Deep space is a vacuum, it doesn’t carry sound waves as air and water do. With no medium to travel through, outer space remains (mostly) silent. Except of course in the universe of film and television!

Tamara Shogaolu, Echoes of Silence, 2020. Ado Ato Pictures

Tamara Shogaolu, Echoes of Silence, 2020. IDFA Doclab night at the Planetarium. Photo: Nichon Glerum, Amsterdam, 22 November 2020

Echoes of Silence, which recently premiered at ARTIS Planetarium in Amsterdam during IDFA DocLab, translates in a full-dome experience the many ways sound designers working for the film industry have imagined the sounds of outer space but also how each continent and culture have different ideas about the kind of noises that fill in the vast expanse between planets and stars. The immersive audio experience with dome projections takes the viewer on a trip into space. The animations and images of starlit skies as they are observed from various parts of the world are accompanied by the sound of space used in films and TV series at each location. The project highlights the universal sense of wonder about what lies far beyond our atmosphere but il also implicitly questions the predominant Western view of space.

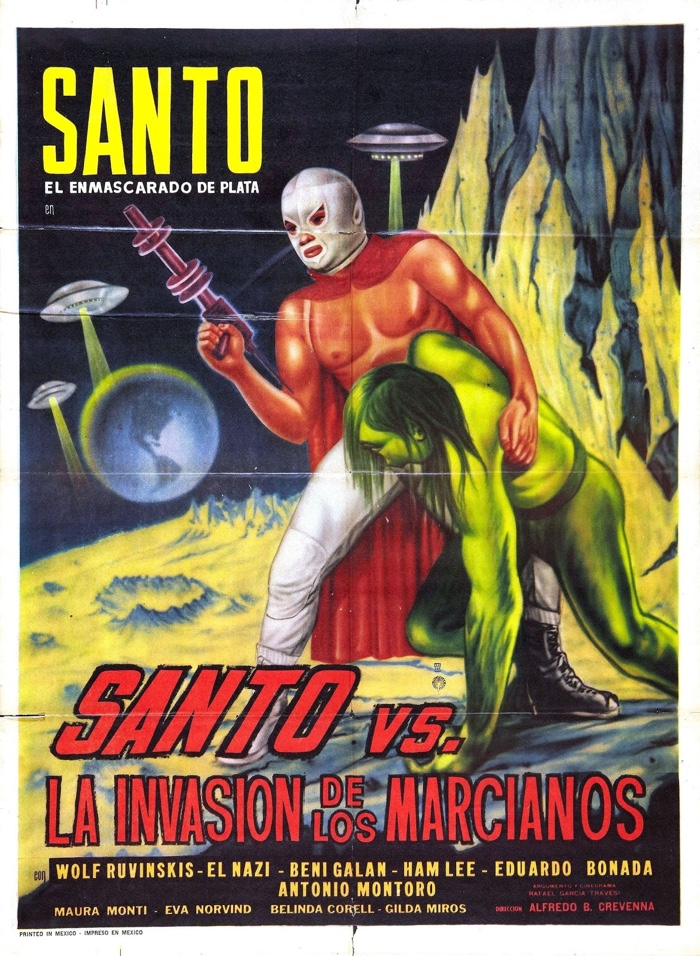

Alfredo B. Crevenna, Santo Contra La Invasion De Los Marcianos / Santo vs. the Martian Invasion, Mexico, 1967

For millennia people from every part of the world have tried to understand celestial bodies. In Mesopotamia, Ancient Greece, Persia, India, China, Egypt and Central America, astronomical observatories were built, maps were drawn to represent the position and movements of celestial objects. Unfortunately, as dominant cultures homogenised languages and customs, they also marginalised and even dismissed other views of the skies, especially the ones expressed by cultures that recorded their beliefs orally, like the Navajo or the Hawaiians.

Echoes of Silence, developed by Director Tamara Shogaolu and her studio ADO ATO Pictures, brings to light how early films from various parts of the world echo some of those sidelined perspectives:

We discovered that in Pre-Star Wars films not only was there a variation in the way different cultures visualized space but that there were regional trends in the design of their soundscapes. Japan’s militaristic culture reverberates in the soundscapes of their plentiful science fiction cannon. Native American filmmakers have suggested the relationship between earth and space is more peaceful. Mexican films portray extraterrestrials coincidentally similar to Lucha Libre wrestlers. However, as the decades progressed euro-centric portrayals of space became more dominant and pervasive throughout the world. Through Echoes of Silence, we aim to memorialize all sounds of space.

