Bernd Oppl, Crooked Building, 2015

Evelyn Bencicova & Adam Csoka Keller, ASYMPTOTE

AJNHAJTCLUB, an exhibition at frei_raum Q21 in Vienna, celebrates the men and women who came from Yugoslavia (now Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia, Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina) to work in Austria.

50 years ago, on 4 April 1966, the two countries signed a contract that regulated the legal and voluntary migration of labor towards Austria, and created the Gastarbeiter (guestworker) phenomenon. Austria needed unskilled workers to support the surge of industrialization and Yugoslavia benefited from the money that workers sent to their families back home.

One of the articles of the agreement stipulated that the newcomers had the right to keep and develop their own cultural identity into workers social clubs. The clubs offered immigrants a way to connect to their roots as much as it kept them away from the street.

That’s from these clubs that the slightly baffling name of the show comes from. AJNHAJTCLUB means oneness or unity club in english. The German word for it is “EINHEIT CLUB” and AJNHAJTCLUB is the phonetic transcription of the word. Because many newcomers to Austria could not speak German this type of spelling was often used to simplify verbal communication between cultures. One of the artists in the show, Goran Novaković aka Goxilla, actually set up a class room in the space upstairs so that visitors can learn to pronounce correctly a look-a-like-language that they can not actually speak.

AJNHAJTCLUB is a contemporary “club” that “aims to unite these migrants’ past and present narratives using contemporary artistic practice and research, providing a look back to inform the future. Although more familiar from black and white imagery, the guestworker phenomenon is still alive. The exhibition shows this phenomenon in full color, complete with animated 3D avatars, modern folklore, interactive performances and contemporary interventions.”

It is tempting to see parallels between the focus of the exhibition and the current refugee situation in Europe. The context is quite different though. While Gastarbeiter came as a result of an agreement between two countries, the people who arrive in Europe today have been forced to leave their home because of the consequence of wars and other global developments.

AJNHAJTCLUB is a brave, timely and intelligent show that celebrates immigration and the economic and cultural contribution it can bring to a host country (i only wish that Trump, Brexiters and their likes across the world would visit it.) AJNHAJTCLUB could have been an exhibition full of gravity, nostalgia and anxiety. And indeed it sometimes features moments as serious as the times we are living but it is mostly a show full of humour, lightness and self-irony.

A quick walk through some of the works exhibited:

