Some 500 million animals are slaughtered every year for consumption in the Netherlands. The figures are even more horrifying if you look at the number of animals slaughtered for food every second. But while parts of these animals end up on your plate, they also generate a lot of ‘waste material’. Only a relatively small percentage of the cow blood for example will be dried and used in fertilizers. The remaining 70 percent will be simply disposed of.

Basse Stittgen, Blood Related, 2017-ongoing

Basse Stittgen, Blood Related, 2017-ongoing

Designer Basse Stittgen transforms these leftover of the meat industry into a dark, organic and versatile bioplastic. He uses the discarded body fluid as a biomaterial that he dries, heat-presses and then turns into a protein-based biopolymer from which he crafts small objects. Various pieces of dinnerware are direct reminders of the consumption of animals. Small egg holders that can be stacked into a totem that evokes the mystical sides of blood. A jewellery box invites us to question the value of blood, and perhaps also the value of animals after their death. The designer even created a record playing the heartbeat of a cow.

Basse Stittgen, Blood Related, 2017-ongoing

Basse Stittgen, Blood Related, 2017-ongoing

Most of us will have some kind of visceral reaction to the project. Smooth consumer goods made of solid blood feel a bit revolting and upsetting. The use of blood to create domestic goods forces us to confront the symbolic as well as the material dimension of a liquid we associate with both life and death. Furthermore, these Blood Related objects highlight the contradictions at the core of our relationship to animals. In theory, we all love animals. But not enough to stop buying the products of their exploitation. We know we need slaughterhouses but we prefer them to function far away from our sight and thoughts. Facilities where animals are butchered used to be located in urban centers but are now located outside city limits for “environmental and hygiene” concerns. The building of the ex-slaughterhouses have since been cleaned up to house swanky cultural centers.

The most interesting question this project asks is thus: Can this biomaterial ever become ‘just an object’, without any further associations?

Basse Stittgen‘s objects made with blood are currently part of ReShape. Mutating Systems, Bodies and Perspectives, an exhibition at MU in Eindhoven that explores theme of mutation and transformation. I took the show as an excuse to get in touch with the designer and ask him a few question about a project i found both curious and disturbing:

Hi Basse! How did you get the idea to create this rather surprising material? Is there in it any political or ethical comment on the meat industry? Or is it a more pragmatic solution to reduce industrial waste?

The project started as a broad research into bio materials and their history, at one moment I came across a french bio material created in 1855 called bois durci – it consisted of 80% sawdust and 20% oxblood. The possibility to make a solid material from blood sparked my fascination and I started doing first experiments.

There is no intention of a direct political comment on the meat industry, the objects are supposed to physicalize an invisible waste and connect the consumer again to the production of meat and asks to be aware of where meat comes from and what that takes. The project is not meant to be developed into an industrial scale waste reduction solution, especially because industrial slaughterhouse have facilities to collect and process the cow blood into for example fertilizer, which also means not all blood is waste, but all of it is invisible.

Basse Stittgen, Blood Related, 2017-ongoing

From what i know, it is now very difficult to have contact with slaughterhouses and be granted an authorisation to visit their premises? How did you manage to source the blood? And how was your own experience of dealing with that industry?

It is indeed very difficult to find access to slaughterhouses since they are quite suspicious towards the motives of outsiders that want to gain access and on the other hand many of the ones I contacted saw no value in my research. It is about finding the right person to work with and now since over a year I’m working with one slaughterman that lets me collect the blood which for him is waste he pays for to have it picked up usually.

I remember the first time going to the slaughterhouse I was afraid of what I might see, especially since all the footage and news from slaughterhouses painted a very dark picture in my head. The moment I could talk to the slaughterman in person a lot of that fear and prejudice disappeared, which doesn’t change that the killing of a cow was one of the most violent images I experienced in my life.

While doing some online research to prepare this interview i found this page that describes the properties of the material. Where there characteristic of the materials that you found surprising, that you were not expecting?

And is it possible just by smelling or touching it to guess the origin of this biomaterial?

On first glance the material resembles bakelite, the surface is very hard and smooth due to the pressure and due to the heat the objects are completely black. During the process of creating them, especially drying the blood you can smell the origin, once the blood is dry it becomes odourless which makes it almost impossible to guess its origin. What surprised me most is the simplicity of the process

Basse Stittgen, Blood Related, 2017-ongoing

Could you tell us about the transformation process? How did you get from ‘industrial waste product’ to this set of objects?

