Euthanasia Coaster is a hypothetical euthanasia machine in the form of a roller coaster, engineered to humanely kill a human being. The rider is subjected to a series of intensive motion elements that induce various unique experiences: from euphoria to thrill, and from tunnel vision to loss of consciousness and eventually death. The whole process reproduces over a much longer period of time the sensations that pilots and astronauts experience during training when they are put through extreme g-force inside human centrifuge machines. The Euthanasia Coaster is of course a speculative project. People might want to experience this ultimate ride in the future, for example when their lives have been extended so much that existence has become unbearable. In addition, the roller coaster, with its spectacular succession of physical and mental sensations, brings back a sense of ritual to the contemporary handling of death (after all, people in England have been known to use fireworks to send the ashes of the deceased into the night sky.)

If you want to know more about the project you can take the fast lane and enjoy designer Julijonas Urbonas‘s cute Lithuanian accent in this video:

Or take your time and follow this conversation i had with designer:

You have a rather unusual bio for a designer, it states “In 2004, I became a managing director of an amusement park in Klaipeda, Lithuania, and ran it for three years.” Was it already part of your design research or was it a genuine job that had nothing to do with art and design and had no other purpose that making a living? What did your experience there teach you?

I grew up in a Soviet amusement park, which was headed by my father. The park was my substitute kindergarten and its employees – ride operators, event managers, technicians, cashiers, administrators – were my nannies. I witnessed the transition from communism to westernisation from quite a unique perspective of that architectural amusement. The entire Soviet Union was filled with these carefully crafted packages of standardised ‘military-grade’ amusement rides that functioned rather as communist propaganda machines, saturated with Soviet memorabilia, soothing and relaxing the labour force from physical and mental exhaustion. Once Lithuania became independent in 1991, the country’s amusement culture was also liberated and western forms of entertainment started to emerge. As a result of this, the park started to experience gradual decrease in visitor numbers, and the need for an upgrade was evident. Growing up, I was constantly involved in various activities related to this transformation, from redecorating and redesigning to rechoreographing the movements of the rides. Later I engaged in a dialogue with these experiences during my BA- and MA-level design studies, finally culminating in a speculative architectural and design proposal for the renovation of the park I had grown up in. This paved the way for my CEO career – I took over my father’s position.

Julijonas – the boy with the blue shirt – riding the Soviet amusement ride “Cabin-boy” in the Klaipeda Park of Culture and Recreation, Lithuania, 1990 (Photo taken from Julijonas’ family album)

Julijonas – the boy with the blue shirt – riding the Soviet amusement ride “Cabin-boy” in the Klaipeda Park of Culture and Recreation, Lithuania, 1990 (Photo taken from Julijonas’ family album)

But it was only quite recently that I realised it had been a little professional misfortune: I never liked to ride the rides myself, but rather preferred to wonder about those peculiar phenomena. My disinterest in submitting my body to the funfair machinery perhaps lies in the fact that I’m quite motion-sickness-prone, and that I grew up in a very standardised park (most children at that age were dreaming about Disneyland). Thus, I’ve been intimately connected to the amusement park, but also retained a substantial or, better put, critical distance. Nonetheless, in spite of (or thanks to) the latter, I felt something extremely powerful was lurking in the park. And I soon realised, that, for instance, it was the only existing hybrid narrative form that engaged or immersed its audience through virtually all the possible channels at once: psychologically, symbolically, ideologically, bodily, etc. Most interestingly, I found that this sort of surrogate reality provided a variety of aesthetic kinetic bodily-perceived experiences that was unparalleled by any other existing place, except for, was perhaps, only astronaut training camps. So, now I can say that by engineering and designing efficient ways of twisting the rider’s guts and elegantly disorienting people, I was in fact working on what I call the aesthetics of ‘gravitational theatre’ in my PhD research project.

