We, humans and connected objects alike, are producing data so rapidly that storage infrastructures can’t keep up and that some engineers are now looking at the potentials of nature’s most ancient way of preserving information: DNA. DNA digital data storage, the process of encoding and decoding binary data to and from synthesized DNA strands, holds the promise of putting huge amounts of information into tiny molecules. One can see the appeal: DNA is fairly easy to replicate, stable over millennia, far less resource-hungry (or so it seems) than traditional data centers and the technique of storage is getting increasingly cheaper.

Margherita Pevere, Semina Aeternitatis, 2015-2019. Photo by Margherita Pevere

Artist Margherita Pevere has also been experimenting with DNA storage. Her motivations, however, are less utilitarian and more poetical. But they are no less thought-provoking and exciting. One of her ongoing research projects, Semina Aeternitatis, uses DNA storage technique to archive a woman’s intimate experience from her youth into foreign life. Throughout the whole developing and exhibiting process, the artwork explores a series of questions related to wider issues of life, anthropocentrism and ecological crisis:

Can a living body carry the nostalgia of another living body? If you inscribe a human being’s childhood memory onto foreign DNA, will the resulting hybrid body help us understand the increasingly strained relationships between humans and the world they are only a small part of? Will the experiment give us a different, perhaps more compassionate, perspective on other forms of life, big or small, and on the ecological threats they are exposed to?

Pevere collaborated with bioscientist Mirela Alistar and the IEGT (the Institute of Experimental Gene Therapy and Cancer Research at University Rostock in Germany) to convert into genetic code a childhood memory of a woman who chose to remain anonymous. The genetic code was further synthesized into a plasmid which was then inserted into bacterial cells. The bacteria thus store the woman’s transient memory in their own bacterial body. Colonies of bacteria were then grown and cultured to create a large biofilm which, even after it had been sterilized, retains that childhood memory.

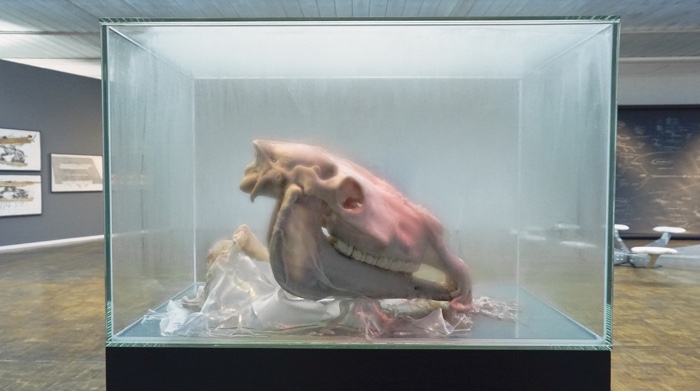

What drew me to the project is not just its ambition of keeping a personal recollection into DNA for a seemingly infinite amount of time, it’s also the aspect of the biofilm. With its flesh tones, wet and viscous surface, it evokes skin and other body matter. It’s disturbing, strangely enticing and makes it impossible to reduce the project to a purely artistic speculation.

Margherita Pevere, Semina Aeternitatis, 2015-2019. Photo by Margherita Pevere

Margherita Pevere, Semina Aeternitatis, 2015-2019. Photo by Margherita Pevere

Margherita Pevere is an artist and researcher whose practice combines scientific protocols and DIY inquiry with aesthetics and a rigorous questioning of the methods and materials she engages with. Semina Aeternitatis is part of her practice-based PhD research at Aalto University, Helsinki. The reason why i asked her to talk to us about her project is that it is part of Experiment Zukunft. This very interesting-looking exhibition, curated by Susanne Jaschko, brings artists, scientists, students and citizens together to imagine probable, possible and fictional futures.

Margherita was kind enough to find a moment to answer my many questions about the work:

Hi Margherita! You started the project Semina Aeternitatis in 2015. Is it an entirely new version you are showing at Experiment Zukunft? How does it build upon or simply differ from the earlier version?

