Robert Capa, Just after the liberation of the town, a French woman who had a baby with a German soldier was punished by having her head shaved, Chartres, France, 18 August 1944

Carl Mydans, A tondue, 1944

I’ll never forget the stories my grandmother used to tell me about the ‘shaved women of the Libération. After the Second World War, women accused of having worked with the nazi invader, spied for them, denounced their neighbours, and participated to nazi operations were paraded in the street, insulted, spat on, beaten, etc. The apotheosis of this public humiliation was the moment when men (they were usually men) would shave the head of the women as a punishment for being a ‘traitress’. Roughly 20 000 women were shaved in France in 1944-1945.

However, the only crime committed by some of these women was horizontal collaboration. They had slept with a German out of love, conviction, necessity, under duress or simply because they were prostitutes. All of them lost their hair, symbol of seduction and perdition. Of course, men were punished for colluding with the German invader as well but only women were stigmatized and punished for ‘sleeping with the enemy’.

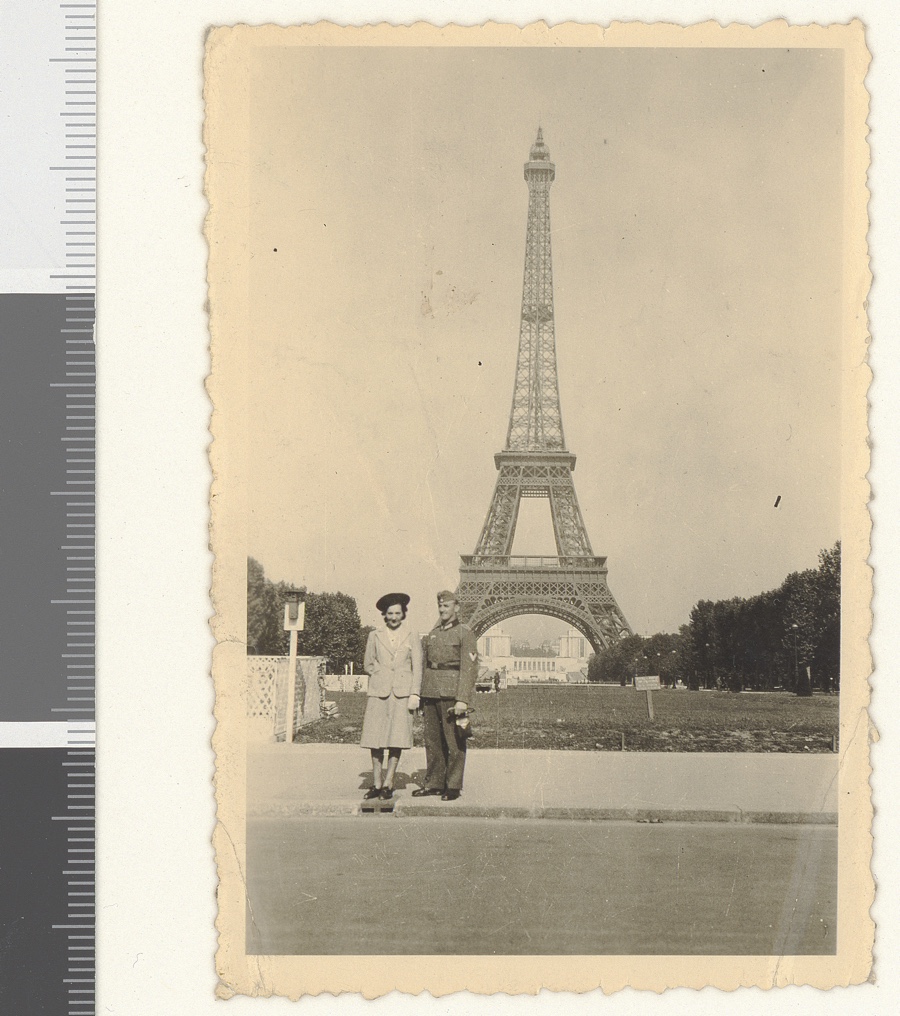

Album-souvenir d’Isabelle H. (Paris, trips in Normandy and on the French Riviera in the company of a German officer), 1944. Arch. nat. Z/6/1236

