Seed varieties have declined significantly since the beginning of time. First, with plant domestication and now, increasingly, through homogenization, industrialisation, privatization and commodification of our seed stock. Independent groups are currently working as private protectors of genetic diversity by cultivating endangered varieties in their home gardens, sharing seeds with other seed savers, but also lobbying the EU to make sure that a new proposal for seed marketing regulation will promote agricultural biodiversity, small-farmers’ rights, global food security and consumer choices.

Flatbread Society Soil Procession, 2016. Photo by Monica Loevdahl

Futurefarmers Seed Journey, 2016. Photo: Nina Sahrauoi

The need for a robust and vibrant culture of seed diversity was one of the motivations that led Amy Franceschini and Futurefarmers to establish the Flatbread Society – a collective of farmers, artists, activists, scientists and other people involved in urban food production and preservation of the commons. Since 2012, the group have been working in a permanent “common” area on the waterfront development of Bjørvika in Olso, Norway. They built an urban farm, an allotment community, an ancient grain field and a bakehouse.

Last year, however, a delegation of the Flatbread Society embarked on a year-long sailing expedition that will take them from Oslo to Istanbul. On board is a rotating crew of artists, sailors, anthropologists, activists, writers, ecologists, etc. As for the cargo, it consists mostly of grain seeds that had been lost or forgotten.

Along their journey to the Middle East, where the cultivated grains originated, the members of the crew stop in harbours to meet artisan bakers and farmers, make flatbread, collect and exchange seeds but also document and retrace the journey that the seeds made thousands of years ago.

Artes Mundi 7: Amy Franceschini, founder of Futurefarmers explains the Seed Journey. Video Artes Mundi

I talked with Amy Franceschini a few weeks ago about the Flatbread Society’s extraordinary sailing adventure and about their efforts to raise awareness around the need for the development of plant genetic diversity.

Flatbread Society, 2016. Photo by Monica Loevdahl

Flatbread Society, 2016. Photo by Monica Loevdahl

Hi Amy! First of all, I’m quite curious about the seeds you’ve decided to take on this ‘reverse journey’ to Turkey. Which varieties of grains did you select exactly?

We started with a Finnish Rye. We came to this rye when searching for someone farming “ancient” grains in Oslo. We have been working on a public artwork in the former port of Oslo for the last 5 years. The center piece of this work is a grain field featuring ancient grains that have been rescued from interesting places.

For example, this Finnish Rye was found between two boards in an old sauna used by the Forest Finns in the early 1900’s to dry their grains.

This grain was thought to be lost, but an amateur archaeologist rediscovered it.

Our project in Oslo is located on a “commons” – a piece of land set aside within this waterfront development that should be accessible to all. We took the tradition of Norwegian commons to heart in this project and wanted these ancient grains to symbolize the biological commons which is currently at risk due to the privatization and commodification of our seed stock.

“The return of ancient seeds is like reverse engineering, taking apart this long history fold-by-fold. This voyage is an allegory, one forever open to chance. Our participation from afar breathes wind into the sails of the future”

– Michael Taussig, Seed Journey on-board ethnographer.

Flatbread Society Seed Collection, 2014. Photo: Futurefarmers

And why did you chose to travel with these particular seeds?

Each of these seeds have a particular story of rescue associated with them. And through the planting and exchanging of them comes an awakening. For example, a variety of barley that we have with us came by way of St. Petersburg. Nikolai Vavilov collected more seeds from around the world than any other person in history. He was one of the first scientists to really listen to traditional farmers, peasant farmers — and ask why they felt seed diversity was important in their fields. During the siege of Leningrad in 1941, Vavilov was imprisoned by Stalin where he starved to death. He became the main opponent of Stalin’s favored scientist Trofim Lysenko for his defense of Mendelian theory. Just a few blocks away in the Vavilov Research Institute of Plant Industry, Vavilov’s staff scientists locked themselves in the seed bank to diligently protect his seeds. Over half a million people starved to death during the 28 month siege while these twelve scientists filled their pockets with grains so that future generations would be able to grow food. When the allied troops arrived at the seed bank they found the emaciated bodies of the botanists lying next to untouched sacks of wheat and other edible seeds -a genetic legacy for which they paid with their lives.