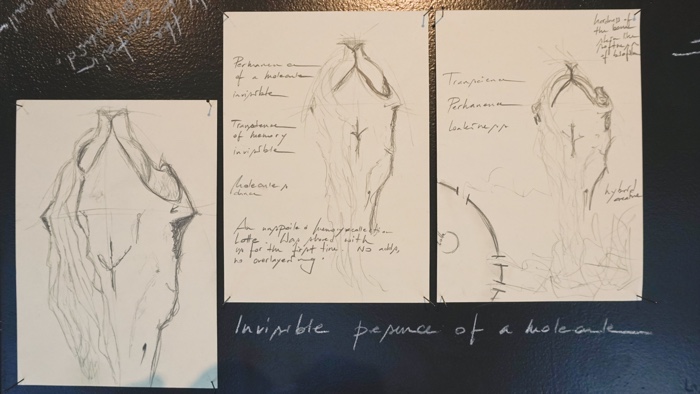

The project has had a long process and the art piece exhibited in Experiment Zukunft evolved from the initial idea. The project started in 2015 with a performances series where I interviewed strangers about the memories they would like to preserve for eternity, with the aim to store such memories on bacterial DNA. The initial idea was to make a series of visual works made of microbial biofilm, but during the process the need for a different embodiment emerged. Hybridity is crucial in my practice and it is interwoven with a visceral fascination for anatomy and biological matter. I wanted to create a hybrid creature that could entwine human memories with bacterial inheritance. The piece called for more liveliness and performativity.

For Experiment Zukunft, I interviewed a lady from Rostock who shared with me a crucial childhood episode which had to do with a horse – I will tell you more about this later. The horse unexpectedly links the woman’s experience with my own. I collaborated with Dr. Mirela Alistar and the Institute of Experimental Gene Therapy and Cancer Research (IEGT). Dr Alistar developed an algorithm to translate the story of the lady’s memory into a DNA sequence. The latter was manufactured as a plasmid, a circular DNA molecule. At IEGT laboratory, we run all protocols to eventually introduce the plasmid by electroporation into the cells of biofilm-producing Komagataeibacter rhaeticus bacteria. The bacteria is now carrying the memory story in their body.

Other artists have worked with DNA as a storage medium, think of the pioneering Microvenus by Joe Davis, or the recent Mezzanine release by Massive Attack. Semina Aeternitatis tackles the friction that arises from our understanding of DNA as a stable molecule, the potential to use this feature for long-term data storage, and the inherent process of becoming we – organic as well inorganic entities – are part of. On the one hand, there is an interplay of timescales I find artistically fertile. On the other hand, such friction may reveal politics and poetics of biological matter in post-human times.

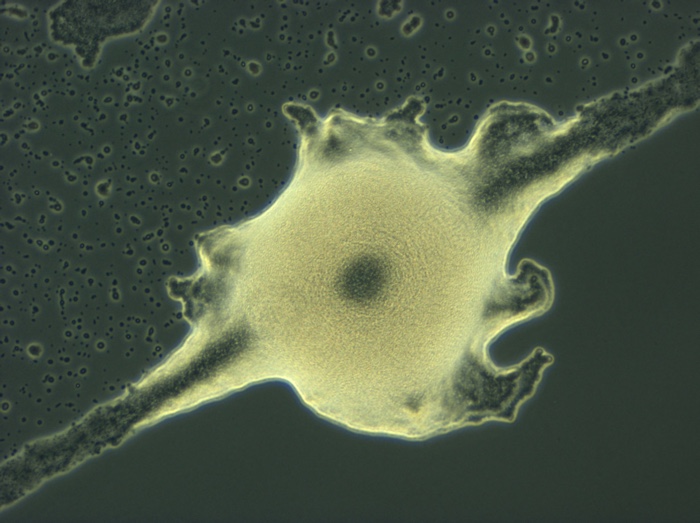

K. rhaeticus microscopy, picture Dr. Alf Spitschak

Margherita Pevere, Semina Aeternitatis, 2015-2019. Photo by Margherita Pevere

I remember hearing Prof Nick Goldman talking about his pioneering work on DNA data storage a few years ago. At the time, the experiment was very costly and looked a bit outlandish. How affordable would DNA data storage be nowadays? As far you know, is this a form of data storage we could consider since the way we store our data nowadays is so energy-hungry?