Album-souvenir d’Isabelle Hyer. Paris, trips in Normandy and on the French Riviera, 1944. (© Archives nationales)

Young woman and German soldier in Paris, investigation file of Marguerite P. Arch. nat., Z/6/123/1176

Women shaved and paraded on a truck in Cherbourg, 1945

Presumed Guilty, an exhibition at the Archives Nationales in Paris, explores how women have been judged according to different sets of values -and often with less impartiality- than men. From the XIVth Century to the end of the Second World War, French women were ‘presumed guilty’. They were judged for their crimes (or what was perceived as such) but also simply for being women. Something pertaining to their gender made them more likely to commit certain types of crimes. Until 1946, these women were interrogated by men, judged by men and condemned by them.

The exhibition examines this position through five archetypes of female felons: the witch, the poisoner, the child-killer, the rebel arsonist, and the traitor.

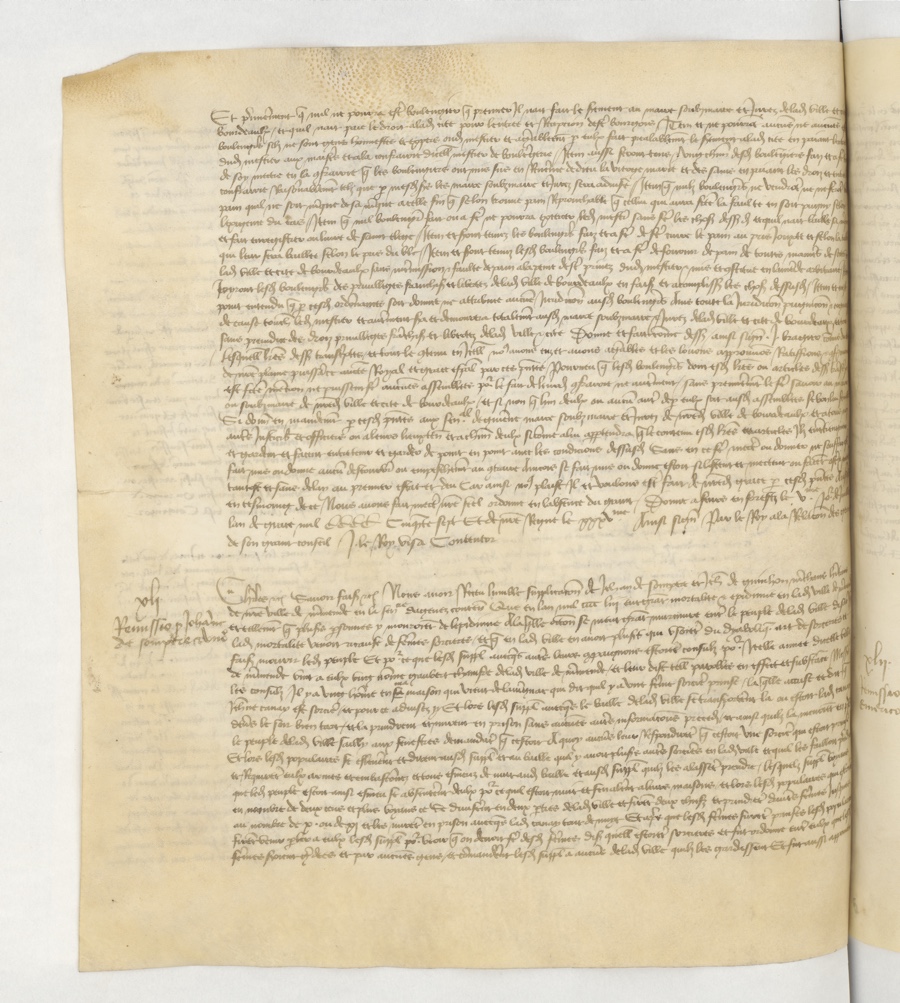

Between the XVth and the XVIIIth Century, 110 000 trials for witchcraft were held throughout France. 80 % of the accused were women. Women were regarded as weaker than men and thus more susceptible to be seduced and perverted by the devil.

