Today, i’m interviewing Taavi Suisalu, an artist whose work i discovered a few years ago in Brussels. Suisalu was part of a group show about Estonian art and technology at BOZAR and his work really stood out. It took me a while till i finally decided to get in touch with him…

Taavi Suisalu, Digital Fossil, 2014

Taavi Suisalu, Noisephony of Lawn Mowers, 2013

Suisalu is particularly active in the fields of sound art, installations and performances. In 2013, he composed a symphony (or rather a noisephony) for lawnmowers and had it performed by a conductor and a group of performers. A year later, he set up a rather “pagan” installation: he connected a rock in the Vorstimäe landscape to a computer in an art gallery, allowing passersby to sacrifice their data in front of his work. In 2016, he created a sound composition based on signals recorded from abandoned satellites and played it back at a speed dictated by the position of the satellites above the gallery. Recently, he also developed a series of works around light and the importance it has taken as the ultimate carrier of information.

Taavi Suisalu, Datafanta, 2020

Right now, Suisalu has a new artwork on show at the University of Tartu Museum. Last autumn, the artist nosed about the museum’s collections, got curious about 19th century measuring instruments, built a seismometer to register the subterranean vibrations of the Vesuvius volcano, collaborated with physicist Siim Pikker to create the 3D-model of a granule of soil picked up in Pompeii and turned this research into an installation that explores how narratives can turn datafication into datafictions.

He currently lives in Tallinn, Estonia, has exhibited his work all over Europe and, in 2014, he received the Young Estonian Artist Prize for curating a distributed exhibition throughout non-existent villages, a project that saw artists reactivate forgotten villages of Southern Estonia with site-sensitive sound performances and installations.

Here’s what our conversation looked like:

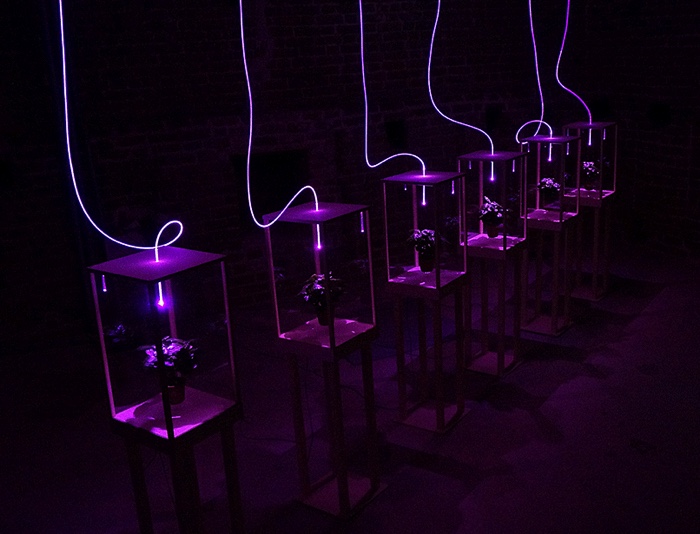

Taavi Suisalu, Waiting for the light, 2018

Taavi Suisalu, Waiting for the light, 2018

Hi Taavi! Let’s start with Waiting for the Light. The installation features plants inside Wardian cases. Could you tell us about how technology is contributing to helping the plant thrive inside its case?

And why do the Wardian cases seem to turn in several directions? What do they respond to?

In Waiting for the Light each plant acts also as a node in the technological network between things, commonly known as the Internet. Whenever we enter an object (device) into this network it becomes automatically a target for automated processes, robots. Each act of communication, a request, towards a plant triggers a burst of growth light via the fiber optic cable connected to the Wardian case. As these cases are quite hermetic, then this light becomes the most existential factor and thus the health of the plants is directly dependant on these automated processes which motives are mostly non-transparent and hence unknown. The rotation of the plants is dependant on how actively the bots are targeting the individual plant.

Taavi Suisalu, Touch of the network, 2019

Taavi Suisalu, Touch of the network, 2019

You write on the project page that “Touch of the Network can be seen as a lighthouse and also as an island in the network between things – the Internet.” Could you explain how the installation works exactly and to which information the light responds to?

Touch of the Network is a work from the same series as Waiting for the light. The series Subocean botlights concentrates on the technological light pulsating in fiber optic cables dropped onto ocean floors or buried under the ground. This light is the main medium for information nowadays and thus it has become as existential to contemporary technological societies as the sun is to the plants. In Touch of the network, the search light mounted on top of a surveyors tripod is also an object in this vast network and once targeted by automated processes, it orients itself and reflects light back towards the physical location where it is being accessed from. If the tripod is being accessed from somewhere in Japan, it orients itself towards that location and so on, acting as a sort of mirror.

