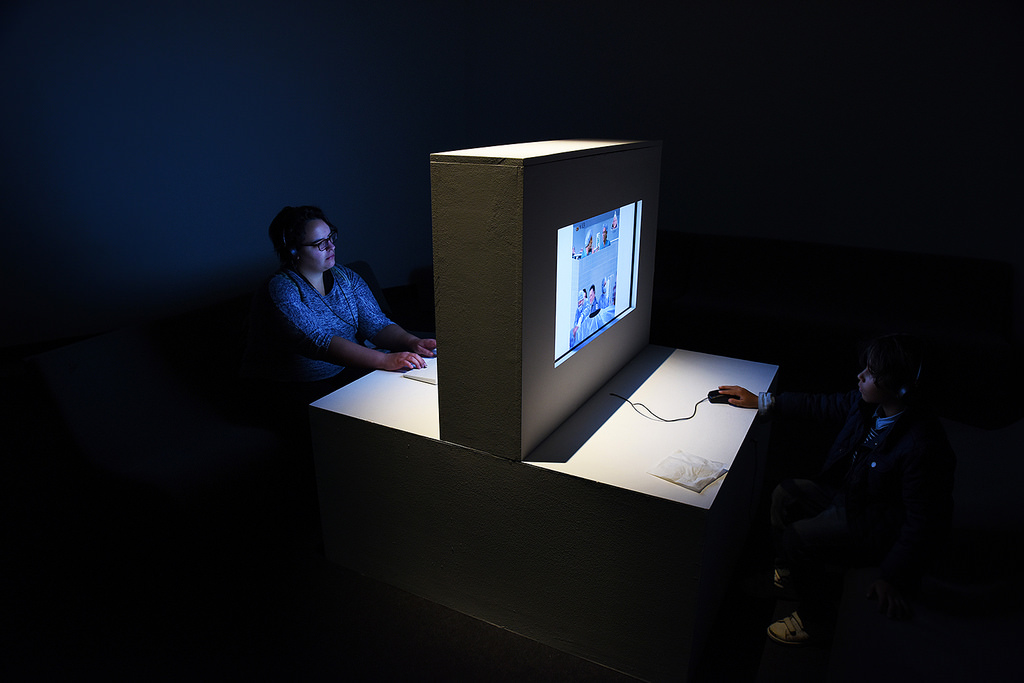

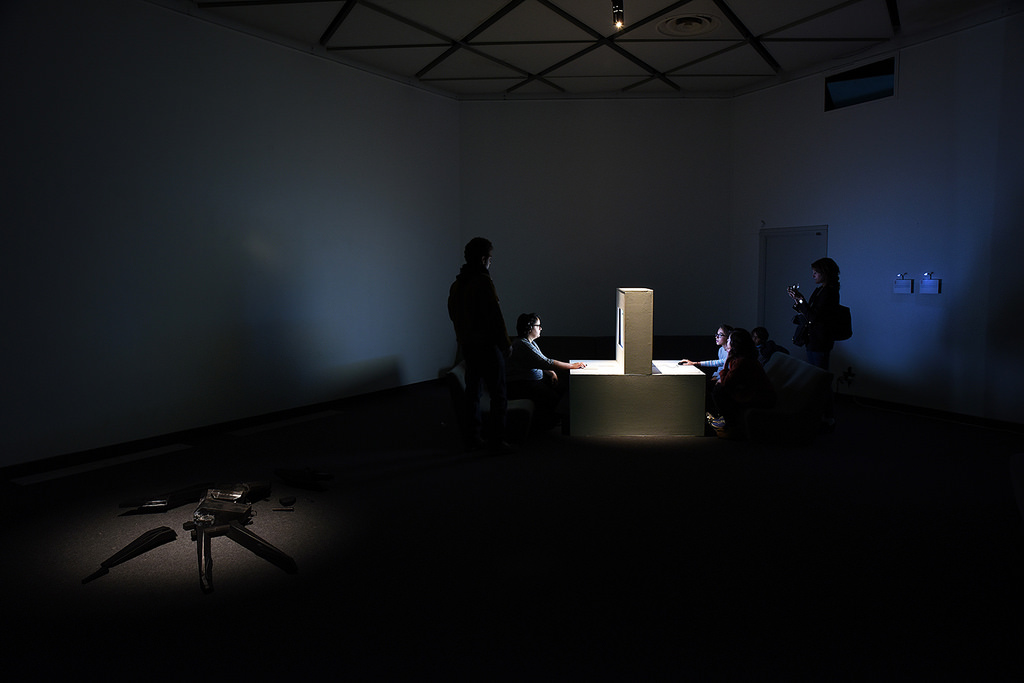

Pippin Barr, Let’s play : the Shining and The junior mint. Photo Luce Moreau for GAMERZ