It was believed that the devil would touch the woman and leave a mark on her body when they made their pact. The mark was supposed to be insensitive to pain. The investigators would thus meticulously examine the naked body of the accused woman and then prick their body with a blade. If the woman did not flinch nor bleed, it was a proof that they were a witch. Women were also asked questions about their sexuality, in particular the details of their copulation with the devil.

Violette Nozière who poisoned her parents

Violette Nozière during her trial in Paris in 1934. Photo credit: Rene Dazy, Rue des Archives, Paris, France

In the modern era, the figure of the witch with her potions and knowledge of herbs was replaced by the one of the female poisoner. Poison was seen as the woman’s weapon of choice. “Brave” men kill with a knife. Cowardly women with drugs. Poisoning someone was adjudged to be more shocking than homicide: it suggested premeditation, ruse and hypocrisy and therefore merited greater punishment. Furthermore, the crime indicated a woman who had chosen to depart from her traditional role of a ‘nurturer’.

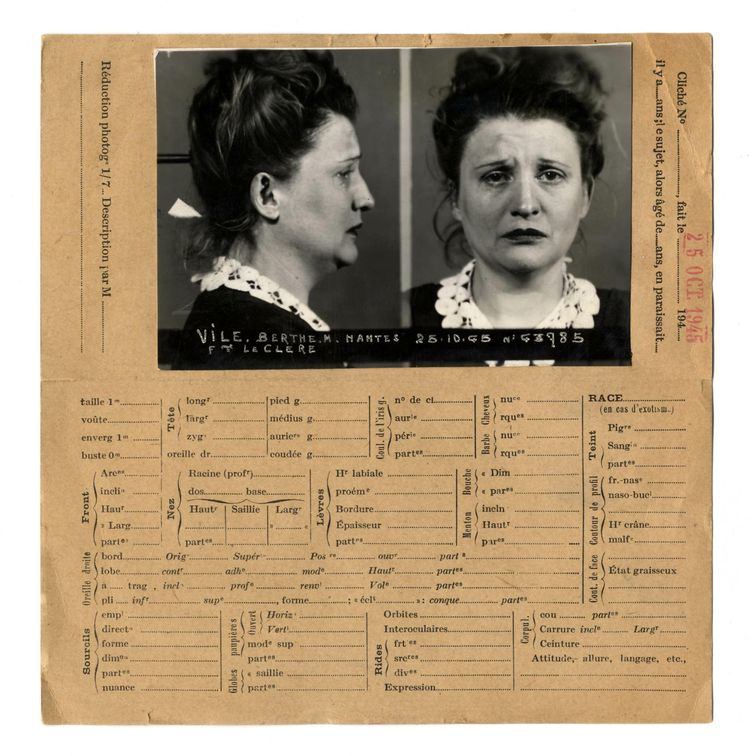

Berthe V., arrested for child killing. Archives départementales de Loire-Atlantique

