A recent study estimated that over 20% of the videos that YouTube’s algorithm recommends to new users are AI slop. Figures like these make it hard to deny that images have lost their representational integrity.

The exhibition recently opened at the SMAk in Ghent remind us that images used to have value, reliability and political power. And most probably they still do.

Avelino Sala, 4,33 minutes of silence of minutes of silence, 2021

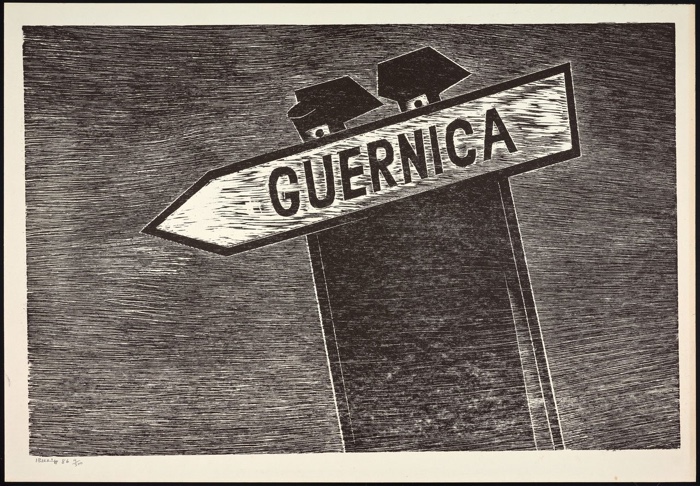

Augustin Ibarralo, Paisajes de Euskadi series, ca. 1970-1979

EUROPALIA ESPAÑA | Resistance. The Power of the Image shows how artists from Spain, from the outbreak of the Civil War (1936–1939) until today, have wielded images as tools of protest, denunciation and collective awakening. To this day, for example, Picasso’s Guernica continues to symbolise the resistance to military violence as much as it did when it was painted in 1937 in reaction to the bombing of the small Basque town by Franco’s allies, the Nazi German Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion and the Fascist Italian Aviazione Legionaria. The painting endures as forceful testament to art’s capacity to translate horror into political urgency.

Of course, the influence of images is a double-edged sword, as images can also be deployed to conceal, manipulate and control reality. Especially in an era where democracy is also under attack.

Fernando Sánchez Castillo, The Global Museum of Civil Protest, 2015-2022

Alán Carrasco, En ese claroscuro, 2021

The Power of the Image focuses on two key periods in the recent history of Spain when art was used as a tool for political dissent. The first one focuses the 1970s, the final period of resistance against Franco’s dictatorship (1939-1975), and the seemingly quiet transition from dictatorship to democracy. The second period spans the last two decades, when Spain experienced a wave of demonstrations. Beginning in 2011, when the Indignados (the indignant) protested against welfare cuts, the banking system, capitalism, politicians, public corruption and other threats to basic democratic values. Contemporary artistic practices also respond to the contested legacy of Franco’s fascist regime. While many young people challenge the historical silences and lingering traumas embedded in Spanish society, others (particularly young men) are drawn to the fetid ideas of the far-right party Vox and express nostalgia for dictatorship ideals they never actually endured.

“Ultimately, the exhibition asks viewers to confront the unresolved tensions of Europe’s shared histories: How do we visualise wounds that remain open? What meanings do they carry? How do past violences continue to mark bodies, landscapes and social relations? And perhaps most importantly, how can we imagine futures that acknowledge these histories without being bound by them?“

Here’s a selection of the works on show. With a heavy emphasis on artworks developed in the last decade:

Xavier Arenós, Teorética del pan (El pueblo español tiene un camino que conduce a una estrella), 2019

Xavier Arenós’s installation pays homage to a sculpture that Alberto Sánchez exhibited in the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris, where he, Picasso and other Spanish artists used this international platform to denounce the horrors of the Spanish Civil War (1936-39). Its title was El pueblo español tiene un camino que conduce a una estrella (The Spanish People Have a Path That Leads to a Star). Some compared the metre-high work to a giant cactus; others to the shape of a wavy field in Castilla. However, its organic shape could also evoke an elongated loaf of bread.

Arenós’s installation comprises eight sculptures that range from 1.35 to 1.75 metres in height, the average stature of the Spanish working class in the 1930s. The variations in size reflect regional food shortages. Spanish men were the shortest in Europe at the time, with an average height of 1.65 metres, while Spanish women were, on average, 10 centimetres shorter. Arenós’s installation visualises this period of malnutrition and poverty and asserts a fundamental right: the right to basic nourishment. The impact of the piece is immediate. As you walk alongside the sculptures, you realise how short people had been less than a century ago, a haunting reminder of the physical toll exacted by political oppression.

