The PAV Parco Arte Vivente, Turin’s experimental centre for Living Arts, is celebrating its ten years anniversary this Summer with The God-Trick, a group exhibition that aims to offer new perspectives and lines of inquiry on the Anthropocene.

Critical Art Ensemble, Environmental Triage: An Experiment in Democracy and Necropolitics, 2018. Photo: © Filippo Alfero for PAV – Parco Arte Vivente

The exhibition title is borrowed from a text by Donna Haraway, the most quoted figure in the anthropocene conversation. The philosopher calls “god-trick” the view that knowledge is only achieved by adopting an objective, disembodied, impartial view from nowhere. She believes this claim to the “objectivizing” of the real is an illusion, for knowledge is always situated geographically, historically and culturally.

The artworks in the exhibition “have the role of reminding us that there is nothing natural, nothing objective, nothing inevitable about the processes of capitalist accumulation, thereby encouraging us to go beyond the confines of thoughts that prevent us from seeing any alternative to the system.”

The exhibition has some very strong works. Whether they speculate on alternative energy supply, un-peel the strata of nature and industrial history beneath our feet or invite us to turn neglected public spaces into community garden, the pieces exhibited demonstrate that there are indeed artists, thinkers and citizens who are willing to look critically into matters that threaten life on this planet. They are not the first ones to do so. We’ve been warned time and time again and as far back as in the 19th century when polymath Alexander von Humboldt drew on his studies in geography and exploration of the South American rain forests to predict deforestation and harmful human induced climate change.

The God Trick will hopefully encourage us to turn these warnings into meaningful individual and political actions.

In the meantime, here are some of my favourite works in the show:

Critical Art Ensemble, Environmental Triage: An Experiment in Democracy and Necropolitics, 2018. Photo: © Filippo Alfero for PAV – Parco Arte Vivente

Critical Art Ensemble, Environmental Triage: An Experiment in Democracy and Necropolitics, 2018. Photo: © Filippo Alfero for PAV – Parco Arte Vivente

Critical Art Ensemble, Environmental Triage: An Experiment in Democracy and Necropolitics, 2018. Photo: © Filippo Alfero for PAV – Parco Arte Vivente

Critical Art Ensemble, Environmental Triage: An Experiment in Democracy and Necropolitics, 2018. Photo: © Filippo Alfero for PAV – Parco Arte Vivente

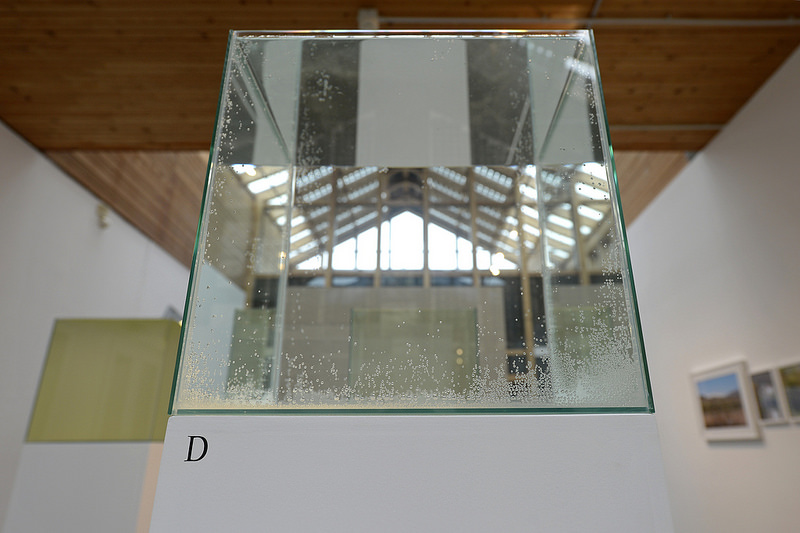

The Critical Art Ensemble collaborated to the discussion with a fascinating research on the theme of necropolitics. The term is defined as the use of social and political power to dictate how some people may live and how some must die. When applied in a hospital context, the concept can be compared to the process of triage which determines the priority of patients’ treatments based on the severity of their condition. There, where resources are plentiful, the person with the greatest injury receives the greatest share of resources and is treated before others of lesser injury. In the case of war, where resources are limited, the typical application of triage consists of designating who is most likely to survive an injury for the longest period of time, and they are treated first. Those with the worst injuries and those most likely to die, are treated last, if at all.