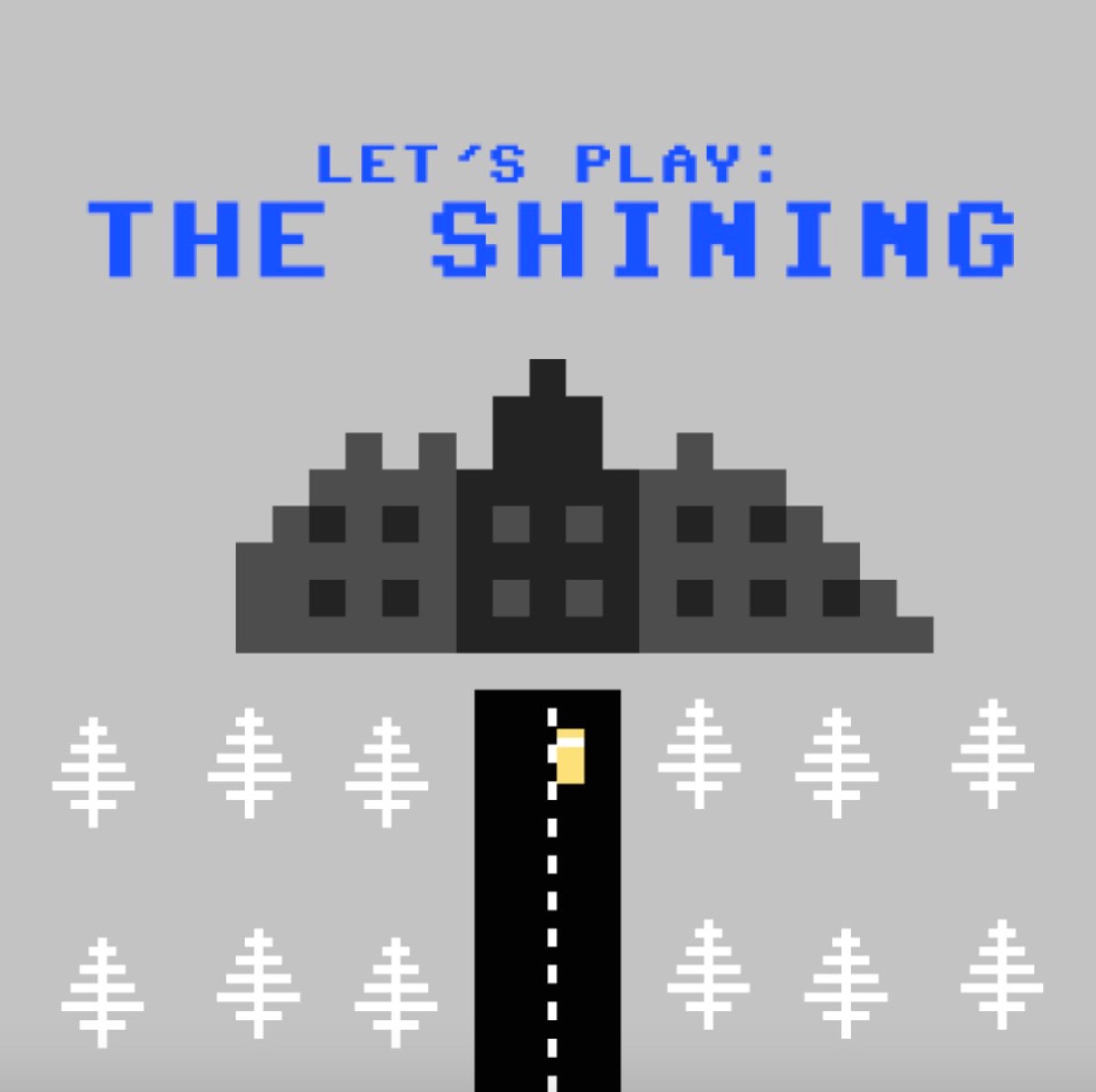

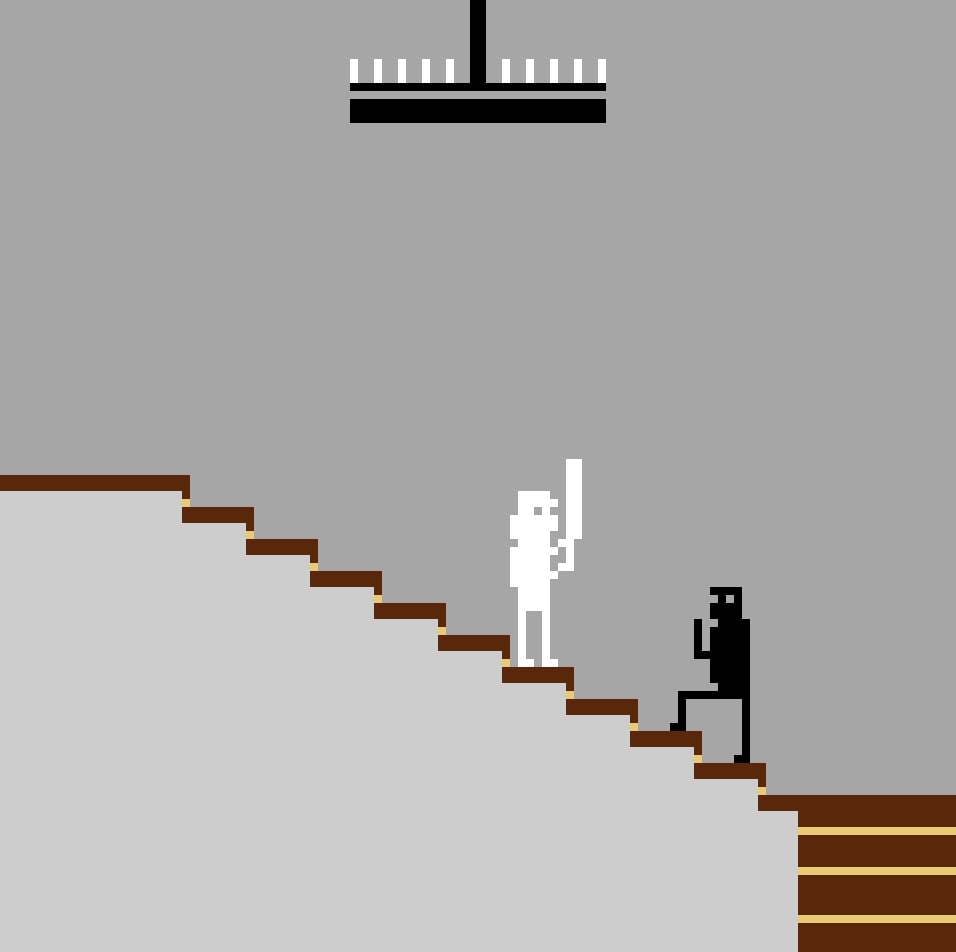

Pippin Barr, Let’s play : the Shining

In his influential 1938 book Homo Ludens, cultural theorist Johan Huizinga argued that play is an essential condition to the development of cultures. This year’s edition of GAMERZ in Aix en Provence not only demonstrated that there is indeed nothing trivial about play but the event also explored how our relationship to play has changed with the advances of technology. And, more interestingly, it invited visitors to join artists whose work investigates how the digital age is changing man, whether we’re talking about Huizinga’s homo ludens, the working man (Homo Faber) or more generally the modern man (Homo sapiens.)

With this premise, the festival could either have dived into the amusement arcade extravaganza with an arty pretense or taken the dry and austere road of turning play into a series of humourless exhibits relying on deep theory (don’t look at me like that, the French are really good at organizing this type of hyper analytical events.) GAMERZ combined the best of both worlds with a series of performances, discussions and an exhibition that could clearly be enjoyed by the most art-phobic but that also critically investigated how the dialectic, gestures, dynamics and instruments of gaming have infiltrated many aspects of our life. From education to art, from fashion to warfare, from language to advertising, etc.

One of the interesting phenomenons about game is that techniques and experiments that were pioneered by artists, users and hackers feed into the R&D labs. And vice-versa, with innovations about interfaces, control systems and interactions bouncing back and forth between these two worlds and eventually seeping into mainstream consumption and culture.

As curator Quentin Destieu writes in his introductory essay for the festival:

These new interfaces are available for everyone, and have inspired new generations of artists who use these mass technologies with fun and spontaneity. The artists are therefore involved in creating the “Digital homo ludens”, a new human species that turns these products into creation tools.