Ana García-Pineda, La Curva del Olvido [The curve of Forgetting] (film still), 2013

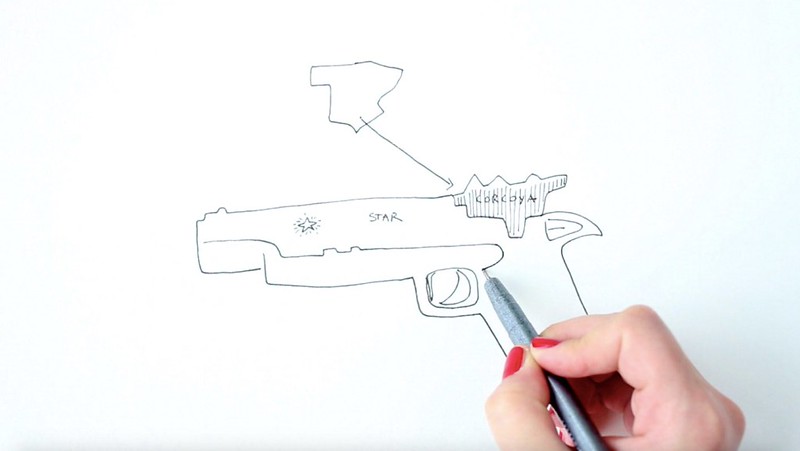

Ana García-Pineda, La Curva del Olvido [The curve of Forgetting], 2013

In La Curva del Olvido (The Curve of Oblivion), Ana García-Pineda narrates her grandmother’s life while drawing it on a white board. Her grandmother’s father, a watermelon grower in a village near Seville, became mayor simply because he was the only literate man in the community. He was murdered in 1937, when fascist forces invaded the village. García-Pineda’s grandmother’s name was Armonia, which means ‘harmony.’ However, the fascist government and the Catholic Church decided that every Spanish citizen had to be named after a saint of the official catholic calendar. It was decided that she would become Dolores, which means ‘sorrows.’ Illiterate and just thirteen years old, the grandmother left the village and found work in Barcelona with a wealthy Catalan family. Although she didn’t understand Catalan, she would listen to the stories that the nanny told the children at night. She’d learn the sounds by heart and would later repeat them to García-Pineda. The artist realised that her grandmother was suffering from Alzheimer when she started misplacing the sounds.

Over the course of the short animated short film, García-Pineda draws a symbolic map that goes through time and geography to evoke the quiet violence of political repression, forced migration and class issues. The narration also suggests small acts of resistance, such as the grand-mother’s refusal to chose a second name to replace the one she had been given by her family or the nanny telling children stories in Catalan, at a time when Franco’s language policies had excluded languages other than Spanish from public events and spaces.

García-Pineda’s drawing reconstructs a history of which there are almost no images and of which not all perspectives have been preserved, weaving together personal and collective histories to reflect on the strategies to reconstruct the memory of what has been erased.

The title of the work alludes to the forgetting curve hypothesis of the decline of memory retention in time. This curve shows how information is lost over time when there is no attempt to retain it. It also evokes the Pact of Forgetting (el Pacto del Olvido) which guaranteed impunity for all those who participated in pro-Francoist crimes during the Civil War and the dictatorship.

Fernando Sánchez Castillo, Lona del memorial en homenaje a los 2.936 fusilados por el franquismo entre 1939 y 1945, 2019

In 2018, Fernando Sánchez Castillo was commissioned to create a memorial honoring 2,936 individuals executed by Franco’s supporters after the Spanish Civil War and are buried at Cementerio del Este, in Madrid. During Franco’s regime, and for many years afterwards, these individuals were neither acknowledged as victims of political assassination nor celebrated as fighters for democracy. Recognition only came in 2007, with the passing of the Ley de Memoria Democrática (Law of Democratic Memory) which formally condemned the human rights abuses of the Franco regime and gave certain rights to the victims and the descendants of victims of the Civil War and the subsequent dictatorship.

A year after the commission, the newly-elected right-wing Madrid city council decided to remove the names of the 2,936 deaths commemorated by the monument. They were replaced with a vague recognition of all deaths by violence between 1936 and 1944, including those killed by the Republicans. For the families of the executed, this was a second erasure, a cruel denial of their right to inscribe their loved ones’ names on their grave.

Fernando Sánchez Castillo’s artwork in Ghent presents the remnants of the original monument: a photograph of the memorial plaques stored in a municipal depot and the list of the names of the people killed by the fascists. The artist donated the original banner featuring the list of names to Memoria y Libertad, an association for the relatives of those killed under Franco’s regime.

Sánchez Castillo’s work not only rescued the names, it also shows how their removal was a political decision that bears consequences for the families of the victims of fascism. The elimination of the names makes it clear that the right to remember the Spanish Civil War and the Franco regime continues to polarise political parties and society.

Fernando Sánchez Castillo, La arquitectura para el caballo, 2002

Fernando Sánchez Castillo, La arquitectura para el caballo, 2002

A horseman is riding through classrooms, hallways and corridors of the Faculty of Philosophy at the Autonomous University of Madrid. With La arquitectura para el caballo (Architecture for the Horse), Sánchez Castillo exposes the sinister intent behind the campus’s design, conceived in the final years of Franco’s regime. The buildings were engineered to allow riot police to enter everywhere, even on horseback, and easily quash any student rebellion. Furthermore, the site was deliberately chosen outside the city, in a valley that could be isolated and surrounded by military posts. The campus was designed with the same specifications. It has no gathering places; only corridors and access points tailored for security forces.

