I usually associate industrial design with a high dose of virile technology, some big yawn ideas and a pretty lame design. I’ve seen enough Industrial Design graduation shows to say that only part of my lack of enthusiasm is due to my very own and very deep ignorance. However there’s one ID show i’m always happy to check out when June comes and graduation shows pop up all over London. It’s the MA Industrial Design (MAID) at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design. The graduates projects are smart, funny, the design is yes! the design is good and they manage to created a quirky scenography to make the visit even more enchanting.

That’s why, dear readers, in my quest to always inform and entertain you, i’ve asked the Course Director of MAID, Ben Hughes, if he’d have time for an interview. Ben trained as an Industrial Designer in the UK, worked for consultancies in Taiwan and Australia and came back London where he’s been heading the course since 2000, writes about and practices design, and consults on industrial design, brand and marketing.

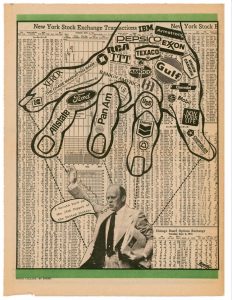

In last year’s department catalog, you wrote a collage “manifesto”: What can a collage approach offer to the design discipline?

The course has long encouraged the incorporation of collage into the design process. It is such a simple and powerful means of both generating and communicating ideas. It is also available to anyone with a pair of scissors and some glue. I first experimented with collage when I was studying for my own MA, influenced by a classmate from Spain (from where many of the Collage Maestros originate). He introduced me to the work of Joan Brossa and Max Ernst, etc. and I have been fascinated ever since. We have adapted the use of the technique for designers on the course and have run workshops with current maestros such as Graham Rawle and Sean Mackaoui. The article in the magazine is, in fact, taken from a forthcoming book; “The Secret Lives of Objects” by one of my former tutors, Jane Graves. Jane taught at Central for over 30 years and had a huge influence on the subject, particularly for the postgraduate students. This book is a collection of her essays, illustrated by my students using collage.

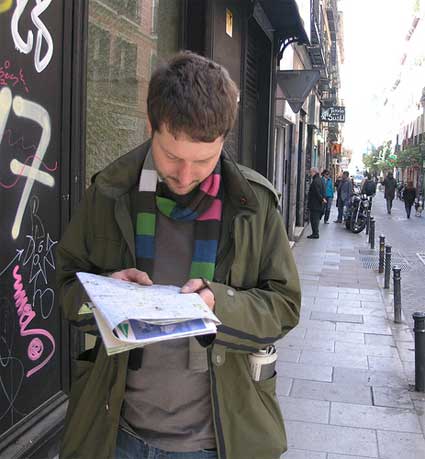

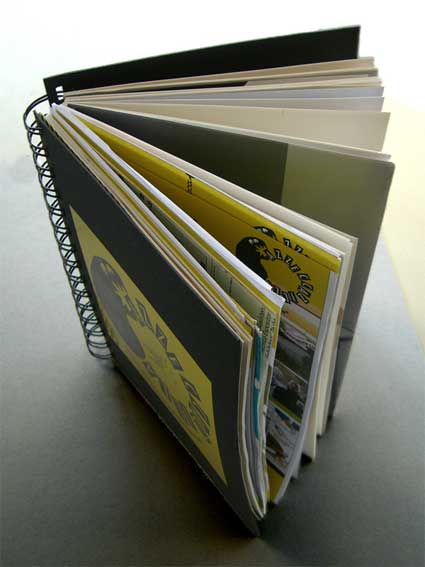

On a related theme – at last year’s Milan Furniture Fair, we mounted an exhibition workshop called Azzeccazilla, at the invitation of Stefano Mirti at NABA (Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti/ New Academy of Fine Arts). This involved each of our first year students scouring the whole of Milan for the most interesting design ideas and images, taking the brochures and leaflets concerned, and then collating them into beautiful spiral-bound A5 notebooks. Which we then sold to people for €5. Collage can be profitable, too!

On a related theme – at last year’s Milan Furniture Fair, we mounted an exhibition workshop called Azzeccazilla, at the invitation of Stefano Mirti at NABA (Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti/ New Academy of Fine Arts). This involved each of our first year students scouring the whole of Milan for the most interesting design ideas and images, taking the brochures and leaflets concerned, and then collating them into beautiful spiral-bound A5 notebooks. Which we then sold to people for €5. Collage can be profitable, too!

Our world is increasingly technology-mediated. How does it reflect on your course? Do you feel that students are more and more willing to engage with technologies like mobile phones or rfid system and develop projects that might sometimes look like they emerged from an interaction design department?

Our world is increasingly technology-mediated. How does it reflect on your course? Do you feel that students are more and more willing to engage with technologies like mobile phones or rfid system and develop projects that might sometimes look like they emerged from an interaction design department?