There was a lot to like and blog about in this 11th edition of GAMERZ. I’ll start by focusing on the artworks that focus more literally on this theme of the digital homo ludens: the video games, many of which you will be able to play online by clicking on the links i’ve provided below:

Pippin Barr, Let’s play : the Shining and The junior mint. Photo Luce Moreau for GAMERZ

Pippin Barr, Let’s play : the Shining

Pippin Barr at Festival GAMERZ 11

Pippin Barr was THE discovery of the festival for me. Let’s Play: The Shining is a game adaptation of Stanley Kubrick’s movie of the same name. The film is broken down into its most iconic scenes: the carpeted corridors that lead the tricycle to the creepy twins, Jack hacking through the door with an axe, the blood elevator, the hedge maze, etc

The graphic and animations are retro Atari-style but the feeling of uneasiness that characterizes the film remains. You’ve got to play the game to understand how brilliant it is.

The other Barr work shown at the festival was The Junior Mint, it’s an homage to Seinfeld and i won’t write anything and pretend i get all its wittiness because i’ve never seen that tv series. You can play it by clicking over here. As for me, i’m partial to a bit of curse from the Olympian gods so i’ll just go back to playing Ancient Greek Punishment. It wasn’t presented at GAMERZ but i discovered it while clicking around the website of this brilliant artist.