DNA data storage is still considered a promising technology, although it is far from being error-free and recent research focuses on making it more reliable. However, I would point at an inherent contradiction I see in the narrative of many technologies that are considered “environmentally promising”.

Let’s agree DNA data storage will be more compact and efficient than hard drives. However, it does still require digital interface and the production of DNA still has to be optimised from an environmental point of view. My point here is that it can be more efficient, but it does not affect the system. We live in a system that is data based, where someone sells a huge lie called “the cloud” to someone who buys it, but the aspect I find most concerning is that such system is based on accumulation – one of the pillars of capitalism since its inception – and relies on fossil fuels.

Let’s assume technological development can help shrink our environmental footprint, but until the mantra of more consumption and production are valid without taking into consideration how process the fall-out … There’s a long way to go. Industry is currently about to launch foldable smart-phones, but there is still no solution to the immense dilemma of electrowaste. To be honest, and I am aware this might sound controversial, I wish there were dumps in every city, so people could see with their very eyes what technological materiality is about. I wish people could see black rivers in the parks, smell burning plastic and rotting metals, and relate this to the shiny surface of new laptops. Would that change anything?

To go back to your question, I can be fascinated by the storage and computing potential of molecules, but I think a more radical action is needed towards the environmental footprint of current technology.

I’m interested in the title of the project Semina Aeternitatis, which “is inspired by the human longing for eternity and the desire to permanently preserve memories and information.” In Latin, the title means “Seeds of eternity”. Which made me think about the Svalbard Global Seed Vault and how it also carried this mission of eternal preservation. The project however seems to be threatened by climate change. Do you feel that this gives a new dimension to the work? At least to the way it can be interpreted since our ambitions of achieving eternity seem less and less credible and valid in these unstable times?

You to raise a relevant point here. I should mention first that I have been studying how humans impact the biosphere, including climate change, for 15 years. This has influenced both my own Weltanschauung as well as my work. We also should not forget that climate change has been out there for almost three decades, although its soaring urgency reached the news only in recent times. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault opened in 2008 at what used to be considered a very stable spot, but, only a decade later, unforeseen permafrost melting challenges its stability.

Semina Aeternitaits means both “seeds of eternitiy” and “people of eternity”. This ambiguity addresses both the desire for permanence as well as anthropocentrism of Western culture: I was interested in understanding what link there may be between anthropocentrism, the Christian promise of afterlife, and the process of becoming. In the early phase of the research I considered different manifestations of the desire for permanence. I had long conversation with conservators of audio-visual media, contemporary artworks and ancient documents. I also explored the different approach between myself, a frank atheist, and some dear friends who have faith. Another phenomena I looked at is how Europe is still elaborating the inheritance of the 20th Century and the Holocaust, which came with the promise “Nie wieder!” (ENG: Never again!). Today, the founding values of the society built upon such promise are collapsing before our very eyes.

Again, there is an interplay of temporalities here. We can perceive better if we move away from our everyday temporality, whose fast pace is set by being ever-connected. Climate change introduces an event horizon in such interplay of temporalities, it somehow fractures it.

Margherita Pevere, Semina Aeternitatis, 2015-2019. Photo by Margherita Pevere

Could you tell us about your collaboration with Dr. Mirela Alistar? And did her own background and perspective influence or illuminate the final work and its development in any way?

I met Dr Alistar through the Berlin biohacking scene a few years ago and we have been in touch since then. Next to her academic research in computer science and microfluidics, she cultivates a vivid interest for biological systems and art and is one of the founder of the first citizen lab in Berlin, Top Lab. We have been discussing the project together since a couple of years and she officially joined it in 2018.