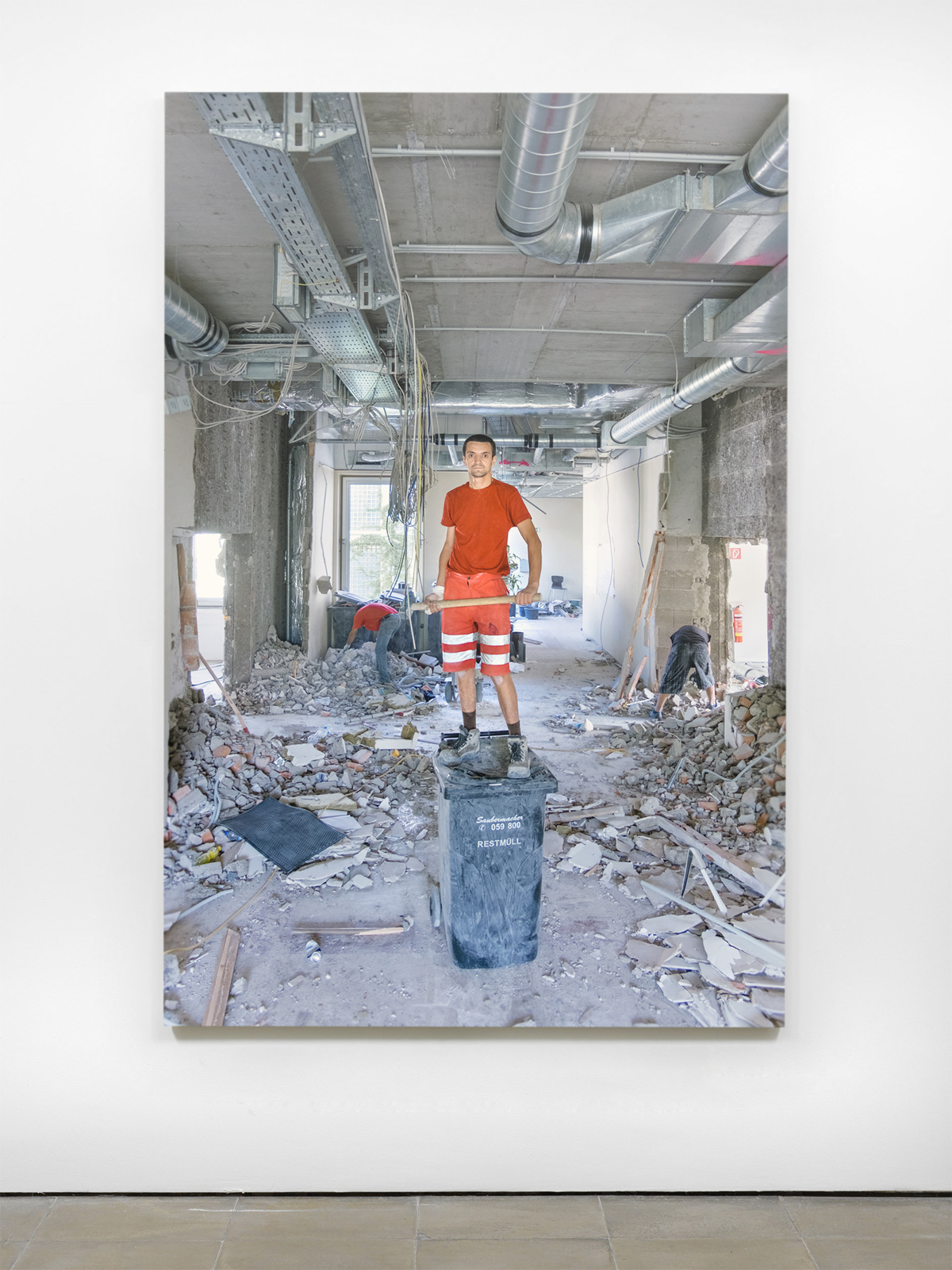

Milan Mijalkovic, Arbeiter mit Vorschlaghammer (Worker with Sledgehammer), 2015. From the series Arbeiter

Milan Mijalkovic‘s large format photograph Worker with Sledgehammer portrays a worker on a trash bin in the middle of a construction site. The heroic posture and the bin used as a pedestal celebrate anonymous migrant workers who, every day, physically erect buildings throughout the country.

Milan Mijalkovic, The Monument of the Working Man

The bitter-sweet Monument of the Working Man was one of my favourite works in the show.

The video shows balloons that are seemingly blown up automatically by a machine hidden inside the beige pedestal. But the balloons are actually inflated by a man who barely fits inside the box. The artist found the worker in front of a store where workmen gather and offer illicit labor. A Romanian bricklayer agreed to do it, demanding 1 Euro per balloon.

The deflated balloons on the floor are a sign that the party is over. In this work, the artist adopts the role of the brutal employer, reminding us of the reality, where this kind of

exploitation is carried out on a daily basis. Using people to operate the machines in closed boxes is cheaper than using a reliable machine-operated system.

Addie Wagenknecht, Optimization of Parenthood, Part 2. Photo: Bernd Oppl

Addie Wagenknecht’s Optimization of Parenting is a robot arm that gently rocks the cradle whenever the baby cries and the mother is at work. The work pays homage to the women who left their home to work in Austria back in the 1960’s. Some of them had to leave their children with the grandparents. The installation also alludes to the fact that in these time of growing automation when many jobs can be done by machines, the roles and tasks of guestworkers are changing.

Bogomir Doringer in collaboration with Nature History Museum Vienna, Curated by Nature, 2016. Photo: Max Kropitz

Bogomir Doringer in collaboration with Nature History Museum Vienna, Curated by Nature. Opening of the exhibition. Photo Foto: eSeL – Joanna Pianka for Q21

Because migrants are often compared to migrant birds, Bogomir Doringer, an artist but also the curator of the exhibition, asked experts from the nearby Natural History Museum to select a series of birds whose narrative could be compared to the one of the guest workers.