Canicas (Marbles), another of Sánchez Castillo’s videos, shows how imaginative tactic can render useless an architecture designed to control human behaviour. Forming a diptych with the previous work, Canicas recalls how students outmaneuvered Franco’s mounted police by scattering marbles across the floor, preventing both the animals and the authorities from entering the university spaces. Tiny toys are able to paralyse sophisticated machines of repression.

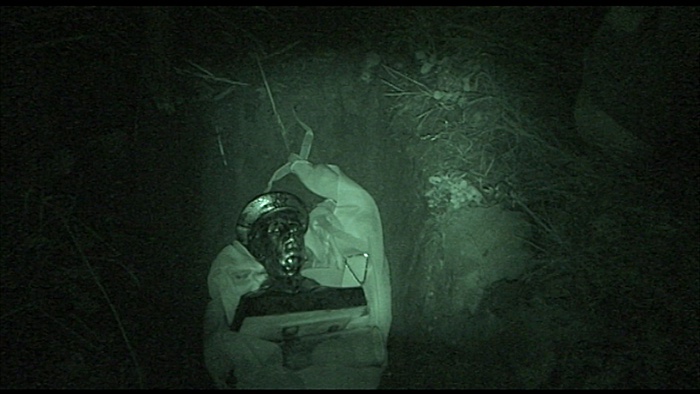

Núria Güell, Resurrección (film still), 2013

Núria Güell, Resurrección, 2013

The National Francisco Franco Foundation (FNFF) was created in 1975 to “disseminate and promote the study of the life, thought, legacy and work” of the authoritarian figure. As well as holding a library of more than 30,000 documents at its headquarters in Madrid, the private foundation sells books and a selection of patriotic braces, playing cards, cufflinks and hoodies on its website. Until 2004, the FNFF enjoyed public funding. That year, the Spanish Ministry of Culture started proceedings to outlaw the foundation for its failure to comply with legislation that forbids any attempt to glorify the Franco regime.

In 2013, Núria Güell founded an association too. She named it after Catalan resistance fighters murdered by Franco’s troops. She then applied for a credit card for the association and used it to buy propaganda merchandise from the Franco Foundation website. Exploiting PayPal’s withdrawal period, she cancelled the transaction after the products had been delivered. The Foundation never got its money. The artist shared the trick with political activist groups so they could repeat it for their own purposes.

Güell buried the purchased objects on the side of a road, in reference to the mass graves where thousands of victims of fascism lie. There are an estimated 6,000 unmarked mass graves dotted around the country, in ravines, wells, woodlands, gardens, cemeteries, side roads and remote hillsides. In the half-century since Franco’s demise, exhumations have been slow, hindered by logistical, financial and legal challenges.

The work denounces the scandal of the existence, in a democratic country, of a foundation whose purpose is to glorify the work and memory of a dictator.

Joan Rabascall, Spain is different (from the series Spain is different), 1977

Joan Rabascall explored the evolution of the content and design of tourist postcards in Spain during the economic “opening” of the dictatorship, when the tourism industry played an important role in helping the country shift from autarky to a market-driven economy. Based around ‘Spain is different’, the slogan chosen by the Ministry of Tourism to attract mass tourism to the sunny beaches of Spain, the series highlights the contrast between the idea of opening up the country through tourism, and the actual situation of the country at the time.

Fernando Sánchez Castillo, Pussy Riot, 2021. From the series The Global Museum of Civil Protest (photo: Galeria Albarran Bourdais)

Fernando Sánchez Castillo, The Global Museum of Civil Protest (installation view), 2015-2022

Fernando Sánchez Castillo, Mickey Venezuela, 2021. From the series The Global Museum of Civil Protest (photo: Galeria Albarran Bourdais)

With The Global Museum of Civil Protest, Fernando Sánchez Castillo pays tribute to the inventiveness and courage of people around the world who take to the streets in protest of non democratic regimes. Demonstrators sometimes wear masks that give them both anonymity and visibility, deliberately choosing humorous or striking designs to catch the attention of the media and ensure wider dissemination. This ‘archive of resistance’ shows how protesters consciously employ the power of images as a means of exerting political pressure.

Installation view ‘Resistance. The Power of the Image, exhibition view. Photo: We Document Art. Courtesy of S.M.A.K.

Installation view ‘Resistance. The Power of the Image, exhibition view. Photo: We Document Art. Courtesy of S.M.A.K.

Installation view ‘Resistance. The Power of the Image, exhibition view. Photo: We Document Art. Courtesy of S.M.A.K.

Installation view ‘Resistance. The Power of the Image, exhibition view. Photo: We Document Art. Courtesy of S.M.A.K.

EUROPALIA ESPAÑA | Resistance. The Power of the Image was commissioned by EUROPALIA ESPAÑA and is curated by Spanish independent curator Marta Ramos-Yzquierdo and Sam Steverlynck, curator at S.M.A.K.