“Wouldn’t It Be Nice” is not only the title of a 1966 song by the The Beach Boys, but also the title of an exhibition about wishful thinking in art and design at London’s Somerset House. Before its stop in the UK, the show was on at the Centre d’Art Contemporain in Geneva and at the Museum für Gestaltung in Zürich.

When Brian Wilson wrote the song he was imagining “what you can’t have, what you really want” so, almost in reply, the show proposes a “modest form of utopianism, a whistle of optimism for how things could be, set against a bass note of misgiving”.

The weapons of choice in this case are art and design and the changing landscape between the two, with “traditional divides falling away, yet the specific contexts for works for art and design remaining quite distinct.”

Ten artists and designers, plus another six in the so-called Studio in which temporary installations and performances take place, offer their take on other possibilities.

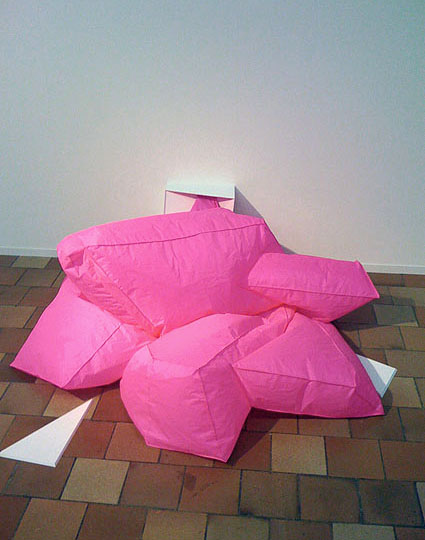

Alignment

Alignment

Dunne and Raby are showing a wide range of their work, including the bright, pink installation Alignment, created in collaboration with designer Michael Anastassiades. Their description of it is so good, I’ll just quote it in full: “A small pressure gauge indicates that it is operational. It could go off at any time. When the planets are in the appropriate configuration, the airbag is filled. An explosion of pinkness. It takes seconds, like an airbag in a car crash. Voluminous. Fantastic. A triclinic crystal: a form with no 90 degree angles. Perhaps no-one sees it, only the aftermath. A landscape of shocking florescent pink rip-stock fabric in sharp fractal forms, strewn across the living room floor. When the owner returns home, they decide what it means and what to do. It could be about love, money, or career.”

It means having an explosive piece of furniture to live with which could go off in a pink eruption at any time, associated with something that is important to its owner, however arbitrary and secret. It knows and when it goes off it means that something significant has changed and it will prompt a decision or demand a promise to be kept. It’s a strange and beautiful concept which has a great open-endedness about it in many ways.

MoF 94.7% (Photo: ©Francis Ware)

MoF 94.7% (Photo: ©Francis Ware)

Artist Tobias Rehberger is showing a “modular, easily assembled” sculpture called MoF 94.7% that visitors are invited to copy. After seeing the show, visitors can purchase a certificate which will render their replica-to-be an original artwork by Rehberger. If they send him a photo of their work, he will even add it into his own list of works and number it. The visitors’ work technically becomes a real Rehberger is “worth at least a thousand times more on the art market” than it would be as their own. Posing interesting questions about the notion of the original in sculpture and the age of digital reproduction (in a museum where they are really fussy about photography), he likens his sculpture to a mother and the copies to children which will be genetically similar in terms of the idea but all different in their appearances.

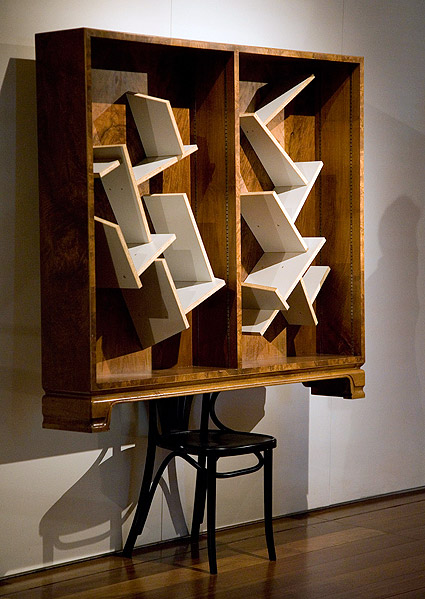

Collective Furniture (Photo: Sylvain Deleu)