What might be the consequences of triage when you apply it to wildlife and the environment? How do we decide to use our limited resources? Which damaged ecosystems should be prioritized for remediation? Which one are we going to wash our hands of? Do we use the hospital model, the war model, or something else?

The work is based on a research started in April 2018. Collaborating with a scientist who has a deep knowledge of the biology of the waters in the area, the artists and PAV took some water samples and had them analyzed to evaluate the type of pollution and the presence of micro-organisms and plant species in the water. They selected 4 ‘candidates’ to remediation:

– a lake in reasonably good conditions, both chemically and ecologically, but it needs to be protected and cleaned up;

– a small pond in fairly good health. It would be cheap to regenerate its waters;

– a river that’s chemically healthy but suffering in terms of ecology. It would be costly to clean and protect it but many more living organisms depend upon its health;

– an aqueduct that needs to be upgraded in order for the quality of the water to improve. People would then drink more tap water and be less inclined to buy plastic bottles.

Visitors of the exhibitions are invited to vote for the water pond or stream that needs to be prioritized. I found it very difficult to chose: you get maps, facts, samples of water in tanks to help you make an informed decision. I ended up cheating and casting my vote for two of them.

The CAE explains in the catalogue of the exhibition:

Our experience is that this conversation will not solely be grounded in reason, but will contain copious amounts of emotion, aesthetic prejudice, desire, and for some, metaphysical considerations.

Conversation is one of the key aspects of this work. It leaves space for exchanges of views about local resources and landscapes and, beyond that, it forces us to reexamine our ecological, societal and even political priorities.

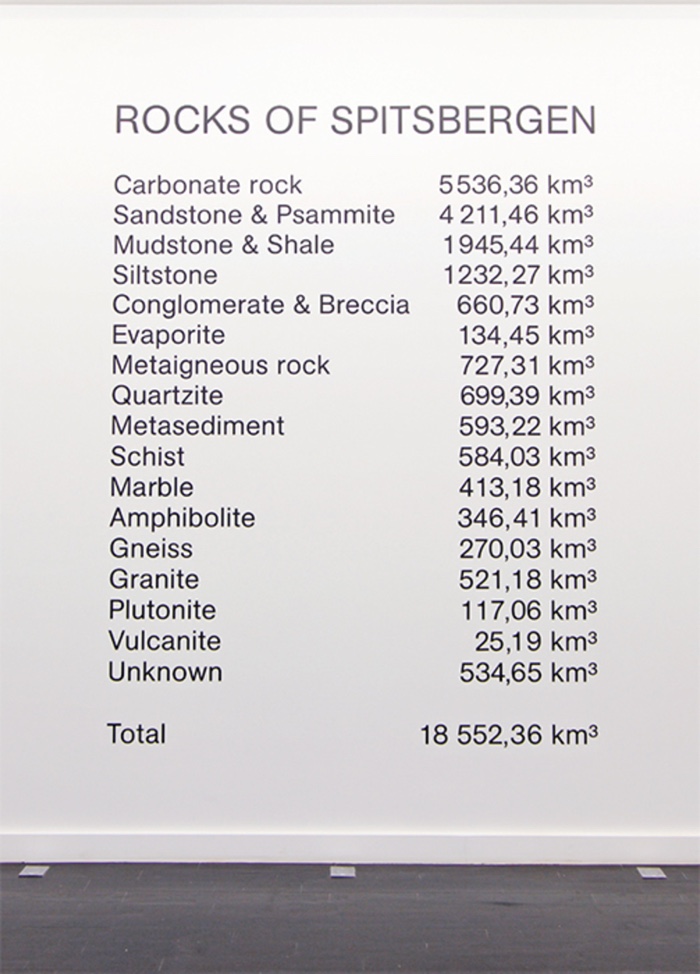

Lara Almarcegui, Rocks of Spitsbergen (Svalbard), 2014. Photo: © Filippo Alfero for PAV – Parco Arte Vivente

