A couple of week ago, i was back at the VivoArts School for Transgenic Aesthetics Ltd., Adam Zaretsky and Waag Society‘s temporary research and education institute in Amsterdam.

On the menu that day was a Tissue Culture Lab headed by tissue engineering artist Oron Catts. Catts is the co-founder and Artistic Director of SymbioticA, the Art & Science Collaborative Research Laboratory, at the School of Anatomy and Human Biology, UWA. He is also the founder, together with Ionat Zurr, of the Tissue Culture & Art Project.

Wikipedia defines tissue culture as follows: the growth of tissues and/or cells separate from the organism. This is typically facilitated via use of a liquid, semi-solid, or solid growth medium, such as broth or agar. Tissue culture commonly refers to the culture of animal cells and tissues, while the more specific term plant tissue culture is used for plants.

I’ll come back to the hands-on wet lab in an upcoming post. For now, here are some notes i wrote down during a talk that Oron Catts gave to kick off the workshop. His presentation, which put our workshop into a historical narrative, was titled An alternative timeline for regenerative medicine – A biased history.

As HG Wells wrote back in 1895, life is becoming something for us to engineer:

‘We overlook only too often the fact that a living being may also be regarded as raw material, as something plastic, something that may be shaped and altered.’ HG Wells, 1895

In 1885, Wilhelm Roux removed a portion of the medullary plate of an embryonic chicken and maintained it in a warm saline solution for several days, establishing the principle of tissue culture.

The first successful human transplant was a corneal transplant performed in 1905 by Eduard Zirm in Olomouc, Czech Republic.

In 1907 zoologist Ross Harrison successfully perform the first partial life entity. He demonstrated the growth of frog nerve cell processes in a medium of clotted lymph.

In 1913, surgeon, biologist and eugenicist Alexis Carrel grows cells in culture for long periods -fed regularly under aseptic conditions. In 1912, Carrel took tissue from the heart of a chicken embryo to demonstrate that warm-blooded cells could be kept alive in the lab. This tissue was kept alive for thirty-four years — outliving Carrel himself — before it was deliberately terminated. His experiments horrified his contemporaries. It has sometimes been said that his lab in Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research inspired Hollywood’s Frankenstein.

Interestingly, this practice of fragmenting the body and keeping the cells alive was called “Artificial Life” at the time.

In 1913, Ross Harrison noted the epistemological contradictions regarding tissue culture:

‘…it seems rather surprising that recent work upon the survival of small pieces of tissue, and their growth and differentiation outside of the parent body, should have attracted so much attention, but we can account for it by the way the individuality of the organism as a whole overshadows in our minds the less obvious fact that each one of us may be resolved into myriads of cellular units with some definite structure and with autonomous powers’

Eduard Uhlenhuth wrote in 1916 “Through the discovery of tissue culture we have so to speak created a new type of body on which to grow the cell.”

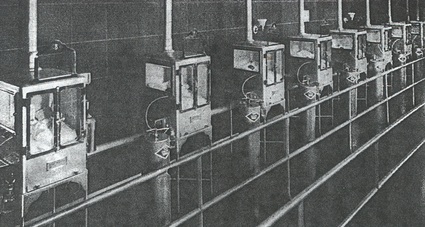

Dr. Martin A. Couney’s exhibit at the Century of Progress Exposition, Chicago, 1933-1934

Dr. Martin A. Couney’s exhibit at the Century of Progress Exposition, Chicago, 1933-1934

The first premature baby wards in the US were part of a freak show called “Oddities of Life.”

From the 1910 till the 1930, tissue culture starts to be regarded as science by scientists. They start to see an utilitarian end to it, it’s not just a curiosity anymore.

1948 saw the first animal cell line established (mouse). Those cells tcan be considered the oldest living parts of a mouse.

1951 first immortal human cell line established. HeLa. The cell line was derived from cervical cancer cells taken from involuntary donor Henrietta Lacks, who died of cancer that year.

