Have you ever wondered how fun-loving pigs can be? Pigs are, after all, “cognitively complex”. They learn fast, have a sense of time, exhibit empathy, cooperate with members of their social communities, etc. In fact, many of their cognitive capacities can be compared to the ones displayed by other highly intelligent species we tend to respect more: dogs, chimpanzees, elephants, dolphins, etc.

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. Ruby (24 carrot). Photography: Norrie Russell

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. Video still by Brian Mather

Another interesting thing about pig (and other animals) is that they can get bored. If animals are enclosed for too long in an environment devoid of any social, cognitive or environmental stimulation, they “can get depressed and engage in abnormal, repetitive behaviors, like pacing and self-biting, in an attempt to self-stimulate.”

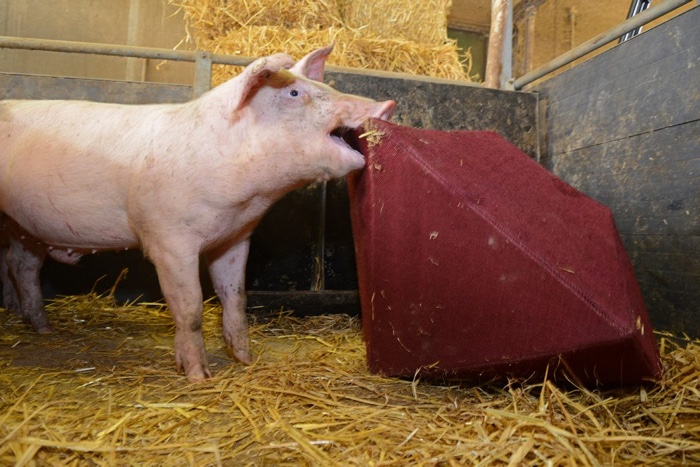

A few months ago, two artists, Andrea Roe and Cath Keay decided to create toys and playful experiences for farmed pigs. They designed eight sculptural objects that, they hoped, would appeal to both humans and pigs. Mostly to pigs though. They crafted toys that make noise, toys that scratch the skin of the pigs, that make them want to sniff, tear apart, munch and explore. Toys that are easy and cheap to replicate by farmers who like their animals entertained and a bit more content with their life in the pigsty.

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. Melon Mines. Photography: Norrie Russell

Roe and Keay didn’t just intend to bring some excitement to pigs’ limited environment, they also wanted to explore animal welfare issues. In fact, the idea for the project drew on the work of Professor Alistair Lawrence, Chair of Animal Behaviour & Welfare at Scotland’s Rural College and The Roslin Institute (the animal sciences research institute famous for Dolly the sheep.) Prof Lawrence’s group is looking at the causes and consequences of ‘positive’ behaviour such as play in farm animals and how enrichments encouraging play can contribute to welfare in farmed animals.

Andrea was working as Leverhulme Trust artist in residence at SRUC and asked Cath to join her to create CARNEVALE, an art-science project that will hopefully make us want to investigate the quality of life of the animals that we eat.

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. Ruby (24 carrot). Photography: Norrie Russell

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. Popcorn Piñata. Photography: Norrie Russell

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. Popcorn Piñata. Photography: Norrie Russell

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. Pigs at play

Andrea Roe is an artist whose work examines the nature of human and animal biology, behaviour, communication and interaction within specific ecological contexts. She is also a lecturer at Edinburgh College of Art. In her work, Cath Keay focuses on sculpture and architecture as two ways to explore constructed form. She has worked with beekeepers and biologists to create artwork altered by the actions of social animals and so-called ‘pest’ organisms, encouraging ants to adapt political sloganeering and Middlesbrough Modern Beehives re-presenting modular Brutalism as functioning beehives for example.

Hi Cath and Andrea! One of the texts you wrote says “Throughout the process of designing and making the objects we were thinking about what matters to pigs.” So what is it that matters to pigs exactly?

AR: Before we began the project, I had little experience of pigs and relied very much on the knowledge of the research technician at Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC) farm. My introduction to pigs was sitting in a pen with a litter of newly weaned piglets during a gentling session and watching how a pig uses his or her snout to experience the world.