Certainly, we aim to adapt to the issues and technologies of the day, as well as the experiences of employers and graduates once they are in work. Industrial Designers need to be able to decode and evaluate these technologies so that they can incorporate them into products and services in a meaningful way. The term ‘Industrial Design’ relates, for me, to the mode of production, not to a dominance of particular archetypes or production methods. Enhancing a user’s experience, or making a product relevant to a particular group of people is core to the discipline. We have a number of projects every year that might sit comfortably with the category of ‘Interaction Design,’ but I am happier describing these in terms of Industrial Design i.e. how people relate to things.

We have been experimenting for several years with different means of prototyping interactive experiences in order to test them. We continue to incorporate everything from role-play to swift cardboard test-rigs to hacking existing systems, to basic programming. In terms of the latter, we have this year started working with Arduino, which look very promising. This year we also worked with colleagues in Textile Design and the Epigenome Network to explore ideas of Epigenetics using design thinking. I would draw the line at projects dealing with the entirely hypothetical, or ‘conceptual,’ as we are primarily interested in material culture; the 3 dimensional component of this stuff.

Several projects by last year’s graduates reflect on climate change, recycling and other eco-related topics. How present are the green issues in the course? Do you feel that sustainability and eco-consciousness will keep on taking a bigger place in the course? Do you see them as becoming an integral part of the course or will they appear only in separate lectures and workshops?

Projects that deal with these issues in one way or another have been part of the landscape, and rightly part of the responsibility of design education for over thirty years. Improving efficiency, reducing waste, and a focus on real, as opposed to created, needs are central to the skills and motivation of a good designer. That doesn’t mean that we disregard market-orientated projects, though. We cannot afford to be shortsighted – it could be argued that industrial design is part of the problem in which we now find ourselves. With any luck, it could also form part of the solution. Every project in the second year is expected to incorporate an ethical dimension, but it is up to the individual concerned to determine the prominence of this. For over 5 years we have had a regular first-year project dealing with ecological issues. Last year we teamed up with Natalie Jeremijenko and her students at NYU to share the findings of these. I am hoping to repeat the experience next year.

What’s with that Benjamin socket adapter on the pages of your course catalogue and personal website?

This was given to me by an ex-student. He (and it) is from Colombia, where, as I understand it, if you go into a hardware shop and ask for a ‘Benjamin’ you will be given one of these. There is no confirmed story as to why this is, but the most popular version has it named after Benjamin Franklin. I have always loved this kind of thing, which is both very clever and somewhat dangerous. I have some adapters from China, which will accept any plug from any country, although I am not sure it conforms to any British Standard. I also have a device that will recharge any mobile battery from any phone without any special adapters (the so-called ‘Omnipotence Charger,’ which has to be seen to be believed). The picture of me dressed up as a ‘Benjamin’ is part of an ongoing series that we have on the course, where students dress up as famous designers, or as in this case, designs.

Thomas Ballhatchet, Hamster Shredder

Thomas Ballhatchet, Hamster Shredder

Could you pick up some projects from recent graduates and explain to us why and how they reflect the spirit of the MAID course?

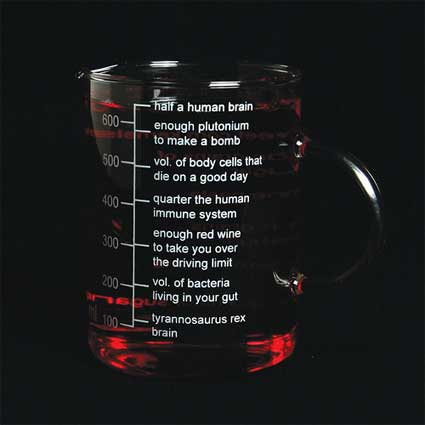

During the second year of the course, students pick their own area of study. A couple examples from this year’s show that come to mind are by Harry White and Tom Ballhatchet. Harry had a career prior to moving into Industrial Design as a scientist, working in the field of Genetics. He managed to combine this experience in a series of products that enable a user to better conceptualize certain scientific constructs. One of these is a set of measuring jugs that use unfamiliar units such as “ten billion grains of icing sugar” (not much) to “a tyrannosaurus rex brain” (even less), accompanied by a specially written recipe book, also employing these units. Harry also produced a set of “evo-cut” cutlery which demonstrate the basics of natural variation and gene mutation, and a “one-in-a-million” poster which depicts very clearly what this much-used expression really means.

