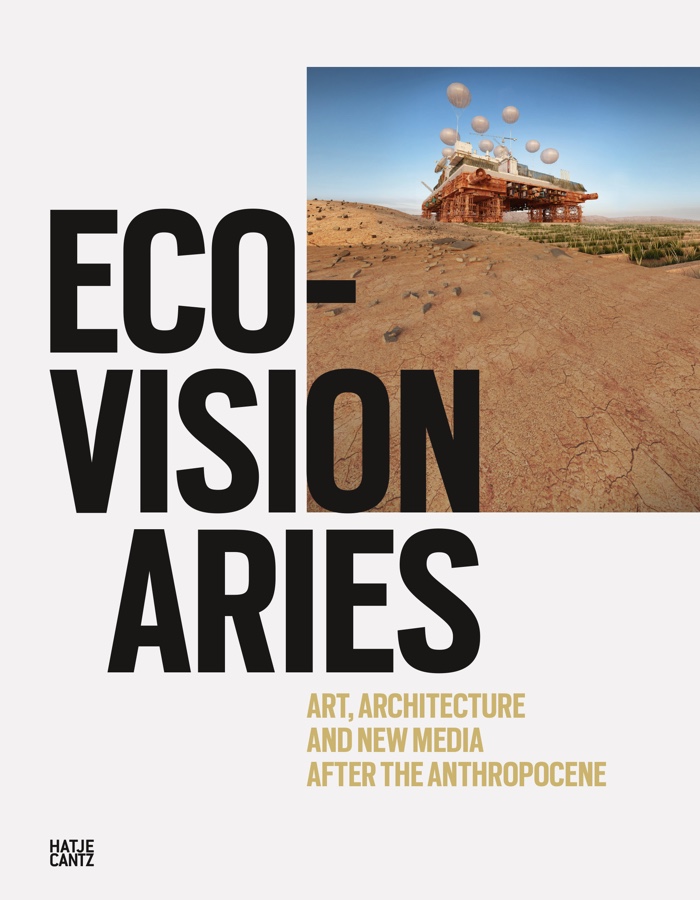

Eco-Visionaries. Art, Architecture, and New Media after the Anthropocene, edited by Pedro Gadanho.

Publisher Hatje Cantz writes: Alternative visions for humankind’s place on earth.

Eco-Visionaries presents contemporary positions in art and architecture seeking answers to current environmental problems that transcend mainstream notions of sustainability. This comprehensive volume is a companion to the collaborative 2018 exhibition endeavored by four participating European museums. Each show maintains a different focus and curatorial approach, and for each, artists investigate alternative visions regarding humankind’s place on earth through video and sound works, paintings, and installations.

While the series of exhibitions presents the works of artists and architects who offer critical reflections on pressing contemporary issues, the book unites research, essays, as well as a survey of the artworks. Besides the historical antecedents of current ecological thinking in the fields of art and design, this catalogue also promotes current approaches that represent alternative visions for future uses of energy, resources, and the environment.

Ant Farm, Clean Air Pod, 1970. Image via Spatial Agency

John Gerrard, Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas) 2017: midday

The authors of this collective publication remind us that one of greatest challenges posed by climate change is that no one knows how to effectively communicate its magnitude and consequences to a non-specialised audience. The facts are there for all to see, they are shared in newspapers, on tv, in books, etc. And yet, the message doesn’t seem to sink in. Everywhere you look, it’s business, meat and plastic as usual. Even when we know the facts, their consequences still seem to be too abstract and distant for most of us to react. Belief that climate change is a hoax has even become normal among members of the U.S. Republican party (on that topic, i’d highly recomment one of the episodes of WNYC’s podcast The United States of Anxiety that explains how this criminal assumption has grown in the U.S.)

Factual knowledge is not enough and that’s where eco-visionaries come in. Eco-visionaries are artists, designers, writers, architects and pretty much everyone else who, confronted with tragic and dispiriting ecological catastrophes, mobilize their create minds to suggest alternative lifestyles, prototype micro-solutions or encourage us to adopt more mindful ways of relating to the world. Through their work, they provide empathetic experiences and help us get a better grasp on complex knowledge.