Taavi Suisalu, Concrete Constellations, 2014

Taavi Suisalu, Project of Non-existent Villages, 2014

Works such as Project of Non-existent Villages, Touch of the Network, Etudes in Black and others suggest that you enjoy exploring remoteness in relation to connectivity. Why do you find it important to explore technology far away from urban centres and other settings we associate with connectivity?

I try to avoid working only in the studio and find ways to incorporate environments as collaborators in my work. I’d like to think that I conjure small utopias which function simultaneously on metaphorical and technical level. The situations that I construct strive to be actual environments rather than ’no places’ as the etymology of the word implies. Technology-based artworks are reliant on invisible infrastructures present in our urban centers and working in contrasting contexts helps to make these more apparent. Sometimes the setting is essential to the work, at other times it is triggered by where I am showing it. For example Touch of the network was first filmed in north-west Estonia, near Kiipsaare lighthouse which abandons what is normally taken for granted regarding lighthouses — it is not static and has escaped land, it moves around with storms because its foundation is not fixed to the ground. Thus the lighthouse defeats its purpose and communicates an uncertainty which I wanted to be part of the work.

You also seem to be fond of old tools (record player, obsolete satellites, a light box on top of a surveyor tripod, Wardian cases, etc.) and enjoy connecting them with current technology. Why is that? Is it the aesthetics of old objects that so much more charming and understandable compared to what we have today? Or is it simply that you find it important to anchor technology into its own history?

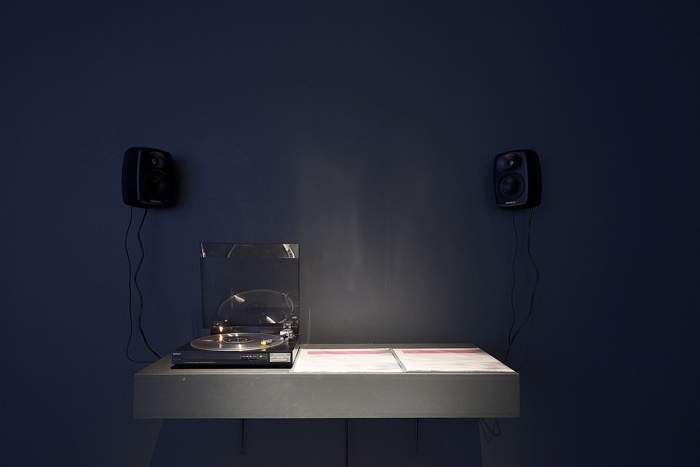

Indeed, in many cases I appropriate old technology because it has had time to build up connotations and the cultural context can be observed from distance. The Wardian cases refer back to the beginnings of globalisation and how they were the first tools which allowed to separate nature from natural environments. Obsolete satellites can be seen as utopian feats of technology that are furthest from our lives but still have direct influence on our perception and behaviour. In Études in Black I wanted to have a record player which speed would be controlled by the same satellites which signals form the basis of the sound composition. I think we are still better accustomed to physical objects and older tools that have visual form whilst current ones are in many cases purely digital, becoming invisible and difficult to grasp.

Taavi Suisalu, Études in Black, 2016. Photo by Stanislav Stepashko

Taavi Suisalu, Études in Black, 2016. Photo by Eva Bubla

Etudes in Black is an archive of cosmic field-recordings and distant photographs which have been collected from the outer layers of technological sphere. These signals were recorded from satellites in orbit which have been turned off. “Due to favorable glitches in their systems these machines have sprung back to operational mode broadcasting information of an unpredictable and improvised nature.” How did you find the disused satellites and how did you found out about their unexpected broadcasts? Could you describe the instruments and apparatus you used in the project?

I was researching for situations where ‘being functional’ becomes ambivalent. I stumbled upon some article by a radio enthusiast who was describing dead satellites. He had dialled onto some radio signals that weren’t listed, but were able to trace these back to historic satellites in orbit which officially were switched off. To record these signals, I used what I call a distant microphone and distant photo camera, which in technical terms was just an omnidirectional antenna built from copper pipes for plumbing connected to a software-defined radio.

Listening to satellites is basically like tuning into a specific radio station while they are visible above horizon. For the ones that broadcast images you need algorithms to translate these electromagnetic signals into pixels. There is a vivid community of radio enthusiasts and satellite trackers and their forums are a wealthy source of information for these kind of things.

Taavi Suisalu, Distant Self-Portrait, 2016

Taavi Suisalu, Distant Self-Portrait, 2016

Distant Self-Portrait employs similar strategies but renders the satellite outputs visually. The kind of portrait is abstract, mesmerising and strangely poetic. How much control do you have on what appears on the screen? Is it “raw data” or do you adjust colours for example?