One activity important to pigs is rooting. The pigs we worked with were high welfare with plenty of straw for rooting about in and the playthings gave the pigs the opportunity to reveal this and other natural behaviours as they investigated materials with their snouts.

CK: I think animals’ sense of fun is overlooked. The act of playing is ignored or deemed as unimportant, but we know from meeting other animals and pets, that they get enjoyment and pleasure from interacting with other animals, things and even us people. Andrea knew that pigs like natural textures, aromatic plants, and rooting out ‘treasure’ like sticks or stones from the straw in their pens. We wanted to give them a special moment or experience in their lives, and this led to the ideal of a carnevale; a day of festivities apart from the normal run of events.

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. Sweep Sensation. Photography: Norrie Russell

How was the toy design process like? I suspect you didn’t just improvise and throw any type of toys at the pigs. What do pigs respond to in terms of textures, materials, smells….?

AR: It was great fun, we wanted to make objects that could be understood and enjoyed by both humans and pigs so filled them with foodstuffs and named the objects after games or rides at fairs. It was experimental play as we tried to imagine what shapes and forms the pigs would enjoy. I’d run a previous toymaking workshop with favourite things being turnips, sticks and cardboard boxes. Cath and I brainstormed ideas and checked off our list of materials with the research technician who suggested more and described how much pigs love to rip things apart and run off with loose bits.

CK: We didn’t make toys deliberately from the start: we began by designing interactive objects that could be explorative, surprising or fun. After a while we realised that the results resembled party games, or children’s toys- of course the purpose of kids’ games and good enrichment objects for livestock is pretty much the same.

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. House of Many Doors. Photography: Norrie Russell

For Carnevale you worked with animal behaviour scientists, vets and research technicians. What did your artistic approach bring to their own perspective and research?

AR: The whole thing was most definitely a team effort and couldn’t have happened without the support of experienced and skilled individuals… as well as willing pigs! I can’t really say if perspectives were changed but know that images and film of the pigs playing with the toys has being sent out on social media, hosted on websites and used in scientific presentations.

CK: Well, you might have to ask them, but I expect they don’t get much time to try out alternative strategies or things with the pigs. We did try to think of things that are mostly easy to recreate, like the ‘Melon Mines’, or objects that could be reused like the ‘Apple Barrel’, and to include cost-free objects like pine cones or aromatic plants so that sympathetic farmers can try the same things with their animals.

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. Apple Barrel. Photography: Norrie Russell

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. Pig Kerplunk. Photography: Norrie Russell

And conversely, how much did these experts in animal welfare and behaviour challenge any particular assumptions you might have had beforehand about what pigs respond to?

AR: From the start the scientists and technicians were very open to the project and were there on the day participating in the event. Some of the advice was on typical girth measurements of a 4-month old pig and working within the dimensions of the pens. We hoped to learn from the pigs too, the event wasn’t conceived as an end point, more as an invitation to the pigs to interact and for us to observe their preferences. It would be great to revisit the project with new and revised ideas!

CK: We had to remember simple things like the objects must not splinter or damage their mouths. There is no plastic that could be ingested, and we had to be careful with how much fruit they got for the same digestive reasons as you wouldn’t eat melons all day either. Pigs use their noses to explore and so these are very sensitive, and they enjoy tickly/scratchy sensations on their skin. They may never have had rain on their backs but I suspect they would enjoy that.

Why did you chose to work with pigs and not other animals that human eat and exploit such as cows, chicken or fish? Is it because pigs are so smart?

AR: At the very beginning of the residency I was invited to the piglet gentling session, and there is an interesting history of pig behaviour observation at SRUC that I was keen to find out more about.

The Edinburgh Pig Park Experiment took place in the 1970’s, during this, farmed pigs were set free on the Pentland Hills to gain a better understanding of the natural behaviour of the domestic pig. The observations written on the Pig Park Experiment give detailed information as to how free ranging pigs spend their time and prompted the idea of creating objects that would reveal the preferences and capabilities of pigs.

CK: Andrea led on this project and can answer this, but I have worked with bees, ants and so called ‘pest’ marine organisms on art projects in the past. Pigs are smart- in human terms, but other animals are smart at doing what they need to do to inhabit their particular niche. I think us humans don’t want to contemplate the extent of animal sentience and we always understate the smartness of any animal we regard as a potential sandwich filling.

