Icebergs, Zombies and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century, by Matthew Soules, associate professor of architecture at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Published by Princeton Architectural Press.

In this book, Matthew Soules argues that, since the early 1980s, the function of buildings as profit-generating investment assets has increased at the expense of buildings’ other roles: shelter and culture. This turbo-acceleration of architecture as wealth storage has an impact on the design, management and use of buildings.

SHoP Architects, rendering of 111 West 57th Street, New York City. Under construction

The architect identified 5 symptoms of how the financial system is reshaping cities around the world: iceberg homes, exurban investment mats, superpodiums, ultra-thin pencil towers and financial icons.

Iceberg homes are a billionaire’s tactic to bypass planning regulations by building story basement extensions beneath their property in highly coveted neighbourhoods. Roger Burrows, who mapped London’s iceberg mansions, called the phenomenon luxified troglodytism. In some cases, exuberant excavations led to the gradual sinking of land and nearby buildings.

San Buenaventura housing complex in Ixtapaluca, Mexico, 2009. Photo: Livia Corona in Architect Magazine

The Exurban Investment Mat is a financial typology that houses middle- or lower-income inhabitants at the periphery of the existing urban fabric, where land is cheaper. Construction costs are reduced through the economies of scale achieved through building large numbers of standardized and repeated units.

Superpodium. Podium towers feature a low-rise base from which one or more towers rise as well as ground-oriented ancillary facilities such as shops, shared amenities and parking. Podiums buffer housing from any messy unpredictability (which constitutes a threat for the investment) emerging from the urban life around it. The podium becomes a superpodium when it is extra-expansive and totally bonkers in its design and the type of luxuries it offers: gigantic pools, ponds, ferns, fish, sunbathing decks by the rooftop pool, exclusive health spa, etc.

The Ultra-Thin Pencil Towers. Behind this self-describing expression are narrow towers whose ownership remains hidden behind complicated networks of intermediaries. Units often sit largely empty, revealing their true function as speculative wealth storage assets among the portfolio holdings of the global elite.

The heirs of the Bilbao Effect, the Financial Icons are used to attract foreign capital in certain areas. Their apparition leads to a rise in land values of the surrounding plots, as their use prospects for retail or residential purposes are improved.

The Ciudad Real airport in La Mancha, Spain which is up for auction with a debt of over 500 million Euros. Via The Independent

A corridor sits half finished at the Ciudad Real airport in La Mancha, Spain. Via The Independent

Residential buildings in the Meixi Lake Development, near Changsha. Via Wired

If financial icons often unsettle whole communities through gentrification, other forms of wealth storage such as ultra-thin towers similarly disrupt neighbourhood, this time through what Soules calls zombification. In “zombie urbanism”, a building serves either as a tax shelter for ultra-rich individuals living elsewhere or as a speculative investment for a real estate fund. The result is a high level of under-occupied buildings and areas which in turn impacts on the vitality of a city. This would seem inconsequential if basic decisions regarding provisions of services and scaling of amenities were not based on historic notions of occupancy.

An even more extreme crisis space, ghost urbanism differs in two ways from zombie urbanism: a much greater amount of vacancy and a perception of failure due to a noticeable and persistent amount of unsold or incomplete housing units that may be in a state of decay. It is at work in countries like Ireland, Spain and China.

In Ireland, hit by the boom and bust of 2007-2008, it wasn’t just houses that brought about ghost conditions but unfinished hotels and shopping malls, phantom golf courses and large amounts of vacant retail and office space. While the situation of ghost urbanism in Ireland has dramatically improved, its ruins can still be found in and around cities. Spain saw a similar frenzy of housing developments but they were accompanied by the construction of huge amount of infrastructure: 13,000 kilometers of extra highway systems, 5 new international airports (some of them sat empty for years) and large numbers of megadevelopments on Madrid’s periphery remained largely vacant.

Multiunit housing shown in 2014 at Calanova Golf, Mijas, Málaga, Andalusia, Spain

Boeri Studio, Bosco Verticale, Milan, Italy, 2014

Chapter 5 was particularly interesting to me. It examines how finance capitalist architecture artificially creates and instrumentalises a certain idea of leisure and nature. Made to look original, sophisticated and unique, the lakes, gardens, beaches and entertainment spaces that bedeck buildings are actually ultra simplified versions of reality. Important particularities of climate, local landscape, interactions between neighbourhoods, noise, pollution, building design, construction quality are ironed out, facilitating a higher degree of control, predictability and stability. Golfscapes, for example, are seen as highly sought after but they remain significantly underused. The increased value of residential property incorporating golf courses shows that golf is primarily a real estate device that facilitates investment.