Some of the birds in the showcase go back each year to the place they come from. Others stay in the new territory and become part of its ecosystem. Either because they find better living conditions or because their original habitat has changed for the worse. Some of these birds are called “invasive species.”

Interestingly, one of the birds selected is the Eurasian Collared Dove. The species came from Asia via the Balkans to Vienna and is now regarded as a typical Viennese bird.

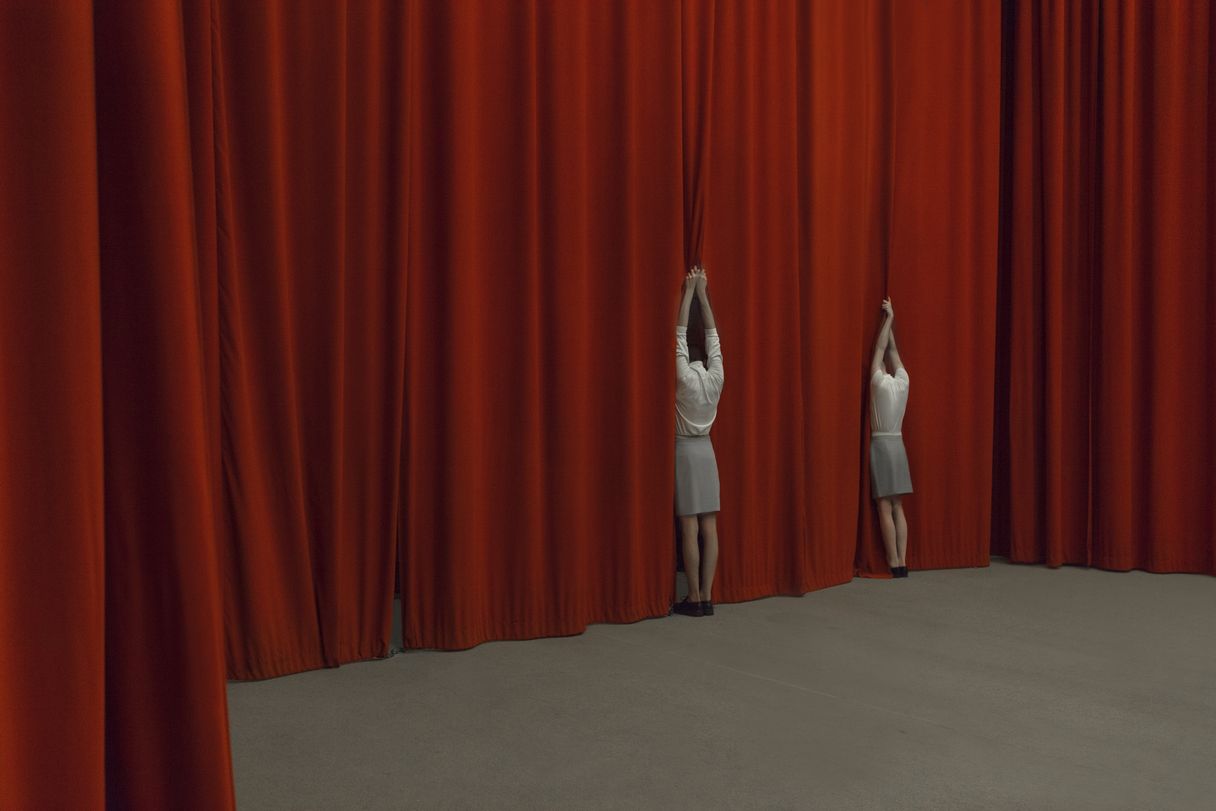

Evelyn Bencicova & Adam Csoka Keller, ASYMPTOTE

Evelyn Bencicova & Adam Csoka Keller, ASYMPTOTE

In the elegant and almost clinical images produced by Evelyn Bencicova and Adam Csoka Keller, anonymous models pose next to buildings from the socialist period of Slovakia. Their forms seem to merge into the powerful architecture, suggesting that bodies function as pillars for institutional constructions and for an ideology that raised much hope but eventually failed. The work also suggests that to a young generation often described as ‘individualist’, the aesthetic of collective participation must have a very seductive, if abstract, appeal…