Harry White, Measuring Jug

Harry White, Measuring Jug

Tom Ballhatchet, on the other hand, was concerned with issues of waste and re-use. One of the things revealed through his research was the mystery, or opacity surrounding the majority of recycling initiatives. i.e. the reluctance of people to contribute to schemes where the benefits were only faintly evident. His response was to try to localize some of this activity, and therefore lend it some more meaning. Tom managed to demonstrate this through two very different products: the Hamster Shredder, in which the inhabitant participates in the manufacture of its bedding material; and the TV Packaging Stand, which combines both the packaging, and furniture for a flat panel TV.

Tom Ballhatchet, TV Packaging Stand

Tom Ballhatchet, TV Packaging Stand

I would say these two projects are representative the MAID course in three ways: firstly because of their sound application of a number of research techniques; secondly their confident but playful approach to innovation; and thirdly because they each achieved well-resolved final outcomes.

What is the idea behind Claystation? How well does this method of encouraging the audience participation work?

The Claystation project was born just over 5 years ago, when Piers and Rory at Designersblock were kind enough to let an outfit called the Design Transformation Group (of which I am a director) hold an event as part of their London exhibition. The principle motivation was the removal of ‘white cube’ reverence towards design objects, particularly in exhibitions. The method was to get a quarter of a ton of plasticine delivered to the show and then sell blocks of it to visitors, who then spent time making things and then animating them on a makeshift stage. We filmed the whole lot in stop-motion. It is somewhat painful to watch, although it gets better later on (it lasts over 10 minutes), as we worked out the basics of animation. The soundtrack is provided by a DJ working with samples created from instruments made by my students.

Claystation 03 designersblock, Tea Building, London 25th-28th September, 2003

Claystation 03 designersblock, Tea Building, London 25th-28th September, 2003

This first exhibition was a big, and unexpected success, and has been adapted to many different formats over the years. We have found the Claystation format to be useful with students in generating quick 3d responses to briefs. There is now an architectural version, a product version, a chair version, a bag version, and most recently an automotive version. This year I worked with companies such as Porter International and NICE car to put on interactive exhibitions in London, Milan and New York. In Scotland, I have worked Alex Milton on the furniture version at the National Museum, and we are planning one with a sustainability theme for the Scottish Parliament next year.

Pongovision at designersblock Milan 2005, 23rd – 26th April, 2005

Pongovision at designersblock Milan 2005, 23rd – 26th April, 2005

Over the course of their design studies, students are often free to let their creativity run wild. How much is it still possible after they have left the school?

That depends largely on where they target their efforts. I have had ex-students express frustration with jobs. This is not because they think they are too good, but rather that their working lives are eaten up with so much tedium. At college you are encouraged to believe that design can make a difference, and to explore the ethical, and aesthetic alongside the actual business of design. This is right and proper. But it can seem a bit distant when you find yourself in a meeting, or even in a job, where the entire focus seems to be on cutting costs. Many of our students are lucky to get themselves into positions which focus on research, or design management. Many also set up their own businesses.

Sustainable fashion, online service, eating behaviour, etc. The work of your students embrace so many aspects of design. Is there any aspect of life left untouched by industrial design? How broad is the discipline?

Sustainable fashion, online service, eating behaviour, etc. The work of your students embrace so many aspects of design. Is there any aspect of life left untouched by industrial design? How broad is the discipline?

If it’s an aspect of life that involves people, things and production, then no, not really. Many people appear nervous about defining what they do as ‘industrial design’ because it seems too broad, or maybe ‘old-fashioned.’ I don’t have a problem with any of this, and consider myself lucky to work in an inclusive discipline that incorporates the widest variety of practice, particularly at postgraduate level. My background is in retail design and consumer electronics, but the course can support much more diversity than this as our team of contributing tutors and mentors are drawn from all specialisms.

Who are the designers, artists or architects who inspire you most?

I am inspired by anyone who is clearly in love with the possibilities of invention; anyone who manages to do something well by doing it differently. Although I didn’t really understand what he was doing with his last show in Milan, Marcel Wanders is clearly one of these people. As is Gaetano Pesce. I have always admired Denis Santachiara‘s work, which is full of invention, irreverence and wit.

Recently, I have really enjoyed Maarten Baas‘ stuff. He seems to be in the same mould as the others I’ve mentioned, whilst lacking the pretension of many emerging ‘stars.’

Closer to home, I think designers have a huge amount to learn from Tim Hunkin. As far as art is concerned – the things that make most sense to me are the those that reveal something about the nature of objects, mass production and consumption. So Oldenburg, Duchamp, Cornell, Joan Brossa, Chema Madoz are favourites. Also Richard Hamilton- not only did he make his name through collage, has also worked with readymades (famously including a Braun electric toothbrush), but he also worked for part of his career as an industrial designer.

Thanks Ben!

The MAID course will do a couple of shows from April 16 to 21, during Milan Furniture Fair. One in Satellite and one at NABA, Via Darwin 20 (map).

Course catalog

Course catalog