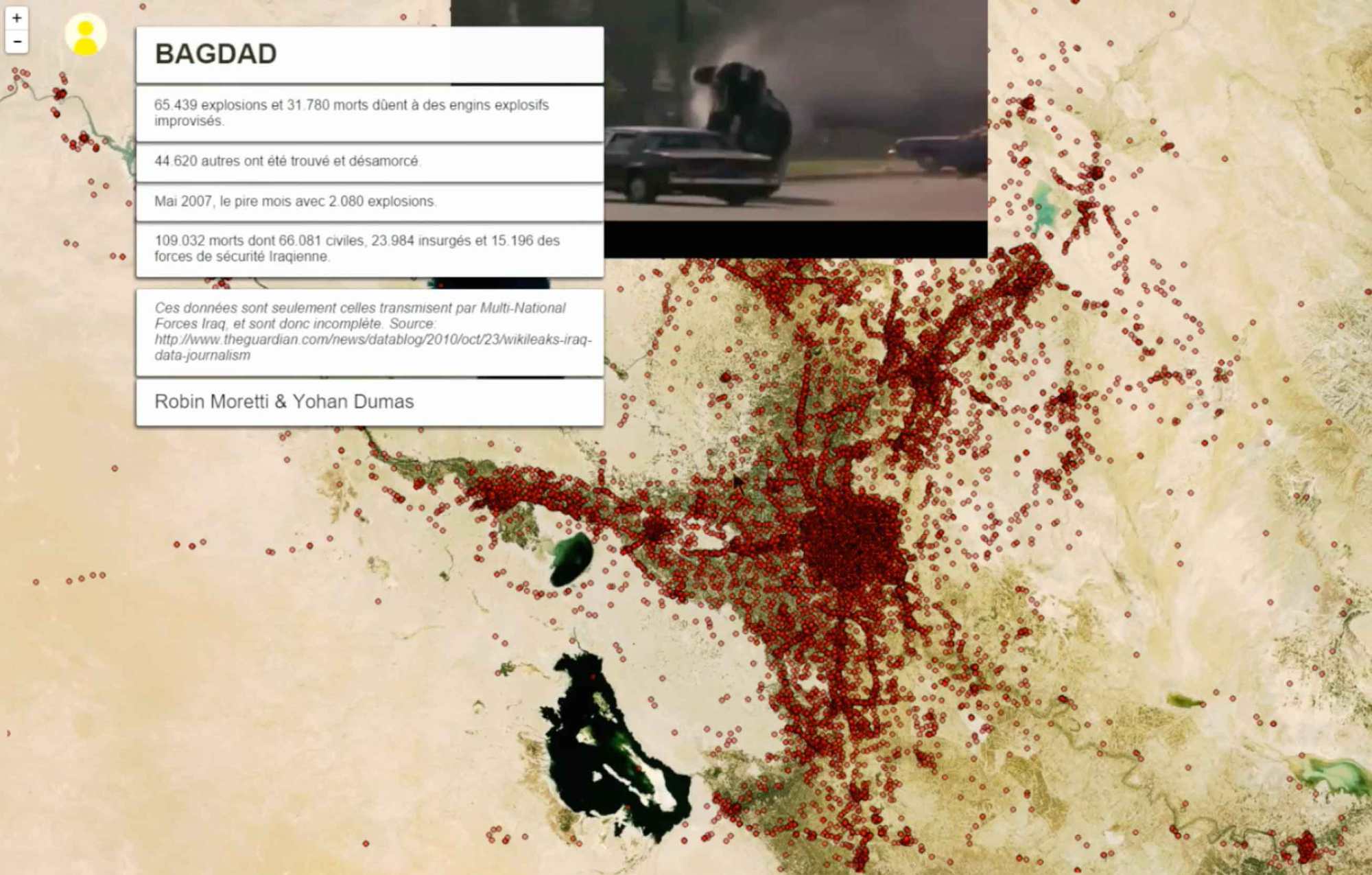

Robin Moretti and Yohan Dumas, Blockbuster, 2015

Blockbuster combines data journalism and Hollywood cinema to examine the conflict in Iraq. The artwork used data found on Wikileaks Iraq to chart on a Google map the improvised explosive devices that blew up in the country since 2004. Each explosion is marked by a little red dot. When you click on one of those red dots, a video of explosion from a movie is played.

The title of the piece goes back to the original meaning of the word blockbuster. A blockbuster bomb was one of the largest bombs used in WWII by the United Kingdom’s Royal Air Force and the explosive power of its blast was such that it could destroy an entire street or large building.

The project attempts to open up journalistic data to the broad public, in a ludic yet critical way that questions media representation of conflicts and individual perception of war.

Molleindustria and Jim Munroe, Unmanned, 2012

Molleindustria and Jim Munroe, Unmanned, 2012. Photo Luce Moreau for GAMERZ

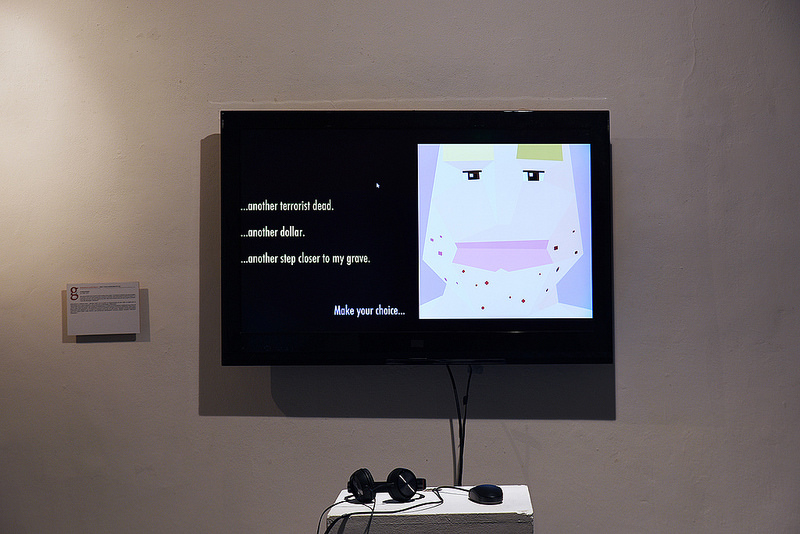

The Unmanned video game puts you in the boots of an UAV pilot. Which is rather ironic considering that drone warfare has often been compared to video game playing. The soldier sits behind a screen, pressing buttons, shooting targets and generally not being taken very seriously. Yet piloting drones comes with its own responsibilities and traumas.

Your character is a father, a husband and a drone pilot with a seemingly unspectacular life. During the day you participate to UAV attacks. In the evening, you go back home to your suburban life. Throughout the game sessions, you collect medals for rather absurd “achievements” (well, in theory because i never managed to get even one medal.) You get rewarded when you don’t shed blood while shaving, for example. On the other hand, if you’re working and shoot without authorization a target wearing a turban, your only punition is to fill in forms.

Unmanned reveals the conflicts that rage inside a pilot’s mind. How is it possible to dissociate your professional life from your private one? A dilemma particularly discernible when the soldier is at home, playing first-person shooter games with his son. How does finding yourself so far away from the battlefield affect the life of the people around you? Who do you share your concerns and trauma with when even your own family doesn’t value what you’re doing for a living?

Unmanned was written by science fiction author Jim Munroe and politically-engaged game studio Molleindustria.