The same model of the “Cabin-boy” ride (upper top) decorated with a red star in the Soviet amusement park “Victory” in Tiraspol, Moldova (note that such parks were usually called Park of Culture and Recreation or “Парк Культуры и отдыха” in russian.) Photo: Alexander Banekiy, 2011

The same model of the “Cabin-boy” ride (upper top) decorated with a red star in the Soviet amusement park “Victory” in Tiraspol, Moldova (note that such parks were usually called Park of Culture and Recreation or “Парк Культуры и отдыха” in russian.) Photo: Alexander Banekiy, 2011

A modernised post-Soviet version of the “Cabin-boy” in Orenburg, Russia. It is basically an old iron-rich model dressed in a shiny plastic simulacrum. Photo: Alexander Sablin, 2008

A modernised post-Soviet version of the “Cabin-boy” in Orenburg, Russia. It is basically an old iron-rich model dressed in a shiny plastic simulacrum. Photo: Alexander Sablin, 2008

The Euthanasia Coaster, a model of which is currently exhibited at the Science Gallery in Dublin, is designed to put an end to a state of boredom we might feel in the future due to an almost excessive longevity. It would allow people to leave life in a euphoric state through an amusement park ride. Why call it Euthanasia and not suicide coaster?

Have you thought of applying your knowledge of amusement park designs to other purposes?

At first, what was designed was just a fatal falling trajectory with no purpose but one: to kill the rider pleasantly and elegantly. That was where the title came from – “euthanasia” means “easy or good death” in Greek. It was a design thought experiment concerned with what the ultimate roller coaster would look like and what possible usages it would be open to. Later on, having received lots of feedback from my scientific advisers and the public, I began to add more trajectories, yet this time not as engineered curvatures but rather as storylines suggesting different uses. The key ones were obviously assisted suicide and execution. It is because the coaster may provide not just a pleasant death in terms of physiological pleasure but also, more importantly, an alternative death ritual appealing to both the individual and the mourning public.

Today, the procedures of terminating the patient’s life are highly hospitalised and not much different from a mundane injection of medicine. There is no special ritual, nor is death given special meaning, except that of legal procedures and psychological preparation. It appears that death is being divorced from our cultural life much like death rituals are dissapearing in our secular and postmodern Western society. But if euthanasia is already legal in some countries, why not make it more meaningful, not in a way certain aboriginals mourn a deceased by ecstatic singing and dancing around a bonfire, for example, but rather as a ritual adapted to the contemporary world where theme and amusement parks replace churches and shrines or at least achieve an equal power of producing spiritual effects (more and more people attend theme parks for self-improvement purposes: relaxation, self-cultivation, socialisation). This is, of course, food for thought.

It has been observed that the jumpers, people who commit suicide by falling to the ground, often demonstrate some sort of aesthetic preference for a nice place or structure to kill themselves, for example, by travelling long distances for that, but also performing some forms of rituals such as folding their clothes neatly before the jump or holding a hat on the head with both hands all the way down. What’s more, sometimes the jumpers fall undressed or perform some choreography – it seems that they care about how their bodies meet the air. All this testifies that self-murderers are not apathetic in relation to the ritual of killing themselves, and seek some sort of aesthetic meaning in it.

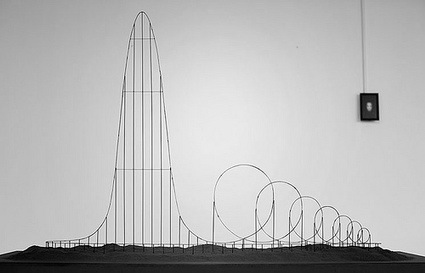

The Euthanasia Coaster scale model on display at the HUMAN+ exhibition in the Science Gallery, Dublin in April 2011. Photo: Patrick Bolger/Science Gallery

The Euthanasia Coaster scale model on display at the HUMAN+ exhibition in the Science Gallery, Dublin in April 2011. Photo: Patrick Bolger/Science Gallery

In fact, falling is a unique experience that sets itself apart from other types of death: while rushing towards the ground or, in the case of the Euthanasia Coaster, towards the loop, knowing and anticipating with the whole body the exact time of death, there is still a fraction of time for reflection. Its real-time interface and inherent dramatic structure – the leap, the fall, the impact – a three act tragedy, are not present in lethal injection, shooting yourself or in overdosing on drugs, for example. Pull the trigger and you receive the shot – there is no gap between the act and its result, while with lethal injection or overdose there is an unknown time interval. In the Euthanasia Coaster the ritualistic drama is exaggerated even more: there is a lift up the tower, the drop, the serpentine fall, the vertiginous and euphoric entry to a series of the loops, and, eventually the fatal ride within the loop. Moreover, another unique thing is that this dramatic spectacle is open to the public, be it the relatives of the rider or the victims of the sentenced to capital punishment, revealing the full drama of their demise. Given all that, the coaster incorporates the private and public aesthetics of a humane and meaningful death: for the faller it is a painless, whole-body engaging and ritualised death machine, for the observers – a monumental mourning machine.