Futurefarmers Seed Ceremony, 2017. Photo: Mads Hårstad Pålsrud

Futurefarmers Seed Ceremony, 2017. Photo: Mads Hårstad Pålsrud

Futurefarmers Seed Ceremony, 2017. Photo: Mads Hårstad Pålsrud

Another wheat we have is called Brueghel. During an archaeological dig in a church in Pajottenland, Belgium, charred rye and wheat seeds were found. The archaeologists and a group of local farmers call these found seeds Bruegelseeds because they date from the time of Bruegel, the old Belgian painter known for landscapes and peasant scenes.

A group of young farmers want to make a “BruegelBread”, a bread made in the landscape of Bruegel. For the moment all of the grain for human consumption in this region comes from abroad and they would like to reinstall a local chain from the ‘Bruegelseed’ to the ‘Bruegelbread’.

This April 1st, we summon this ancient Brueghel grain and imagine what Bruegel would paint or make in 2017. Futurefarmers will host a Seed Ceremony at the Heetveldemolen – Heetveld Windmill. On this day many farmers will gather to share their unique and local cultivated grains. A handful of Brueghel grain will be launched onto the Futurefarmers Canoe Oven and rowed from canal, river and into the Schelde to Christiania.

Flatbread Society, Futurefarmers’ Canoe Oven, 2013. Photo: Max McClure

This journey to the Middle East can be seen as an awakening of the memory—the long journey the grain itself has taken—through the hands of time.

— Michael Taussig, Now Let Us Praise Famous Seeds

Will you be collecting other seeds along the way?

Yes. Collect, share, collect.

We collect and share at each stop. We carry a small wooden boat that holds all of the seeds we collect.

Our mothership RS10 Christiania carries an ingeniously crafted mini-boat “like a chalice.” Containing small amounts of old wheat and rye seeds collected along the journey.

These seeds are like jewels. The disproportion in size between the small chalice and the mother vessel carrying it symbolizes preciousness as does the very idea of a prolonged voyage using wind and sail as the means of propulsion.

– Michael Taussig, Let Us Now Praise Famous Seeds

The mini boat of RS10 Christiania. Photo by Monica Loevdahl

The mini boat of RS10 Christiania. Photo by Monica Loevdahl

What do you mean when you say that the seeds have been ‘rescued’? Rescued from what or whom? And how? To what purpose?

The latin root of the word “rescue” is to return.

The seeds we choose to carry with us are seeds that were either lost or fell out of production and then found again, like the stories I referred to earlier, or they are seeds that farmers have gotten out of gene banks that have not been grown for 30-80 years. These farmers are working to return these seeds to the ground and into production rather than sitting dormant in gene banks.

The seeds they are growing fell out of production before the green revolution, so they have not been homogenized. But if they are not grown each year as a landrace, they do not have the opportunity to adapt to their local growing environment; soil, weather and social desire – taste.

Our collaborator in Norway is very busy collecting grains out of gene banks and getting them into the ground. He says,

“We don’t need a museum to conserve varieties, what we want is to grow them. “

-Johan Swärd, Norwegian farmer, Brandbu

It is truly our only hope for shifting from the dominant agricultural framework to a smaller, more local scale production of food.

Flatbread Society, 2016. Photo by Monica Loevdahl

Flatbread Society, 2016. Photo by Monica Loevdahl

Flatbread Society (Baking workshop), 2016. Photo by Monica Loevdahl

Why is this important to use heritage grains?

Agribusiness supplanted locally adapted seeds with fewer varieties of seeds: until the late 19th century, most plants existed as highly heterogeneous landraces. Over the past century of modern breeding, attempts to produce cultivars that meet the advanced agriculture demands of an increasing population has resulted in the landraces being almost wholly displaced by genetically uniform cultivars. The result has been a narrowing genetic base that puts these plants and the future of food at serious risk.

And aren’t they threatened with being patented like other grains?