Opening of the exhibition. Photo Foto: eSeL – Joanna Pianka for Q21

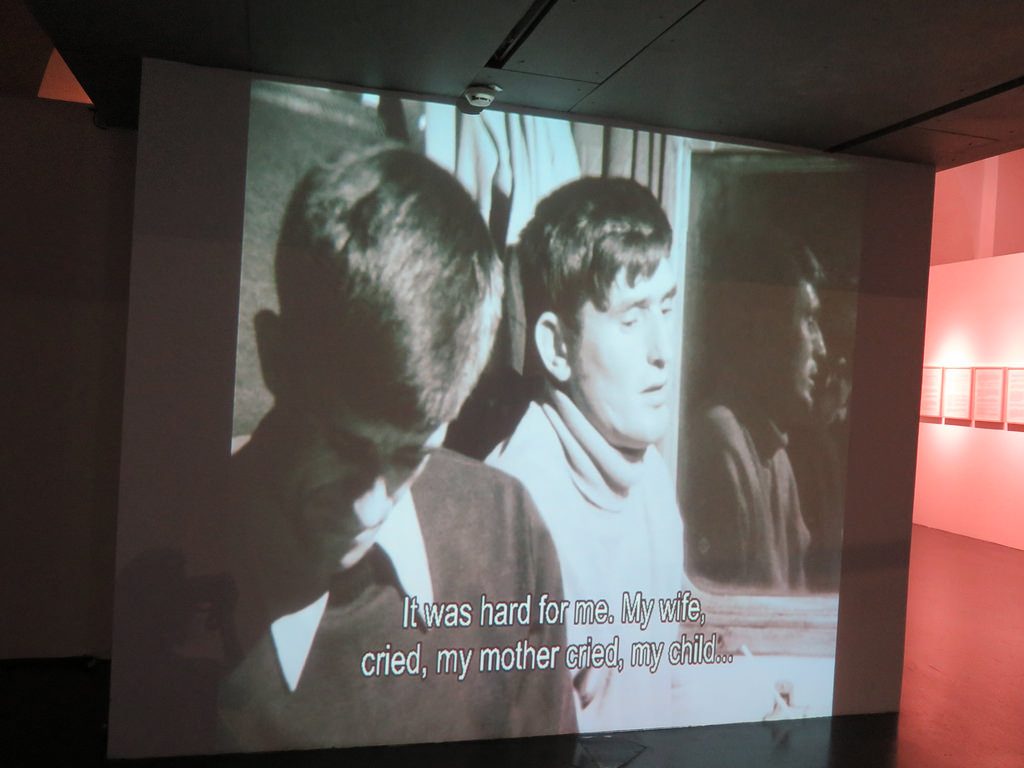

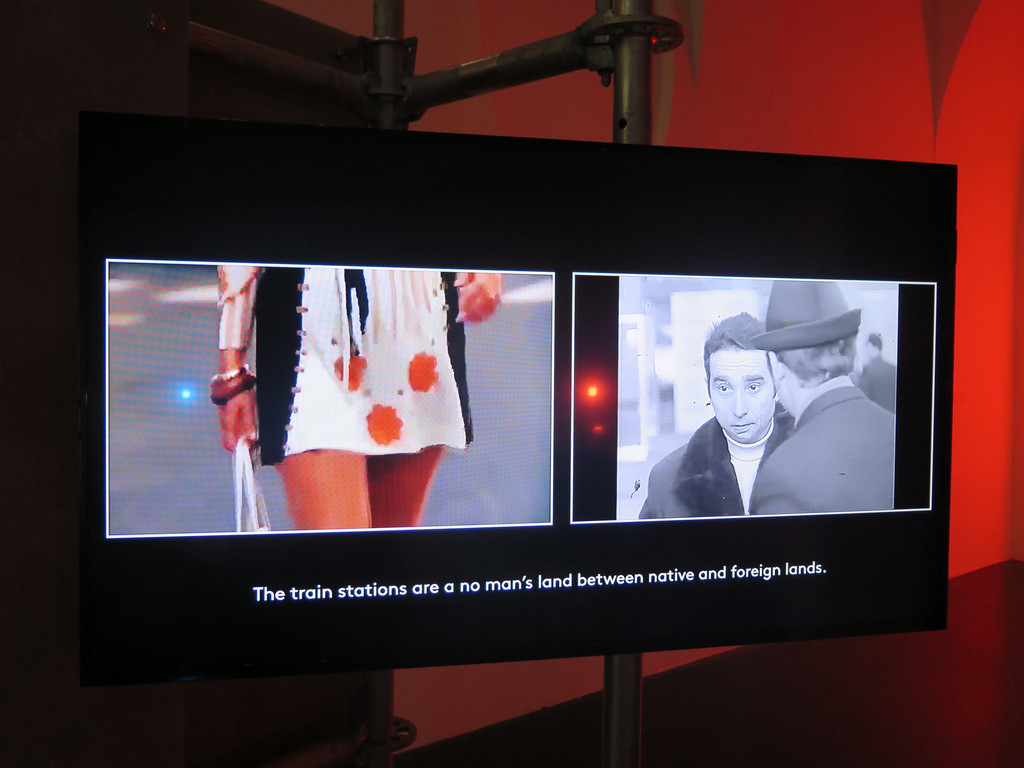

Krsto Papićs, The Special Trains (film still), 1971

Krsto Papićs, The Special Trains (film still), 1971

Krsto Papićs, The Special Trains, 1971

Krsto Papićs’ The Special Trains is an extremely moving documentary.

It shows how the men who had volunteered to emigrate to Austria or Germany are transported by “special trains.” They are accompanied by a guide who ensures that they will arrive at their final destination quietly and cause as little disorder as possible. Prior to their trip, the workers are submitted to medical inspections to make sure that they will be strong and healthy enough to get a worker permit.

The film maker interviewed a group of these Yugoslavian guestworkers on the train. Many of them had to leave their family behind and most are a bit dispirited, wondering if they had made the right choice, realizing how hard it will be not to see their children, fearing that they will be regarded as second class citizens, lamenting the fact that they will feel uncomfortable in a country they know so little of. The film follows their arrival at Munich main station, where they are led to a basement. From this point on, they are no longer called by their names but by numbers.