If we think about portraits, they normally have strong focus in contrast to satellite imagery where they have no focus at all until we give it to them via some interface. Recording an image from horizon to horizon places the photographer in the center, in a way giving it a focus. In Distant Self-Portrait I used raw data from a Russian weather satellite Meteor-M2 and applied an algorithmic realtime animation which was triggered and sustained by human presence in the exhibition space. The animation rendered the landscape into abstract painting-like image dissolving its representative qualities and submerging the portrait into the fluidity of pixels. The images from Meteor-M2 are false color, meaning that they contain two color and one infrared channel. It is up to the receiver to decide which one of the RGB channels gets replaced with the infrared information and this gives you some very different visual styles.

Taavi Suisalu, Noisephony of Lawn Mowers, 2013

Taavi Suisalu, Noisephony of Lawn Mowers, 2013

Taavi Suisalu, Noisephony of Lawn Mowers, 2013

Taavi Suisalu, Noisephony of Lawn Mowers, 2013

I really liked Noisephony of Lawn Mowers. At first, it does look like a prank but it ends up sounding very relaxing and strangely pleasant. It made me realise how, as you write, lawn mowing is a sign of stable and secure living conditions. How did you orchestrate the concert? how much preparation? rehearsal did the project involve? How did the collaboration with conductor Andrus Kallastu go? And how about the performers, where they professional musicians? How did they prepare to “playing” the lawn mower?

The lawn mowers and edgers are quite handicapped in what they can do regarding sound dynamics and hence I knew the composition would need to be spatial in order to be more than just an idea. I produced a visual score for performers that they needed to follow. We had no rehearsals and only a brief intro before the concert and thus the conductor Andrus Kallastu had to manage the situation which he succeeded elegantly. I had met Andrus during my studies at Estonian Academy of Arts where he jointly led a course with then professor Erik Alalooga which involved inventing acoustic instruments and also figuring out how to notate these self-made noisemakers. The course eventually grew into a sound art group called Postinstrumentum which performed on these self-invented instruments incorporating some electronic processing and sounds.

We performed numerous times at Pärnu Contemporary Music Days festival which Andrus Kallastu was organising, thus I knew him quite well before inviting him to collaborate.

Taavi Suisalu, Datafanta, 2020

Taavi Suisalu, Datafanta, 2020

Taavi Suisalu, Datafanta, 2020

Taavi Suisalu, Datafanta, 2020

Taavi Suisalu, Datafanta, 2020

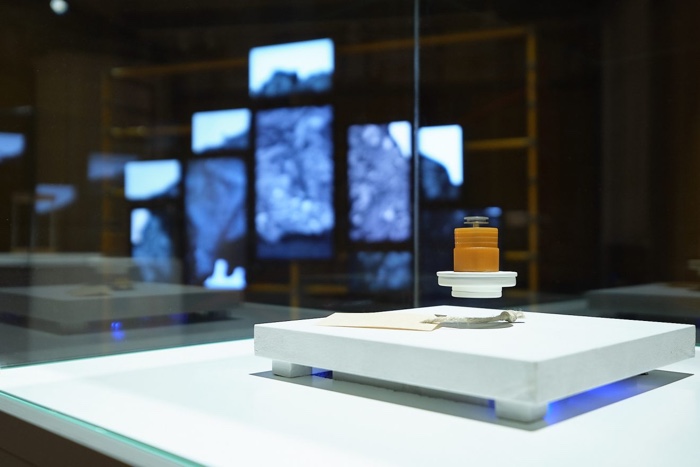

You are currently showing a new work, developed a collaboration with physicist Siim Pikker in the context of Artists in Collections at University of Tartu Art Museum. Could you tell us something about that artwork?

Artist in Collections is a format curated by Maarin Ektermann and Mary Talvistu in which an artist is paired with a museum to produce a work based or inspired by their collection. I was invited to work with the University of Tartu Museum, involve a scientist in the process and produce an exhibition to a space covered by Pompei style wallpaintings. After a short residency in the collection amongst 19th century scientific instruments and models, I found myself reading up on how Pompei was being 3D scanned for digital conservation in response to deterioration by weather and increasing tourism. This also happens on the ground as well as parts of Pompei are being reconstructed, dissolving it into some sort of a physical model.

