Works of Game. On the Aesthetics of Games and Art, by John Sharp, Associate Professor of Games and Learning at Parsons.

Publisher MIT Press writes: Games and art have intersected at least since the early twentieth century, as can be seen in the Surrealists’ use of Exquisite Corpse and other games, Duchamp’s obsession with Chess, and Fluxus event scores and boxes–to name just a few examples. Over the past fifteen years, the synthesis of art and games has clouded for both artists and gamemakers. Contemporary art has drawn on the tool set of videogames, but has not considered them a cultural form with its own conceptual, formal, and experiential affordances. For their part, game developers and players focus on the innate properties of games and the experiences they provide, giving little attention to what it means to create and evaluate fine art. In Works of Game, John Sharp bridges this gap, offering a formal aesthetics of games that encompasses the commonalities and the differences between games and art.

Myfanwy Ashmore, Super Mario Trilogy

Works of Game is part of MIT Press’ Playful Thinking, a series of compact, short, sharp volumes on game-related topics that should interest pretty much everyone, from academics to industry professionals to members of the general public. I’ve only got this one book from the series but i can confirm that it counts some 115 pages only (excluding the notes which, by the way, are surprisingly amusing to read) and that it analyses its subject in depth while remaining extremely readable to art experts and curious players alike.

In the book, John Sharp attempts to explore the way game makers and artists conceptualize and create game-based artworks. He identifies three connected community of practice:

Game artists appropriate the tools of the video game industry to create art.

Meanwhile, the artists who produce artgames see games as a medium for artistic expression and experiential understanding that enable them to delve into territories traditionally explored through poetry, painting, literature or film.

And finally, there are the creators who produce artists games and use games are a vehicle for questioning, critiquing and exploring unexpected potentials. The main characteristic of their work is that their concept and interactivity speak to both the contemporary art and the game communities.

Sharp illustrates the three practices with examples and brings them in parallel with key moments or players of the history of art. It is one of those rare books in which Donkey Kong finds itself in the company of Marcel Duchamp, Dune and Raby, Nicolas Bourriaud and Sol Lewitt.

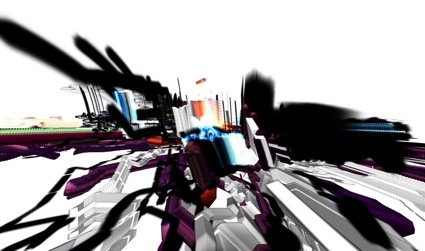

Julian Oliver, ioq3aPaint, 2010

Julian Oliver, ioq3aPaint, 2010

A clear example of Game Art is when Julian Oliver exploits a bug in the Quake 3 game engine to ‘paint’ abstract images and videos. The result is a wok of art that stand on its own but that might not necessarily appeal to a gaming community who expects interaction.

A great artgame would be Castle Doctrine, a massively-multiplayer game set in the early 1990s. Each player has two missions: protect their home and break inside other players’ houses and steal money from their vaults. It’s not pleasant, you can lose everything and commit suicide, be mauled by a guard dog, or be killed by the traps your neighbour has installed to protect their belongings.

In creating this paranoid game, Jason Rohrer was influenced by his childhood fear of his house being robbed, shootings that made the headlines, and his own political views regarding gun rights and home invasions. Castle Doctrine demonstrates that a game can be autobiographic, like a painting or a poem.

Brenda Romero, Train, 2009

Brenda Romero, Train, 2009

In her The Mechanic is the Message series, Brenda Romero uses games as a medium for exploring human tragedy.

The series is composed of six separate non-digital games that experiment with the traditional notions of games and the way they can extend human experience and create emotions not traditionally associated with games.

One of them is Train, a board game where players have to transport as many yellow game pieces from one end of the game board to the other. But the winner discovers the name of their destination only once they’ve reached it. All of them are concentration camps. The player can then choose to stop playing or attempt to sabotage the game by intentionally trying to draw derail cards.

Another game, Síochán leat (aka “The Irish Game”) re-creates Oliver Cromwell’s mid-17th century invasion of Ireland. As the English army advances, the Irish people (game pieces) are displaced onto other squares of the board until the figures representing Irish people can barely squeeze into increasingly crowded areas. Two players manipulate the Irish pieces. When there isn’t enough free spaces left, the Irish people will have to fight one another in order to stay alive, for example by sending some of the Irish people to one side of the board where they will wait to shipped to Barbados to serve as slaves.

All the games in the series put the player in the very embarrassing position of playing an active part into a human atrocity. The rules of the game are not published anywhere, you discover them as you play.

Now artists’ games have the best of both world. They satisfy the art community because of their critical and conceptual rigor and they entertain the gamers with their level of interactivity and their representation of real phenomena experiences.

Mary Flanagan, [giantJoystick], 2006

Mary Flanagan, [giantJoystick], 2006

An example of artists’ game is Mary Flanagan’s [giantJoystick] which critically engages with the design, play and cultural place of games. In the installation, you have to handle an oversize Atari VCS joystick to play classic games designed for one player. However, you need the help of another player in order to successfully manipulate it. The idea is thus very simple. However, questions soon arise in the mind of the player: How do you collaborate on a game that was designed for one player only? How does the playing activity change once you’re in a museum rather than alone in your living room? etc.

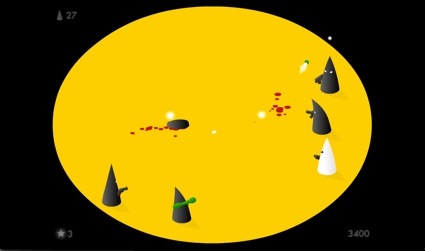

Molleindustria, The Best Amendment

Molleindustria, The Best Amendment

Molleindustria’s The Best Amendment, a game that pushed the pro-gun rhetoric to its most absurd limits, is as ludic as it is socially-engaged and as such, it appeals to both the game community and the art crowd. It particularly challenges Wayne LaPierre‘s argument, made in the wake of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, that “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.”

In the concluding pages, Sharp states that the artgames movement is more or less on its last leg and that game art is relegated to the ‘marginalized world of media art.’ He does however make a great case for artists’ games, explaining why they deserve to get the attention of galleries and museums, what is their place in culture and also why we should develop a new literacy to better appreciate (and create) them.

Now who might enjoy this book? That’s a no-brainer!

Works of Game is a book for people who love contemporary art and read Jonathan Jones’ art column on The Guardian (i like Jones’ writing but his good sense seems to evaporate as soon as any form of technology is involved.)

It is also a book i’d recommend for gamers, for the media art crowd and anyone else who want to further reflect on art’s contribution to games. And vice-versa.