Tamara Shogaolu is a filmmaker, immersive artist and she is the founder and Creative Director of the award-winning film and XR studio Ado Ato Pictures. I caught up with her over Skype during IDFA Doclab:

Hi Tamara! I love the premise of the work and this idea that space and all celestial bodies sound differently depending on where you are in the world or depending on your culture. How did you discover these differences?

When I was in film school, one of my professors, Tomlinson Holman, was a Creator of THX who started his career working on George Lucas films. I remember a lecture in which he was telling us about the process of sound design in Star Wars films and how back then the sound libraries you had at your disposal for space were very limited. They were a bit cartoony. With 3 other guys, he started building up a sound library for outer space, making weird sounds using vacuum cleaners and other objects to make out this universe.

I realised that what they did back then shaped the way that most of us think about space and what it sounds like. The irony is of course that there is no sound in space. It’s all from human imagination.

From there I started wondering if there were other interpretations of space by other people living in different parts of the world. I thus started researching and creating an archive of films from around the world set in space. I watched and listened to many of them. I studied sound design a bit when I was in film school. And I started to notice that there were trends in the way the sounds were used. Star Wars marked a defining moment. It influenced the way the same libraries were used and interpreted and the kind of messages they conveyed in relationship with the storytelling.

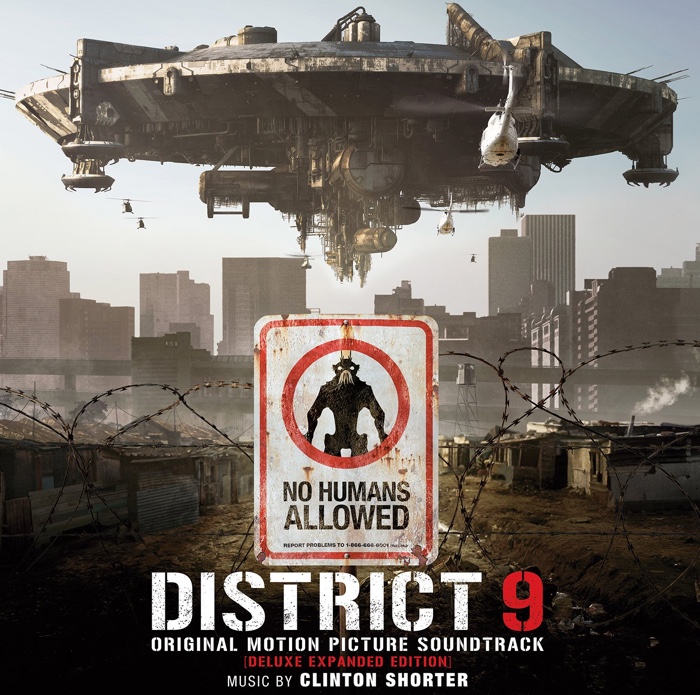

Neill Blomkamp, District 9, 2009. South Africa

Ishirō Honda, Space Amoeba, Japan, 1970

Can you talk about some of the differences of interpretations depending on cultures and geography?

I found that most Latin American films use more humorous undertones. It’s all very exaggerated. Whereas there is more of fear undertone in most US and European films. You get a sense of the unknown, of the presence of dark forces. You sense that in Star Wars of course but also in 2001: A Space Odyssey and in so many other films.

Asian films were also interesting to listen to because there is more, let’s say, diplomacy in sound design, including when aliens appear. Even in some of the Godzillas films, there wasn’t such a strong component of fear. If you look at one of the stars charts that were used 100s of years ago by emperors in Japan, you will see how the stars were used to show that these emperors were meant to be in power. Stars were woven into diplomacy in a certain way and you can still see some threads of that today in the way sound is being used in cinema.

We also found some Native American films, especially some Lakota and Navajo films, and even though they were made in the U.S., they were very much about a friendly environment in terms of what the stars say about our lives. It was interesting to see how traits from indigenous knowledge from hundreds of years ago had filtered into the way that the sound was being implemented and designed.

We made a public archive so that people can find the films. They also have a possibility to suggest films that should be added to the archive.

Tamara Shogaolu, Echoes of Silence, 2020. IDFA Doclab night at the Planetarium. Photo: Nichon Glerum, Amsterdam, 22 November 2020

Tamara Shogaolu presenting Echoes of Silence during IDFA Doclab night at the Planetarium. Photo: Nichon Glerum Amsterdam, 22 November 2020

As your work reveals, the way we represent space differs according to where we are. What about time? Has the way space is being sonified evolved over time or are we stuck in early sci-fi ideas of what space sounded like?

I think there are some films now that try to better respect reality. Gravity, for example, tried to make the space experience more realistic.