Collective Furniture (Photo: Sylvain Deleu)

The work of designer Martino Gamper is interesting in the way that it reflects on the way we treat old things. In Geneva and Zürich, Gamper focussed on the “real needs of its employees and visitors”, scouring the cities’ junk yards and second-hand stores and then creating something new in an on-site workshop in an intense atmosphere that pushes him “towards work that is less conceptual and more driven by intuition and emotion.” At Somerset house, he focussed on ideas about storage and collection, creating huge shelves and hybrid furniture creatures.

The MacGuffin Library (Photo: Gunnar Green)

The MacGuffin Library (Photo: Gunnar Green)

Lastly, the initial exhibit in the Studio was Noam Toran‘s and Onkar Kular‘s MacGuffin Library, an intriguing laboratory of materialized narrative devices. Attributed to Hitchcock, MacGuffins are cinematic plot devices, usually an object, serving to keep the story in motion while lacking intrinsic importance in itself: “What everybody covets in the film and what drives the characters to move through space and time.” The mysterious glowing suitcase from Pulp Fiction is a somewhat recent example.

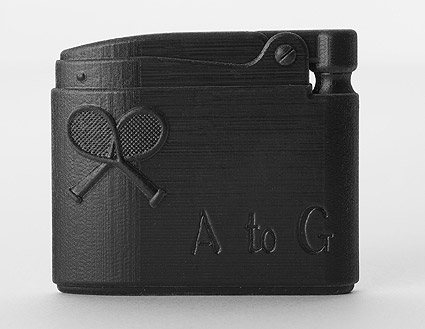

Hitchcock’s MacGuffin (Photo: Sylvain Deleu)

Hitchcock’s MacGuffin (Photo: Sylvain Deleu)

In the exhibition, the MacGuffin Library was presented as a lab-environment where objects are constantly being materialized using a 3D-printer and added to the collection on display. However, the narrative plots which they stem from are not necessarily cinematic. Apart from one nod to Hitchcock, they come “from a disparate range of interests and inspirations. Re-enactments, unorthodox fantasies, Borges and Carver short stories, forgeries, urban myths, high and low-brow cinema, alternative histories, and the relationship between media and memory.”

Objects taken from Sixteen narratives, created in collaboration with American writer Keith Jones include the original MacGuffin (a lighter from Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train), Hitler’s tea pot from Buckingham palace in the time of the Anglo-Nazi Reich, custom engine parts engineered for the Enthusiasts’ “civilian fantasy machines” and the carcass of a bald eagle from post-apocalypse America.

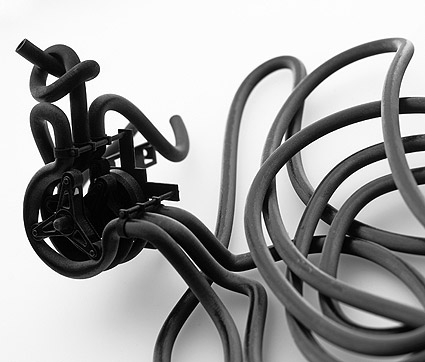

Civilian fantasy machine (Photo: Sylvain Deleu)

Civilian fantasy machine (Photo: Sylvain Deleu)

The MacGuffin Library takes its strength from the fact that a highly advanced fabricating technology as rapid prototyping, often regarded as the future of manufacturing, is being juxtaposed with the imaginary in the way that it gets to create objects from fiction. At the same time, this represents a very interesting approach to experimental storytelling, since in this case the fictional artifact is in a sense leapfrogging its usual role in theater and film and gets much closer to the audience who then takes it as a hook for their own imagination. Here, the objects make the story.

Wouldn’t It be Nice continues through December 7th. Currently in the Studio space is Chosil Kil, upcoming artists will be Dexter Sinister, Åbake, Europa and Ryan Gander and Julia Lohmann.