The section included paragraphs on “greenwashing” in which the author briefly analysed how architecture’s grand ecological promises, from green roofs to recycled building products, are often aligned with real estate marketing strategies regardless of what meaningful environmental benefits they may offer.

Rodney Graham, Spinning Chandelier, Vancouver, 2019. This 4.25-by-6.4-meter re-creation of an eighteenth-century chandelier hangs from the Granville Street Bridge adjacent to Bjarke Ingels Group‘s Vancouver House

Sid Landolt and Peter Dupuis, pictured in 2015, showing off a model of the typical housing unit built in Cambodia as part of their one-for-one home-gifting program with Vancouver House. Photo: Arlen Redekop/Postmedia News files

Another highlight for me was chapter 6 which studies Bjarke Ingels’s Vancouver House condominium tower and what its marketers call the world’s first one-for-one home-gifting program. For every unit sold in the tower, a small house is built and donated to an impoverished family in Cambodia.

The tower is used as a case study to explore the current role of philanthropy in architecture and urbanism. Philosopher Slavoj Žižek would call the individuals behind this idea “liberal communists,” who “claim . . . we can have the global capitalist cake (thrive as entrepreneurs) and eat it (endorse the anti-capitalist causes of social responsibility, ecological concern, etc.).”

Philanthropy is used here as a vehicle by which one hand helps oneself to a lot while the other gives a mere fraction of it in return, affording the satisfaction of feeling socially responsible while the city empties of lower-income individuals. The addition of a chandelier under the nearby bridge was perceived as an extra layer of provocation in Vancouver, a city where artists are being priced out of the housing market.

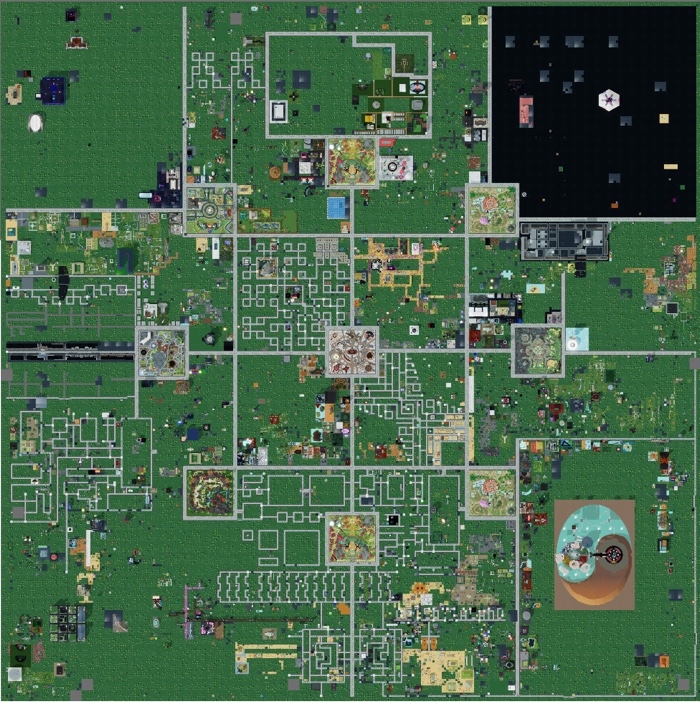

Map of Genesis City, Decentraland. Image via nft plazas

The two-thirds-incomplete Residencial Francisco Hernando, shown in 2014, in Seseña, Toledo, Castile-La Mancha, Spain. Photo by Matthew Soules

I was attracted to Icebergs, Zombies and the Ultra Thin because of the appealing vocabulary it uses and the extravagant reality these words reveal. I read it while my friends back home were losing their homes in heavy floods and then while parts of the country where I now live are being destroyed by fires and while members of a community of animal rights activists I’m part of are busy insulting each other over COVID-19 vaccines. Somehow, I feel that none of that will significantly disturb the investors and developers behind finance capitalist architecture. Reading the book thus felt both frivolous. Yet, I also believe that it is a very pertinent publication.

The book urges architects to better understand the most extreme forms of the financialisation of the built environment, to develop critical and creative strategies that would engage with (or even counter) the mechanics of finance and reassert the roles of architecture in society. Stopping this influx of built structures that abstract themselves from their neighbourhoods and creating environments where various communities can interact and thrive is not the sole preserve of architects, it is something that will require the involvement of developers, politicians, members of the public and even financiers. Icebergs, Zombies and the Ultra Thin doesn’t explain how this could be achieved. But it does a good job at describing the problem. And that’s a first step in the right direction because you can’t break apart a system that hasn’t been described yet.

Image on the homepage: The Spinning Chandelier sculpture installed on the underside of the Granville Bridge next to Vancouver House. November 20, 2019. Photo: Kenneth Chan / Daily Hive