A VR-essay and performance by artist Geraldine Juárez, PROSPEKT draws disturbing and pertinent parallels between colonialist (and neo-colonialist) bio-prospecting practices and Google’s attempt to get their hands on the world’s knowledge in order to amass, organize and turn it into economically valuable resources.

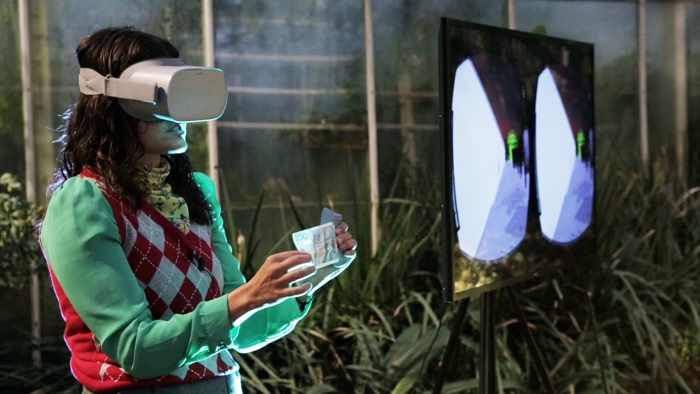

Geraldine Juárez, PROSPEKT, 2018. Photo by Katerina Lukoshkova

The setting for the performance is, very appropriately, the botanical garden in Gothenburg, Sweden. While botanical gardens of the 16th and 17th centuries housed mainly medicinal plants, their 18th and 19th century heirs were dedicated to displaying and labeling the exotic and sometimes economically valuable plant trophies discovered in European colonies and other distant lands. Like many Natural History and Ethnology museums on the old continent today, these botanical gardens are remnants of a colonial period impulse that combines economic and scientific ambitions. They stand testament to the extraction and accumulation needed to produce encyclopaedic projects that aided the organisation of the world. The colonial gaze was determined to scan the surface looking for specimens for study, fixing them as objects out of time and out of place, in the same way that digital documents offer imagings of the world at a distance via screens. This is a prospecting gaze – a wandering ogle that examines, sorts and determines meaning and value.

PROSPEKT is borrowing this marshaling gaze to guide its audience through an exhibition and remind them that organising information is never innocent. We shouldn’t trust a Silicon Valley giant with its archiving, exhibiting and mapping.

Geraldine Juárez, PROSPEKT, 2018. Photo by Katerina Lukoshkova

Poster of PROSPEKT. Design by Jaime Ruelas

Unfortunately, i couldn’t make it to Gothenburg to attend the performance but i contacted Geraldine Juárez to know more about the performance and the motivations behind it:

Hi Geraldine! Your essay “Intercolonial Technogalactic” documents a fascinating experience you made to ‘turn the techno-colonial archive against itself.’ Could you tell us about the experiment and what it showed?

This was the first of three texts I wrote about the Google Cultural Institute. It was originally written as a companion text for a work commissioned by Sophie Springer and Etienne Turpin for the exhibition 125,660 Specimens of Natural History, which focused on colonial natural history collections and the environmental transformations they produced. I used Alfred Russel Wallace, who collected a massive amount of specimens from the Malay Archipelago and brought them to European museums, as an excuse to discuss the colonial impulse manifested in the Google Cultural Institute and their on-going accumulation of “assets” (in googlespeak) from public-funded museums around the world.

I explored and messed around with the interface and content of the Google Cultural Institute for a while and eventually I realised that for being such an ambitious project about “the world’s art and culture,” it was quite weird that there was no information about the history of such a culturally relevant corporation as Google. So I wanted to assemble that history. The text scrolls the interface while searching for its origins as well as the political-economical context in which this “cultural project” has expanded. “Fathers of the Internet” by Femke Snelting and the essay “Powered by Google” by Dan Schiller and Shinjoung Yeo helped me get started and locate the first manifestation of the cultural agenda of Google in a press conference in the National Museum of Iraq and the artificial association with Paul Otlet’s Mundaneum, billed by Google as “Google on paper”.

The expansion of the Google Cultural Institute coincided with their legal problems in Europe, as a spokesperson said to the Financial Times in 2012: We had publishers who were suing us in France and we needed to reach out and invest in Europe, and invest in European culture, in order to change that perception and establish constructive working relations. A year later, the Google Cultural Institute, the performative institution serving as an umbrella for the Google Arts & Culture and The Lab, opened in Paris in 2013.

Geraldine Juárez, PROSPEKT, 2018. Photo by Katerina Lukoshkova

Geraldine Juárez, PROSPEKT, 2018. Photo by Katerina Lukoshkova

At first sight, the ambition of the Google Cultural Institute “to disrupt the gatekeepers of world cultures by offering free digitisation and distribution services to memory institutions worldwide” sounds like a generous and commendable endeavour. Why should we be concerned about it? Why is organising information “never innocent”?

