Great Adaptations. In the shadow of a climate crisis, by Morgan Phillips, co-director of the charity The Glacier Trust, an NGO that works towards climate change adaptation in Nepal. The book was published by Arkbound.

Great Adaptations. In the shadow of a climate crisis, by Morgan Phillips, co-director of the charity The Glacier Trust, an NGO that works towards climate change adaptation in Nepal. The book was published by Arkbound.

Official blurb: There are great ways to adapt to the climate crisis that confronts us, but there are disastrous ways too. In this book, Morgan Phillips takes us from the air-conditioned pavements of Doha and the ‘cool rooms’ of Paris, to the fog catchers of Morocco and the agro-foresters of Nepal. He makes an often-neglected topic engaging and relatable at precisely the moment the climate movement is waking up to it. A just transition is at stake. Great Adaptations is a provocation, an invitation, and an urgent call to action. If we don’t shape what adaptation is, someone else will.

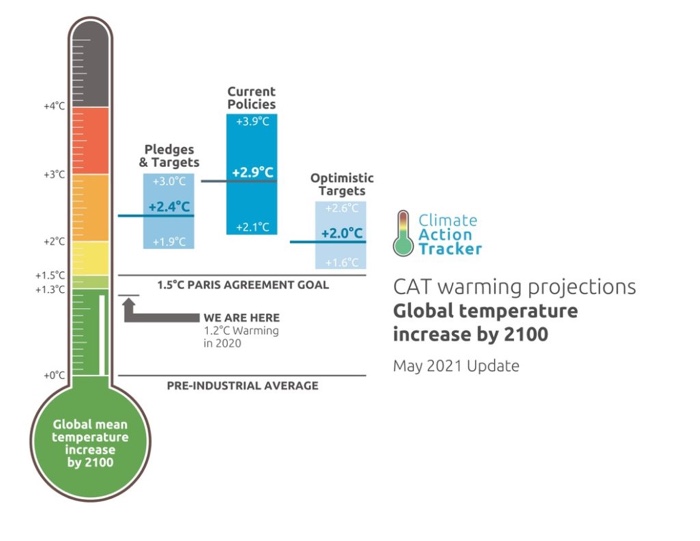

With just the 1.2°C of warming experienced so far, climate change is already destroying millions of (human and non-human) lives. Sadly, many climate experts believe that temperatures are likely to continue rising in the coming decades, bringing unlivable heatwaves, floods and drought.

Morgan Phillips firmly believes that pursuing mitigation won’t be enough if we want to avert a further increase in widespread extreme weather. Mitigation measures will have to be paired with strategies of adaptation.

Climate Action analytics and NewClimate Institute

Great Adaptations covers the most inspiring and the most misguided of twenty-first century adaptations. They are being implemented by individuals, communities, businesses, institutions, governments but also by animals. The book explores the forms adaptations will take and their possible knock-on effects: if we prioritise our own adaptation needs over the wider needs of others (including other species), we might aggravate inequality, injustice and environmental degradation.

One of the many compelling examples of adaptation that Phillips gives is air conditioning in rich areas of the world. Qatar enthusiastically air-conditions stadiums, hotels and even pavements, street cafés and outdoor shopping malls thanks to its abundant supply of fossil fuel energy. Qatar thus practices what the author calls “climate change maladaptation.”

The city of Paris has adopted a radically different approach by extending the opening hours of swimming pools and parks and by making available a series of cool rooms where people who cannot afford air-conditioning can have access to cooler temperatures. Unlike Qatar’s all-air-co strategy, Paris’ measures to deal with extreme heat are communal, accessible to all and do not exacerbate climate disruption nor inequalities amongst citizens.

A wildfire on Evia island, Greece, as the region endures its worst heatwave in decades, which experts have linked to the climate crisis. Photo: Angelos Tzortzinis/AFP/Getty Images, via

Helicopter delivering snow for the sky station in Luchon-Superbagnères, France, in 2020. Photo: Anne-Christine POUJOULAT — AFP

Other examples of maladaptation include ski resorts in the European Alps using snow cannons to spray fake snow over slopes or the rather baffling choice of Luchon-Superbagnères in the French Pyrenees to transport by helicopters snow from high altitudes down to the slopes. These strategies are not only energy-intensive and CO2-emitting, they also help to maintain an impression of normality, a feeling that significant changes to our comfortable and entertained lifestyle aren’t yet needed.

Dar Si Hmad’s CloudFisher. Photo via Atlas of the future

Because fighting for the future of the planet means you have to scare people but also give them a reason to be hopeful and act, Phillips has plenty of uplifting stories of virtuous adaptation up his sleeve. He explains how, in Aït Baâmrane, on the edge of the rapidly expanding Sahara Desert in Morocco, a local NGO called Dar Si Hmad has developed an innovative climate change adaptation project. It involves Fog Harvesting, a simple technology that uses nets or mesh in fog prone locations to catch the humidity as it rolls uphills and channel it into a pipe that brings the drinking water to nearby homes and fields. The technical success has an added social dimension: local women can use the extra time they now have to learn agroecology techniques and attend workshops to improve their digital and literacy skills.

Philipps is often brutally honest. For example, when he explains that many adaptations have been conceived under an assumption that climate change will progress slowly and incrementally, while everything else remains broadly the same. But what if climate change escalates abruptly and ruthlessly? A growing number of people in the climate movement are advancing the idea that ‘Western’ civilisation is on a fast pace to self- destruction. The author’s feeling is that, to have any hope of avoiding catastrophic climate change, ‘Western’ civilisation needs to be disassembled with care and replaced with new, more ecological, just and climate-safe civilisations (plural!)

Elsewhere the author warns against governments’ reassuring stories and in particular their plans to reach Net Zero by 2050 and limit global heating to well below 2°C while relying on almost exponential growth. This “green growth” would in part be made possible thanks to a suite of innovations known as Negative Emissions Technologies (NETs). You know the ones: they siphon excess carbon dioxide out of the air or they involve planting billions of trees while continuing to burn the rainforest in Brazil, DRC or Indonesia. NETs stories are of great comfort but most are neither scalable nor just.

Great Adaptations. In the shadow of a climate crisis is a compact, compelling book. The text flows, the examples are engaging and the design of the publication is lively and fresh. Phillips is rather good at balancing the depressing and the inspirational. Even better, he doesn’t refrain from being a bit political. He warns against adaptation as a top-down process, adaptation that is done for us, for our own good, by politicians and tech innovators, and without too much questioning of our socio-economic systems. His words certainly resonate on this first day of the COP26

The book is not prescriptive. It doesn’t provide the readers with DIY solutions and fail-safe answers. It does however encourage its readers to imagine different, bold and systemic visions of the future that would respect both social and ecological justice. Maybe art has a role to play here?

Image on the homepage: the Eagle Creek wildfire. Photograph: Kristi McCluer/Reuters.