A Visual Weapon. Soviet Photomontages 1917-1953 is a fascinating exhibition currently running at Passage de Retz in Paris. The collection tried to demonstrate how the changing style of Russian photomontages reflects changes in the political system and daily life in the Soviet Union from the 1917 Revolution until Stalin’s death in 1953. It wasn’t that clear to me in the absence of any explanation in the gallery beyond the title of the works shown but it definitely brightened my Saturday in the French capital.

A Visual Weapon. Soviet Photomontages 1917-1953 is a fascinating exhibition currently running at Passage de Retz in Paris. The collection tried to demonstrate how the changing style of Russian photomontages reflects changes in the political system and daily life in the Soviet Union from the 1917 Revolution until Stalin’s death in 1953. It wasn’t that clear to me in the absence of any explanation in the gallery beyond the title of the works shown but it definitely brightened my Saturday in the French capital.

The exhibition is divided in three parts: photomontages by great Soviet artists from the 1920s and ’30s (Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitsky, Gustav Klutsis, Piotr Galadzev, Varvara Stepanova, etc.); anonymous photomontages used in schools and factories; and photomontages dating from World War II.

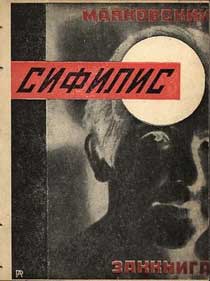

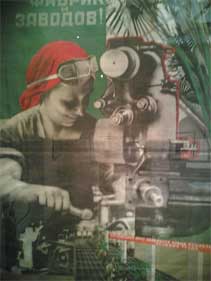

Alexandre Rodtchenko, Syphilis, 1926 and Sergey Yakovlevic Senkin – Green plants for the workshops of the factories, 1931

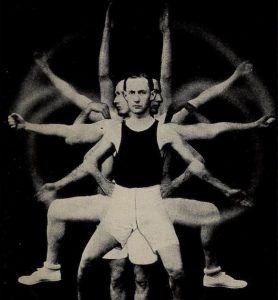

The photomontage technique appeared in Russia and Europe during WWI and bloomed particularly at the Bauhaus in Weimar and in Moscow. The pioneers of the genre are Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitsky and Gustav Klutsis. Their work gets a boost after the October Revolution. Vladimir Lenin declares that photography is a super-powerful propaganda tool in a country where 70% of the population cannot read. During the civil war he even plans to give every soldier a camera in order to let them use it as a weapon able to demonstrate visually and precisely the political changes. The idea wasn’t pushed any further. It was technically tricky and the country was facing more ruins and bleak desolation than the State would admit. The photomontage would then be used to portrait a cheerful “reality” and bright future. The medium was perfect: it combined the realism of the photography with the revolutionary rhetoric

B. Klinch, May 1 in Moscow, 1936

In the early ’30s the themes and structures of photomontage are gradually modified. The composition featuring several characters (workers, soldiers, farmers, etc.) are turned into a homogenous human aggregate dominated by a unique figure: Joseph Stalin.

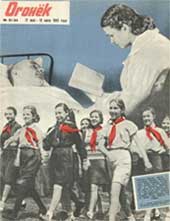

A.Jitomirski, Cover of the magazine “Ogonjok”, 1943 and Michael Dmitriev, On fire front, 1930s

During the WWII, the photomontage becomes the main propaganda weapon inside the country but also outside of it to demoralize the enemy. Jitomirski, for example, designed thousands of propaganda leaflets during the war. So many of them were thrown to German troops that Joseph Goebbels put the name of the artist on the list of the “Ennemies of the State” with a commentary that said “Find him and hang him!”

Because of the anti-cosmopolitan campaign, in 1949, many photographers lost the right to take any picture. And countless illustrated magazines had to close.

On view through January 7, 2007, at the Passage de Retz gallery in Paris.

My images on flickr. Mini-gallery on evene.fr and mdf.ru. Nice overview of the exhibition in Le Monde.

Image on top left corner: Soldiers of the Red Army by Varvana Stepanova, 1930.