Bastien Vacherand, Syndrome de la turret, 2015. Photo Luce Moreau for GAMERZ

The installation Syndrome de la turret consists of a 3D-printed automatic machine gun from the Half-Life 2 video game and a CCTV screen where the visitor virtually triggers his own death. The system detects your presence as you enter the room, turns it into an on-screen character and automatically kills it with a machine gun.

As for the sculpture, it counts 54 different parts that were printed using a small desktop 3D printer and then assembled and glued to form the full scale model. The size of the physical weapon reflects the one in the game. It is therefore 1.65 m high. When the artist installed it in the exhibition space, it stood there for a couple of minutes and then it just crumbled. The artist decided to leave it as it was, with bits and pieces scattered across the floor. The broken machine gun reflects the tensions inherent to the video game medium but also the fact that any object found in video game has its own logic and respond to other laws of physics than the ones that govern our tangible world.

Turret Syndrome proposes to bypass the video game space and the opportunity of a virtual tour by restraining interaction to a simple triggering action with a violent and baneful ending.

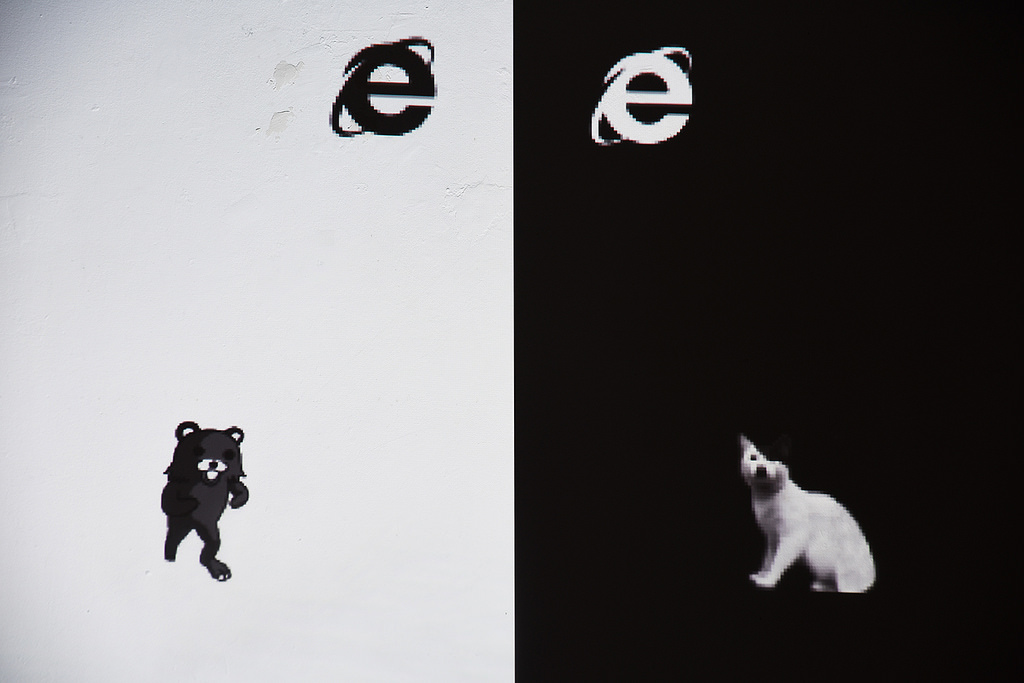

Labomedia, La Course de cri pédo-nazi

The premise of La Course de cri pédo-nazi (Paedo-nazi shouting race) made me laugh out loud: Internet is only used by two kinds of people – paedophiles and Nazis. To play, you pick up your cute but ambiguous side: team Kitler or team Pedobear and shout as stridently as you can to prove that you hold the truth and conquer the Internet.

Above the characters is the Microsoft Internet logo as it appeared on every Windows Desk in the late nineties, a time when it became so widely used it put other web browsers such as Netscape put out of business. As the artists wittily note: Not to mention that Microsoft had the brilliant idea to name its web browser “Internet Explorer”. If you cannot make the difference between the Web and the Internet, now you know who is to be blamed.

Dolls in the Kitchen, culinary performance for the opening night of GAMERZ. Photos Luce Moreau for GAMERZ

My photos are here. And these are the ones made by Luce Moreau, the festival photographer.

![7 art and tech ideas I discovered at Meta.Morf 2024 – [up]Loaded Bodies 7 art and tech ideas I discovered at Meta.Morf 2024 – [up]Loaded Bodies](https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/53705969154_73dfdfea6f_c-300x200.jpeg)