Hikikomori is a form of extreme social withdrawal that has become a serious problem in many countries. Hikikomori individuals isolate themselves in their room for very long periods of time. Away from school, work, family and the rest of society. In Japan alone, an estimated 1.2 million people have adapted this lifestyle, more than half of whom are 40 years or older. The phenomenon can also be observed in other parts of Asia and in Europe.

Atsushi Watanabe, I’m Here Project. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

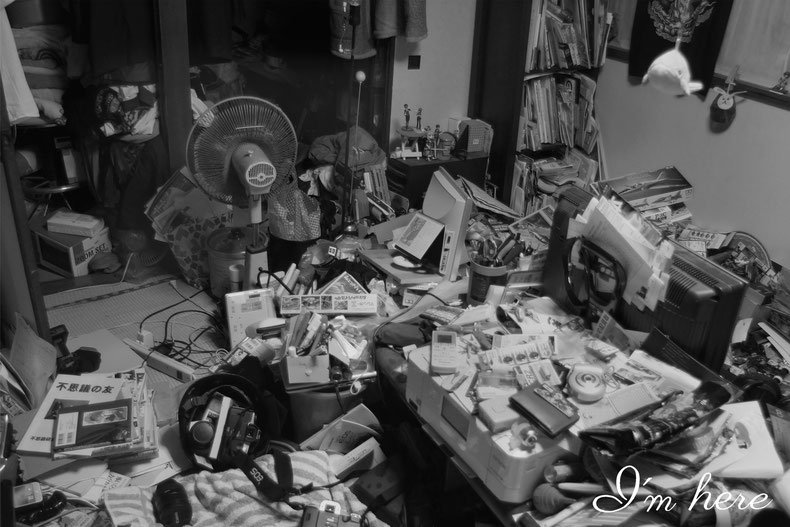

Atsushi Watanabe, I’m Here Project (photo)

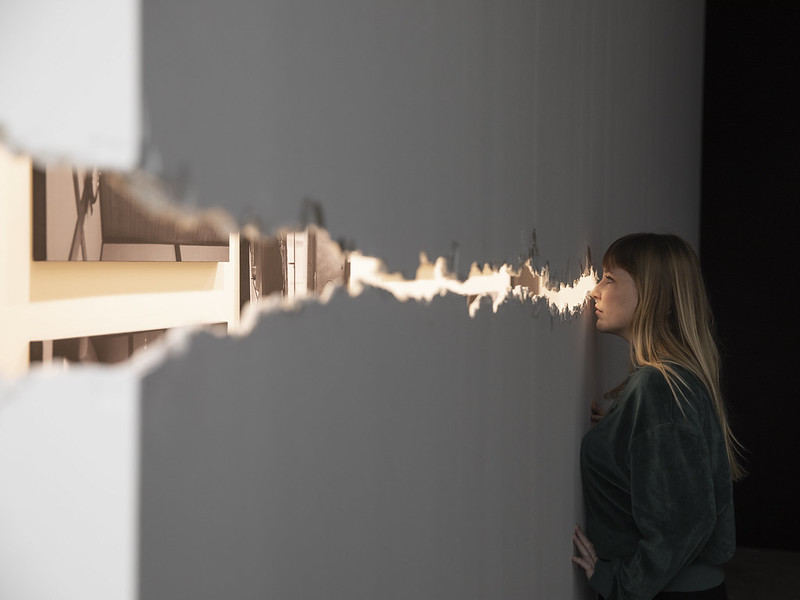

Atsushi Watanabe, I’m Here Project. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Artist Atsushi Watanabe spent 3 years as a hikikomori. He wrote that during the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake, as he was still avoiding human contacts, “many determined hikikomori were washed away along with their homes. On the other hand, some reportedly got out of their rooms because of the earthquake.”

When he later decided to stop living as a recluse, Watanabe shot a self-portrait and the state of his room. These photos were for him the first step towards social reintegration.

