The Biennale de l’Image Possible/BIP, an artistic cultural biennial based in Liège, questions the nature of today’s images and our relationship with them. The theme of the last edition was transformations. Its subtitle was MUTANTX and its scope was fiercely ambitious: the porosity of genders, the tensions between natural and artificial, the confusion between real and virtual, climate anxieties, transhumanism, the transformation of everything older generations used to take for granted. It pictured the world entering unchartered, unruly but often exciting territories.

Andrea Graziosi, from the series ANIMAS

Eva L’Hoest, Firebird (film still), 2023

BIP – Former library Les Chiroux. Venue

This year, the biennial took place inside a massive, decrepit labyrinth: Les Chiroux, Liège’s former provincial library. A glass and concrete monster that was considered “state of the art” when it opened in 1971, the construction has been abandoned for a fancier location. I don’t know what will happen to the former library, but its 7,000 m2 of now empty reading rooms, offices, corridors and storerooms were a fabulous venue for the photos, videos, films and installations of the biennale. I wish i could have visited the biennale a second time. Or a third time. There was so much to see, and most of it deserved far more time and mental space than i had. Here’s a quick selection of the works i found particularly interesting:

Toma Gerzha. Installation view. Photo: BIP 2024

Toma Gerzha, Nikita’s car (Image created using AI)

Toma Gerzha, Zheka and Fira (Image created using AI)

Toma Gerzha, .ru (Image created using AI)

Toma Gerzha grew up in Russia and has lived in the Netherlands since 2009. Her documentary photo series CTRL+R portrays Gen Z people, the first generation raised in a post-Soviet society and a digital environment.

The invasion of Ukraine interrupted Gerzha’s work and she returned to the Netherlands. Realising that she could not fly back to Russia, Ukraine and Belarus to finish her work, she decided to use Midjourney to continue the project from a distance using the photos she had already taken. In the new series .ru, the main characters are still the same, but they appear in settings and activities that belong to different places and times. The generative artificial intelligence program added a layer of weirdness and a thicker layer of Western (and slightly degrading) clichés about post-Soviet culture.

The idea that AI can help you follow your friends from afar but with an added element of eeriness is, I think, very moving. It might seem unrequired in these days of constant connectivity but the photos are probably no less authentic than the ones you see on your contacts’ ultra curated Instagram feeds.

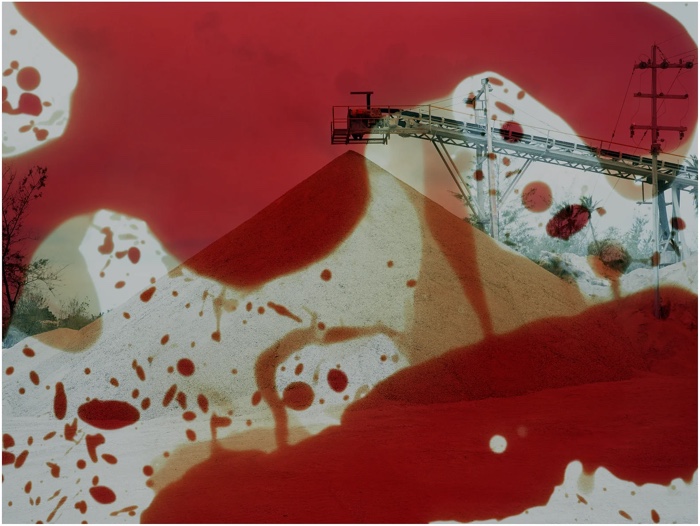

Richard Pak, Topside #01, from the series L’île naufragée, 2022-2023

Richard Pak, Topside (#1387_01), from the series L’île naufragée, 2022-2023

Richard Pak, from the series L’île naufragée, 2022-2023

Richard Pak, from the series L’île naufragée, 2022-2023

Richard Pak, from the series L’île naufragée, 2022-2023

Richard Pak, from the series L’île naufragée, 2022-2023

In less than 20 years, Nauru went from being the richest country to one of the poorest in the world. And from a paradise island to a symbol of extensive ecological degradation.

When foreign prospectors discovered that 80 percent of the island was rich in phosphate of lime, they mined the island to help meet growing demand for agricultural fertilisers. The birds, almond trees and all the biodiversity soon disappeared from the Topside. Corrupt and incompetent governments did the rest: they squandered the island’s wealth and the nation became a textbook example of resource curse. In the mid-90s, when the viable deposits of phosphate ran out, the small country sank into poverty.