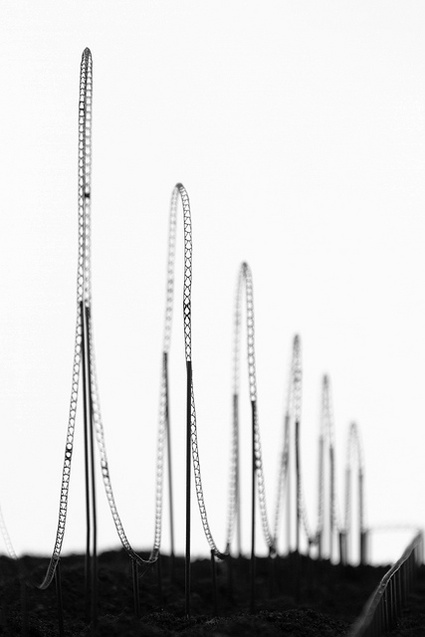

Close-ups of the scale model. Photo: Aistė Valiūtė & Daumantas Plechavičius

Close-ups of the scale model. Photo: Aistė Valiūtė & Daumantas Plechavičius

Close-ups of the scale model. Photo: Aistė Valiūtė & Daumantas Plechavičius

Close-ups of the scale model. Photo: Aistė Valiūtė & Daumantas Plechavičius

Another possible usage of the coaster – a “hacked” thrill ride – was suggested by an aeronautic engineer who happened to visit the coaster’s scale model during one exhibition in London. “Your machine could be easily hacked, you know,” she commented. Noticing my confused face, she continued: “Using anti-g-trousers that prevent pilots from blackout and fainting, I believe, I would survive the ride and turn it into the most extreme thrill ride.”

My previous project Emancipation Kit is also a part of my PhD studies and has something to do with parks as well. It is a set of specially designed tools for facilitating vomiting – a sort of vomit simulator. The project evolved out of the sketchy idea of “Vomit Park,” a park with no kinetic experiences but retaining the very result of them, puking. You visit such a vomit park, disgorge the contents of your stomach, and leave light and emancipated.

I have many more ideas of similar ‘amusements’, but most of them have to be open for bodily participation and therefore are quite pricey to build. It might take a good while until I realize them.

![Emancipation_Kit_neon_[705x510].jpg](http://www.we-make-money-not-art.com/wow/Emancipation_Kit_neon_%5B705x510%5D.jpg) Photography: Aistė Valiūtė and Daumantas Plechavičius. Neon design/typography: Egidijus Praspaliauskas

Photography: Aistė Valiūtė and Daumantas Plechavičius. Neon design/typography: Egidijus Praspaliauskas

The description of the project explains that the Euthanasia Coaster benefits from ‘the marriage of the advanced cross-disciplinary research in space medicine, mechanical engineering, material technologies and, of course, gravity.’ Could you give us more details about the technology involved in the Euthanasia Coaster?

The key technology of the coaster is basically its falling trajectory, the “story-line” of the ride, if you can call it technology. The very experience of the ride depends on the curvature of the track, and therefore all the design and engineering involved in building a roller coaster is basically structured around this linear element: its play with gravitational forces, the resulting effects on the rider’s body, dynamic loads on the supporting architectural structure, the physics of the ride such as tendency to slow down due to air drag and friction, etc.

