“How do we narrate extreme violence without succumbing to its necropolitical impact? “How do we make the invisible visible? The unheard audible?” “What aesthetic investigative research strategy do creators from Latin America and other post-colonial environments develop to talk about experiences of violence?” And, in the context of the spiral of violence that Mexico is now experiencing, “What ethical and artistic challenges do we face?”, “How do these artistic practices intervene in the social imagination?” “What kind of counter-knowledge do we produce as artists during this process?” Those are the kind of questions that Luz María Sánchez explores in her work.

Luz María Sánchez. Photo: Fabio Perletta

Luz María Sánchez. Photo: Leandro Pisano

Speaking in the beautiful Gardens of Palazzo Ducale of San Martino Valle Caudina for the Interferenze festival a few weeks ago, the artist and scholar explained how she uses sound to convey narratives, violence and emotions that words cannot express on their own. The issues her practice explores are hard-hitting: innocent civilians caught in the line of fire, deaths while crossing borders, forced disappearances, militarisation of public space, silence as a survival strategy and other acts of violence experienced by people whose daily life is affected by narco brutality.

Her practice uses sound to make emerge the horror of daily violence. Not to cause distress but to help build empathy and contribute to exposing crimes that traditional Mexican media often fail to cover for fear of being directly targeted by drug traffickers.

Luz María Sánchez‘ work has a transdisciplinary approach. She often develops her work in collaboration with experts in social sciences, transitional justice, engineers, programmers, biologists, etc.

The works she presented at the Interferenze festival are inspired by some regions in Mexico where violence is normalised. She was particularly interested in investigating and showing how the civil population survives situations of extreme violence in the context of a failed state. The violence experienced by people who attempt to emigrate. Or the violence experienced on a daily basis by those who remain and try to survive in the narco-state.

Luz María Sánchez, 2487*, 2006. Photo: FOR-SITE Foundation

The work 2487* speaks the names of the two thousand four hundred eighty-seven people who died crossing the Mexico-U.S. border. The research was done in 2006 and the number is much higher today. The generative sound piece is played on 16 loudspeakers. It is accompanied by a book containing the information collected about each of the bodies found crossing the border. The work takes a special resonance in the US where families who arrived recently or a few generations ago in the country have an opportunity to think of the increasingly dangerous journey undertaken by their relatives to arrive in the USA.

While living in the South of Texas, Sánchez developed Rio Grande Rio Bravo. The 8-channel sound installation reproduces the sounds of the big river that draws a line between Mexico and the United States. Visitors find themselves surrounded by 8 speakers that stream a soundscape of peaceful, natural river noises until border patrol sirens suddenly break the harmony of the sounds. There is so much surveillance and sensing technology on the US-side of the riverbank that if you walk by the river, a patrol car immediately arrives. Furthermore, Border Patrol also park their vehicles to be visible to families on the Mexican side. Mexicans can see them and hear sirens telling them they are being watched. The threat is omnipresent, even to those who are not part of the group who risk their lives to cross the border.

The siren transmits the sensory moments of violence felt by those living near the U.S.-Mexico borderlands.

V.[u]nf_1, plastic model. Photo via unlikely

Luz María Sánchez, V.[u]nf_1.01 introductory video

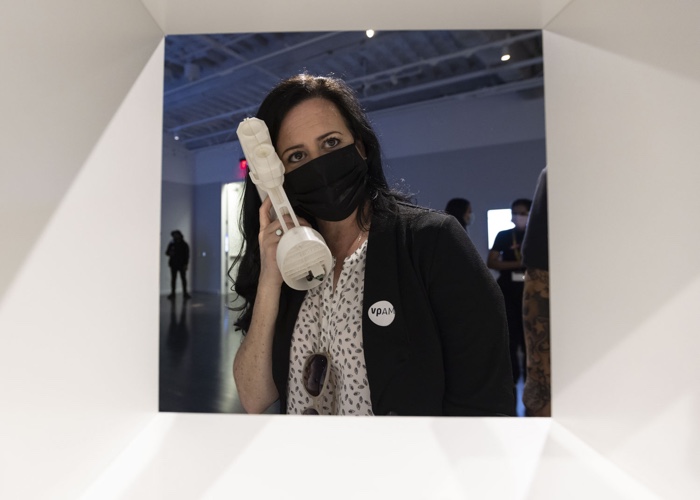

Luz María Sánchez, V. [u]nf_1.01, 2022. At the Vincent Price Art Museum. Photo by Monica Orozco

Luz María Sánchez, V. [u]nf_1.01, 2022. At the Vincent Price Art Museum. Photo by Monica Orozco

Luz María Sánchez, V. [u]nf_1.01, 2022. At the Vincent Price Art Museum. Photo by Monica Orozco