In the winter of 2014, he contacted hikikomori through forums and asked them to take photos of their living space. The fact that many accepted to send images of their rooms suggests that even though they’ve pulled out of society, these individuals still crave a connection with other people. Some of them actually went to the opening of Watanabe’s photo exhibition.

In I’m Here Project, the visitor can look at these photos through a crack in the wall. The personal space of the hikikomori is somehow preserved by the wall and the impossibility to even touch the photos. As for viewers, their curiosity puts them in the role of the voyeur. A compassionate, concerned fellow human perhaps, but a voyeur nevertheless.

Ief Spincemaille, Kiss Me, 2020. Photo by Veerle Scheppers and Ief Spincemaille

Karolina Halatek, Valley, 2017. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Atsushi Watanabe’s is one of the many poignant stories i encountered last week at the Artefact festival in Leuven. Open until early March at STUK House for Dance, Image and Sound and in various locations across the city, the festival explores how lonely we can feel in contemporary society. No matter how many people surround us.

By focusing on solitude, loneliness and connection in society, Artefact continued its tradition of investigating complex and urgent themes under the lens of contemporary art practices. In 2018, Artefact looked at Rare Earth. The 2017 edition was dedicated to magic. Last year’s looked at movement. 2016 was all about our relationship to the airspace.

This Winter, the festival thus brings the spotlight on the difficult subject matter of loneliness and the inability to communicate today:

What does contemporary solitude mean? How does it relate to feelings of loneliness? Can we consider loneliness not in individual terms, but as the result of more structural forces, be they social, cultural, economic, technological or architectural in nature? How do we connect in today’s society? What is the quality of our interactions / connection, and which role do (social and communication) technologies play in this?

Loneliness is an overlooked issue that might well end up defining our times. People -both young and old- living in rich countries seems to be particularly affected by a problem that is not only emotionally draining but that can also lead to psychiatric disorders and even physical health problems.

The artworks exhibited in Leuven explore some of these problems but they also consider possible ways to connect and reach out to our fellow human beings.

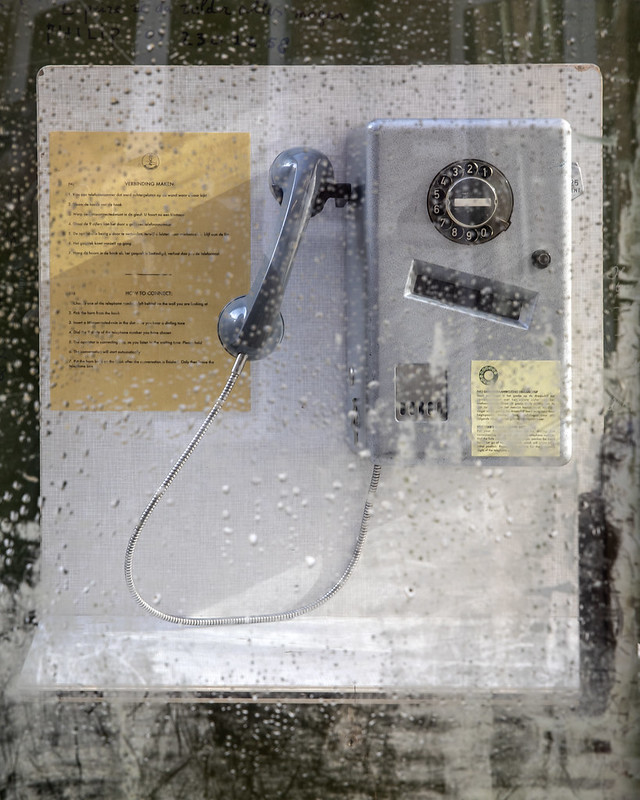

Kyoko Scholiers, Misconnected. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Kyoko Scholiers, Misconnected. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Kyoko Scholiers, Misconnected. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Kyoko Scholiers, Misconnected (trailer)

Kyoko Scholiers used an almost obsolete technology to reach out to men, women and children in Belgium who are somehow disconnected from society. The phone callers she talked to were prisoners, refugees, vagrants and homeless people, but also prostitutes, patients or just people who ran out of luck, youngsters growing up in the absence of their parents, (ex) cult members, hermits, monks, etc.