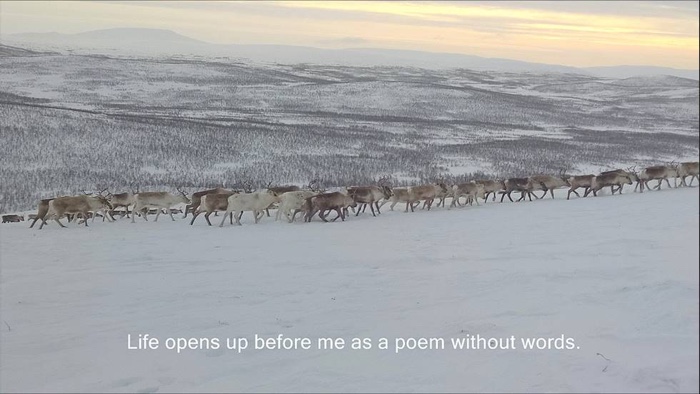

Leena Valkeapää & Oula A. Valkeapää, Manifestations, 2017

With its web tools that visualize internet-induced deforestation, refuges for urban honeybees, mobile architecture that turn desert into vast areas for crops and robots that sonify pollution, the book is a seducing journey to a possible future, one that is not marred by speciesism, petrocapitalism and anthopocentric mentality.

If the works selected in the book (and the exhibitions it aims to accompany) are solid and tirelessly inspiring, the essays are of unequal interest. Maybe i’m not the right public, maybe i read too much about art and the anthropocene but i thought that some of the texts were a bit bland. Others, however are solid. Linda Weintraub, for example, reminds us that the work of eco-art pioneers has gained more meaning and relevance with time; Matthew Fuller fearlessly brings mathematics to the discussion and T.J. Demos penned a fervent, provocative and politically-minded text populated with Guattari, Standing Rocks and warnings against apocalyptic populism and self-annihilation. Finally, i don’t understand the reason why the title of the book has to catapult us in the post-anthropocene. That’s a bold move.

Since i liked the artworks in the book so much, i’m going to introduce you to a short selection of them:

Joaquín Fargas, Glaciator, 2017

Glaciator is a robot roaming around Antarctica. Powered by solar solar energy, its mission is to compact and crystallize the snow turning into ice and then adhering to the glaciers, allowing them to regain the mass they lost as a result of warming temperatures.

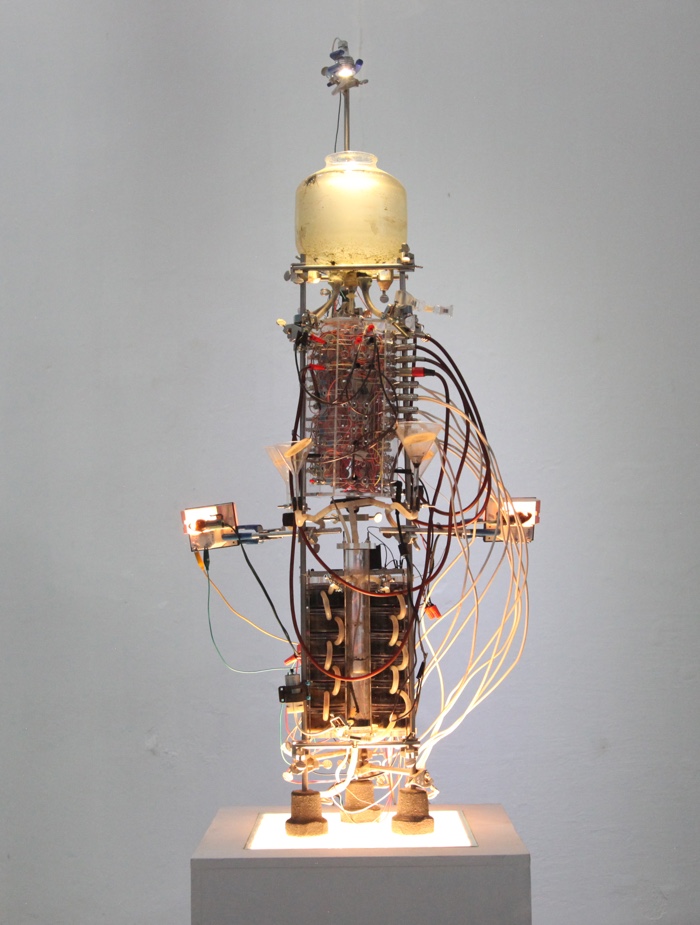

Gilberto Esparza, BioSoNot 2.0, 2017

Gilberto Esparza created an instrument that translates the pollution levels of different rivers into sound.