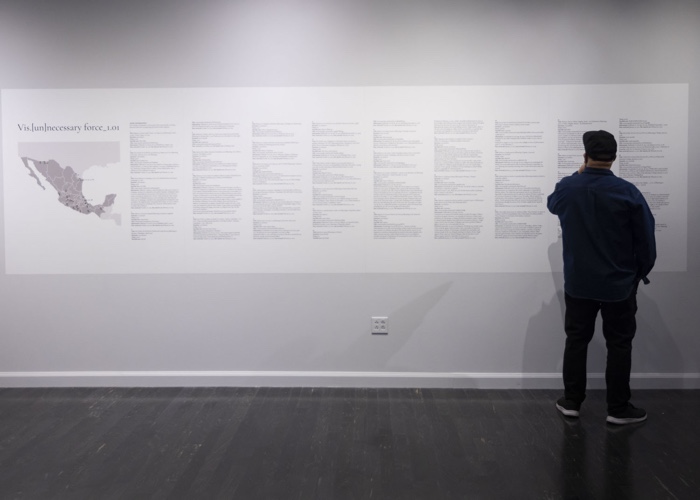

Vis. [un]necessary force, aka V.[u]nf, is an ongoing research project that explores the ways in which the civilian population survives in contexts of extreme violence exerted by legitimate and illegitimate power groups.

V. [u]nf_1.01, the first iteration of the project, deals with citizens doing journalism to make up for the media censorship around drug-related violence. In 2006, President Felipe Calderón declared the war on drugs. His strategy consisted in deploying the military in civilian positions. Suddenly, people found themselves surrounded by soldiers who are not trained to deal with normal life. The militarisation of civilian space didn’t improve the situation. To this day, more than 100,000 people (and counting) have been reported as disappeared in Mexico. Most of them vanished after the launch of Calderón’s “war on drugs”.

Sanchez explained that, when he realised that he was losing the battle against the cartels, Calderón asked the media to stop reporting on it. Some of the major media accepted. Civilians stepped in and started doing their own reporting to inform others about what was going on in their own communities. Many journalists and citizen journalists are still being killed either by the police or by the drug cartels today.

V. [u]nf_1.01 brings together a selection of sounds recorded by citizens on their mobile phones when they were trapped in the middle of shootings in their streets, at the office, in their house…. After the shootings, the citizens uploaded the video on YouTube. Sanchez selected videos shot by civilians and streamed their sounds into loudspeakers she found in a Mexico City market. These loudspeakers, made of black plastic and usually bought by people to play music in living rooms, look exactly like 9 mm guns. Each of them is loaded with a unique audio clip.

In further installations of the work, the artist used guns made in her own studio. They are now white. The violence is still there but more subtle and ambiguous. In order to play the sound, visitors have to grab the gun and activate the “weapon”. This type of interaction gives the audience the option to listen to the sound file. It is not imposed upon them. The piece is accompanied by textual information about each track (its origin, author, etc.) On one of the walls is a map showing that this type of situation can happen anywhere in the country. Visual elements play an important role in Sánchez’s work to get the public engaged: “We don’t hear with our eyes closed,” she explained.

The found recordings break the silence created by narco criminality in Mexico, a country where not talking or writing has become a survival skill. These soundtracks reveal the horror of experiencing violence at a very close range and the bravery of those who decide to document and share what it means to be caught in the crossfire of a drug war clash. You can listen to the sound archive online.

The first selection for the piece was made in 2014 which was also the year of the Iguala mass kidnapping. 43 Mexican students were ambushed and made to disappear. Their bodies have never been found. Parents are still looking for their daughters and sons. Before the idea of the Noche de Iguala even emerged in the press, two videos recorded by citizens during that shooting in Iguala had already appeared online.

Luz María Sánchez, Vis. [Un]necessary force_4 (V.[u]nf_4), 2018-2019. Photo via

Luz María Sánchez, Vis. [Un]necessary force_4 (V.[u]nf_4), 2018-2019. Photo via

Luz María Sánchez, Vis. [Un]necessary force_4 (V.[u]nf_4), 2018-2019. Exhibition view

Sanchez developed the 4th version of the work, Vis. [Un]necessary force_4 (V.[u]nf_4), in collaboration with a group of women called Las Rastreadoras de El Fuerte, in Los Mochis, a coastal city in northern Sinaloa, Mexico. Because the country is trapped in a cycle of violence and impunity, civil society has to compensate for the failure of authorities and organise independent searches for “clandestine graves”. The artist made a phone app for the women to record themselves as they search for victims of forced disappearances. The women go out into the desert of Las Moches, they search and dig to find the bodies of their children. The sound installation enables visitors to listen to the day-to-day exchanges between the Rastreadoras while they are looking for their kids. We hear the ambient sound, footsteps and the noise of the tools digging in the middle of the desert, we hear disappointment and silence but we can also hear the jokes these mothers share as a way to cope, survive and express solidarity with each other.

Luz Maria Sánchez and curator Leandro Pisano, Interferenze festival 2022 talk session #2, Palazzo Ducale, San Martino Valle Caudina

More information in the article that Luz María Sánchez wrote for Australian journal Unlikely.

Related stories: Sound art, Ecology and Auditory culture. Lisboa Soa 2016-2020; The Manifesto of Rural Futurism; Two Sides of the Border. The region that Mexico and the US share; No Lone Zone; The pavilion i wish i hadn’t missed at the Venice Biennale, Lyon Biennale – Pedro Reyes, etc.