In L’Île Naufragée, Richard Pak photographed the ecological, social and economic disaster that mining left behind. Some of his images show the dichotomy of the Nauruan landscape with, on one side, the lagoon with turquoise water and the palm trees that surround the Island and, on the other, just behind these few remaining trees, views of desolation. He then subjected the negatives to a chemical treatment based on phosphoric acid (H3PO4). The process alters the emulsion, sparing only the red range, making emerge landscapes sacrificed by phosphate.

At the moment, the island’s main industry comes courtesy of Australia’s offshore detention program. Since 2013, when Nauru’s notoriously bleak detention and processing centre reopened, Australia has been contributing to Nauru’s GDP by way of direct aid, visa fees and payments to the government for hosting the refugees.

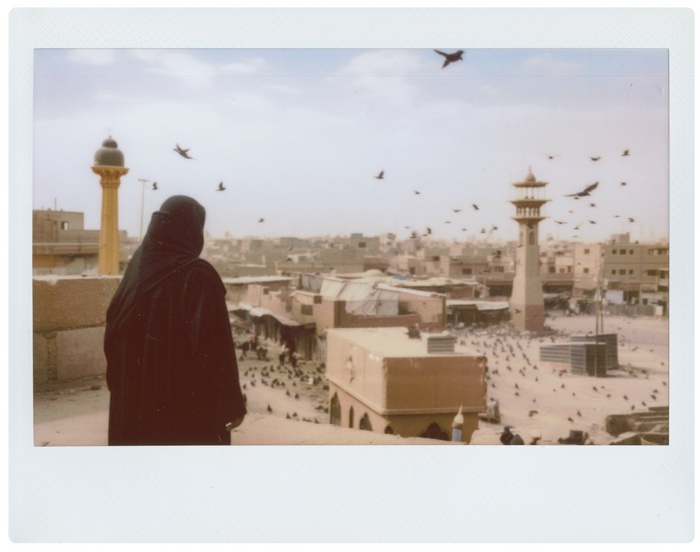

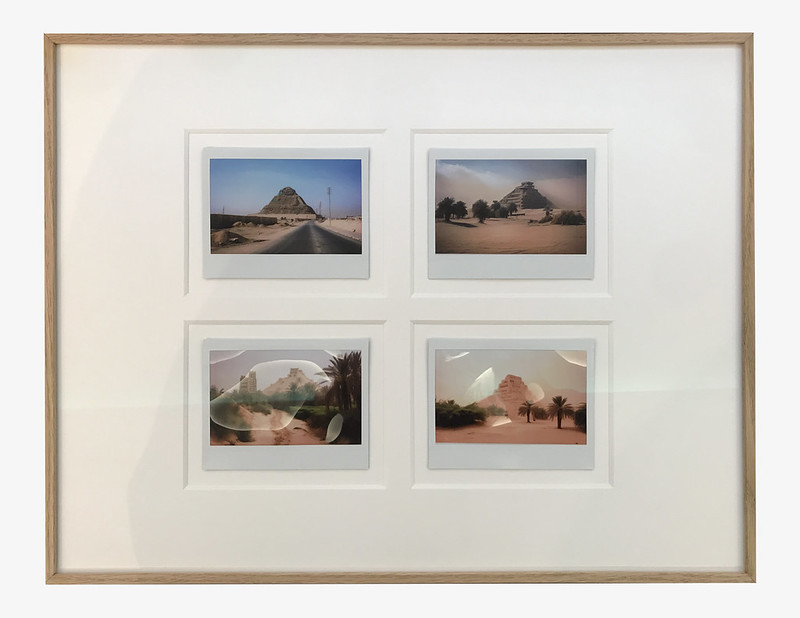

Louis-Cyprien Rials, Tasawuriy

Louis-Cyprien Rials, Tasawuriy XV – The ruins of Uzuruk – أثار ازوروك, 2023 – Leo Marin

Louis-Cyprien Rials, Babel, 2023

Tasawuriy is a series of Polaroids that documents a Middle Eastern country, its history, traditions and geography. A Polaroid is spontaneous and unique. No one questions its authenticity. Yet, the scenes that Louis-Cyprien Rials’s polaroids portray were produced using Midjourney. The country is entirely fictional. Tasawuriy, in Arabic, suggests imagination and formation of ideas. Louis-Cyprien Rials created a fictitious republic to address real problems that a country like Iraq is experiencing: the legacy of Western interventions, the status of women, the poor air quality, the catastrophic impacts of U.S. bombings on the environment, the political tensions, etc.