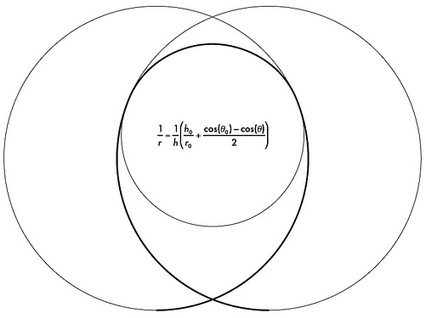

In the Euthanasia Coaster, the track incorporates both the functional and the aesthetic aspects of the ride. Both converge in the human-gravity interface design, or what I call g-design, and permeate the personal and public levels of aesthetics, dealing with the bodily experiences of the ride including pleasurable death, the ritual, but also the sculptural appeal of the coaster’s construction. Based on physics calculations, the coaster’s track has a laconic shape and is completely functional in terms of elegantly and pleasurably terminating the life of the rider. It consists of two core parts: (1) the drop tower – for dropping the coaster’s vehicle down the track to achieve such kinetic energy that allows to sustain 10 g for about a minute within (2) a series of seven teardrop-shaped vertical loop elements, arranged in a decreasing size order and forming a spiral. In order to keep constant force, the size of the lethal loops decreases along the course according to the car’s decreasing velocity reduced by the friction and air drag. The drop-hill features a heart-line roll element, a whirling coaster track element, where your heart stays roughly in line with the centre of the falling trajectory around which you body spins. This element adds a vertiginous experience, but also works as a sort of disorienting anaesthetic for the further harsher part of the ride. The latter incorporates GLOC (G-force induced Loss Of Consciousness) and brain death caused by cerebral hypoxia, oxygen deprivation in the brain- which is, curiously, usually a euphoric experience accompanied with surreal dreamlets.

The Euthanasia Coaster’s loops are specially engineered in the shape of a clothoid loop to sustain uniform and constant g-forces along the ride. Specifically, it sustains 10 g which is not too much to get injured physically and not too little to come back alive.

To calculate all the physics, I needed some mechanical characteristics of the vehicle. For this I modelled a hypothetical vehicle with rough physics approximations of 1 ton roller coaster car with no windshield (I wanted the passenger to feel the wind, its increasing force, and, eventually, terminal velocity).

A prototype of the vehicle of the Euthanasia Coaster by Julijonas Urbonas, 2010

A prototype of the vehicle of the Euthanasia Coaster by Julijonas Urbonas, 2010

When it comes to efficiency, the coaster is in fact not the best solution to end one’s life with g-forces, as there are more efficient ways of killing people such as the human centrifuge, the Euthanasia Coaster’s closest analogue, or many killing machines and techniques introduced by the Nazis. In comparison to those, the coaster is extremely bulky and grandiose, but this heaviness is balanced by the aesthetics of experiential, functional and sculptural lightness devoted to the dignified death of a human being. Moreover, it is also ‘light’ for the earth as the coaster is driven almost solely by gravity.

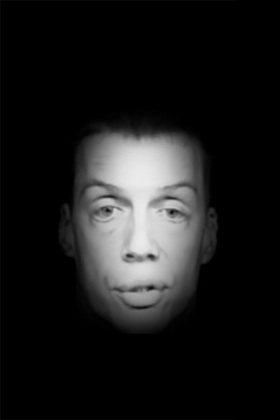

The model is exhibited at the Science Gallery along with a b&w video showing the face of -i think- a pilot. There’s a short extract in this video.

Could you describe what the man in the video is experiencing?

The pilot in the video is undertaking high-g training in a U.S. Air Force Centrifuge at Brooks Air Force Base, Texas. He is performing a set of anti-g-strain manoeuvres – special techniques of breathing and muscle contractions of lower extremities, especially in the abdomen and legs to keep blood circulating in the upper part of the body – which prevent one from fainting while performing high acceleration turns (an experiential equivalent of the Euthanasia Coaster’s loops). The pilot there is spun around at approx. 9 g, which means he experiences a nine-fold increase in his body weight. He is stuck to the seat so hard that his whole body is almost completely immobilised. You can see in the video the tissues of his face drooping down – it looks like he is ageing remarkably. Breathing requires more effort, as the ribs and the rest of the internal organs are pulled down, which empties air from the lungs. The force rushes the blood to the lower extremities of the body, thereby causing oxygen deficiency in the brain, which results into blurred colourless vision (aka greyout), later – loss of peripheral sight (aka tunnel vision) and hearing, and blackout. Eventually, this experience – accompanied by disorientation, anxiety, confusion and even euphoria – is crowned with G-LOC, during which the body is completely limp, and vivid bizarre dreams occur, such as being in a maze and unable to get out, or floating in a white space, not knowing who you are, why you are here, etc (check this video). While the pilot is recovering from G-LOC, he is still unconscious, his body flails around in a chaotic fit that is called “funky chicken” in aeromedical slang, as the neurons in the brain – replenished with extra oxygenated blood pumped harder from the heart – begin firing once again. This causes arms and legs to twitch uncontrollably. After having lost consciousness in centrifuge training, pilots often experience amnesia and deny the fact they lost consciousness, even feel dumbfounded when shown video tapes of the episode.