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 201. Fruit Machine. Photography: Norrie Russell

Andrea Roe and Cath Keay, Carnevale, 2017. Apple Barrel. Photography: Norrie Russell

I found Carnevale very moving. It shows that farmed animals deserve to have a great quality of life too. And that this quality of life cannot be summed up in measurement of living space and quantity of food. The work is charming but it is a bit sad too. You brought some joy and excitement (if these words can be applied to animals) to pigs. And then you and the toys were gone and their life went back to normal. Do you think there is a way to bring this kind of ‘enrichment’ of their life to more farms? To other animals?

AR: Ideally by redesigning the housing structures, providing straw and allowing pigs to spend part of their lives outside. The idea behind CARNEVALE was less about promoting the idea of toys for pigs, more about making pigs visible and creating an opportunity for them to reveal their characters and intelligence. In Pig Dreams Pig Life poet Tessa Berring writes from the pigs’ perspective and picks up on the mixed feelings we shared on the day:

“We are pigs at the carnival! Apples is utopia perhaps?

If things stay like this then they cannot stay like this.

Small pen, damp corners. Feeling matters

and makes us matter. Where has normal vanished to?

Does the sky makes sense? Huge rubies filled with carrots?”

CK: All the farmers and scientists we met do intend to give their animals good, happy existences. We hope that the Carnevale project can make it easier for all farmers to aim for this.

By demonstrating a few tactics and objects that can be introduced into routine farming practices, we hope all pigs can avoid the sort of problem behaviours like tail biting and so on that are caused by poor conditions and boredom. There must be ways of designing the routine objects that a pig encounters, such as food pellets, or the bags they come in, that could double up as an enrichment object the pigs can investigate, in the same way as the large cardboard box a present arrives in fascinates small children as much as its contents.

In the essay he wrote for Carnevale, Professor Alistair Lawrence, Chair of Animal Behaviour & Welfare (SRUC and University of Edinburgh) explains that “Welfare science should focus more on demonstrating that improving animal welfare also has benefits for humans.“ Appealing to human selfishness sounds like an excellent strategy. On the other hand, do you think that people would still want to eat pigs if they knew how smart, how playful and how caring they truly are? Or does society love of sausages trump any ethical and emotional consideration?

AR: It’s hard to say what effect more knowledge will have on what people choose to eat. Giving visibility to farm animals and talking about them as individuals would be a good start, and then people connect what they eat with a sentient being. Ethical and emotional considerations on the animal’s quality of life will no doubt follow.

CK: We have to hope that good ethics will be applied to all animal farming when consumers request it and producers acknowledge the welfare requirements and… let’s get to the nub of the issue… the happiness of their stock. We could use emotive language and metaphors but we would end up alienating the people who work daily with farm animals, and these are the folk that can implement enrichment activities for their pigs.

Has your relation to pigs changed since you’ve worked with them?

AR: The more I find out about pigs the more respect and fascination I have for them. Hearing the synchronised calls of the sows to their piglets when it was time to feed was awe inspiring.

CK: Yeah. I had never actually met a pig before, but they are all different. Their reactions to new tastes or sensations like brushes, are obvious to us when they huddled in a gang to gaze at the Popcorn Piñata descending from above, or leapt to where a melon had burst juicy fragments across their pen. Some pigs are bolder and investigated ‘Sweep Sensation’ before their pen mates could summon the courage to come near, while others grabbed the piñata’s tassels and hid them in corners under straw to investigate on their own later.

Everyone can make up their own minds about what is acceptable, or desirable, when they see the animals interact with objects during the Carnevale. People often ask if these pigs can remember that day, however the fact that those pigs were eaten about a month after the event doesn’t occur to them. I didn’t know how short the lives of pigs were either until Andrea told me, so one day is proportionally a much bigger part of their lives than of ours.

I’m also relieved to be so old and tasteless myself now.

I love pigs. Here are more pigs art projects: Interview with Kultivator, an experimental cooperation of organic farming and visual art practice; The Meat Licence Proposal, interview with John O’Shea; Ecological Strategies in Today’s Art (part 1); PIG 05049, a conversation with Christien Meindertsma, Matthew Herbert‘s One Pig and Elio Caccavale‘s Utility Pets.