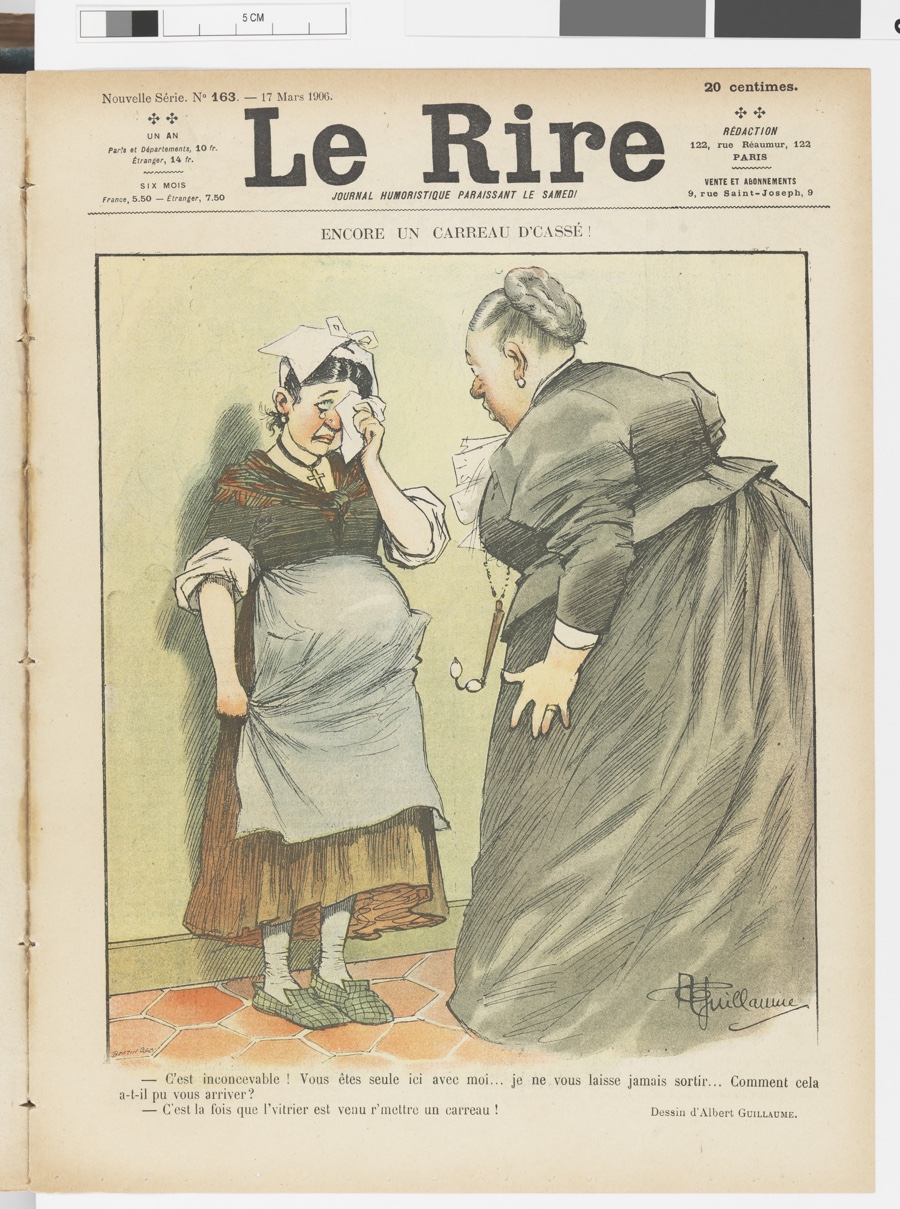

Encore un carreau d’cassé (young pregnant maid and her boss), published in Le Rire, 12th year, 1905-1906. Arch. nat., AE/II/3734

A fourth figure of criminal is the child-killer. These were often girls who had only a vague understanding of what their body was going through and were afraid of losing their ‘reputation’ and thus any chance of ever finding a good husband. Some had been raped, victims of incest or just naive. During the trials, the judges often interrogated them about the seduction and intercourse that led to an undesired childbearing.

Justice was harsh to these women. At least until the XIXth century when society finally recognized that men had to bear some responsibility for the shame, misery and despair of these women.