Lara Almarcegui, Rocks of Spitsbergen (Svalbard), 2014. Image

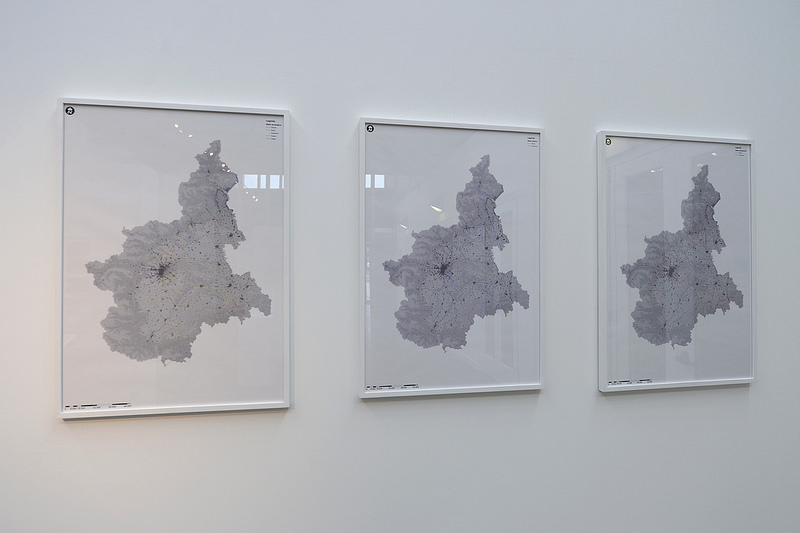

Spitsbergen is the largest island of the Svalbard archipelago in northern Norway. Using figures established by the Norway Environment Agency, Lara Almarcegui made a poster listing the rock types and how many tons there are of each in the island’s bedrock.

Rocks of Spitsbergen brings together the region’s long and slow geological formation and its history of prospecting, drilling and mining the mineral resources. With estimated coal deposits of some 22 million tons, the area around Longyearbyen on Spitsbergen has two active mines, and further extraction might start soon. The dry inventory of the volume of the mineral resources raises questions such as: What will remain of the island if its rocks are extracted for minerals? Is our need of minerals worth the destruction of a territory? Who has the right to decide what to do with the ground beneath our feet? Or, more generally, how to manage our natural resources?

Michel Blazy, Forêt de balais, 2013–18. Photo: © Filippo Alfero for PAV – Parco Arte Vivente

Michel Blazy, Forêt de balais, 2013–18. Photo: © Filippo Alfero for PAV – Parco Arte Vivente

Many of Michel Blazy‘s installations feature organic elements that take over and transform the artworks over time. His “Forêt de balais”, literally “forest of brooms”, features brooms made of broomcorn, a type of sorghum used for making brooms. The domestic objects are planted on the ground and, gradually, they start germinating and growing until they return to their original, living state of plants. After the exhibition, the brooms turned plants again will remain in the park at PAV and become an integral part of its landscape, remembering us that nature can, with time and obstinacy, reclaim the areas which humankind had confiscated.

Bonnie Ora Sherk, A Living Library Is Cultivating The Human & Ecological Garden, 2018. Photo: © Filippo Alfero for PAV – Parco Arte Vivente

Bonnie Ora Sherk’s Living Library is a framework and methodology for planning the “ecologizing” of specific areas.

Sherk is a landscape architect, educator and artist who has been producing visionary ecological work since the early 1970s. In 1981, she founded A Living Library, a community project that enrolls the help of local communities to turn public open spaces that have fallen into disuse or dilapidation into ecological wonderlands and landscapes. Each green site is unique and kept thriving with hands-on learning activities that explore the deep connections between biological, cultural and technological systems.

Go and visit The God Trick if you’re in Northwest Italy this Summer. It is not only intelligently curated but it will also demonstrate, if needed, that the best response to the current heat wave doesn’t lie in more air conditioning and more barbecued meat.

The God-Trick, curated by Marco Scotini, remains open until 21 October 2018 Parco Arte Vivente (PAV) in Turin.