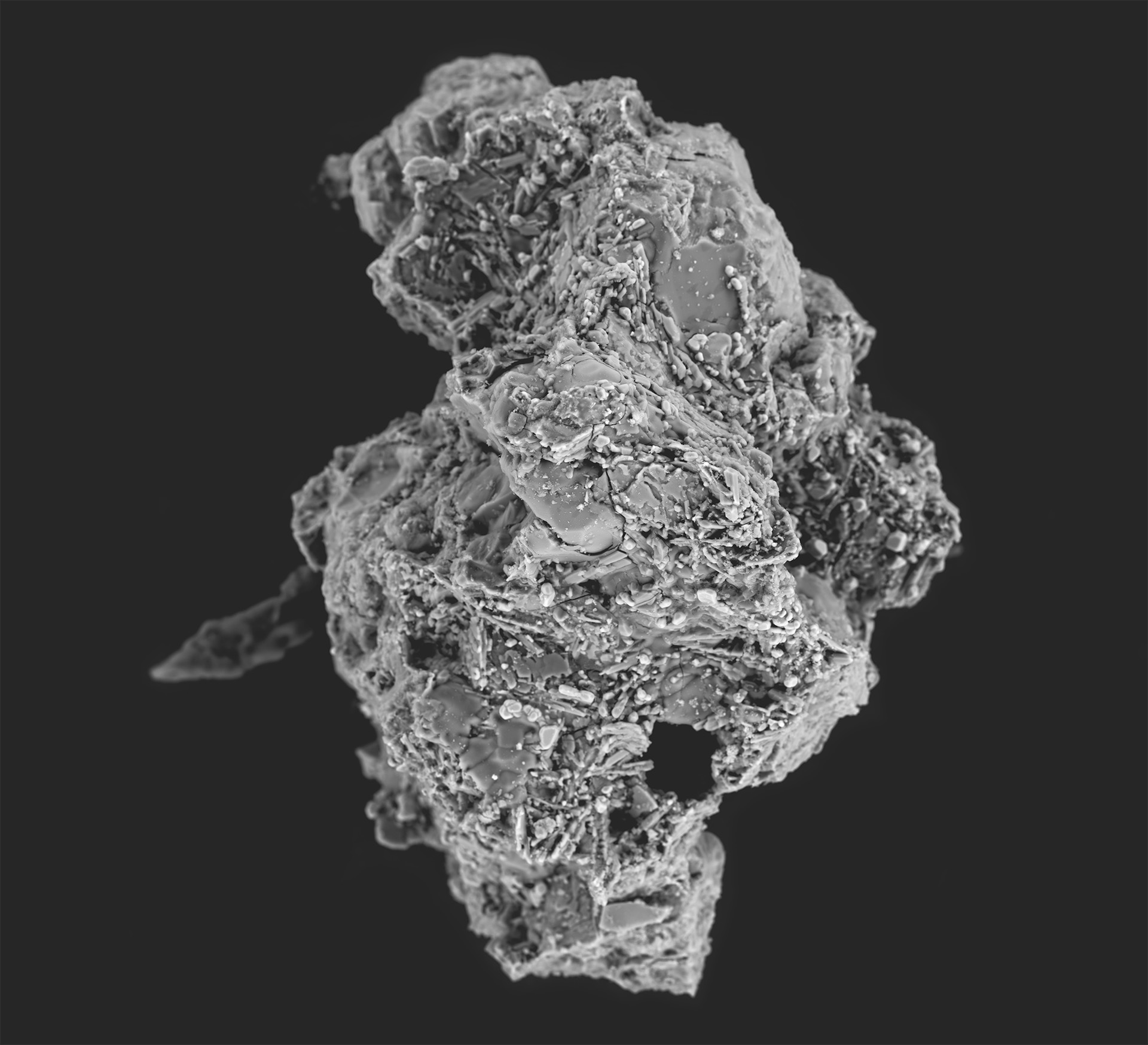

Being fascinated by this uncertainty between the model and what is being modelled, I was curious what role a narrative has in conservation and datafication processes, and if narrative could also be used as an measuring instrument. I planned a field trip to Pompei to collect an insignificant object, a grain of sand, and also to record seismic activity in the vicinity. In collaboration with physicist Siim Pikker we turned the sample into a three-dimensional model using stereophotogrammetry. Whilst being insignificant per se, the small, practically invisible object and its over-sized representation invites to consider their relation and how narratives turn datafications into datafictions. I also proposed to include the grain and its mathematical counterpart to the collection of University of Tartu Museum.

The exhibition called Datafanta features fieldwork documentation, a soundscape based on seismograms recorded in the vicinity of Pompei, the original grain sample and its 3D representation laid out on multiple screens responding to vibrations picked up by the self-built seismograph present at the exhibition space.

Thanks Taavi!

Datafanta is at the University of Tartu Art Museum in the context of Artists in Collections until 27 March 2020.