Her contribution has been multifaceted and deep. She did not only develop the algorithm to convert the text into DNA sequence, but we also shared important parts of the research and had real fun during the hands-on part in the laboratory. Dr Alistar has an extraordinary mind and is immensely curious, which triggers my imagination. But I think she also helped me find the right thread when I was feeling lost. I really look forward towards what will come out from her laboratory at CU Boulder, where she is starting her professorship next fall.

Margherita Pevere, Semina Aeternitatis, 2015-2019. Photo by Margherita Pevere

Margherita Pevere, Semina Aeternitatis, 2015-2019. Photo by Margherita Pevere

Margherita Pevere, Semina Aeternitatis, 2015-2019. Photo by Margherita Pevere

If the online translating service and I understood correctly the description of the work, the childhood memory of a Rostock woman was stored into a DNA sequence. It was then inserted into the cells of a bacterial strain. The bacteria, which carried the memory, were then cultivated to produce a large piece of cellulose film. This cellulose film looks quite lively and disturbingly organic. Aesthetically, it is miles away from the cold, clean and hygienic aesthetics of the data center that store our digital communication. Could you explain us why you decided to work with this cellulose (you could have stored the information inside a test tube for example)? Does it evolve, change over time?

You both understood correctly. Once we obtained the “memory” plasmid, we ran a series of procedures to combine it with the proper plasmid backbone for the target bacteria K. rhaeticus. We used consolidated scientific protocols, for each step one has to insert the desired molecule into E. coli, grow overnight to amplify it, extract it, run chemical reactions to combine the molecules in the desired way, and so on. Researchers at IEGT laboratory helped us a lot in this process. Eventually, we introduced the plasmid by electroporation into K. rhaeticus bacteria and cultivated the latter to obtain microbial cellulose. The scientific laboratory is a highly controlled environment, where bacteria are mostly perceived as tools and not as living entities.

The ambiguous biotech body of the chimeric creature diverges from the aesthetics usually associated with bioinformatics as to spur the reflection on politics of body and nature. Biological matter is inherently leaky and unstable. There is an inherent ambiguity in the materiality of microbial cellulose. Its resemblance to flesh may trigger abjection, or, conversely, uncanny intimacy. The biofilm in the exhibition has been sterilized and will retain its wet materiality through a controlled environment in the diorama, although it may change over time.

Now that you make me think about it, I also have made back-up tubes containing the molecule for IEGT and Biofilia Laboratory at Aalto University (where I am PhD candidate): such vials are in cold, clean, hygienic environment for archival purposes. But the audience will probably never see them.

Could you also tell us a few words about the lady whose memory will be preserved in this piece of cellulose? Why was it important for you to focus on nostalgic memories?

Thanks to the research of curator Susanne Jaschko, I could interviewed a lady who, in a unique way, positively influenced the life of many people in the region. She asked not to release her identity, so I can’t tell you more details about her. What I can tell you is that she is now in her eighties and is a wonderfully passionate, bright, and determined person. She was eager to understand the process in Semina Aeternitatis and was enthusiastic about the exhibition. I was struck by her strength and charme. I wish can be a bit like her when I grow older!

The lady’s childhood memory, which survives in Semina Aeternitatis, goes back to a formative experience. As a five-year-old, the lady was sent home from the field for the first time unaccompanied and on a workhorse. After the first shock, the horse’s reliability, stamina and equanimity became a life lesson that made her the strong person today: “Trot (through life) like a mare”. The lady paid big attention to pick a memory that was not transformed by further reworking, a sort of primal memory, and it was the first time she shared such episode with someone. She narrated it with beautifully chosen words and vivid awareness of how her experience as a girl entangled with the context and her adult life. It’s a great narrative fabric.