Well, Google has proved that organising the world’s information and make it available to everyone is a business model, not a commendable endeavour.

Google, like all of Silicon Valley corporate culture, sees public services as inefficient infrastructures that they need to make more efficient. So their engineers often invent non-solutions to imaginary problems and present them as “innovations” while wrecking cities, labour laws, privacy, and what is left of democracy and its institutions.

In the specific “partnership” between Google Cultural Institute and public memory institutions, the experience of Google Books should be – but is not – more than enough. It is interesting that while losing interest in libraries and their texts (in part because of the copyright lawsuits against their digitisation activities), Google turned their scanning power and attention onto museums, mostly in aggregating images representing their collections.

This happens under a political and economic environment were cultural policy is reduced to tourism and entertainment, budgets are tied to attendance metrics and similar, with likes and #artselfies on social media constituting part of these metrics, which creates a pressure and a very uncritical “cultural heritage plus digitisation” solution, therefore making it difficult for our weak institutions to reject the offering of the Google Cultural Institute. Even if there is no visible paywall, every image that enters the Google Arts & Culture database is a new asset in a walled garden that – much like all of the Alphabet’s infrastructure and services – is quite inscrutable. In addition, the agreements about these public-private partnerships are not public.

“Organising information is never innocent” means that organising information is always intentional. Amit Sood, the director of the Google Cultural Institute, affirms that a project of this scale and ambition just started casually as a 20% project of “googlers” (meaning workers in googlespeak) who were passionate about art and culture. But I think it is more complicated and has to do with the emergence of the museum as a new kind of relation between people and the state. So in this sense, I think the cultural agenda of Alphabet should be seen as part of this post-democratic condition where information monopolies are increasingly acting like states.

Some other of the many aspects that I found problematic, and conservative like most tech disruption, is the way in which the Google Culture Institute glorifies the past and reproduces the hierarchies of an exhausted European canon. The gigapixel canon of Google basically corresponds to European “high culture” and its masterpieces, led of course by Van Gogh’s Starry Night.

Even the way in which their offices in France are described glorify the cliché version of France. Silicon Valley “tech” culture is very ahistorical but when it comes to their understanding of european culture, it seems that they are very into a high-resolution version of the past and its clichés.

Geraldine Juárez, PROSPEKT, 2018. Photo by Katerina Lukoshkova

Geraldine Juárez, PROSPEKT, 2018. Photo by Katerina Lukoshkova

Why did you chose to work with Oculus go? What makes the headset and its technology significant in the context of PROSPEKT?

PROSPEKT is a “prospect view”, a viewpoint, a wandering ogle that examines, sorts and determines meaning and value. The collection of objects in the exhibition are documents that locate the Google Arts & Culture platform within the history of encyclopaedic projects, its spatial economy and the organisation of “the world-as-an-exhibition” – a concept found in the the work of Derek Gregory about the data-set as a discursive practice and in relation to the spectacular “set-up” of the-world-as-an-exhibition explained by Timothy Mitchell.

Viewing and display techniques, such as 19th century World Exhibitions, botanical gardens and its greenhouses, dioramas, panoramas, archives such as Paul Otlet’s Mundaneum, mapping technologies like the Streetview car, and VR-headsets offering exploratory experiences of scanned surfaces, are all part of a very continuing tradition of gathering, collecting and organising in order to fix objects out of time and out of place in the form of documents. The use of the Oculus in PROSPEKT is the way in which the technical gaze can be performed and do what the prospect view does: explore, scan the surface, seek detail, organise and this time, presenting the world-as-an-endless-digital-exhibition.

Geraldine Juárez, PROSPEKT, 2018. Photo by Katerina Lukoshkova

Geraldine Juárez, PROSPEKT, 2018. Photo by Katerina Lukoshkova

I also wonder how the performance was prepared: for example did the performer rehearse with you beforehand to make sure the quotes and images would appear in a certain order and that no content was neglected? Or was it a discovery for her?

The text in the space was placed based on the script, the curatorial work of Bhavisha and input from Josefina Björk, the performer. The rehearsals were hard because neither Josefina nor I had worked with VR before, never mind trying to come to an understanding of how to perform the essay spatially. She rehearsed with the text already placed and I modified it based on her requests. The work concentrated in familiarising with the space, how to move around, in which order and yes, how to not miss the important parts. During the rehearsals, we realised the text acted as a prompter too so Josefina suggested adding some signs too. These signs (*,**,//) helped her to know, for example, when to look up to read from the sky, when to emphasize something and when to take off the headset (as not all of the performance is with the VR-headset), so these signs acted as a cue for those actions too.

Geraldine Juárez, PROSPEKT, 2018. Photo by Katerina Lukoshkova

And during the performance, did the performer and the public move around the botanical garden? Was there any logic in these movements?