It is said that wheat and rye were domesticated in Kurdistan and through gift and trade not to mention wind, birds, and animals, made their way north to Europe to become the “staff of life.” These “old” seeds come loaded with an underground history at once social and biological. The domestication of plants involved a long march through trial and error, not to mention chance, whereby certain varieties became reliable foodstuff. It was a revolution in world history, ushering in what is called the Neolithic period with tremendous consequences, one of which, of course, was deforestation. Another was the birth of the state and private property. We sail along the cusp of many contradictions.

Cultivators in each and every micro-climate developed their own varieties of seed stock from their harvests to the present time when, all of a sudden, such practices have been declared illegal. Another revolution is afoot. Farmers who continue with old stocks are at risk of arrest. They too are now an endangered species. In referring to themselves as such they cement an alliance — biological and political — with the plant world, which is what Flatbread Society is doing as well.

At the moment, they are such a small market and the farmers who are bringing them back into production are not interested in profit as such, but sustainability. The ideal scenario for these seeds would be to stay small in scale in terms of production and very local, so that they are adapted to a local biotope, ecology, taste and weather. This would enable a very local, durable and resilient economy, but not one based on surplus or growth per se.

But yes, these seeds can be in danger of being collected by large companies, patented and homogenized.

For example, Tanzanian farmers are facing heavy prison sentences if they continue their traditional seed exchange.

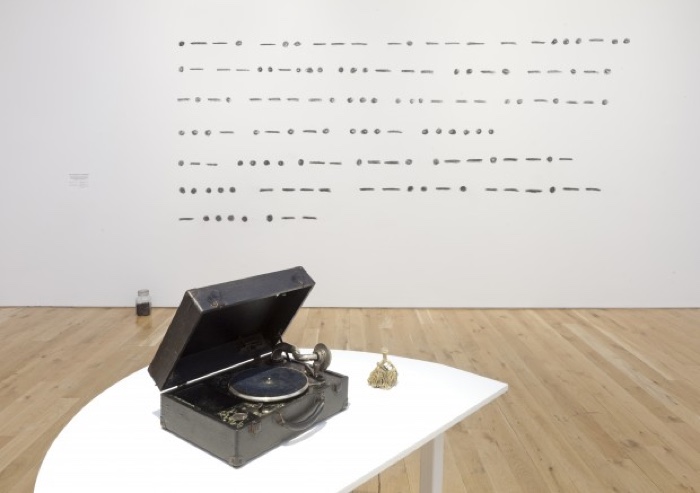

Amy Franceschini / Futurefarmers, Flatbread Society, Seed Journey, 2016 -17. Prints, charcoal drawings, video, benches, sail, canary cage and performance. Artes Mundi 7 installation view, National Museum Cardiff, 2016

Amy Franceschini / Futurefarmers, Flatbread Society, Seed Journey, 2016 -17. Prints, charcoal drawings, video, benches, sail, canary cage and performance. Artes Mundi 7 installation view, National Museum Cardiff, 2016

Ever since I’ve followed your work, I’ve been amazed by the way you connect with audiences outside of the traditional art venues. So how do you communicate this project and the issues behind it (politics of food production, role of grains in the economy, environmental challenges, knowledge sharing, etc.) to the people you encounter along the way?

We still depend on the arts institution as our main support. They are a very important amplifier of our work. They have a much wider media reach than we do. Through them, we have the capacity to bring farmers onto a cultural stage, which in some cases validates their work as seminally cultural. For example, when we exhibited at the National Museum in Cardiff for the Artes Mundi Shortlist exhibition, we were able to host a Seed Ceremony / Exchange with the Welsh Grain forum. We hosted this in the National Library inside the National Museum. Since we had access to this space our project became more legitimate and we were able to extend this legitimization to the farmers work by inviting them. The farmers work became legitimatized as a cultural practice and was documented by the BBC which gives their work a voice.