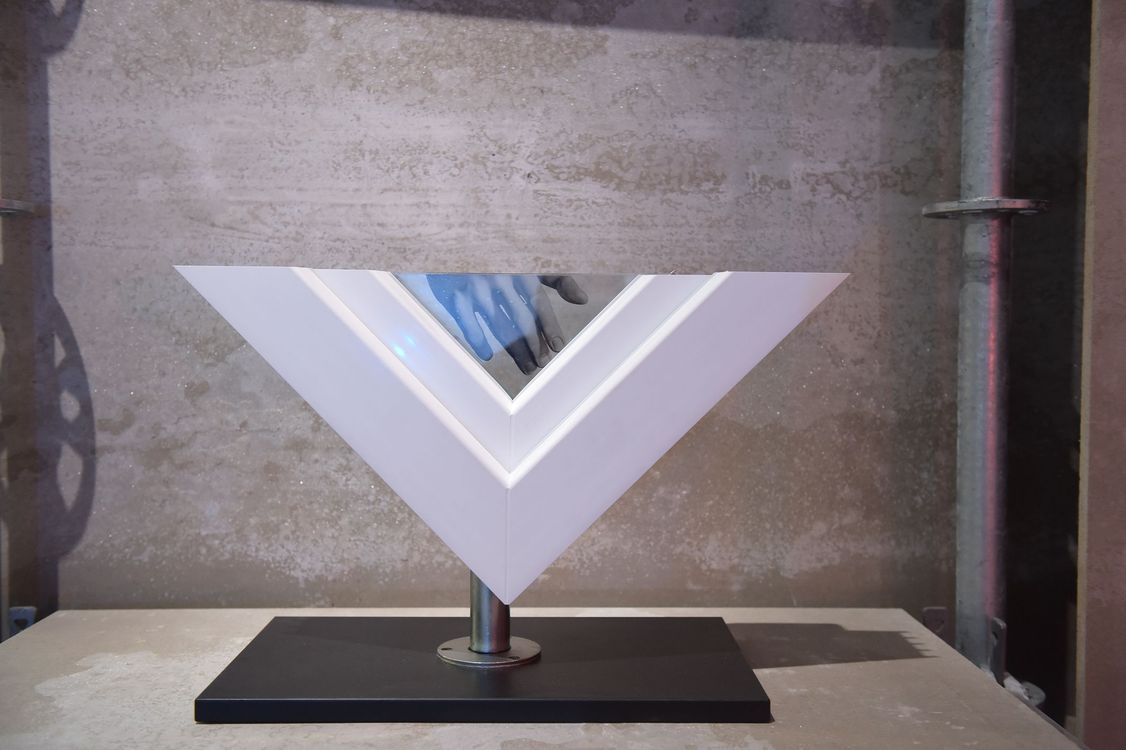

Bernd Oppl, Crooked Building, 2015

Bernd Oppl distorted sculpture of a social housing block in Vienna highlights the inherent instability of such spaces. The Crooked Building also reminds visitors that while the guestworkers actually built the structures, they received quite late (compared to other countries) the right to get access to social housing.

Nikola Knezevic, V for Vienna (cropped window), 2016. Photo: Joanna Pianka

Nikola Knezevic. Installation view frei_raum Q21 exhibition space. Photo: Q21

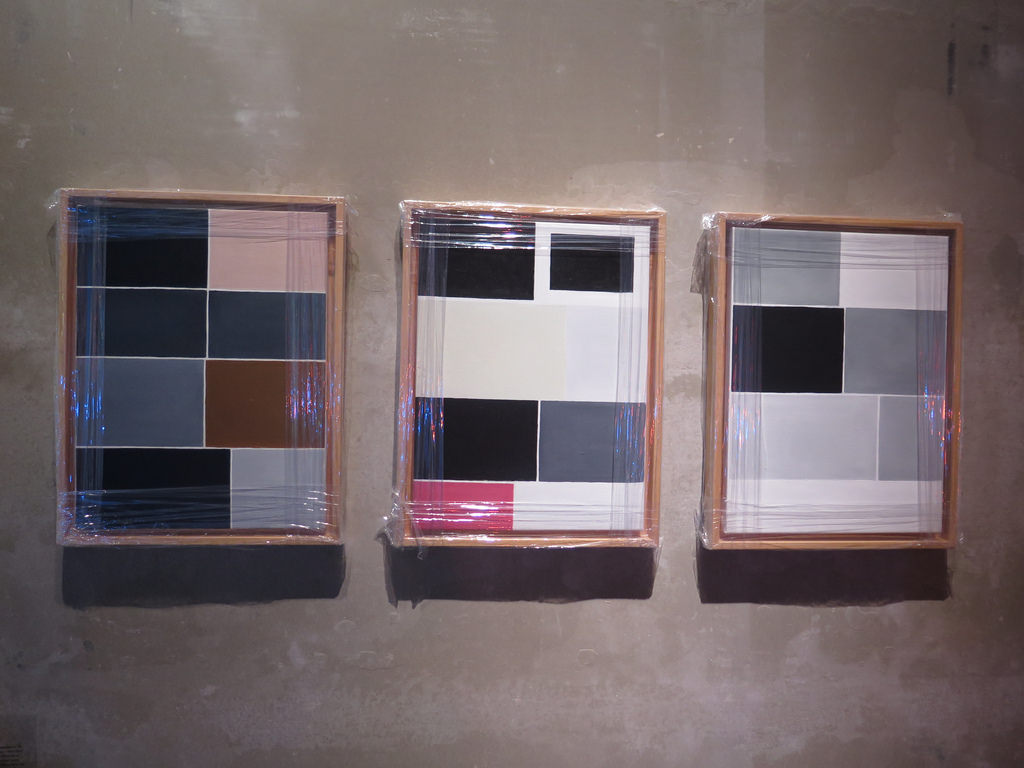

Nikola Knezevic, The Placeholders (three oil paintings), 2016

Nikola Knežević‘s tryptich was another stand-out for me.