Microbial fuel cells in the device generate energy from the metabolism of microorganisms found in contaminated water. These cells also estimate the bioelectrical activity of the bacteria while other sensors measure PH, conductivity, temperatures, ORP and other data that define the contamination of the water. The data are then converted into analog signals and translated these values into sound.

John Gerrard, Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas) 2017: midday

The flag of John Gerrard‘s digital simulation work Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas) marks the site of the Lucas Gusher, the world’s first major oil find in 1901, in Spindletop, in the middle of the Texan desert. Gerrard’s flag i made of perpetually-renewing pressurised black smoke. The computer generated Spindletop runs in exact parallel with the real site in Texas throughout the year: the sun rising at the appropriate times and the days getting longer and shorter according to the seasons. The simulation is run live by software that is calculating each frame of the animation in real time as it is needed.

Western Flag symbolizes our reliance on oil. It’s everywhere, it is one of the forces behind climate change and yet it remains invisible. In an interview with the Irish Times, Gerrard describes oil as a “dynamic that allowed for a very particular change in society, allowed for hyper-mobility, changes in food and agriculture. Much of what we think of as ‘real’ is a petroleum reality. Heat, comfort, mobility, it all comes from petroleum.”

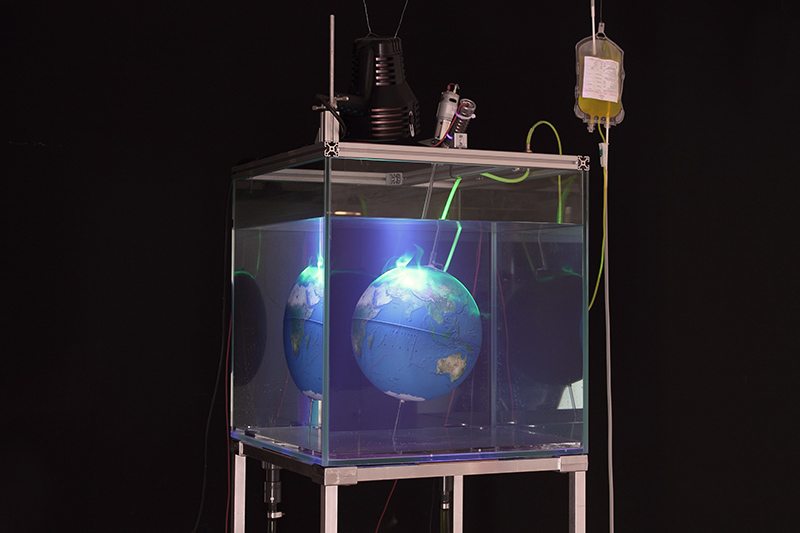

HeHe, Domestic Catastrophe Nº3: La Planète Laboratoire, 2012

HeHe, Domestic Catastrophe Nº3: La Planète Laboratoire, 2012

As an earth globe turns inside an aquarium, a fluorescein tracing dye is released, enveloping the sphere in what appears to be a thin gas or atmosphere that surrounds the Earth. The difference between emissions and atmosphere, the ‘man-influenced’ and the ‘natural’ climate cannot be easily defined.

Kiluanji Kia Henda, Havemos de Voltar (We Shall Return), 2011

In Kiluanji Kia Henda’s video Havemos de Voltar (We Shall Return), a giant sable antelope (an Angolan national symbol) wakes up an archive center. Her name is Amélia Capomba. She finds her body stuffed and displayed in a museum display. She decides she no longer wants to be an artifact at the service of history, intends to push the embalming fluid from her veins, escape from the Archive Centre and return to her past. Amélia’s desire to return can be framed in relation to the ideals of the Angolan Liberation Struggle and more broadly, to the African continent’s need to tell their side of the colonial story.

Rasa Smite and Raitis Smits, Fluctuations of Microworlds, 2017

Wanuri Kahiu, Pumzi, Trailer, 2009

SKREI, Biogas digester (individual plant), 2017

Malka Architecture, The Green Machine, 2014

Exhibitions:

You can already visit Eco-Visionaries at the MAAT—Museu de Arte, Arquitetura e Tecnologia in Lisbon until 8 October, 2018 and at Bildmuseet in Umea until 21 october, 2018; at HeK—House of Electronic Arts Basel in Basel, 30 August–11 November, 2018; and at LABoral Centro de Arte y Creacion Industrial in Gijon, 28 September, 2018–22 April, 2019.