The audience gathered in the the main area of the greenhouse, the Tropical House, where there was a short introduction. After, PROSPEKT guided the audience to the Southern Hemisphere, where the audience took their seats and the performance started. The audience viewed the virtual exhibition through a screen with the feed of PROSPEKT’s gaze. The reason why there is an intro is to establish the greenhouse as the actual artificial and immersive environment containing the performance.

From the screen captures of the VR images, all sorts of quotes emerge: “it was just like an ambulance following a tank”, “there was a time when data was big data and big business”, “Data like plants are taken from the surface”, “capitalism is just a way of organising nature”, etc. Where do these sentences come from?

All of the text in the space is from the script, which is a remediation of the essays I wrote before and some new interest in the relation with bio-prospecting and its evolution on data-prospecting. I didn’t want to separate the texts that shaped the script from the VR exhibition, but to piece them together in a spatial form.

The text is visible because it is meant to be read by the performer, not learned or recited by memory. In this way, it can be read by anyone else who wants to perform it. Potentially, a user could also navigate and read the essay if I distribute PROSPEKT as an “experience” (but I am not really interested in individual or multi-user consumption of VR).

Most of the text in the sky are “quotes” and most of the text on the floor is from the script. Although in some cases there is some of my text in the sky too because it just made sense for the navigation of the space by the performer (e.g., “data like plants are taken from the surface”) or because it was very important!

The sentences you note are from different texts such as Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World by Londa Schiebinger, Capitalism in the Web of Life by Jason W. Moore and a blog post by Dario Gamboni titled ‘World Heritage: Shield or Target?’

Are there strategies we could adopt to resist this monopolisation of knowledge and culture?

There is always going to be a struggle for the monopolisation of resources. This is what politics is about. When it comes to the power that Google, including its cultural philanthropy, exerts over society and its institutions, maybe we need to stop resisting and struggle against it more actively.

Specifically, the so-called public “GLAM” industry – and I want to emphasize the public aspect as in publicly funded – needs some imagination and to stop being impressed with the digitisation fantasies that the Google Cultural Institute offers them in the form of gigapixels, content-management tools and gadgetry and focus a lot more on context, the one thing that the Google Arts and Culture platform can’t aggregate.

I also want to be clear that digitising images, aggregating them in a platform and framing them with “stories” is not “bad” because Google does it. The problem is that it is one of the most powerful corporations on Earth, the ruling class needs to monopolise knowledge to produce and maintain power, and by institutionalising information and related gathering practices they are able to dominate the ways in which images of the world are produced, classified, observed and understood.

For instance, Google did this exhibition called Digital Revolution (you can hire it from Barbican) that features the history of digital art according to Google, but as Rasmus Fleischer pointed out in his review, this is also a show about the absence of Google in the “history” they are exhibiting. If the history of Google is not featured in their own cultural platform and exhibitions, and if the managers of institutions aren’t making an effort to reflect on the political and economic context in which the cultural agenda of Alphabet Inc. has emerged, institutional critique is still a good format to reveal the dynamics consolidating the lack of plurality in platforms, protocols and services where culture circulates. The idea that searching and scrolling decontextualized high-resolution images means “access” is ludicrous.

Could you tell us something about the team that worked with you to develop the project?

I wrote the script and Bhavisha Panchia did the exhibition design of the 3D space based on my script and the related documents and objects on it. She also was in charge of all mediation (like for the contribution we made for the Monoskop Exhibition Library), the curatorial texts and she made sure I met the team deadlines! I modelled the 3D space and displays following her indications. Eva Papamargariti did the additional modelling of plants and palms.

After everything was assembled in Unity and packaged for VR, I started rehearsing the performance with Josefina Björk. She gave me input on the text so there were a lot of changes in the positioning to make it easier for her to read in relation to “the order” of exploring the exhibition. We also worked to avoid directions that produced theatrics and intentionally allowed space for improvisation as the script was not really a play. She helped me with lighting as she is also a very good set designer and we worked together on her wardrobe. Jaime Ruelas made the poster illustration. And Friedrich Kirschner helped me a lot with technical questions to find my way in Unity to the Oculus Go.

Are there any plans to show the performance in other locations? And would that require adapting the content or unfolding of the performance?

Bhavisha and me are working confirming more presentations, in addition to one presentation in Skogen during spring. About adaptation of the work, a small bit of the introduction needs to be adapted according to the venue. The site-specificity of the greenhouse in Botaniska was the ideal as it offered the perfect combination of nature, artifice and glass casing I need, but for instance in Skogen there will be some scenography and panoramic video.

Thanks Geraldine!

On 6 – 31 May 2019, Geraldine Juárez will be heading the Future Landscapes workshop together with Anrick Bregman at the School of Machines, Making and Make-Believe at the National University of Ireland (NUI) Galway.