V for Vienna (cropped window) is a trophy to a guestworker employed in an aluminum factory in Vienna. Part of his job involved making each of the aluminum windows and doors for the Hilton Hotel in Vienna. The worker feels proud each time he now walks by the hotel.

The Placeholders are Mondrian-style paintings that allude to the presence of the phenomenon of guestworkers on the largest contemporary archive in the world: the Internet. Knezevic did an image search for the word Gastarbeiter and encountered mostly black and white images. Before the images appear on the screen, they are represented by placeholder filled with the dominant colour of each image. The placeholders that emerged while googling Gastarbeiter were sent to an oil painting company in China, where they were turned into abstract paintings and shipped back to Vienna. Everything was commissioned, executed and paid from a distance. The workforce is no longer required to be mobile as it was in the 1960s.

Nikola Knezevic, Not Yet Titled, 2016

The final work in the series, Not Yet Titled, brings side by side an ORF documentary from the 1970s about guestworkers and the opening sequence of Orson Welles’ film F for Fake (1974.) Both films use the same editing technique, the former to depict guestworkers, and the latter to introduce a professional art forger.

In each case, the camera follows a young woman in miniskirt walking in the street while male passersby (unaware that they are being filmed) stop on their track and openly stare at her. The woman in the ORF report is presented as an objectified and slightly threatened victim, while the one in Welles’ movie (who in real life was a Croatian woman living in Vienna), as a powerful temptress who directs men’s desire. The voice over of the ORF film even deplores that the guestworkers came with very few women.

The juxtaposition shows how similar images can be manipulated and given a different interpretation depending on the message that has to be communicated.

Olga Dimitrijevic. Photo Joanna Pianka for Q21

Olga Dimitrijević set up a “celebratory karaoke bar,” where visitors are invited to perform songs based on the lives and favourite songs of ex-Yugoslav women who live and work in Vienna.