As Seed Journey moves along its route, word gets out and when we arrive in small or large harbors we are often welcomed by a small group of hosts, a town mayor, the local newspaper and passersby. We try to announce our arrival when we know the time/day of our arrival- to the mayor of small towns, align with harvest, sowing festivals, align with maritime Community. Our boat has an allure in itself, so a few times when we arrive at a marina, the harbor master is quite proud to have us and calls the local media.

For us, the message must move beyond the art venue, but the art venue is a valuable collaborator.

RS-10 Christiania, 2010. Photo: Martin Hoy

RS-10 Christiania. Photo courtesy of Futurefarmers

And then there’s the RS-10 Christiania boat! It is stunning! How did you end up with that boat?

Be careful what you wish for. The whole idea of the Seed Journey was really a very seed of an idea provoked by a day out on the Oslo fjord with Lars Hektoen, a Norwegian alternative banker. We were discussing the idea that seeds were once the first currency in many places. I proposed the idea of sailing the seeds we had been growing in Oslo back to the middle east as a way to unravel this history and theories of how these seeds migrated and how surplus seed stock availed so many aspects of “civilization”.

He immediately said, “fantastic!” If you do such a journey, you must take a Colin Archer rescue sailboat. They are safe, steady and still are a few in Norway.

Through our commissioner in Oslo, a meeting was set up with the Petersen brothers, the owners of RS 10 Christiania (Rescue Sailboat Christiania). A mutual excitement about the project emerged and an agreement was made to sail her and our seeds to Istanbul.

The boat is a beautiful thread of our story. She is a slow and steady craft. You can feel her line of duty as she sails us towards the unknown.

She is also the most expensive part of our journey, which has proven to be a challenge and might force us to abandon ship in Leg 2 and transfer to another vessel. But we will be launching a Kickstarter campaign in mid-May to try to keep her and the Petersen’s with us. But if you already would like to donate, our homepage is accepting donations.

A side note, Christiania sunk in the north sea in 1995 – also a point of reference to rescue.

Flatbread Society Bakehouse, Oslo, Norway, 2016. Photo: Monica Loevdahl

Is there anything in its story or design that particularly connects with the Flatbread Society/Seed Journey project?

Flatbread Society is a durational public art project in Oslo Norway which includes a Grain field, a Bakehouse and 10 years + of artistic programing. The grainfield connects Norway’s agricultural heritage to the present, extending the metaphor of cultivation to larger ideas of self-determination and the foregrounding of organic processes in the development of land use, social relations, and cultural forms. The presence of this grainfield against the backdrop of the city of Oslo and the Barcode — its openness and fluidity — stand in stark contrast, culturally and physically, to the rational and rigid development in the surrounding areas of Oslo.

In 2015 a group of 75 people, swarms of bees and a colony of airborne and soil-based microorganisms gathered in a geo-location now called Losæter — a museum without walls where an expanding inventory of ancient grains are growing.

Since then, a selection of seven grains have been planted upon this new common area in Oslo. Each variety has been “rescued” from various locations in the Northern Hemisphere — from the very formal (seeds saved during the Siege of Leningrad from the Vavilov Institute seed bank) to the informal (experimental archaeologists discovering Finnish Rye between two wooden boards in an abandoned sauna in Hamar, Norway). Together with local farmers Johan Swård and Anders Naes, these seeds and the knowledge of how to grow, harvest, mill and bake them have become embedded in the project.

Horse plough in Losæter. Photo by Vibeke Hermanrud

Could you tell us a few words about the people who accompany you on this journey? What is their role and how did you select them?

The project inherited an imaginary early on. Each time we speak of this journey, it fills ones mind with joy, hope, and wonder as well as being viewed as a critical project that needs to be happening right now. There is an absurdity and persistence to the project that captures people.

Many people enlisted themselves and soon enough we had an incredible crew of artists, anthropologists, ecologists, farmers and sailors. The core crew was born out of a conversation in Gent, Belgium over two years ago whereby, we asked each other, “If you had to be on a boat with this mission, who would need to be on this journey?” At this point it was more of a fantasy, but we wrote down many names, and most of them are now formal crew members.