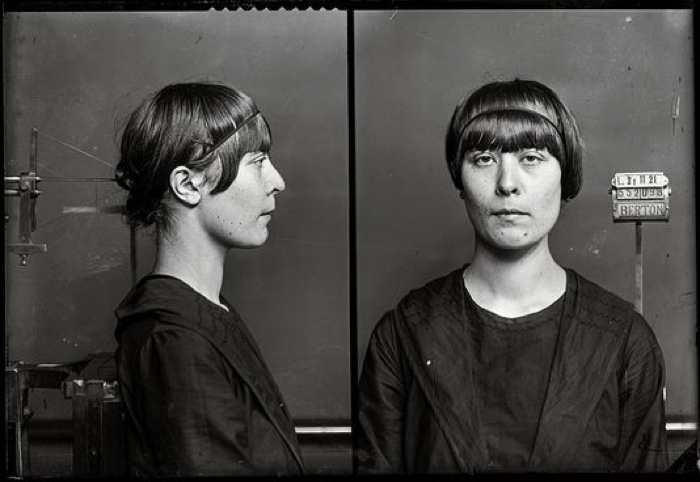

The anarchist Germaine Berton, 1921

Then came the pétroleuses, the women accused to have used bottles full of petroleum or paraffin (similar to modern-day Molotov cocktails) to set on fire key buildings in Paris during the radical socialist and revolutionary government that briefly ruled the French capital in 1871. Many government buildings were indeed set afire by the soldiers of the Commune but it was only only the rumour that attributed the arson to women. Hundreds of pétroleuses (a word that has no equivalent for men) were brought before a court, none were recognized guilty of intentional firing. But the myth perdured and the term was applied to rebellious women who didn’t conform to the rules that govern their gender and whose beliefs and gestures couldn’t be controlled by men.

Germaine Berton, for example, was born long after the Commune but she was seen as a marginal, a kind of pétroleuse. Berton was a young anarchist activist who shot one of the leaders of the French Far Right organization known as Action française. She was arrested and claimed responsibility for the crime. Everything about her belied the ideal of a woman: she had political opinions, she acted alone, was single and wore short hair. On 24th December 1923, the tribunal found her not guilty of the crime. The judges didn’t want to turn her into a martyr so they claimed she couldn’t be held responsible for her act.

Unfortunately, Presumed Guilty closes today. It is a fascinating exhibition. 320 interrogation records and previously unseen documents give their voice back to these women.

The exhibition closes at the end of the Second World War but as we all know (glass ceiling and all that), the fight for equality, dignity and recognition is not over for many women across the world.

On a side note, i was very surprised to see how few men were visiting the exhibition on the day i was there. There were dozens of women of all ages but only one ‘husband’.

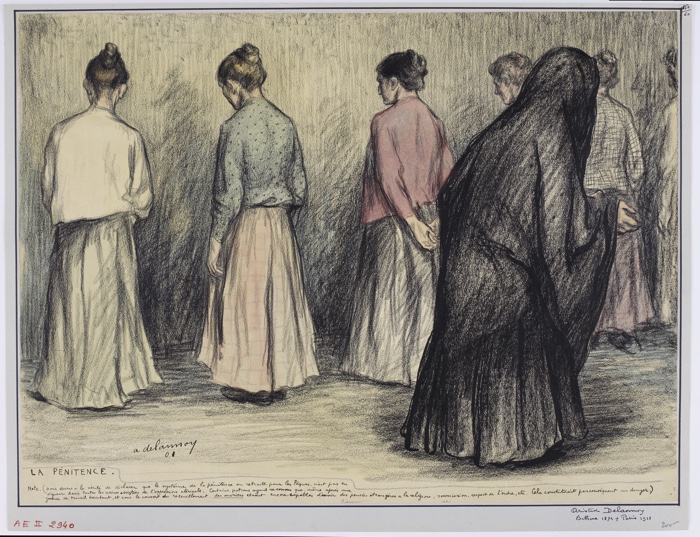

Workers monitored by a nun, drawing by Aristide Delannoy, L’Assiette au beurre, 1901. Arch. nat. AE/11/2940