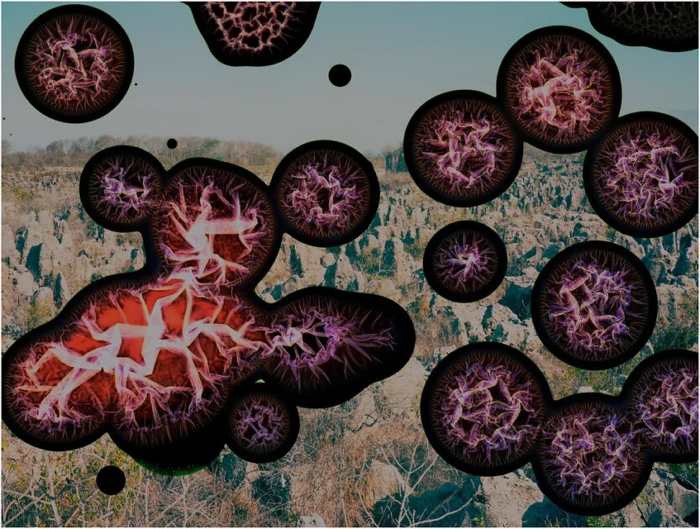

Abdessamad El Montassir, Al Amakine, 2016-2020

Abdessamad El Montassir. Installation view. Photo: BIP 2024

Abdessamad El Montassir, Al Amakine, 2016-2020

“Everything we’ve been through, we cannot say. Interrogate the ruins, interrogate the desert and the thorny plants. They’ve seen everything, they’ve lived through everything and they stayed put. As for us, we no longer have the words.” These are the words of Khadija, who left her nomadic life for the city in 1975. With Al Amakine (al’amakin means “places, locations” in Arabic), Abdessamad El Montassir takes stock of the political, cultural and social stories inherent in the Sahara of Southern Morocco that have been orally transmitted by the local population. These narratives, however, have been invisibilised, or voluntarily denied by official discourses. The artist thus opened up to the memories of non-human elements –the plants, wind, sand, rocks, landscapes– that make the South-Western Sahara in Morocco alive. By giving visibility to their resilience, poetry and testimonies, El Montassir wants to make emerge the narratives and non-human traumas of the contested desert. These testimonies reveal political, cultural and social events that took place in this geographical area but that were cast aside by the official historical discourse.

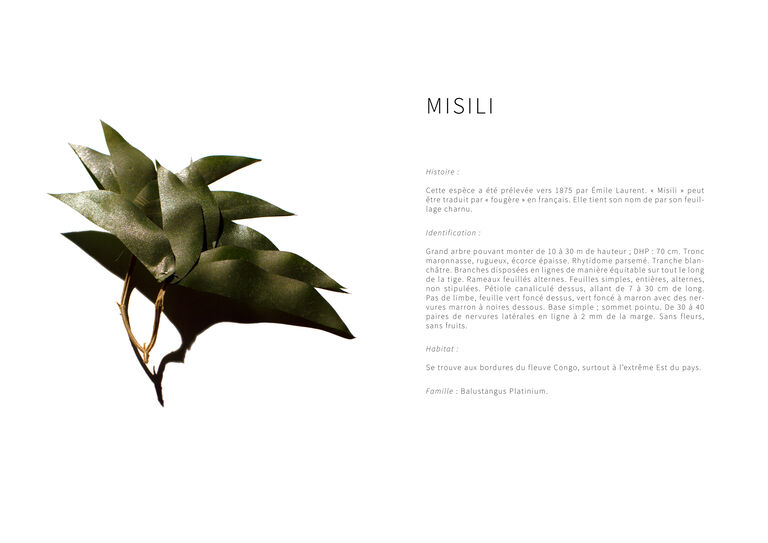

Anna Safiatou Touré, Herbier du département congolais des Serres Royales de Laeken, 2019-2020

Anna Safiatou Touré, Herbier du département congolais des Serres Royales de Laeken, 2019-2020

When Anna Safiatou Touré learnt that the plants brought back more than a century ago from the Congolese colony to Brussels for the Royal Greenhouses of Laeken did not withstand Belgium’s climatic conditions, she created a herbarium from scratch. She invented a name, a form, a descriptive sheet for each fictitious plant that would be part of the collection of herbariums of the Congolese department of the Royal Greenhouses in Laeken. Every plant carries a story that conveys an uprooting and a disappearance. In the absence of a collective narrative addressing the Belgian-Congolese colonial past, Anna Safiatou Touré opens up new narratives that mix history and plausible fiction.

Commissioned by the infamous King Leopold II, the Laeken greenhouses host one of the world’s largest collections of exotic plants. They still belong to the Belgian royal family and are accessible to the public only a few days a year.