The idea is that a rotating crew of artists, scientists, writers and farmers research

interests influence the journey, but the grains ultimately guide the route. Seed Journey maps not only space, but also time and phylogeny: while the more familiar space yields a cartographic map, time yields history and phylogeny yields a picture of networks of relationships between and among living beings —relationships between cultural groups, but also between human and non-human living forms such as seeds, sea-life and the terrestrial species from the various places and times we will traverse.

You have travelled (or will have travelled? I don’t know where you are at the moment) from Oslo to Cardiff with the project. What will happen (or did happen) during the Cardiff stop? What did you find in Wales?

September 17, Oslo we departed with a Send Off procession from the FBS grainfield to a fleet of Colin Archer rescue boats and other smaller boats to send us off.

We headed to Cardiff via Denmark and London where we met farmers, bakers and brewers and eventually shared all of the seeds gathered with the Welsh grain forum (as described above).

On April 1, we will have a pre-send off gathering in Belgium in collaboration with Muhka and Middleheimmuseum and a host of farmers and millers from Pajottenland.

On April 18, we will formally send off from Antwerp en route to Istanbul via

Jersey Island (Morning Boat residency), San Sebastian/ Tabakalera and Santander/ Botin Foundation.

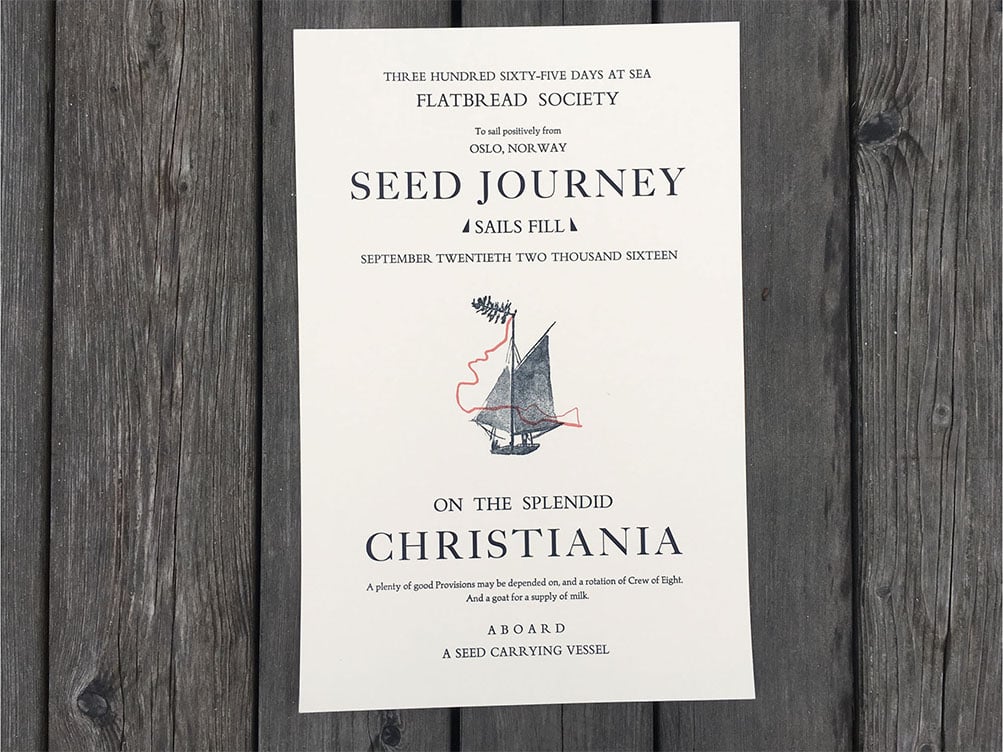

Seed Journey Broadside

What do you hope will be the impact of this reverse journey?

We try not to think in terms of “impact”. This is a work in progress and it still has a lot to tell us and to discover. We hope to protect this space without the terms of impact, outcomes etc. But of course a basic drive for the project is to raise the status of the small farmer’s work, validate this work, connect farmers in various locations so as to strengthen the network that is working to protect farmers rights and most importantly to keep the seeds in the hands of many rather than a few.

Thanks Amy!