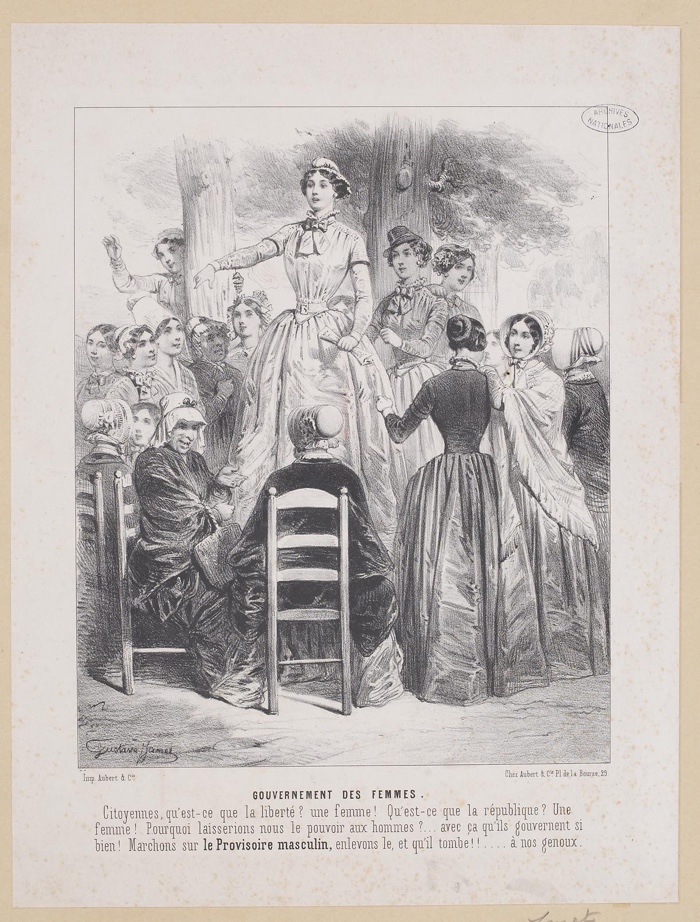

Gustave Jamet, Women’s government, 1848. Arch. nat., AE/II/3513

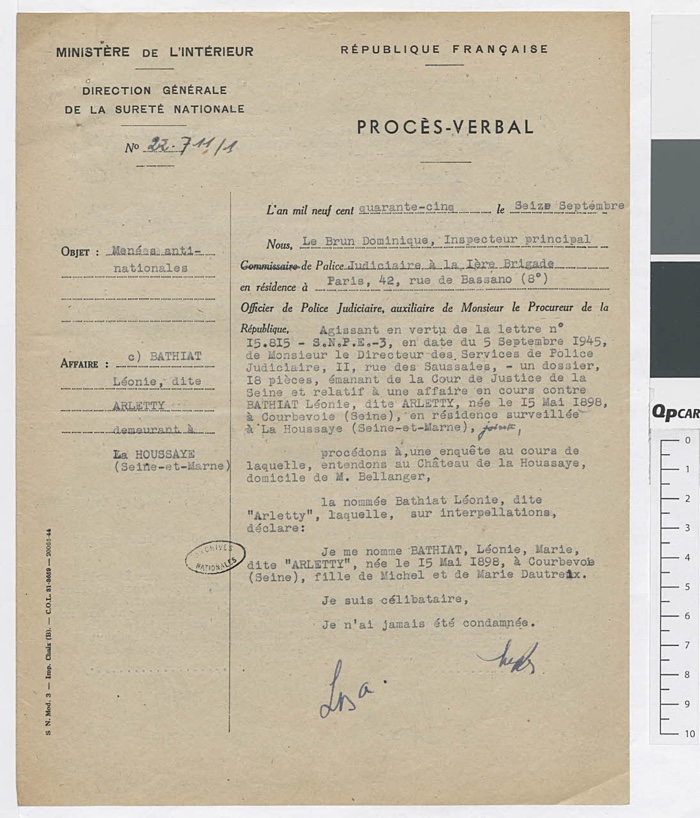

Police report about Léonie Bathiat, better known as Arletty, Paris, 3 October 1945. Arch. nat., Z/6SN/105, dossier 40863

Letter of remission from 1457 for the execution in Marmande of several women accused of witchcraft. Arch. nat., JJ//187, fol. 22 v°

Presumed guilty 14th-20th century is at the Hôtel de Soubise, Archives Nationales in Paris unil 27 March 2017.

Image on the homepage found over here.