Scholiers edited the recordings of these conversations in five-minute sound excerpts, to be listened to in an installation of telephone boxes. Phone numbers are written and carved on the wall. When you dial one of them, you hear the voice of an unknown, companionless caller.

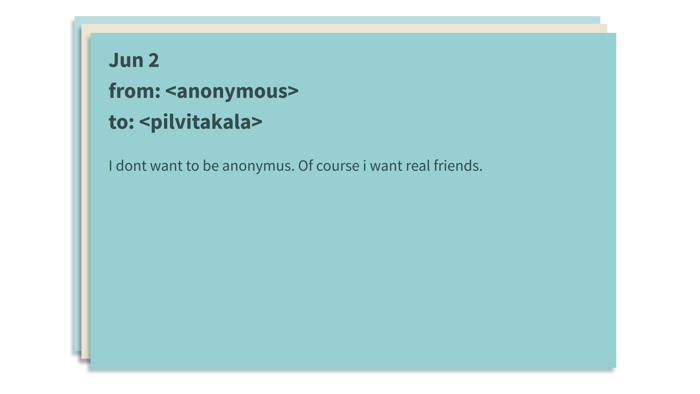

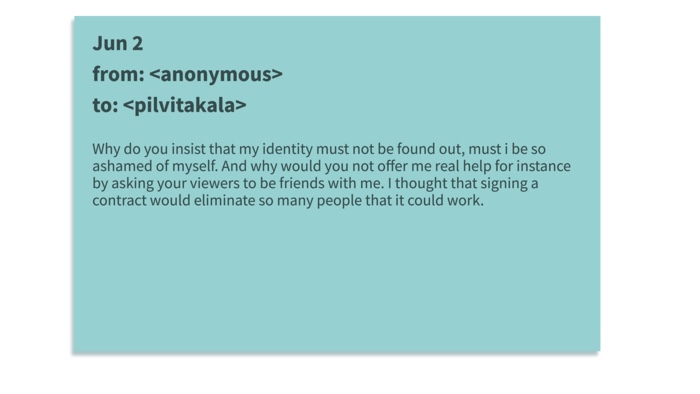

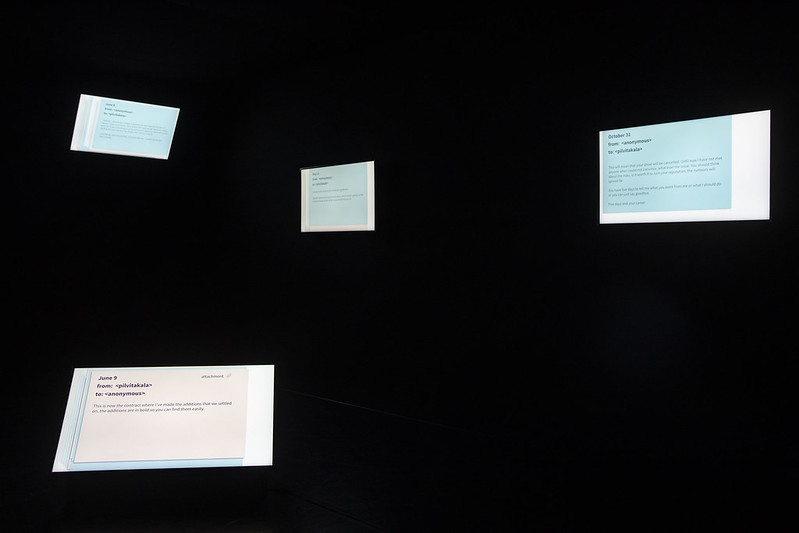

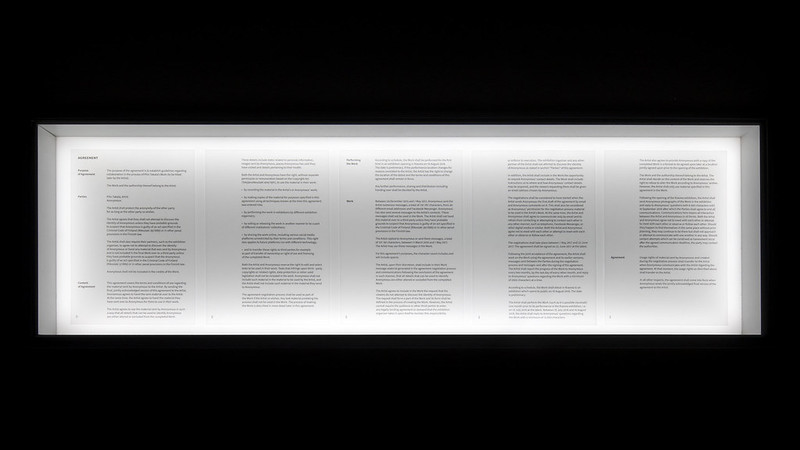

Pilvi Takala, Admirer, 2018

Pilvi Takala, Admirer, 2018

Pilvi Takala, Admirer, 2018. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Pilvi Takala, Admirer, 2018. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Pilvi Takala, Admirer, 2018

Pilvi Takala is the kind of artist whose talent and audacity keep amazing me. I love her kind, gentle way to provoke reactions and thinking. In 2006, she spent a week in a Berlin shopping mall, carrying a lot of cash in a transparent plastic bag. In 2009, she dressed up as Snow White and went to Euro Disney near Paris. As she walked towards the ticket entrance, children stopped her and asked for autographs and photos. Guards also stopped her to say that she couldn’t get access to the theme park dressed like that.

The work she is showing at Artefact is Admirer, the follow-up of a previous artwork that offered a free text-messaging service for anyone who wanted to have an anonymous, personal conversation with someone who would always reply. One of the people who engaged with the service took the offer very seriously and quickly became aggressive, demanding and invasive.

The artist then decided to negotiate with this Anonymous correspondent a contract that defined precisely the terms of their communication and defined the boundaries of their interaction. The collaborative process, done over email exchanges, lasted for two months. The elaboration of the contract was both, for the artist, a form of emotional labour and an attempt at self-preservation.