All the objects relate to certain aspects of my research around blood. For the show at MU I decided to create a tiled table filled with dining ware made from blood. The setting calls in mind a slaughterhouse and the objects are directly linked to the consumption of animals.

For me to understand the meaning of the material and see the transformation process it is necessary to go one step before the industrial waste product. The first and more drastic transformation goes from blood as the ‘substance of life’ to ‘industrial waste product’ and only then into the blood objects. I try to embody this transformation for example in the record from blood which plays the hearbeat of a cow.

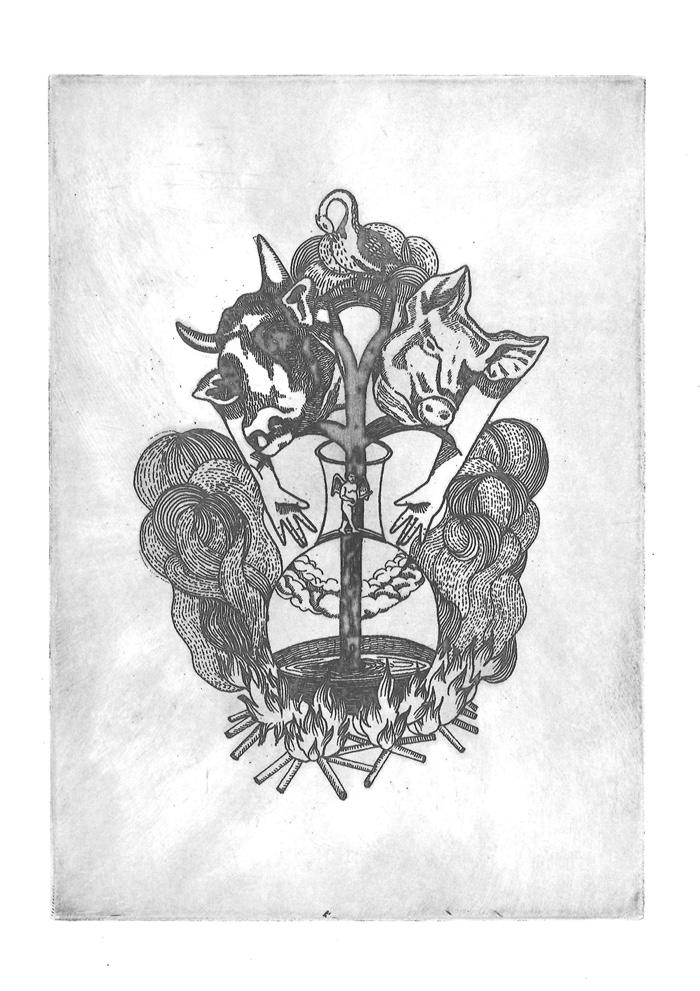

Basse Stittgen in collaboration with Anais Borie, Blood Related, 2017-ongoing

Basse Stittgen in collaboration with Anais Borie , Blood Related, 2017-ongoing

Together with Anais Borie you created a set of alchemistic drawings that echo the mystical dimension of blood. Could you tell us the role that blood played in alchemy?

While blood has its real attributes and composition of different proteins glucose and hormones that are all measurable and can refer to the visible, it has another layer which is its metaphorical meaning, the meaning humans give it based on nothing but belief and fantasy, the invisible. It is the interplay of those two sides is what makes it such a fascinating material to work with. By creating this visual layer based on alchemistic drawings I wanted to play on the irrationality connect to blood.

Has the project altered in any way your relationship to animal products?

I’m still eating meat, but the project made me more aware and choose much more carefully when and how I do so, I think for consumers its very easy and convenient to look the other way when it comes to the process of how things are made. Especially in the slaughter industry, one of the biggest in the world, yet one of the most invisible simultaneously.

Thanks Basse!

Basse Stittgen’s work is part of the exhibition ReShape. Mutating Systems, Bodies and Perspectives at MU in Eindhoven until 10 March 2019.

Related stories: Vampires, crucifixion and transfusion. BLOOD is not for the faint-hearted, Bodily Matters: Human Biomatter in Art (part 1. The blood session), “Dangerous Art”: the latest issue of the (free) Experimental Emerging Art Magazine, The Meat Licence Proposal, interview with John O’Shea, etc.