital Arts, a paper presented by Zane Cerpina and Stahl Stenslie. Their investigation of “ecopornography” explores how digital arts represent nature in a way that is not explicitly sexual but that nevertheless arouses the viewer and triggers a feeling of excitement similar to the one experienced when exposed to pornography.

Zane Cerpina and Stahl Stenslie, Ecopornography in Digital Arts

According to the researchers, there has been an exponential growth in ecopornographic content in contemporary society and culture due to the massive use of digital media and technologies to the point that nature seems to be a commodity like any other. An example can be found on Instagram where #nature #flowers #naturephotography #wildlife #green are among the most popular hashtags. Similarly, there is an hyperaesthetisation of nature in digital arts. This omnipresence and hyperaesthetisation of nature in nature is not entirely good news because it can lead to a state of exhaustion and indifference.

The objective of the Ecopornography in Digital Arts paper was to call for an in-depth analysis of nature-related content across digital media and media arts. How can digital arts be more critical in exploring and exposing the effect of ecoporn on society? When does ecoporn’s hyperaestheticization of nature lead to an anaesthetic loss of sensation? A new taxonomy of ecoporn can help us reflect on these questions.

Stenslie and Cerpina identified 5 subcategories of ecoporn in digital arts: Nature Pure, Nature Rough, Nature Hurt, Nature Saved and Nature Fake.

Joakim Blattmann, Treverk (9), 2018

Joakim Blattmann<, Treverk 3

Nature Pure can be defined as an idealised representation of nature that aims to appeal and seduce.

The highly popular 360 degrees recreation of Monet paintings, for example. Or Joakim Blattmann, Treverk (Woodwork), a series of installations based on audio recordings of minuscule movements in trees as they are dying.

Studio Rosegaarde, Waterlicht

The Nature Rough enables people to experience the thrills of an instagrammable Apocalypse. Maybe you enjoyed Nature Rough if you were watching the eruption of the La Palma volcano from the comfort of your own home or if you got a chance of being virtually flooded in Studio Rosegaarde, Waterlicht, a large-scale intervention that shows how high the water level could reach as the climate heats up.

Jacob Kirkegaard, MELT

Nature Hurt highlights humanity’s negative impact on nature. An example of that type of nature representation is MELT. In 2013 and 2015, Jacob Kirkegaard travelled to Greenland to make audio recordings of ice melting, documenting how water moves through different aggregate phases, from solid to liquid, changing the combination of molecules irrevocably.

Rihards Vitols, Woodpecker, 2016

In Nature Saved, Man is the hero and saviour of wildlife. Rihard Vithols’s Wood Pecker proposes to replace some of the bird species with artificial ones. He built wooden boxes that replicated the sounds of birds to see if they would scare away the plant-eating insects and help to maintain ecological balance in a forest.

Anna Ridler, Mosaic Virus, 2018

Nature Fake celebrates artificially created nature. As in Anna Ridler’s famous Tulips series.

The researchers also said a few words about the “Ecoporn Personality Test” they are working on. The digital tool for individual self-reflection would allow users to explore their ecopornographic preferences and tendencies.

After Fontcuberta, Cerpina and Stenslie’s talks, life at ISEA got decidedly tamer.

Previously: The long-lost archive of curious animals, Photography Off the Scale: Technologies and Theories of the Mass Image, etc.