The pilot in the video is undertaking high-g training in a U.S. Air Force Centrifuge at Brooks Air Force Base, Texas. He is performing a set of anti-g-strain manoeuvres – special techniques of breathing and muscle contractions of lower extremities, especially in the abdomen and legs to keep blood circulating in the upper part of the body – which prevent one from fainting while performing high acceleration turns (an experiential equivalent of the Euthanasia Coaster’s loops). The pilot there is spun around at approx. 9 g, which means he experiences a nine-fold increase in his body weight. He is stuck to the seat so hard that his whole body is almost completely immobilised. You can see in the video the tissues of his face drooping down – it looks like he is ageing remarkably. Breathing requires more effort, as the ribs and the rest of the internal organs are pulled down, which empties air from the lungs. The force rushes the blood to the lower extremities of the body, thereby causing oxygen deficiency in the brain, which results into blurred colourless vision (aka greyout), later – loss of peripheral sight (aka tunnel vision) and hearing, and blackout. Eventually, this experience – accompanied by disorientation, anxiety, confusion and even euphoria – is crowned with G-LOC, during which the body is completely limp, and vivid bizarre dreams occur, such as being in a maze and unable to get out, or floating in a white space, not knowing who you are, why you are here, etc (check this video). While the pilot is recovering from G-LOC, he is still unconscious, his body flails around in a chaotic fit that is called “funky chicken” in aeromedical slang, as the neurons in the brain – replenished with extra oxygenated blood pumped harder from the heart – begin firing once again. This causes arms and legs to twitch uncontrollably. After having lost consciousness in centrifuge training, pilots often experience amnesia and deny the fact they lost consciousness, even feel dumbfounded when shown video tapes of the episode.

If i understood well, the Euthanasia Coaster is part of a PhD research project that explores gravity’s impact on creative disciplines such as design but also art and architecture. Has this field of Gravitational Aesthetics been really so under-explored so far? What will the rest of your “Gravitational Aesthetics” investigation be about? Are you working on other prototypes?

The study “Gravitational Aesthetics” – both theoretical and studio-based – is original on several levels: the systematic phenomenological (or experiential) survey of gravitational experiences such as amusement rides, various levitations, even lucid weightless dreams; and the development of a specific design approach, g-design (the prefix “g” stands as a conceptual link to g-force or gravitational force).

G-design, a marriage of gravity and design, is an original creative and critical approach examining the complexity of the cross-interactions between gravity, aesthetics, technologies and philosophy. Inspired by amusement rides and choreography, it invokes the powerful gravity’s creative potential for creating revelatory and enriching experiences that engage the whole body and imagination. Choreographing the bodies through design, shaking the body’s innards with poetic vehicles, imagining alternative gravities are a few things that g-design is concerned with.

You may say this approach is not new – there are individual examples of artistic, design, architectural, engineering work that might be ‘labelled’ as g-design. For instance, roller coasters designed by Harry G. Traver, custom-modified wingsuits, the oblique architecture of Paul Virilio, imaginary vehicles by Panamarenko, etc. These examples abound, yet they are fragmentary, and there is no person who has/had pursued an extensive and systematic study in this area. G-design aspires to fill this gap by surveying the existing examples and designing new ones, while striving to unify and synthesise them in a single theory or creative approach, and give it pragmatic orientation, something that an individual can directly translate into or apply to an artistic practice.

The research project has been mainly theoretical so far, but in parallel to writing I’ve been sketching all the time, and have produced quite a bunch of ideas that I am very enthusiastic about putting into practice now. Currently I’m developing a few ideas of conceptual amusement rides open to bodily submission: one involves collaboration with a choreographer and roboticist, another has to do with imaginary exercises.

A performative lecture on the experiential reality of levitation, was delivered at the Arts Catalyst, London, June 2011. Photo: Aistė Valiūtė and Daumantas Plechavičius

A performative lecture on the experiential reality of levitation, was delivered at the Arts Catalyst, London, June 2011. Photo: Aistė Valiūtė and Daumantas Plechavičius

Thanks Julijonas!

P.S. Julijonas Urbonas also invites musicians, sound artists and engineers to submit sound compositions for a series of the installations “Sounding Doors.” Selected compositions will be played by opening/closing a door augmented with specially integrated electronics in various public locations in the city Karlsruhe in late Summer. DEADLINE: 1 August 2011.

Check out The Euthanasia Coaster (as well as Reproductive Futures and the Center for PostNatural History) at HUMAN+, an exhibition on view through June 24, 2011 at the Science Gallery in Dublin.