Our piece basically travels through the world and the sounds come from archival sounds used in all those films. When you go into the actual space, you experience leaving the Earth, those are sounds from the NASA library.

I was curious about the human imagination and how not only space but also the way we imagine space can be colonised. I was wondering how we can question this colonisation of human imagination, how can we make it more inclusive and involve different perspectives on space sounds and what we imagine to be out there and, from there, we could build up an imagination from us as a whole planet. You often hear about how astronauts, when they leave the Earth, start seeing their country and then their continent until they finally realise that we are one planet. The ways we imagine space, the way we design it can be connected to the way that we relate to our environment or learn from our surroundings. And that whole process could be more inclusive.

Space research and the world of extended reality seem to be dominated by white male individuals. Black female filmmakers don’t have the same opportunities. Black female characters are deemed less appealing. Has Black Lives Matter changed that?

I think it’s too soon to tell. When something happens, people tend to have an immediate strong response but after a while the attention shifts. I think that the pandemic has made it possible for some people to hyper-focus on the representation issue.

Last week, I was in a summit for a conference dealing with the African diaspora and people were talking about how they were living in Europe, about the Afropean identity and what that means to have a bi-cultural identity. Some filmmakers were saying that they had to prove that they can do big box office films when in reality black filmmakers already have and continue to make successful films. There have been exemplary works in music, art and films made by black people and yet these people are still seen as anomalies, as not being the norm.

As a black woman working at the intersection of film, tech and animation, I’m often questioned and asked whether I can actually deliver some of my ideas. I’m very aware of that but it is part of my existence and I don’t really know anything else.

There is definitely more openness in discussing the work this year and I think that, because of the pandemic, people are more open to exploring the possibilities of digital experience for connecting people but I still feel that the people who make the decisions are the same. I don’t know if it’s just a fad and something that will pass but having black, indigenous or native people around the world involved in telling their own stories and in creating content would be better for the whole world. I hope this is not just a passing trend. I have noticed the change but I’ve also noticed how people from big companies reach out saying they want to support my work but months pass and you don’t hear from them again. I don’t want to be too pessimistic because I’ve seen how some organisations have put on the effort to make a change and bring diversity to their content and the artists that they support but I’ve also seen how others didn’t go much further than posting something on social media. The gate-keepers and those making the decisions are still the same.

Echoes of Silence marks the first time you work on a full-dome experience. What were the challenges of creating for a dome?

Honestly, it was super challenging and I have so much respect for anyone who works in full domes! From a director’s point of view, it was very challenging because you are working on a grid and the sense of space is totally different. It is not at all like in VR. When you are directing in VR, there is the 360 space where you are still at the same level and you have a sense of the world that surrounds you. With a dome, everything changes: things appear different in height but also in distance and placement. There are multiple dimensions that I have to think about when working on a composition. I was very lucky that I could go to the planetarium here in Amsterdam and that I had a crash course with the head of the planetarium who would watch different cuts and give me feedback. That was amazing.

The dome required a totally different process. We made a model of the planetarium in VR and then we would project the planetarium in the headset in order for me to be able to check some details. But then we would go to the planetarium and stuff would be flipped. It was a surprise every time even until the very last test that we made. Every planetarium is different: they vary in sizes, the brightness of the projector changes, etc. As a result, the composition of your picture can change from one planetarium to another. I work in animation and transitions are super important in animation. What looked good inside headset had then to be tested inside the planetarium hoping it would look good there too but then once arrived there, we’d realise that everything was backwards. It was very challenging but I learnt so much. As a director, I started thinking about space in different ways, even with the 2D films I’m working on now. I have acquired a different sense of space and camera movements after this experience at the planetarium.

So the work was site-specific and if you had to show it in a different planetarium, you would have to adjust to the new space again?

Yes, but we also made a VR version of Echoes of Silence which will stay constant for people who want to experience it. I wanted to create something positive for people, let them travel around the world and escape for 7 minutes. The best is to experience while laying it on the floor.

The work seems to require so many skills and competence. How many people were working on Echoes of Silence?

That’s just the two of us. It was mostly me and my editor. The budget was tiny but we still managed to work with a sound composer, a sound designer and a sound mixer. They did an amazing job. The sound is an important part of the experience. It was very much a two women-propelled project and many sleepless nights working together but we got to work on all aspects of the piece and that is always exciting.

Thanks Tamara!

The Ado Ato Pictures team has also created a scalable version of Echoes of Silence that you can experience on your phone with a VR headset. It should be made available shortly. Echoes of Silence is the winner of the 2020 Netherlands Film Fund DocLab Interactive Grant. It was part of the IDFA DocLab Competition for Immersive Non-Fiction.