It’s hard to believe that the first tourist flight into space might already be planned for next year. But Joseph Popper is probably not very impressed by the prospect because he came up with an idea so bold even Richard Branson would think twice before funding it. The designer believes that there aren’t many unknown territories for men to explore, really. One of the very few thrilling adventures left to mankind would be to send one person on a voyage into deep space from where they will not return.

And that’s exactly what The One-Way Ticket proposes to do.

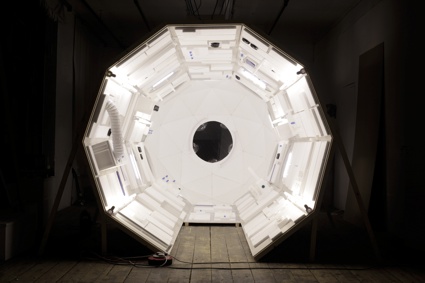

He obviously didn’t test the idea himself but designed film-making props, contraptions and sets that follow the dogma ‘zero gravity, zero budget’. The final short film comprises a collection of episodes transmitted from the spacecraft.

I need to repeat the idea: Send. One. Person. In. Space. Without. The. Prospect. Of. Ever. Coming. Back. And so i asked all the silly questions for you. Because that’s what i’m here for.

Hi Joseph! Your project proposes to send one person on a voyage into deep space from where they will not return. Who would want to go on such journey?

I believe a person willing to go would not be so hard to find. The project emerged from an observation that we are running out of unknown frontiers to explore in the expedition sense – certainly on our own planet and it’s near surroundings. Mount Everest, Antarctica and even the Moon have all transformed in our imagination from mythical bastions of discovery into touted destinations for extreme tourism. I am interested in this predicament, particularly surrounding ideas of space travel.

I propose a one-way journey as one of “the last adventures”. This is how skydiver Felix Baumgartner described his attempt to break the record for the highest, fastest jump from the edge of Earth’s atmosphere – so maybe he would want to go?

Is there a panic button? An emergency exit for the lonely traveler? Or is there really no way they can ever get back to earth? Is his or her wellbeing onboard ever monitored or catered for?

In my mind there is no panic button, no emergency exit, no return. The wellbeing for the astronaut is certainly catered for in order for them to complete the mission. In the project I focused more on different aspects of the astronaut’s experience inside the space capsule, rather than the external workings of the mission architecture.

Do you have an idea of how far away in space the spaceship would be able to go? Or would it just rotate around the Earth?

Do you have an idea of how far away in space the spaceship would be able to go? Or would it just rotate around the Earth?

The spacecraft passes Mars on what is essentially a fly-by mission, before continuing in the direction of Jupiter – eventually reaching around 90 million miles away from the Earth. The total duration is 2 years before oxygen, nutritional and other supplies are scheduled to run out. The aim is for the astronaut to be the first to reach Lower Mars Orbit, and then to travel on as far as they possibly can – this is premise for the adventure.

What about communication with the Earth? Is there any?

What about communication with the Earth? Is there any?

The issue of communication with Earth has certainly been an important part of my research. The further we travel away from Earth we are subject to longer and longer delays in our communication with it: when you reach Mars it takes about 27 minutes for any sort of transmission from your spacecraft to reach home. It is therefore impossible to hold a normal conversation between two distant planets, and this factor contributes to psychological issues that include isolation, loneliness and also boredom.

But is it technically possible? How would the rocket or spaceship be powered for such a long period of time? And does the spaceship ever return to earth or does it become space junk?

In designing the mission scenario I have tried to abide by existing space mission principles and hardware. Archived mission plans that were never realised have also been important starting points for deciding on the trajectory of the spacecraft and time frame of the voyage. So yes, I will say it is technically possible to send someone beyond Mars with the technology we have today.

The path is based on a route that requires the lowest energy consumption – employing a series of Hohmann transfers. This is where the spacecraft would use a short, powerful engine burn to escape Lower Earth Orbit before using the momentum to coast towards Mars for 258 days. The same principle would then apply for escaping Mars orbit to continue on its path… to eventually become space junk.

Film set

Film set

The text accompanying the work in the exhibition says “the exhibited works are a response to research into a range of human factors particular to the mission that also underline its extraordinary nature.” Could you tell us what these human factors are? Are they physical? Emotional? and what the lone trip has to do with them?

The human factors range across many different issues – from the physical to the psychological and philosophical. Many of these directly relate to existing concerns and research around actual long duration space missions, and also to living in more hostile environments like Antarctica or on the International Space Station. However, when you simply take “coming back” out of the equation many of the questions are thrown wide open again.

If you don’t come back to Earth: you will be forever weightless, you will never need to stand up again, the sun never sets or rises, you will never eat fresh food again (apart from whatever you can grow), you will lose sight of Earth for the last time, you never leave the confines of your capsule.

These hint at some of the various questions I explored in my research, leading to some very interesting debates and conversations with different experts. We can find many examples in space mission analogues that simulate certain aspects of a one-way voyage. However what struck me most is that, as we are talking about something completely unprecedented, we can only ever really speculate on what such a voyage would be like until someone actually goes.

Thanks Joseph!

All images courtesy Joseph Popper.

Joseph is going to talk about this project at Test_Lab: The Graduation Edition 2012 at V2_ in Rotterdam on July 5.