1951 first immortal human cell line established. HeLa. The cell line was derived from cervical cancer cells taken from involuntary donor Henrietta Lacks, who died of cancer that year.

The cells were propagated by George Otto Gey without Lacks’ knowledge or permission and later commercialized. There was no requirement to inform a patient, or their relatives, because discarded material, or material obtained during surgery, diagnosis or therapy was the property of the physician and/or medical institution. This issue and Ms. Lacks’ situation was brought up in the Supreme Court of California in 1990 but the court ruled that a person’s discarded tissue and cells are not their property and can be commercialized.

HeLa cells are termed “immortal” because they can divide an unlimited number of times in a laboratory cell culture plate. It has been estimated that the total number of HeLa cells that have been propagated in cell culture far exceeds the total number of cells that were actually in Henrietta Lacks’ body. The cells traveled around the globe- even into space, on a satellite to determine whether human tissues could survive zero gravity- and have been used for research into cancer, AIDS, the effects of radiation and toxic substances, gene mapping, and countless other scientific pursuits”. HeLa cells have been used to test human sensitivity to tape glue, cosmetics, and many other products (source.)

Cell lines are usually dehumanized but the story goes that one night, a surgeon working with HeLa cells realized that he was working with a person’s cell while he was having dinner with a relative of Henrietta. Neither Henrietta nor her family had given permission for the cell line. They wanted her contribution to science to be respected and her cells to be sort of ‘rehumanised.’

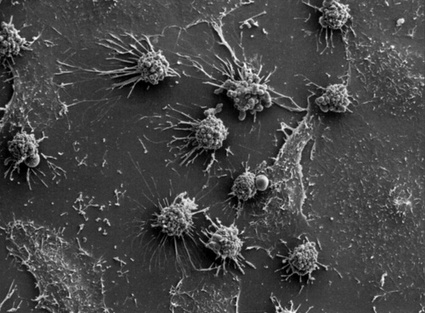

HeLa cells

HeLa cells

1954, the field of tissue culture becomes more standardized.

“I have sought to strip from the study of this subject its former atmosphere of mystery and complications. The grey walls, black gowns, masks and hoods; the shining twisted glass and pulsating coloured fluids; the gleaming stainless steel, hidden steam jets, enclosed microscopes and huge witches’ cauldrons of the ‘great’ laboratories of ’tissue culture’ have led far too many persons to consider cell culture too abstruse, recondite and sacrosanct a field to be invaded by mere hoi polio.” P.R White, The cultivation of animal and plant cells, New York, Ronalds Press 1954.

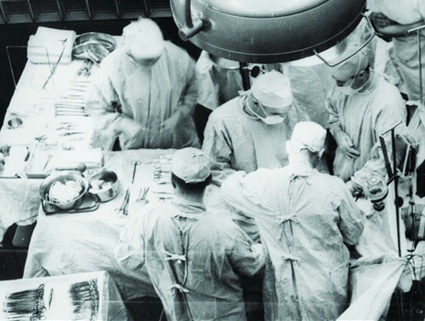

Joseph Murray performed the first successful transplant, a kidney transplant between identical twins, in 1954.

Joseph Murray performs the first ever live organ transplant (image)

Joseph Murray performs the first ever live organ transplant (image)

1978, Louise Brown, the world’s first baby to be conceived by in vitro fertilisation.

Publication of Langer, R & Vacanti JP, Tissue engineering. Science 260, 920-6; 1993.

Eastern Mud Salamander, Pseudotriton montanus

Eastern Mud Salamander, Pseudotriton montanus

We are becoming salamanders: our bodies can repair themselves and regrow lost parts using their own resources. In the ’80s, repairing the body was more mechanical, people would picture prosthetic limbs, heart pumps and mechanical organs. 10 years later, the image is the one of a body that relies on cells that have been engineered into 3D objects.

Previously: Image of the day, September programme of the VivoArts School for Transgenic Aesthetics and Day 1 at the VivoArts School for Transgenic Aesthetics: Seed broadcasting workshop.