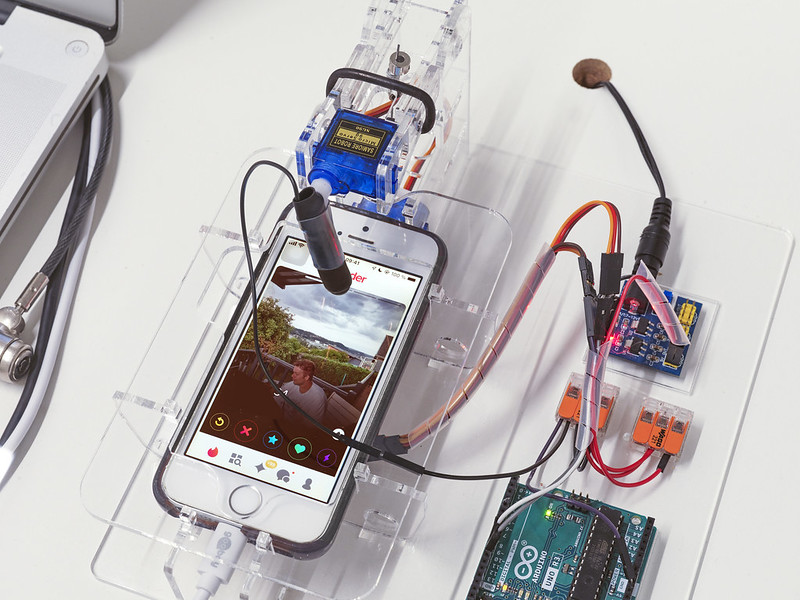

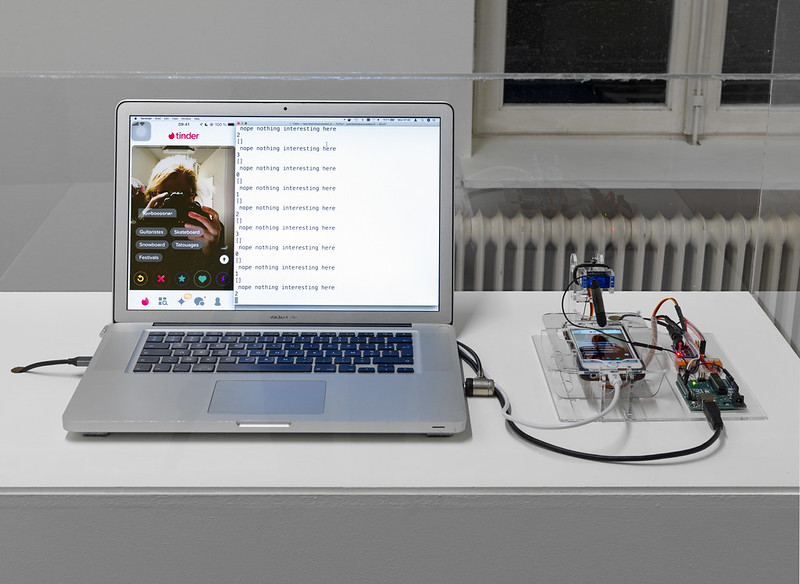

Loïs Soleil, Tinder Gun Boys, detail, 2022. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooijtif

Loïs Soleil, Tinder Gun Boys, detail, 2022. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooijtif

Loïs Soleil, Tinder Gun Boys (detail from the installation), 2022

Loïs Soleil, Tinder Gun Boys, detail, 2022. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooijtif

In her work, Loïs Soleil confronts the everyday sexist structures of the web, from its biassed algorithms to its macho subcultures. Tinder Gun Boys was born from the artist’s discovery that Tinder is full of photos of heterosexual men proudly posing with guns. She developed a robot that swiped for her on Tinder and an algorithm that spots weapons. Over time, Soleil collected hundreds of screenshots of those wannabe alpha males. She then printed the photos on tatami mats that were used during feminist self-defence classes.

More images from the BIP exhibition:

Thomas Garnier, Chimera, 2024

Thomas Garnier. Installation view. Photo: BIP 2024

Chloé Clément, Bétula, 2021

Andrea Graziosi, from the series ANIMAS

Akasha Rabut, Caramel Curves, 2012-2018

Max Blotas, Détail d’une capsule temporelle. Installation view at the exhibition Protean Fluid at Gossamer Fog, London, 2021. Photo: Dexter Lander

Agnieszka Sejud, HOAX, 2016-2020

Also part of BIP/Biennale de l’Image Possible: When forbidden flowers escape from the lab and War as a consumer good.