As I mentioned earlier, the lady’s memory somehow overlaps with my own individual experience. I grew up in a semi-rural context, so I am familiar with the one she describes. However, the horse is the strongest link. My horses were companions and not work animals, which makes a difference. But I know so well the moment where you learn to trust the animal, the way the animal knows its surrounding and the way it goes its own way no matter what. However, as any relationship, transpecies relationships may also involve trauma. On my left cheek there is a scar from one of my horses, who involuntarily kicked me in the face. I knew him well and it was an accident, but I had to be determined to overcome fear. I am attracted to scars and this particular one is now part my individual landscape. While preparing the horse skull for the exhibition, I realized that the delicate frontal crests on the skull have the same curve as the scar on my cheek.

Going back to your question, Semina Aeternitatis is about temporalities, materiality, and erosion. Individual memories’ nostalgic lure counters techno-feticism and their evanescence connects different temporalities trough a sense of longing, they manifest desire and vulnerability. They create a space for encounter.

Margherita Pevere, Semina Aeternitatis, 2015-2019. Photo by Fritz Beise

Margherita Pevere, Semina Aeternitatis, 2015-2019. Photo by Margherita Pevere

What can people see in Rostock. How are you showing and communicating the project there?

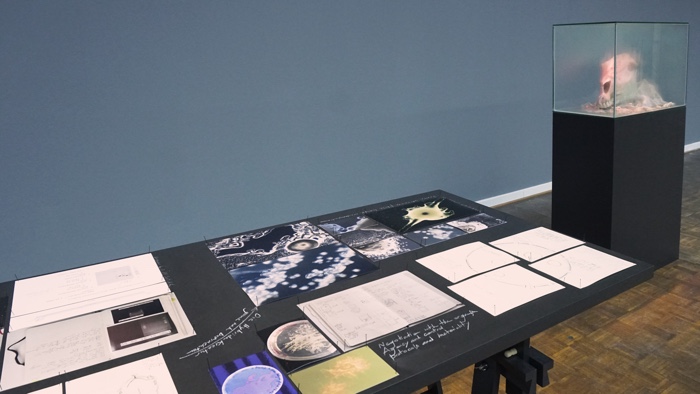

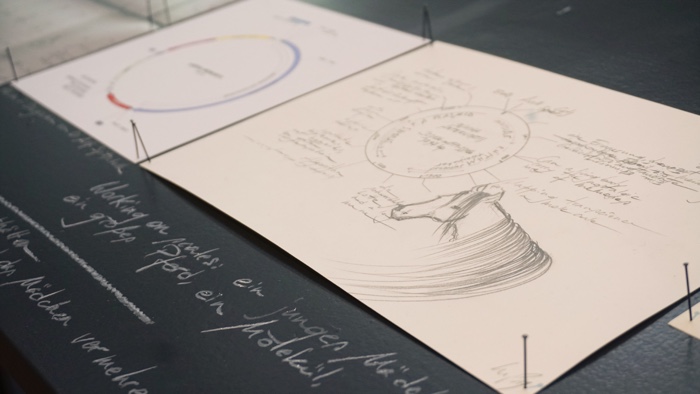

Semina Aeternitatis is an artistic research project and the exhibited art piece is a final manifestation of an articulated research process. It was important to give access to the complexity behind it.

The art piece features a diorama hosting a chimeric creature whose bodily elements grow onto each other in a very organic way. In the diorama, a controlled environment keeps the biofilm moist and creates a feeling of liveliness, while condensation gives a sense of processuality

Next to it, a 3m long table displays research materials including excerpts from laboratory journal, working notes, pictures, drawings, to provide the audience with insights into the artistic and scientific research process.

On April 30th I will join artists Sascha Pohflepp und Antye Guenther and scientists from the Rostock University for a panel with the title “Hybrider Mensch” (Hybrid human).

Thanks Margherita!

You’ve got until 5 May 2019 to see Semina Aeternitatis at Kunsthalle Rostock in Germany. The works is part of Experiment Zukunft, a show curated by Susanne Jaschko.