Lauren McCarthy and Kyle McDonald, Pplkpr

The Pplkpr app, by Lauren McCarthy and Kyle McDonald, tracks, analyzes and auto-manages relationships. A smartwatch equipped with a GPS and a heart rate monitor follows your physical and emotional response to the people around you. Based on the data gathered, machine learning helps you determine who should be “auto-scheduled” into your life and who should be erased.

Pplkpr questions how far the quantified living can be applied in our life. How would its adoption in our social and emotional life influence the people we hang around with and the kind of relationships we have with them? Posing as a startup (and doing a painfully credible job at it), the work critiques the techno-solutionism of startup culture.

Mehtap Baydu, Cocoon, 2015

Mehtap Baydu, Cocoon, 2015. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Mehtap Baydu asked men around her to take pictures of themselves and give her their shirts. Some were friends and colleagues. Other mere acquaintances. Their shirts were then cuts in strips and winded into yarn. One ball of yarn = one man. Then she literally knitted herself inside the cocoon.

Meiro Koizumi, Theatre Dreams of a Beautiful Afternoon, 2010-2014. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Meiro Koizumi, Theatre Dreams of a Beautiful Afternoon, 2010-2014

Meiro Koizumi asked an actor to show distress and cry on a train going through Tokyo. Koizumi notes: “When he was just sobbing, people didn’t respond to him at all. So I asked him to perform again and again. At the eighth take, when I asked him to just scream at the top of his voice, we finally managed to shatter people’s mask. During the production, the earthquake struck, and nuclear plants exploded in north-eastern Japan. It was really a time in which everybody in Tokyo felt anxiety from the fear and uncertainty of the condition at the nuclear plant. We all wished it were a dream.”