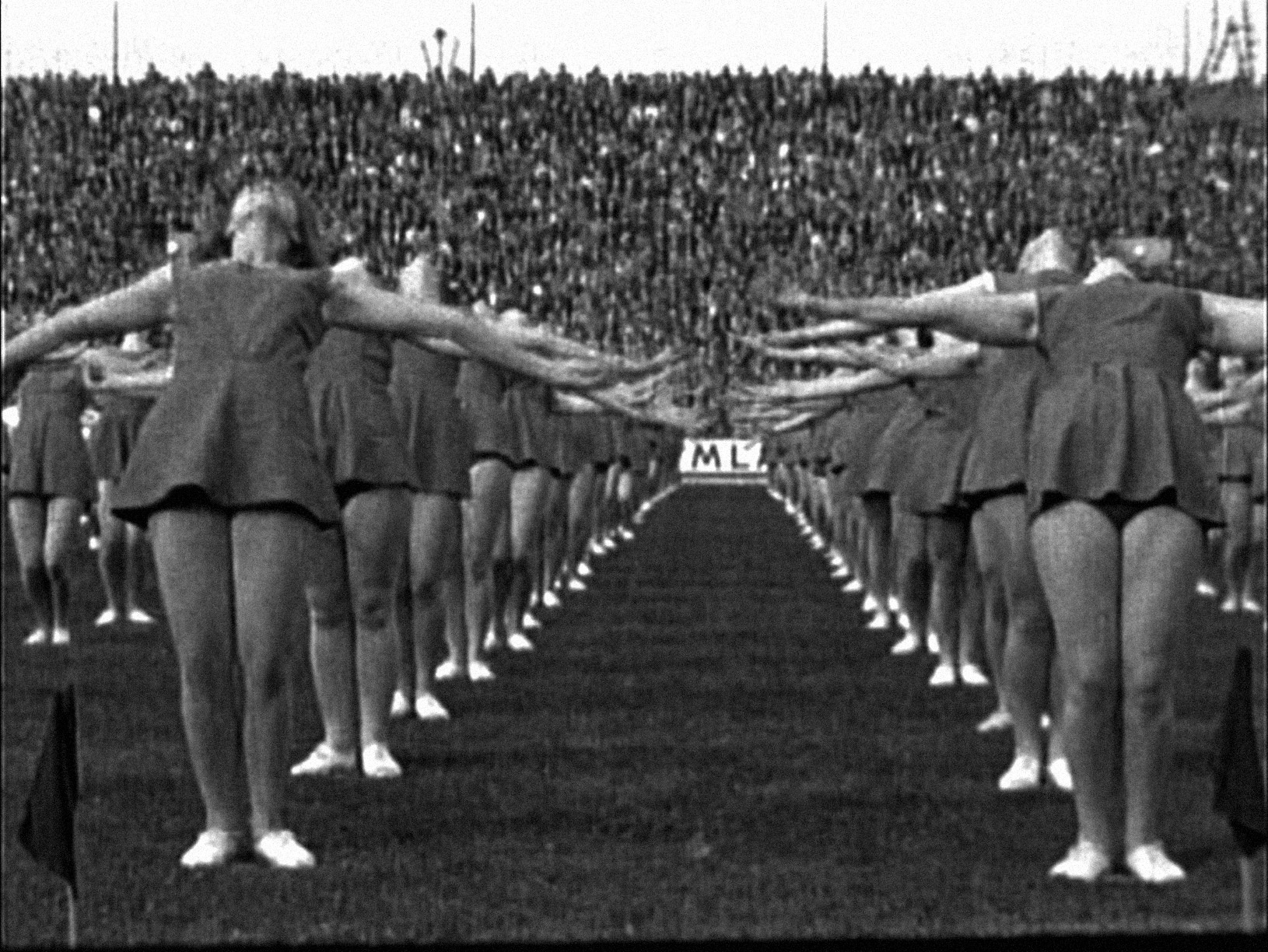

Marta Popivoda, Yugoslavia, How Ideology Moved our Collective Body (still from the film), 2013

Marta Popivoda, Yugoslavia, How Ideology Moved our Collective Body (trailer), 2013

Marta Popivoda, Yugoslavia, How Ideology Moved our Collective Body (still from the film), 2013

In the center of the exhibition is a monumental projection of Marta Popivoda’s film study on “Yugoslavia: How Ideology Moved Our Collective Body (2013)”. The film uses archive footage to draw a personal perspective on the history of socialist Yugoslavia and its tragic end. The footage focuses on state performances (such as May Day parades and Youth Day celebrations) and on counter-demonstrations (student and civic demonstrations in the ‘90s, and the so-called Bulldozer Revolution which overthrew Slobodan Milošević in 2000.) Ultimately, the archive images demonstrate how ideology has the power to shape performances of crowds of people operating as one, but it also exposes the power of the same crowds to destroy the ideology.

More images from the exhibition:

Marko Lulic, für ein Denkmal für Migration in Perusic. Photo: Joanna Pianka

Josip Novosel, U Can Sit With Us. Photo: Bernd Oppl

Leyla Cardenas, Overlaying. Photo: Bernd Oppl

Claudia Maté, Untitled

Opening of the exhibition. Photo Foto: eSeL – Joanna Pianka for Q21

Opening of the exhibition. Photo Foto: eSeL – Joanna Pianka for Q21

Opening of the exhibition. Photo Foto: eSeL – Joanna Pianka for Q21

If you speak german, then well done you! You can enjoy this interview that Vice did with curator and artist Bogomir Doringer. Otherwise, i’d recommend the lively audio guide tour with the curator.

AJNHAJTCLUB was curated by Bogomir Doringer. The show remains open at the frei_raum Q21 exhibition space, MuseumsQuartier in Vienna until 4 September 2016.