The man’s display of emotions clearly violated the boundaries between the private and the public, what you should keep home and what you’re allowed to share with society. It also shows how lonely you can be in a crowd.

Other works and photos from the exhibition:

Chloé Op de Beeck, Composition for Flora, Objects and Bodies, 2020

Atsushi Watanabe, Suspended Room, Activated House of 1:10 Scale. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Liana Finck. Opening night of Artefact 2020 : Alone Together. Photo by Joeri Thiry

Molly Soda. Opening night of Artefact 2020 : Alone Together. Photo by Joeri Thiry

Molly Soda. Opening night of Artefact 2020 : Alone Together. Photo by Joeri Thiry

Molly Soda. Opening night of Artefact 2020 : Alone Together. Photo by Joeri Thiry

Hanne Lippard. Opening night of Artefact 2020 : Alone Together. Photo by Joeri Thiry

Karolina Halatek. Opening night of Artefact 2020 : Alone Together. Photo by Joeri Thiry

Cécile B. Evans, Amos’ World – Episode 3. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Cécile B. Evans, Amos’ World: Episode Three, 2018 (video still)

Molly Soda. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

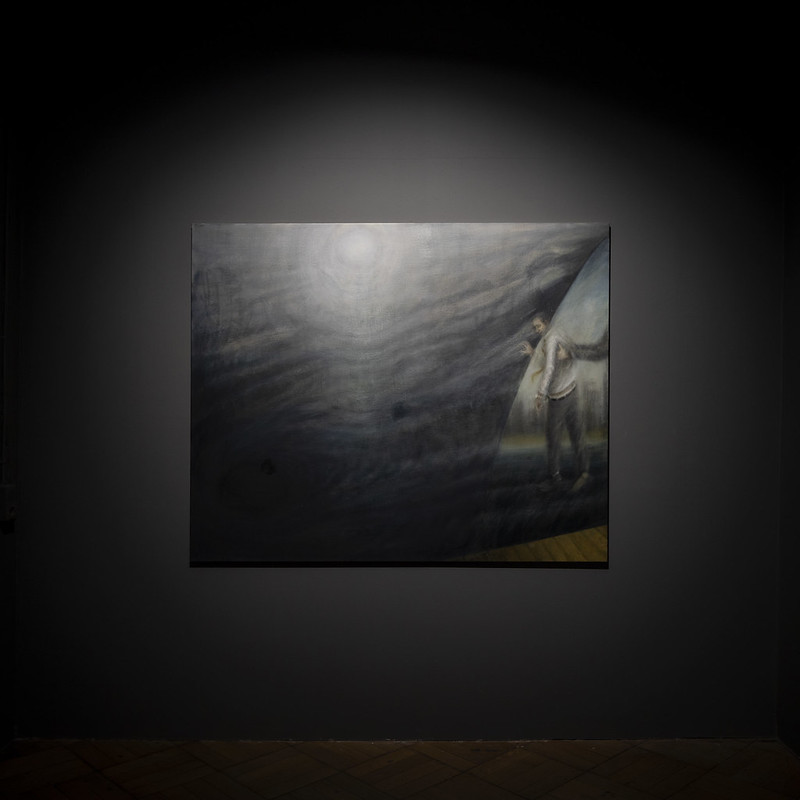

Helmut Stallaerts, The Dissolvement. Installation view at STUK. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Ante Timmermans. Opening night of Artefact 2020 : Alone Together. Photo by Joeri Thiry

Artefact 2020: Alone Together remains open in STUK, Leuven until 1 March 2020. Entrance to the exhibition is free. Check the accompanying programme of a series of films, lectures, workshops and concerts.